Crab

CRAB, a name applied to the Crustacea of the section Brachyura of the order Decapoda, and to other forms, especially of the section Anomura, which resemble them in appearance and habits.

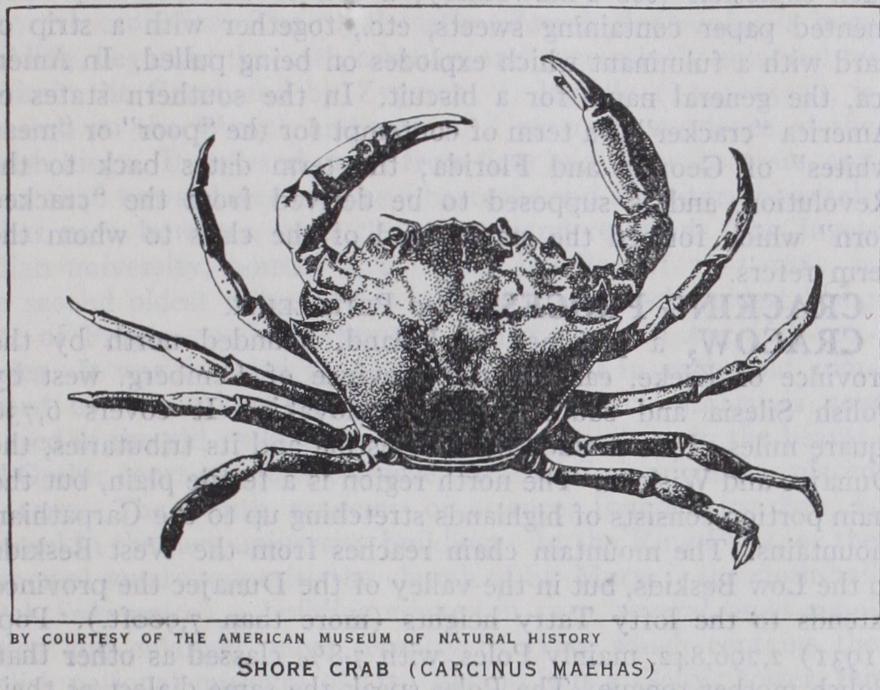

Brachyura, or true crabs, are distinguished from the long-tailed lobsters and shrimps by the small abdomen or tail, folded up under the body. In most the body is transversely oval or tri angular in outline and more or less flattened, and is covered by a hard shell, the carapace. There are five pairs of legs. The first pair end in nippers or chelae and are usually much more massive than the others which are used in walking or swimming. The eyes are set on movable stalks and can be withdrawn into sockets in the front part of the carapace. There are six pairs of jaws and foot-jaws (maxillipedes) enclosed within a "buccal cavern," the opening of which is covered by the broad and flattened third pair of foot-jaws. The abdomen is usually narrow and triangular in the males, but in the females it is broad and rounded and bears appendages to which the eggs are attached after spawning.

As in most Crustacea, the young of nearly all crabs, when newly hatched, are very different from their parents. The first larval stage, known as a Zoea, is a minute transparent organism, swim ming at the surface of the sea. It has a rounded body, armed with long spines, and a long segmented tail. The eyes are not stalked, the legs not yet developed, and the foot-jaws form swimming paddles. After casting its skin several times as it grows in size, the young crab passes into a stage known as the Megalopa, in which the body and limbs are more crab-like, but the abdomen is large and not folded up. After a further moult the animal assumes a form very similar to that of the adult. There are a few crabs, especially those living in fresh water, which do not pass through a metamorphosis but leave the egg as miniature adults.

Most crabs live in the sea, and even the land-crabs, which are abundant in tropical countries, visit the sea occasionally and pass through their early stages in it. The river-crab of southern Europe or Lenten crab (Potamon edule, better known as Thelphusa fluviatilis) is an example of the fresh-water crabs which are abundant in most of the warmer regions of the world. As a rule, crabs breathe by gills, which are lodged in a pair of cavities at the sides of the carapace, but in the true land-crabs the cavities become enlarged and modified so as to act as lungs for breathing air.

Walking or crawling is the usual mode of locomotion, and the peculiar sidelong gait familiar to most people in the common shore-crab, is characteristic of most members of the group. The crabs of the family Portunidae, and some others, swim with great dexterity by means of their flattened paddle-shaped feet.

Like many other Crustacea, crabs are often omnivorous and act as scavengers, but many are predatory in their habits and some are content with a vegetable diet.

Though no crab, perhaps, is truly parasitic, some live in rela tions of "commensalism" with other animals. The best known examples of this are the little "mussel-crabs" (Pinnotheridae) which live within the shells of mussels and other bivalve mollusca and share the food of their hosts. Many of the sluggish spider crabs (Maiidae) have their shells covered by a forest of growing seaweeds, zoophytes and sponges, which are "planted" there by the crab itself, and which afford it a very effective disguise.

Many of the larger crabs are sought for as food by man. The most important and valuable are the edible crab of British and European coasts (Cancer pagurus) and the blue crab of the Atlantic coast of the United States (Callinectes sapidus).

Among the Anomura, the best known are the hermit-crabs, which live in the empty shells of Gasteropod Mollusca, which they carry about with them as portable dwellings. In these, the abdomen is soft-skinned and spirally twisted so as to fit into the shells which they inhabit. As the crab grows it changes its dwell ing from time to time, often having to fight with its fellows for the possession of an empty shell. Sometimes an annelid worm lives inside the shell along with the hermit and often the outside is covered with zoophytes. In some species, sea-anemones are constantly found attached to the shell, profiting by the active locomotion of the crab and probably sharing the crumbs of its food, while affording their host protection by their stinging powers.

In tropical countries the hermit-crabs of the family Coenobit idae live on land, often at considerable distances from the sea, to which, however, they return for the purpose of hatching out their spawn. The large robber-crab or coconut crab of the Indo Pacific islands (Birgus latro), which belongs to this family, has given up the habit of carrying a portable dwelling, and the upper surface of its abdomen has become covered by shelly plates. It climbs palm trees to get the fruit. (W. T. C.) the name given in North America to several native trees of the apple genus (Pyres or Malus). In general they resemble the cultivated apple, especially in flowers and foliage, but have more slender trunks, stiffer and more or less spiny branches, and much smaller, usually very acid fruit. The best known is the American crab-apple (P. coronaria or M. coronaria), called also fragrant crab-apple and garland crab, which is one of the most beautiful of North American trees, when in blossom in April or May, some varieties being very attractive when culti vated as ornamentals. It has exceedingly fragrant rose-red flowers, II. in. to 2 in. across, and delicately scented but very acid fruit, I in. to i ? in. in diameter. The tree grows to a height of 25 ft., with a trunk r ft. in diameter, in open woods and thickets from western New York and southern Ontario to Wisconsin and south ward to North Carolina and Missouri. Other noteworthy species are the narrow-leaved crab-apple or southern crab (P. angustifolia or M. angustifolia), smaller than the foregoing, with narrowly oblong leaves and yellow-green fruit, a in. to i in. in diameter, native to thickets from southern Virginia to southern Illinois and southward to Florida and Louisiana; the prairie crab-apple (P. iowensis or M. iowensis), with the leaves white-woolly beneath, white or rose-tinted flowers, r in. to 2 in. across, the dull greenish yellow fruit, I 4 in. to II in. in diameter, growing of ten in pure thickets on prairies from Wisconsin and Minnesota southward to Kentucky and Louisiana; and the Oregon crab-apple (P. rivularis or M. rivularis), the largest species, with a trunk sometimes 3o f t. to 4o ft. high and I f t. to i 2 ft. in diameter, with white flowers in. across and yellowish to reddish fruit, about 2 in. diameter, found along streams near the Pacific coast from California to Alaska. By many authorities the sparingly cultivated Soulard crab (P. Soulardii or M. Soulardii) with more or less edible fruit, is a natural hybrid between the prairie crab-apple and the apple. Although the native crab-apples of the eastern States are used to some extent in making jellies and when baked are sparingly eaten, the fruit is of little economic importance.