Cretaceous System

CRETACEOUS SYSTEM, the group of rocks which nor mally occupy a position above the Jurassic System and below the Tertiary. In many areas, the system (from Lat. creta, white chalk, a characteristic rock-type of the Upper Cretaceous in N.W. Europe), falls naturally into two divisions; the lower is sometimes regarded as a separate system (the Comanchean) in North America, where the unconformity between the two di visions is well-marked. The names of the stages and some of the zones, as generally accepted in England, are given in Table I. which shows also the position in the system of the more im portant strata in the British Isles. Table II., with Table III. for N. America, gives the stages and substages, and an approximate correlation of the better known Cretaceous strata of the world; for correlation over wide areas, the Ammonoidea are (as usual in the Mesozoic) the most satisfactory group of fossils. It should be remembered that the names of the divisions of the Cretaceous given in these tables have been interpreted in widely different senses in the past, and that there is by no means general agree ment in their usage even now. The Albian is often regarded as the lowest stage of the Upper Cretaceous.

British Isles.

The Wealden beds, a thick and variable series of estuarine and fresh-water deposits, are found in the Weald, the Isle of Wight, the Isle of Purbeck and the Boulonnais. The lower beds are usually sandy, the upper argillaceous; limestones occur rarely. The Wealden passes conformably down into the Purbeck, which it closely resembles ; it is accordingly sometimes regarded as Jurassic. The fossils include fish, reptiles, plants and estuarine and freshwater Mollusca ; and the Wealden was evidently _de posited in a lagoon or estuary which probably did not extend far beyond the present limits of its outcrop. The beds of the same age found in Norfolk, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire are marine, and their fauna in part is closely allied with that of similar de posits in Russia. The Spilsby Sandstone and lower part of the Speeton Clay are often regarded as Jurassic. Between the Wealden area and Norfolk, the Neocomian is missing, and a barrier of Palaeozoic rocks (now buried under later deposits beneath Lon don) probably separated the estuarine and marine areas.The Aptian strata are everywhere marine, the Wealden area having been invaded by the sea. The Aptian is well developed in the Weald and the Isle of Wight, where it is usually argillaceous in the lower part and sandy in the upper ; the sandstones are oc casionally green through the presence of glauconite. It rests con formably on the Wealden, but thins to the westward and over laps the Wealden in Wiltshire. Between Wiltshire and Norfolk. it is represented by thin sandstones (such as the Faringdon Sponge Bed of Berkshire), resting on Jurassic beds, often with a basal conglomerate. The Snettisham Clay of Norfolk and the Tealby Limestone of Lincolnshire are sometimes considered Neocomian.

The Albian is represented by three facies or types of deposit : a blue clay with phosphatic nodules (Gault) ; a glauconitic sand stone (Upper Greensand) ; and a hard red limestone, often with small pebbles (Red Chalk). Since these three rock-types were each laid down under different conditions, their faunas are differ ent ; but ammonoids are found in each and enable a correlation to be made. The Red Chalk of Norfolk passes laterally into the Gault of Cambridgeshire; and the Gault of the east Weald passes westwards into Upper Greensand which overlaps the Aptian into Devon. The Gault rests upon the Palaeozoic ridge under London, showing that the Albian sea had submerged this barrier.

The rest of the Cretaceous is represented by the Chalk forma tion, which stretches from Flamborough Head in Yorkshire to the coast of Dorset (forming the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire Wolds and the Chilterns), encircles the Weald as the North and South Downs, underlies the Tertiary beds round London and Hampshire, and is found in north France. Where it rests upon the Gault, the lower part of the Cenomanian is an argillaceous chalk (Chalk Marl) ; where on Upper Greensand, a glauconitic sandy limestone (Chloritic Marl) ; where on Red Chalk, a pure white limestone (Chalk). In Devon, Antrim, Argyll and Mull, it is represented by glauconitic sandstones, indicating the nearness of land. In Cam bridgeshire, at the base of the Cenomanian is a glauconitic con glomerate, the Cambridge Greensand, with phosphatic nodules in part derived by erosion from the Gault. Otherwise, the Chalk formation is composed almost entirely of chalk, a white limestone with from 95% to 99% of calcium carbonate. Flints are com mon in the upper Middle Chalk of East Anglia and the north, and in the Upper Chalk throughout. Marly bands occur sparsely, and nodular beds (such as the Chalk Rock) are more common, especially in the lower Middle Chalk (Melbourn Rock) . The top of the Cretaceous is everywhere missing : the Danian may be represented by the Ostrea lunata beds of Trimingham, Norfolk. The Tertiary rests unconformably upon the Chalk. Thus in the British Isles, the invasion of the Wealden estuary or lagoon by the Aptian sea; the submergence of the Palaeozoic ridge by the Albian sea ; the thinning out of the Lower Cretaceous sediments in the south of England to the west, and to the north against the Palaeozoic ridge; the extension of the upper deposits beyond the limits of the lower into Dorset and Devon, and into Ireland and Scotland : all these facts point to a gradual encroachment of the Cretaceous sea. Igneous activity is unknown, and earth movement is gentle and relatively unimportant—such as the minor folding which led to the removal of the top of the Gault and deposition of the Cambridge Greensand in Cambridgeshire.

Relations of the Cretaceous Strata.

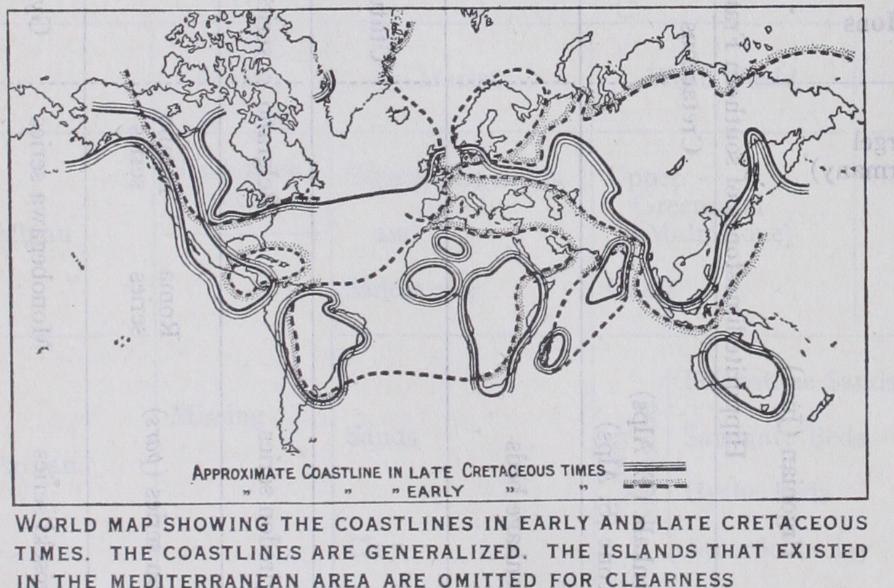

The upper and the lower limits of the Cretaceous system are often sharply defined by unconformities. Since the Cretaceous beds in many areas are transgressive over older formations, the lowest Cretaceous being missing, the lower unconformity is well marked. In the Alps and Himalayas there is sometimes an apparent continuity from Jurassic into Cretaceous marine sediments; a similar continuity in non-marine beds is seen in the south of England and north-west Germany (Wealden), and in Australia (Walloon series). The plant-bearing deposits of the Atlantic coast region of the United States (Potomac series) and Japan (Rhyoseki series) may be in part Jurassic. The lacustrine and fluviatile Laramie formation of the western interior of the United States helps to bridge the gap between the vertebrate faunas of the Cretaceous and the Eocene; the chalky limestones, of Malmo (Fennoscania) and Faxe (Den mark), in which two typical Mesozoic groups (the ammonoids and belemnites) are not found, have been regarded as Tertiary but are usually included in the Cretaceous. (Table II.) Physiographical Conditions, Earth Movements and Ig neous Activity.—Non-marine sediments are found, for the most part, either at the beginning, or, to a less extent, at the end of the period. As examples of Neocomian terrestrial, fluviatile or estuarine deposits may be cited the Wealden of England, the Boulonnais, the Franco-Belgian coalfield and Hanover; the lower part of the Uitenhage series (Enon Beds, Variegated Marls and Wood Beds) of the Cape Province of South Africa; the Potomac, Kootenay and Morrison series of the United States; the upper part of the Walloon series of Australia ; and the Rhyoseki series of Japan. The sea invaded some of these areas in Neocomian times, depositing, for instance, the upper part of the Uitenhage series (Sunday's River Beds) in Cape Province, and the Mono gebawa series (in part Albian) in Japan. In Australia, the marine Aptian (Roma series and Maryborough Beds) are in part overlapped by the marine Albian (Tambo series). In north-west Europe a similar transgression of the sea continued with minor interruptions from Aptian into Senonian times, invading the Armorican massifs in Ireland, Brittany, Spain and the Ardennes; and chalk practically free from material derived from existing land masses was laid down in the British Isles, northern France, extra-alpine Germany, south Scandinavia, Denmark and Russia. In the Tethys sea, which extended along the Mediterranean area across the site of the Himalayas, the western part of the southern margin—the north of Africa—was also invaded by the sea. In the shallow waters of the Tethys flourished the rudists, with gastero pods and reef-building corals ; a similar facies is found in Texas, Alabama, Mexico and the West Indies. The lamellibranch faunas of the sublittoral Neocomian deposits of the south Andes, south Africa and Tanganyika Territory are very similar to each other, and distinct from those of the northern hemisphere : they afford evidence for the hypothetical South Africa—Brazil Cretaceous continent. A similar Neocomian fauna is found in Cutch, Mada gascar and New Caledonia ; the southern Cretaceous land-masses are often regarded as parts of the hypothetical Permo-Carbon iferous Gondwanaland. Evidences of a marine Cenomanian trans gression are seen in Brazil and peninsular India.The unconformity between the Upper and the Lower Creta ceous of North America, and the dissimilarity in the areas of deposition, indicate important earth-movement in mid-Cretaceous times. The more wide-spread unconformity at the end of the Cretaceous and beginning of the Tertiary was due to a more general withdrawal of the sea accompanied by important de f ormative earth-movements and igneous activity. The folding and elevation of the Cordilleras and the Appalachians date in part from this period. The most important igneous activity was the formation of the Deccan traps. These basic lavas, erupted from fissures, cover 200,000 sq. miles and are from 4,00o to 6,000 feet thick.

Economic Products.

In the British Isles, local limestones of the Walden (Sussex Marble) and Hythe Beds (Kentish Rag) have been used as building stones. Fuller's earth occurs in the Sandgate Beds, and glass-sands in the Lower Greensand. More important is the manufacture of bricks and tiles from the Gault, and of lime and cement from the Chalk. The clay ironstones of the Wadhurst Clay were once the main source of the English iron supply, and more recently the phosphatic nodules of the Cam bridge Greensand have been exploited.Perhaps the most important economic product of the Cretaceous is coal. The Laramie formation, in the western interior of the United States, contains lignite and also, in places, anthracite.

Lower Cretaceous coal seams are known in Dakota, Alaska and New Zealand ; in the Senonian may be mentioned the coal bearing Urakawa series of Japan.

The Cretaceous Fauna and Flora.

The flora is best known from the United States, especially from the Potomac formation of Maryland and Virginia. That of the lower divisions (Patuxent and Arundel series) is very similar to the Upper Jurassic flora; it consists chiefly of ferns, conifers and the now extinct Bennet titales (usually grouped with the modern Cycadales), often well preserved and known in considerable detail: leaves of an angio sperm type occur very rarely. Similar floras of Lower Cretaceous age are found in the English Wealden, in Belgium and Germany, in the Uitenhage series of South Africa and the Rhyoseki series of Japan, in west Greenland and Spitzbergen. In the third division of the Potomac formation (the Patapsco series), there is a sudden development of angiosperm leaves. In the Upper Cretaceous, the angiosperms are the dominant group, replacing the Bennetti tales ; the flora is wide-spread, ranging from Alaska to Argentina and occurring in west Greenland, western Europe and Japan; many of the species are referred to modern genera, and the whole has a subtropical aspect (see PALAEOBOTANY : Mesozoic).The smaller Foraminifera such as Globigerina and Cristellaria are important, forming for instance on the average io% of the Upper Chalk in England ; of the larger, the orbitolines (Lower Cretaceous and Cenomanian) and the orbitoids (Campanian to Tertiary) have been used for correlation in deposits of the Medi terranean region. Sponges are locally abundant (Siphonia, Ventri culites) ; calcareous forms are more characteristic of shallow water deposits, such as the Faringdon Greensand (Aptian) of Berkshire (Peronidella, Barroisia, Rhaphidonema). Corals are relatively rare. The widely distributed, free-swimming crinoids, Uintacrinus and Marsupites, characterise the Santonian. • Sea urchins are especially abundant, both regular (Cidaris, Salenia, Phymosoma) and irregular (Echinocorys, Holaster and true heart urchins). The genus Micraster in the Upper Turonian and Lower Senonian of England supplies some of the best evidence of evolu tion by slow continuous change that palaeontology affords (see PALAEONTOLOGY). Brachiopods are represented chiefly by tere bratulids and rhynchonellids. Polyzoa are abundant. Lamelli branchs are important; Aucella, characteristic of the northern Lower Cretaceous, and Inoceramus, almost universal in the Upper Cretaceous, are both useful for correlation. More important as time-indices throughout the Cretaceous, to which they are con fined, are the massive, sessile, aberrant lamellibranchs, the group of rudists (Monopleura, Requienia, Toucasia, Hippurites, Radio lites and Caprina), characteristic of a shallow-water facies of the Tethys and Central America. Gastropods are common in the same facies. The ammonoids afford the best means of correlation over wide areas. As in the Jurassic, the Phylloceratidae and Lytoceratidae persist with but little change ; it has been sug gested that these thin-shelled forms, characteristic of the deeper parts of the Tethys, were the parent stocks, which, by acquisition of ornament and modification (usually simplification) of suture line, supplied successive groups of short-lived thick-shelled forms which populated surrounding areas. Characteristic genera are Spiticeras, Polyptychites, Simbirskites (Neocomian) ; Parahopli toides, Cheloniceras (Aptian) ; Leymeriella, Douvilleiceras, Hop lites, Pervinquieria (Albian) ; Schloenbachia, Acanthoceras (Ceno manian) ; Pachydiscus, Prionotropis (Turonian) ; Mortoniceras, Parapuzosia (Senonian). With these "normal" ammonites, coiled into a closed plane spiral, are found many abnormal, "uncoiled" types ; such forms occur throughout the Mesozoic, but become common only in the Cretaceous (Crioceras, Baculites, Scaphites, Turrilites). There is also in some stocks a tendency for the suture-line to become simplified, and occasionally (Tissotia) it mimics the type seen in the Triassic Ceratites. Of the belemnites, Belemnitella is wide-spread in northern seas in the Upper Seno nian, and Actinocamax in the Senonian of north-west Europe undergoes progressive changes which render it useful as a time index; the irregularly-shaped Duvalia is characteristic of the Mediterranean Neocomian, and Cylindroteuthis of the Boreal. Both the ammonoids and the belemnites became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous.

Of the five classes of the Vertebrata, the mammals and birds are of infrequent occurrence in the Cretaceous, but the reptiles and fishes are represented by many genera and species; the Amphibia are not definitely known. Generally, the vertebrates of the Lower Cretaceous are closely allied to Jurassic types, while the higher beds of the Upper Cretaceous are distinguished by the appearance of forms ancestral to those which flourished in the early Tertiary. Thus the fishes may be divided into two groups : a Lower Cretaceous group, characterised by forms closely allied to Jurassic genera; and an Upper Cretaceous group, in which both the bony and the cartilaginous fishes show a marked resemblance to their modern representatives which are found in the ocean depths. Nearly complete skeletons of cartilaginous fishes occur in the Upper Cretaceous of Westphalia and Mt. Lebanon; in the English Cretaceous are found representatives of the dogfishes (Scyllidae), the sharks (Lamnidae) and skates (Ptychodus, a gigantic, primitive and extinct form). The bony fishes are represented in the English Wealden. (Lepidotus), and are known in the uppermost Cretaceous beds of south Scandi navia, northern France, Persia, India and Brazil. As a whole, the Upper Cretaceous fish fauna appears to be more closely allied to the modern fauna than are the mammals, birds and reptiles.

The Mesozoic is often termed the "Age of Reptiles," and in the Cretaceous the reptiles are still the dominant vertebrates, although not so prolific in species and individuals as in the Jurassic period. The dinosaurs (q.v.) are the most powerful group of Cretaceous animals; they often attain a length of 3o feet, but possess extremely small brain-cavities. Both herbivorous and carnivorous forms are found. The herbivorous dinosaur, Iguanodon, occurs in the Lower Cretaceous of England, and nearly complete skeletons have been obtained from the Wealden of Bernissart, Belgium. Dinosaurs are also very abundant in the Cretaceous of North America ; they include Tyrannosaurus, a predaceous form armed with sabre-like teeth and sharp claws; Trachodon, duck-billed and probably living in shallow, muddy waters; Stegosaurus, with a median row of plates and spines along its back; and Triceratops, with head armed with horns and a massive bony frill. The majority of the remaining reptiles are aquatic forms. The "sea-serpents" are extremely elongated forms, with powerful flippers and long tails. Ichthyosaurs and plesio saurs are less common than in the Jurassic. The pterosaurs (Ornithocheirus), the remarkable flying lizards, attain their maxi mum development ; one digit of each "hand" is prolonged, prob ably serving as a support for the flying membrane (see PTERO DACTYL). The crocodiles (Goniopholis) show many similarities to present day forms, and the marine turtles are in their external structure definitely modern in type. Lizard-like animals (Dolicbo saurus) are known, and true snakes appeared towards the later part of the period.

Birds are represented by the well-known toothed forms Hes perornis (a giant diving bird) and Ichthyornis (built for powerful Hight) ; both are round in the Upper Cretaceous of Kansas.

Mammals are rare. The most primitive forms are the multi tuberculate mammals; they were probably very small, and are known only by diminutive teeth and fragmentary jaws from the Wealden of Sussex and the Upper Cretaceous of North America. The marsupials are represented by opossum-like creatures, which occur in the Upper Cretaceous of Wyoming and Patagonia. The higher mammals are unknown in Cretaceous rocks.

See PALAEONTOLOGY, MULTITUBERCULATA, ORNITHOLOGY, MAM MALIA, REPTILES. (A. G. B.)