Crete

CRETE, after Sicily, Sardinia and Cyprus the largest island in the Mediterranean, situated between 34° 5o' and 35° 4o' N. lat. and between 23° 3o' and 20' E. long. Its north-eastern extremity, Cape Sidero, is distant about no m. from Cape Krio in Asia Minor, the interval being partly filled by the islands of Car pathos and Rhodes; its north-western, Cape Grabusa, is within 6o m. of Cape Malea in the Morea. Crete thus forms the nat ural limit between the Mediterranean and the Archipelago. The area of Crete is 8,616 sq.km. or about 3,320 sq.m. Population (1928): Department Chief town Canea 111,513 Canea Heraclion 138,567 Heraclion (Candia) 33,404 Rethymno 68,18o Rethymno 8,632 Lasithion (Lassithi) 68,i67 Agios Nicolaios 1,600 The island is of elongated form ; its length from east to west is 16o m., its breadth from north to south varies from 35 to 71 m. The northern coast-line is much indented. On the west two narrow mountainous promontories, the western terminating in Cape Grabusa or Busa (ancient Corycus), the eastern in Cape Spada, shut in the Bay of Kisamos; beyond the Bay of Canea, to the east, the rocky peninsula of Akrotiri shelters the magnificent natural harbour of Suda (81 sq.m.), the only completely protected anchorage for large vessels which the island affords. Farther east are the bays of Candia and Mallia, the deep Mirabello Bay and the Bay of Sitia. The south coast is less broken, and possesses no natural harbours, the mountains in many parts rising almost like a wall from the sea; in the centre is Cape Lithinos, the southern most point of the island, partly sheltering the Bay of Mesara on the west. Immediately to the east of Cape Lithinos is the small bay of Kali Limenes or Fair Havens, where the ship conveying St. Paul took refuge (Acts xxvii. 8). Of the islands in the neigh bourhood of the Cretan coast the largest is Gavdo (ancient Clauda, Acts xxvii. 16), about 25 m. from the south coast at Sphakia, in the middle ages the see of a bishop. On the north side the small island of Dia, or Standia, about 8 m. from Candia, offers an incon venient shelter against northerly gales. Three small islands on the northern coast—Grabusa at the north-west extremity, Suda, at the entrance to Suda harbour, and Spinalonga, in Mirabello Bay—remained for some time in the possession of Venice after the conquest of Crete by the Turks. Grabusa, long an impregnable fortress, was surrendered in 1692, Suda and Spinalonga in 1715.

Natural Features.—The greater part of the island is occupied by ranges of mountains which form four principal groups. In the western portion rises the massive range of the White Mountains (Aspra Vouna), directly overhanging the southern coast with spurs projecting towards the west and north-west (highest summit, Hagios Theodoros, 7,882 ft.). In the centre is the smaller, almost detached mass of Psiloriti ("illitXopftriov, ancient Ida), culminat ing in Stavros (8,193 ft.), the highest summit in the island. To the east are the Lassithi mountains with Aphenti Christos (7,165 ft.), and farther east the mountains of Sitia with Aphenti Kavousi (4,850 ft.). The Kophino mountains (3,888 ft.) separate the central plain of Messara, from the southern coast. The isolated peak of Iuktas (about 2,700 ft.), nearly due south of Candia. was regarded with veneration in antiquity as the burial-place of Zeus. The principal groups are for the greater part of the year covered with snow, which remains in the deeper clefts throughout the summer; the intervals between them are filled by connecting chains which sometimes reach the height of 3,00o ft. The largest plain is that of Monofatsi and Messara, a fertile tract extending between Mt. Psiloriti and the Kophino range, about 37 m. in length and io m. in breadth. The smaller plain, or rather slope, adjoining Canea and the valley of Alikianu, through which the Platanos (ancient Iardanos) flows, are of great beauty and fer tility. A peculiar feature is presented by the level upland basins which furnish abundant pasturage during the summer months; the more remarkable are the Omalo in the White Mountains (about 4,00o ft.) drained by subterranean outlets (KraVoOpa), Nida (els riv "IBav) in Psiloriti (between 5,000 and 6,000 ft.), and the Lassithi plain (about 3,00o ft.), a more extensive area, on which are several villages. Another remarkable characteristic is found in the deep narrow ravines ((Papayy(a), bordered by precipitous cliffs, which traverse the mountainous districts; into some of these the daylight scarcely penetrates. Numerous large caves exist in the mountains; among the most remarkable are the famous Idaean cave in Psiloriti, the caves of Melidoni, in Mylopotamo, and Sarchu, in Malevisi, which sheltered hundreds of refugees after the insurrection of 1866, and the Dictaean cave in Lassithi, the birth-place of Zeus. The so-called Labyrinth, near the ruins of Gortyna, was a subterranean quarry from which the city was built. The principal rivers are the Metropoli Potamos and the Anapothiari, which drain the plain of Monofatsi and enter the southern sea east and west respectively of the Kophino range ; the Platanos, which flows northwards from the White Mountains into the Bay of Canea; and the Mylopotamo (ancient Oaxes) flowing northwards from Psiloriti to the sea east of Retimo.

Geology.—The metamorphic rocks of western Crete form a series some 9,00o to io,000 ft. in thickness, of very varied corn position. They include gypsum, dolomite, conglomerates, phyllites and a basic series of eruptive rocks (gabbros, peridotites, serpen tines). Glaucophane rocks are widely spread. In the centre of the folds f ossilif erous beds with crinoids have been found, and the black slates at the top of the series contain Myophoria and other fossils, indicating that the rocks are of Triassic age. It is, how ever, not impossible that the metamorphic series includes also some of the Lias. The later beds of the island belong to the Juras sic, Cretaceous and Tertiary systems. At the western foot of the Ida massif calcareous beds with corals, brachiopods (Rhynchonella inconstans, etc.) have been found, the fossils indicating the horizon of the Kimmeridge clay. Lower Cretaceous limestones and schists, with radiolarian cherts, are extensively developed; and in many parts of the island Upper Cretaceous limestones with Rudistes and Eocene beds with nummulites have been found. All these are involved in the earth movements to which the mountains of the island owe their formation, but the Miocene beds (with Clypeas ter) and later deposits lie almost undisturbed upon the coasts and the low-lying ground. With the Jurassic beds is associated an extensive series of eruptive rocks (gabbro, peridotite, serpen tine, diorite, granite, etc.) ; they are chiefly of Jurassic age, but the eruptions may have continued into the Lower Cretaceous. The arrangement of the rocks is further complicated by a great thrust-plane which has brought the Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous beds upon the Upper Cretaceous and Eocene beds.

The structure of Crete is best understood as a part of the great mountain arc, or scheme of arcs which stretches southward in the Dinaric Alps and fingers out into the southward projecting pen insulas of Greece. Some of these are conjecturably related to the Capes on the western part of the north coast of Crete, the islands of Cerigo and Cerigotto forming intermediate links. Within the island apparently the directive lines curve into the west-east direction, represented in two chains, one running from the west end north of the Mesara plain and the other stretching eastward between that plain and the southern coast. They are to be looked upon as overlapping fragments of mountain-arcs linked, eastwards, with Karpathos, Rhodes and the Lycian Taurus. The Graeco Creto-Asiatic curve, together with the Lycian-Cypriote-Tauric curve farther east form the southward projecting Tauro-Dinaric arc of the Alpine system, one of a great series of arcs all project ing in the same way on the southern flank of the Alpine system. The others are the Arc of the south side of the west Mediter ranean, the Iranian Arc, the crushed-in Hindu-Kush Arc, the Himalayan Arc and the Malayan Arc. South of these, usually beyond a depression of some kind, are the old blocks of Africa, Arabia, the Deccan and Australia. The Aegean Sea is essentially a sinking, in a relatively recent geological period, of the area within the Cretan arc. The occurrence of remains of the small Hippopotamus Pentlandi in Crete in recent deposits shows that the island must still have been connected with the mainland in Pliocene times and that the hippopotamus long survived, in the island, in a dwarfed form ; the analogy of the dwarf elephants of Malta may be recalled.

Climate.—The temperature in January may retain an average of 5o° or even nearly S4° in the lowlands while the summer on the Mesaran plain is hot and malarious. The relief of Crete is, however, so marked that on the heights snow may fall in autumn and lie till the beginning of the next July. The steppe-winds from the north may blow with such force across the Aegean Sea as to prevent in many exposed places any growth of trees. The winds from the African land mass also blow across to Crete affecting its southern side. In winter the commonest winds at Candia are northerly and southerly; in summer, winds with a westerly com ponent are important.

The mean temperatures at Candia are: January 50 May 68° September February 52° June October 67° March 55° July 78° November 61° April 61° August 79° December 55 with a mean maximum (daily) of 83.5°, and one of 86° for Canea, occurring most often in July and August, the mean maximum (monthly) being as high as 97.5° (recorded for June) in which month a record of ioi.8° has been made. The mean minimum (monthly) varies from 4o° in February to 68° in August with a record of 33° in February. The temperature range (monthly) is greatest in spring and autumn when it may reach 3 2 ° ; it is down to 2o° in August.

The mean rainfall at Candia is as follows: January 3.39 May o•48 September o•78 February 3.23 June o-o9 October 1.81 March I•97 July 0•12 November 3.58 April 0•63 August o•35 December 3.98 Vegetation.—The forests which once covered the mountains have for the most part disappeared and the slopes are now desolate wastes. The cypress still grows wild in the higher regions; the lower hills and the valleys, which are extremely fertile, are covered with olive, and in some parts with carobs. Oranges and lemons also abound, and are of excellent quality. Chestnut woods are found in the Selino district, and forests of the valonia oak in that of Retimo. Pears, apples, quinces, mulberries and other fruit-trees flourish, as well as vines. Though the Madeira vineyards have been twice planted with stock from Malavisi province, the modern Cretan wines no longer enjoy the reputation of mediaeval "Malvoisie." Tobacco and cotton succeed well in the plains and low grounds, though not at present cultivated to any great extent.

Animals.—Of the wild animals of Crete, the wild goat or agrimi (Capra aegagrus) alone need be mentioned; it is still found in considerable numbers on the higher summits of Psiloriti and the White Mountains. The same species is found in the Caucasus and Mount Taurus, and is distinct from the ibex or bouquetin of the Alps. Other animals of interest are the moufflon, said to be an ancestor of the domestic sheep, and the porcupine. Crete, like several other large islands, enjoys immunity from dangerous serpents—a privilege ascribed by popular belief to the intercession of Titus, the companion of St. Paul, who according to tradition was the first bishop of the island, and became in con sequence its patron saint. Wolves also are not found in the island, though common in Greece and Asia Minor. The native breed of mules is remarkably fine.

Population.—The population of Crete under the Venetians was estimated at about 250,000. After the Turkish conquest it greatly diminished, but afterwards gradually rose, till it was sup posed to have attained to about 260,000, of whom about half were Mohammedans, at the time of the outbreak of the Greek revolution in 1821. The ravages of the war from 1821 to 183o, and the emigration that followed, caused a great diminution, and the population was estimated by Pashley in 1836 at only about 130,000. In the next generation it again materially increased; it was calculated by Spratt in 1865 as amounting to 210,000. Ac cording to the census taken in 1881, the complete publication of which was interdicted by the Turkish authorities, the population of the island was 2 79,165, or 3 78 to the square kilometre. Of this total, 141,602 were males, 137,563 females; were literate, 242,114 illiterate; 205,01 o were orthodox Christians, Muslims, and 921 of other religious persuasions. The Muslim element predominated in the principal towns, of which the population was—Candia, 21,368; Canea, 13,812; Retimo, 9,274. In June 190o a Greek census registered a population of 301,273, the Christians having increased to 267,266, while the Muslims had diminished to 33,281. Both Muslims and Christians are of Greek origin and speak Greek. Pop. (1928) 386,427.

Towns.—The three principal towns are on the northern coast and possess small harbours suitable for vessels of light draught. Candia, pop. 33,404, former capital, see of the archbishop of Crete, officially styled Heraclion, is surrounded by remarkable Venetian fortifications and possesses a museum with a valuable collection of objects found at Cnossus, Phaestus, the Idaean cave and elsewhere. Canea (mod. Gk. Chanici), the seat of govern ment since 1840 (pop. 26,604), is built in the Italian style; its walls and interesting galley-slips recall the Venetian period. The residences of the governor and of the foreign consuls are in the suburb of Halepa. Retimo (PE6vµvos) is, like Canea, the see of a bishop (pop. 8,632). The other towns, Hierapetra, Sitia, Kisamos, Selino and Sphakia, are unimportant.

Production and Industries.

Owing to the volcanic nature of its soil, Crete is probably rich in minerals. Recent experiments lead to the conclusion that iron, lead, manganese, lignite and sulphur exist in considerable abundance. Copper and zinc have also been found. A large number of applications for mining con cessions have been received since the establishment of the more civilized government. Olive production, always the principal source of wealth, has been increased since the island was annexed to Greece by the planting of young trees and improved methods of cultivation which the Government is endeavouring to promote. The orange and lemon groves till lately suffered considerably, but new varieties of the orange tree are now being introduced, and an impulse is being given to the export trade in this fruit by re moval of the restriction on its importation into Greece. Agricul ture is still in a primitive condition; notwithstanding the fertility of the arable land the supply of cereals is far below the require ments of the population. A great portion of the central plain of Monofatsi, the principal grain-producing district, long lay fallow owing to the exodus of the Moslem peasantry. The cultivation of silk cocoons, formerly a flourishing industry, has greatly de clined in recent years, but efforts are now being made to revive it. There are few manufactures. Soap is produced at numerous factories in the principal towns, and there are distilleries of cognac at Candia.

Constitution and Government.

During the past half-cen tury the affairs of Crete have repeatedly occupied the attention of Europe. Owing to the existence of a strong Mussulman minority among its inhabitants, the warlike character of the natives, and the mountainous configuration of the country, which enabled a portion of the Christian population to maintain itself in a state of partial independence, the island has constantly been the scene of prolonged and sanguinary struggles in which the numerical superiority of the Christians was counterbalanced by the aid rendered to the Moslems by the Ottoman troops. This unhappy state of affairs was aggravated and perpetuated by the intrigues set on foot at Constantinople against successive governors of the island, the conflicts between the Palace and the Porte, the duplicity of the Turkish authorities, the dissensions of the repre sentatives of the great powers, the machinations of Greek agi tators, the rivalry of Cretan politicians, and prolonged financial mismanagement. A long series of insurrections—those of 1821, 1833, 1841, 1858, 1866-1868, 1878, 1889 and 1896 may be especially mentioned—culminated in the general rebellion of 1897, which led to the interference of Greece, the intervention of the great powers, the expulsion of the Turkish authorities, and the establishment in 1899 of an autonomous Cretan government under the suzerainty of the sultan, with Prince George of Greece as high commissioner of the protecting powers. After his resignation in 1906, the modified constitution of February 1907 dispensed with exceptional legislative and administrative powers. An elected chamber exercised complete financial control, and two councillors responsible to the chamber formed a kind of cabinet. Since the cession of Crete by Turkey to Greece in 1912, the island has been administered as a province of the Greek kingdom with a governor general. Almost all the Moslem natives have emigrated, or become "Tripolitan protected subjects" of Italy, or become merged in the orthodox population; their only coherent settlements now being in the islands of Cos and Rhodes. On the other hand, Crete has received its full share of the Greeks expelled from Asia Minor in 1922, and they have greatly increased the production of sultana raisins.For administrative purposes the Turkish departmental divisions have been retained. There are 4 prefectures (formerly sanjaks) each under a prefect; these are Canea, Rethymno, Herakleion (Candia) and Lasithion. These in turn are divided into 23 eparchies (formerly kazas) . For municipal and communal gov ernment, the island is divided into 86 communes, each with a mayor, an assistant-mayor, and a communal council elected by the people. The councils assess the communal taxes, maintain roads and bridges, and generally superintend local affairs. Public order is maintained by a force of gendarmerie.

Religion and Education.

The vast majority of the popula tion belongs to the Orthodox (Greek) Church, which is governed by a synod of eight bishops under the presidency of the metro politan of Candia. Education is nominally compulsory.Improved communications are much needed for the transport of agricultural produce, but the state of Greek finances does not admit of adequate expenditure on road-making and other public works. The prosperity of the island depends on the development of agriculture.

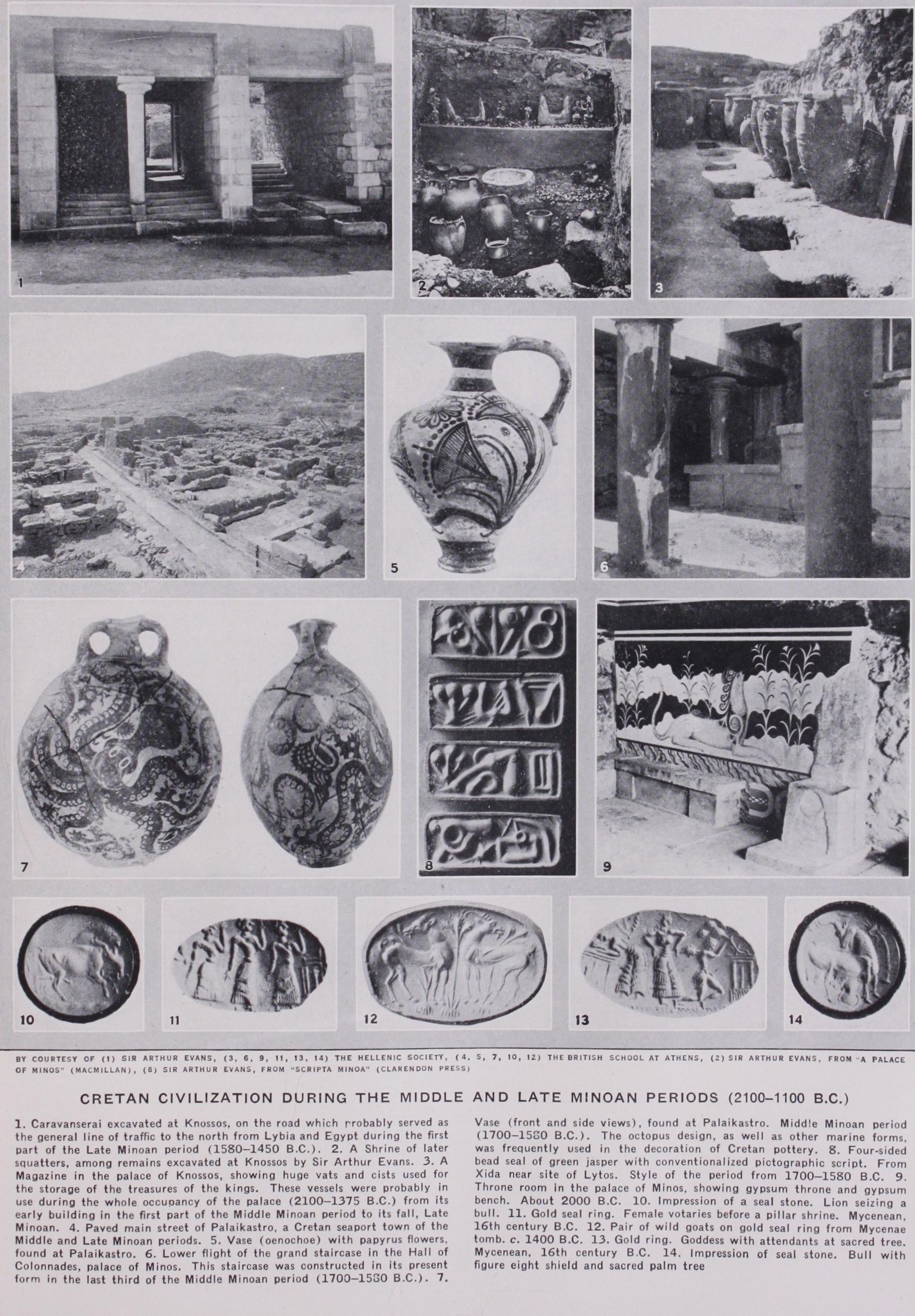

History of Excavations.

The archaeological importance of Crete lies chiefly in its prehistoric remains, which attest the development in the island during the Aegean Bronze age of a culture at least equal in aesthetic and material achievement to the contemporary civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. This Cretan culture extended in its maturity to the whole of Greece, and exercised considerable influence in more distant regions of Europe. Ancient literary records had led several scholars to look to Crete for the origin of the Mycenaean art which Heinrich Schliemann and others had revealed in Greece in the second half of the 19th century, but the disturbed political condition of the island at that time was an obstacle to methodical excavation. Schliemann visited Crete in 1886 and recognized a Mycenaean palace at Knossos, but was restrained from indulging his en thusiasm in the excavation of that difficult site by his inability to come to a financial agreement with the proprietors. An Italian mission, actively directed by Federigo Halbherr, and supported after 1893 by the Archaeological Institute of America, had explored and excavated in many districts since 1884, but with no special interest in any period of antiquity.The first investigator who went to Crete with the purpose of defining its place in Aegean civilization was Arthur Evans, of the University of Oxford. He made his first visit in 1894, in search of a class of sealstones engraved with pictographic char acters which he had identified as Cretan, and in the same year acquired part ownership of the land at Knossos. But it was not till 1900, when the provisional Greek Government was established, that Evans was able to complete the purchase of the palace site and to begin his excavations. Since that time the work at Knossos has not stood still. Later in the same year Halbherr initiated the excavation of Phaistos. A small palace at Hagia Triada, between Phaistos and the southern sea, was also dug by the Italian mis sion. The American Exploration Society, an organization affiliated to the University of Pennsylvania, sent an expedition to the district of Siteia, which excavated town-sites at Gournia and Vasiliki in 1901. The work in this district was ably carried on by Richard Seager until his premature death in Crete in 1925.

With the support of American universities and museums and of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, he excavated houses and tombs in the islands of Pseira and Mochlos in the Gulf of Mirabello, and tombs at Pachyammos on the isthmus of Hierapetra. Other important cemeteries were explored by Ameri cans in the same district at Sphoungaras and Vrokastro. The British School of Archaeology at Athens excavated houses and tombs at Knossos, cave-sanctuaries at Psychro and Kamares, and towns at Zakro and Palaikastro, at the eastern end of the island. It is an unexplained fact that no prehistoric remains have yet been identified in the western half of Crete.

The field-work of the Greek authorities has been active and efficient, but the Government has liberally allowed foreign workers to undertake the more extensive excavations, using its own re sources mainly to deal with the numerous accidental finds of tombs or buildings and the rapid accumulation of material in the Cretan Museum at Herakleion (Candia) . The nucleus of this unique collection had been formed by the local archaeological society, the Syllogos, in the difficult times of Turkish rule. It was housed by the Greek Government in the old barracks until the new museum was built in z 908, but this commodious edifice was not designed to resist earthquakes, which are a source of frequent and sometimes catastrophic destruction in Crete. In a slight shock, in June 1926, considerable, though not irreparable, damage was done to pottery and fresco-paintings by the fall of plaster ceilings. It is more than likely, so long as the building stands in its original form, that its total collapse will some day bury the collection. Since all important objects found in Crete are bound by Greek law to be kept in this museum, it is fortunate that most of them have been duplicated by mechanical reproductions, which are housed in many museums of Europe and America. The first Cretan ephor of antiquities and director of the Museum was Joseph Khatzidakis, who had been president of the Syllogos. His discoveries include two palaces, a small one at Tylissos, west of Knossos, which he excavated, and a large one at Mallia, on the east, which he transferred to the French School of Archaeology. His successor, Stephanos Xanthoudidis, explored houses at Khamaizi and Nirou Khani, an ossuary cave at Pyrgos, and an important series of early beehive-tombs in the Mesara plain.

Nomenclature and Chronology.

In order to mark a dis tinction between the pure Cretan culture and its colonial (My cenaean) form, which may be supposed, at least in its latest phases, to contain some Mainland (Helladic) elements, Evans proposed the name Minoan for the Cretan Bronze age. The term has no particular reference to the legendary Minos, thalassocrat of an Aegean empire and judge in Hades; indeed tradition seems to point to at least two kings of that name, which may have been a dynastic title. Evans' chronological scheme is a symmetrical framework of nine periods. There are three main periods, Early, Middle and Late Minoan, representing the main artistic phases in the pottery viewed as the index of Aegean art. Each main period is divided into three numbered phases, I., II., III., on the natural principle of its rise, maturity and decline. The names of the nine periods are ordinarily abbreviated to their initial letters and the numerals : E.M.I., etc. Absolute chronology rests upon recip rocal contacts with foreign countries, chiefly with Egypt. The synchronisms and dates of the nine Minoan periods are as follows : It has been found possible to classify the M.M. and L.M. ma terial into earlier and later phases of each period, M.M. I.a, M.M. I.b, etc.

Egyptian Contacts.

Contact with Egyptian art is visible throughout the Cretan prehistoric age. Neolithic and E.M. stone vases reflect Predynastic and Old Kingdom types. Devices cut on M.M. seals resemble those of Middle Kingdom scarabs, L.M. architectural and ceramic painting was strongly influenced by Nilotic motives, and in several Theban tombs of early Dyn. XVIII. are pictures of Cretan envoys bearing vessels of L.M. I. style. More definite synchronisms are afforded by finds of foreign products on Cretan sites, and of Minoan pottery in Egypt. Frag ments of predynastic stone bowls have been found in Neolithic deposits at Knossos. M.M. II.b pottery has been found in Egypt in Dyn. XII. rubbish heaps at Lahun and in Dyn. XII. graves at Abydos and Harageh. An alabaster lid bearing the cartouche of the Hyksos king, Khyan, occurred in a M.M. III.a context in the palace of Knossos, and part of an inscribed diorite statuette of Dyn. XII.–XIII. was associated there with the M.M. II.b stratum. L.M. I. and L.M. II. painted vases have been excavated from Dyn. XVIII. graves and houses at Sakkara and Gurob, and a peculiarly cogent contact is the presence of numerous L.M. III.a potsherds (probably of Mycenaean fabric) in remains of the city of Amen hotep IV. (Akhenaten) at El Amarna, which existed only from 1375 to r 3 5o B.C. Minoan pottery has not been found in Egypt in contexts later than Rameses II. Its absence is doubtless due to political disturbances in the Aegean about that time, which are noted in the Egyptian records. The same disturbances appear to have caused the downfall of the Minoan power and culture, and to have closed the period of the Greek Bronze age.

Palaces and Towns: Architecture.

(See also ARCHITEC TURE, Minoan.) The most notable monuments are the palaces, and the palace of Knossos is the largest, best preserved, and most thoroughly investigated. The general aspect of a Minoan palace is a vast conglomeration of buildings around a square courtyard, with certain regular details, but no general symmetry of design. This effect may be largely accidental, the result of long-continued habitation and rebuilding, but it is partly due to a predilection for irregular sites, a peculiarity also of Minoan town-planning. There was sometimes a difference of several storeys between the ground-floors in one building. Skilful use was made of varying levels to admit light and air to interior rooms, one roof serving as a terrace to the apartments next behind it. The ordinary system of interior lighting was through colonnades or windows opening into small deep courts or shafts. Long porticos, borne by massive square or circular pillars, gave shade and shelter in the great courtyards. The courts are paved with flag-stones and cement, and are traversed by slightly raised foot-paths. Wide flights of steps mount from one courtyard to another, and an odd arrangement of another flight, set at right angles to the first but leading nowhere, forms a kind of theatre or reception area. The palace entrances were square porticos with a single central column in front, and two doorways behind giving access to a corridor and a porter's lodge.A typical internal feature is a range of doorways with doors fold ing back into square jambs. Inside the rooms, round columns carried the ceiling in the alignment of these piers. From such a scheme, by which the open doors convert an outer wall into a colonnade, the Greek megaron, with its anteroom and portico, may well have been derived. The columns tapered downwards ; they were made of wood, and had variegated stone bases which are still in place. The columns have decayed, but in some instances their forms were moulded in the surrounding earth. In a large house (the Little Palace) at Knossos a shaft had left the impression of its convex fluting.

Columns were often set on stone balustrades. This device ap pears in its most elaborate form in the grand staircase of Knossos, and its simplest application is seen in small apartments with sunk floors approached by steps, which are a constant feature of all palaces. They were once thought to be baths, but it is likely that they were lustral chambers in which oil or water had some ritual use. Where columns stood in upper rooms the floors were sup ported by massive pillars at the same points in the rooms below. This was indeed a necessary method of construction where upper floors were made of stone and joists could only be of wood, but it became a sort of fetish, through the extension of baetylic cult to the pillars of the house, with very real significance in a land of earthquakes. The pillar-crypt was a domestic sanctuary. Vats for libation-offerings are sunk in the stone floors, and double-axes set on pedestals beside the pillars. The stones of pillars in such crypts at Knossos and Mallia are incised with the sign of the double-axe, in reference to their sacred function. But the double axe was one of many mason's marks, and was used in other places where its religious meaning is not evident.

Interior walls were usually built of rubble, set with mortar in a timber frame, and were finished with a plaster face. The outer walls were solid stone, or had stone facing. The heaviest and finest ashlar masonry is found in the earliest portions of the palace structures (M.M. I.), but even here there was a tendency to use timber courses, particularly on the lines of window heads and sills. The stone-faced walls have thin orthostatic slabs set opposite each other on a solid plinth and clamped together cross wise with wooden bars, the space between them being filled with rubble. But even the stone veneer bears traces of external plaster.

Knossos, Plan.

The palace of Knossos lies on a low hill in the broad valley of the river Kairatos. The top of the hill, which is largely formed by Neolithic settlements of great antiquity, was levelled to make the central court. This is a long rectangle running north and south, and entirely enclosed by buildings. Outside the palace on the west is another paved court-yard. The area covered by the courts and buildings is about six acres. The only direct entrance to the central court is in the middle of the short north side. On the east the hill slopes sharply to the river, and here some ground-floor rooms have been preserved entire, together with the last f our flights of the grand staircase that led down to them. This was the domestic quarter, with cool secluded rooms and no direct approach from outside. On the opposite side of the central court were public halls and offices, their further walls bordering the west court. The outer ground-floor contained the magazines, a range of narrow rooms, originally 22 in number, opening from one side of a corridor 200 ft. long. The lower walls here have been preserved for half their height. Large earthenware jars still stand along the walls, and in the stone floors of magazines and corridor are rows of square cists. Some of these have traces of lead linings, and fragments of gold foil bear witness to the storage of treasure at some time ; but their heavily charred stone edges show that at the moment of their final passing out of use they were filled with oil. On the other side of the long corridor, facing the central court, is the throne room, an apartment evidently used for royal ceremonies. It takes the name from a high-backed gypsum chair which stands in the middle of one wall. On either side of the throne are stone benches, and the wall was painted with large grif fins. On the opposite side of the room is a lustral chamber with sunk floor behind a balustrade. An earlier lustral chamber lies at the outer north-west corner of the palace.It is not known if both these sanctuaries were in use at the same time, but their existence points to a continuous association of this quarter with the priestly functions of the king. An entrance to the south-west quarter, opening from the west court, seems to have served his secular state. The processional corridor, lined with fresco-paintings of youths bearing ceremonial vessels, began at this porch, and turned left at the angle of the palace to an inner propylaeum, from which a wide staircase led to the principal hall of the west wing. In the east wing the north end contained the industrial and service quarter. Here were found quantities of fine painted pottery, stone vases in the making and unworked Laconian porphyry, and several magazines with storage-jars. The royal apartments are sunk in a deep cutting in the natural slope of the hill. Problems of drainage were complicated here by the difference of ground-floor levels. The living-rooms lie far below the central court, from which they are approached by the grand staircase. Stone shafts and ducts and terracotta pipes led the storm-water safely and even usefully from roofs and courts and terraces to rain-spouts in the outer walls. Each pipe is tapered and fits into the next with a collar-joint. It is thought that the tapered channel would give a thrust to the water and prevent accumulation of sediment. Beside a secondary staircase, stone ducts conveyed the water gently downhill in a series of convex curves. A latrine on the ground-floor was connected with the main drain and flushed with rain-water. A bathroom in the same suite has a cemented floor and an oval earthenware tub.

More illuminating than any description are the names which the excavator has given to some of these apartments : the Hall of the Colonnades, the Queen's Megaron, the Court of the Distaff, the Room of the Plaster Couch. The stone floor above this quarter lies in its original position. Like the steps and balustrades of the grand staircase it was held up by bricks and timber which fell down from the ruin of the upper storeys, and in the course of excavation the decayed beams were replaced by iron girders. On the upper terrace level, at the south-end of the east wing, is a domestic shrine, in its present condition belonging to the latest period of the palace, but probably occupying the site of the original chapel. Its furniture was found in place, crude terracotta idols of a goddess, her doves and votaries, vessels for offerings, and sacred horns for holding double-axes. Similar, but earlier and richer relics of another shrine, were found in two large cists (the temple repositories) in the floor of a room in the west wing. These are coloured faience statuettes of a snake-goddess and two priest esses, with votive robes and ornaments.

Knossos, History.

The chronology of the palace has been defined by observation of successive floor-levels, styles of building and deposits of pottery. It is clear that the existing plan was formed in its main outlines at the beginning of M.M. I. All identifiable remains of the E.M. period were cut away when the site was levelled for this structure. In its earliest form it seems to have consisted of a number of separate blocks built round the central court, some at least of which were fortified. The massive masonry seen, for instance, in the northern entrance belongs to these early works. In the course of M.M. I. the original island blocks were united in a single circuit wall; the gangways between them became corridors, and the entrances and general disposition of the existing quarters were laid out. The final consolidation of the building seems to have been achieved in M.M. II.a. It was then that the eastern slope was cut away to admit an enlargement of the residential quarter. At the end of M.M. II. the palace seems to have been partly destroyed. Signs of a similar catastrophe are visible at Phaistos, and the event was connected, at least in time, with the collapse of the Middle Kingdom in Egypt and the beginning of Hyksos raids. The political condition of Crete at the time is not known.There was, however, no break in the continuity of Minoan cul ture, nor any diminution of material prosperity at Knossos or Phaistos. Both palaces were rebuilt at once and on a grander scale. The final arrangements of the domestic quarters date from this epoch (M.M. III.a), and its grand staircase then received its present form. Another structural catastrophe occurred at the end of the period (M.M. III.b) involving the destruction by fire of a large part of the west wing, and plundering of its treasure-cists. The buildings on the east slope were not so severely damaged, but in the rebuilding at the beginning of L.M. I. a good deal of work was done on each side of the cutting. There is reason for supposing that these destructions were primarily due to earth quakes. The L.M. rebuilding was competent and thorough, but shows in many places a reduction in extent. Much of the existing decoration naturally belongs to the latest phase of the palace as a whole, the so-called Palace period (L.M. II.) which is marked by highly decorative art and extreme technical facility. At its end there came another destruction, from which the palace never fully recovered. The whole building was burnt, and all the other palaces and towns of Crete were destroyed at the same time. In L.M. III. a there was a partial reoccupation of most of the ruined sites, but with only a shadow of their former grandeur, and with some new elements which seem to have come from Mainland Greece. It looks as if the conquerors of the Minoan mother-country were the Mycenaean colonists. The continual reconstruction of the palace is the reason of its complexity. Blocks originally separate were connected by corridors, which became more and more tor tuous as halls and staircase were altered or added, and the process of adaptation ultimately produced a truly labyrinthine plan.

Viaduct, Road, and Caravanserai.

The most drastic changes which followed the catastrophe of M.M. III. are seen at the south end of the palace. At the south-east angle some huge blocks of masonry were found 20 f t. out of place, having been hurled to that distance by the earthquake shock, demolishing a house in their fall. This house, and another that collapsed with it, were not rebuilt, but were filled in after a religious sacrifice had been offered on the spot to propitiate the earth-shaking power. Relics of the rite were found in skulls of long-horned bulls and fragments of tripod-altars. At the same time the most magnificent entrance to the palace, at the south-west corner, was destroyed and not rebuilt, but its place was taken in the following period by private houses, which thus encroached upon the palace site. The original entrance was approached by a stepped portico, which climbed the bank of a stream that feeds the Kairatos. In con nection with it, on the further bank, there stand the piers of a colossal viaduct by which the southern road was led across the bed of the torrent. Stepped intervals between the piers, like the spillways of a modern dam, gave passage to the water. Sections of the road itself have been traced across the island, over the low watershed of the central mountains and through the Mesara plain to the Libyan sea. It is visible in ancient cuttings, in retaining walls, and in guard-houses, residences and shrines along its route. Its terminal port was at Komo, near Phaistos, which it also linked with Knossos, but it doubtless served as the general line of traffic to the north from Libya and Egypt. At the Knossian road-head, near the viaduct, Evans also found a caravanserai. It had a front yard backed with stables and store-rooms, and upper storeys built of brick. There is a refectory in the form of a stepped porch, adorned with a painted frieze of partridges and hoopoes. Attached to this is a smaller porch containing a sunk basin for foot-washing. A small spring-chamber near the caravanserai was choked with gypsum incrustation, but when this was cleared the water again rose in its ancient place, and the whole system was restored to working order.

Phaistos and Hagia Triada.

Phaistos has an imposing posi tion on a mountain spur in the Mesara, 30o ft. above the plain. The palace occupies one summit, on two others were buildings of the town. It is more spacious though smaller than Knossos, and its plan is less complex, because the visible remains belong mostly to one period. The original palace, built in M.M. I. was destroyed as Knossos was in M.M. II., but less use was made of early ele ments in the M.M. III. rebuilding. After the general destruction at the end of L.M. II. it was not reoccupied. The existing plan is laid out on four slightly different levels. The central court meas ures about so yd. by 25, and has a portico on each long side. The colonnaded hall of state is approached by a noble stairway. The surviving furniture and wall-decorations are not remarkable, but a single find of unique importance was made in one of the maga zines, a clay disc bearing pictographic inscriptions. At Hagia Triada, on a lower height of the same ridge, 2 m. from Phaistos and about halfway to the sea, there stands a small palace or villa, which is thought to have been a summer residence of the Phaestian king. It is finely built of ashlar masonry, and the walls stand higher than is usual on Minoan sites, but it was a short-lived struc ture, built in M.M. III. and destroyed in L.M.I. There was no earlier palace on its site, and nothing replaced it until the Reoccu pation period (L.M. III.a), when a smaller Mycenaean building was imposed upon its ruins. But its premature destruction was the means of preserving some of the choicest works of Minoan art that exist, particularly some naturalistic fresco-paintings and three carved stone vases.

Mallia, Tylissos, Nirou Khani.

Palaces exist on the north coast at Mallia and Tylissos. That of Mallia is an extensive build ing with a colonnaded court in the monumental style of M.M. I. The remains at Tylissos belong rather to a large house or houses. but their decoration and contents were in true palatial style. A large house was also found at Nirou Khani, mid-way between Tylissos and Mallia. In one of its rooms were four gigantic double axes of bronze, and in another were 4o or 5o tripod-altars. It must have been an emporium for religious furniture.

Towns and Houses.

Many houses have been found at Knos sos, but the town, as a whole, has not been explored. Indeed, its site is too large for exhaustive excavation, and the Greek and Roman occupations have doubtless destroyed much of the Minoan city. Some of the houses are exceedingly well built, and differ from the structures of the palace only in size. Those which en croached upon the palace area after the M.M. III. earthquake had several storeys. A large house on the west side, connected by a paved road with the west court, has been called the Little Palace. It contains a lustral chamber and a pillar-crypt, and in it was found a magnificent libation-vessel in the shape of a bull's head, half life-size, carved in black steatite, with gilt horns, muzzle inlaid with white shell and enamelled crystal eyes. Another palatial house is the so-called Royal villa, which is probably one of a row of summer residences that stood on the river-bank below the domestic quarter of the palace. Even in some ordinary houses the decora tions were not inferior to those of the royal halls ; such are the wall-paintings from the House of the Frescos at Knossos.The perfect type of the provincial town is Gournia. It lies on a low oval hill, to which the houses cling regardless of the slope ; some are approached from the street by steps, others had one storey in front and two or three behind. An enclosing road on each side leads to a small palace, which occupies about 12 times the floor-space of an ordinary house. It is built like Knossos, even to the magazines and a court with stepped reception-area, but in humbler style. The streets of the town are about 5 f t. wide, stone paved, and the houses crowd up to their edges. Some of the cross-streets climb the hill in steps. There is no circuit-wall and the houses are set closely round the palace. In the middle of the town is a built shrine, with furniture of pottery vessels and cult idols. The city flourished in L.M. I. and was partially reoccupied after the general destruction at the end of L.M. II. Its oldest houses are of M.M. date. The palace and some of the larger houses have ashlar masonry, but the ordinary material was rubble.

A few Neolithic structures are known. At Magasa near Palai kastro are a walled rock-shelter and a free-standing house of simple rectangular plan. The floors of two more complex houses were found beneath the pavement of the central court at Knossos. These had fixed hearths, a feature that does not appear again in Crete until L.M. III. An oval house of M.M. I. exists at Khamaizi, but this singular form is more likely to represent an adaptation to the contours of its site than the survival of a primitive plan. Vasiliki has E.M. houses built in the mature Minoan manner, with brick or rubble walls set on stone footings, stiffened with timber framework and plastered with clay and lime. Their roofs were wattled. The clay-plaster is even painted red, foreshadowing later fresco decoration.

No household furniture has survived except pots and pans of earthenware and bronze. Braziers of various kinds were used instead of fixed hearths. A heavy shallow dish supported by three short legs seems most suitable for warming rooms and cooking, and is of ten associated with sacrificial cult. More easily portable are broad-brimmed bowls with long poke-handles, largely used in tombs for fumigation, and fire-boxes, perforated globes sometimes joined to tripod-stands.

Arts: Pottery.

Much of the household pottery is rough un painted ware and looks unattractive beside the painted vases which represent Minoan culture in museums. But decorated ware is abundant, and has a special scientific use apart from its aesthetic interest, since the style of decoration adds to the evidence of shape and fabric numerous distinctive features that make a reliable index of culture and chronology. The Cretan series has been accurately classified in reference to the chronological systems of the Neolithic and Bronze ages. The Neolithic deposit at Knossos has been divided into Lower, Middle and Upper Strata. The Lower pottery is plain dark-coloured ware, in its latest phase approxi mating to the burnished and incised fabrics of the Middle period, the typical Cretan Neolithic style. The decorative patterns are simple rectilinear figures, zig-zags, herring-bones and groups of parallel lines and rows of dots often grouped in triangles. The Upper Neolithic pottery is better fired, showing red or light brown surface, and less elaborately ornamented, both in burnish and incision. With the coming of copper in E.M.I. the pottery kept a sub-Neolithic character, but its fabric was often inferior. A closely-incised bucchero is the best product of the period.Painting began in E.M. II. with rectilinear figures in red-black ferruginous glaze on a natural clay ground. Besides the simple forms of hemispherical bowls and cylindrical cups, flat plates, ladles and little globular pots, with pierced lugs for tie-on lids, which had persisted with slight variation from Neolithic times, some sophisticated and even fantastic forms appear, beaked jugs with loop-handles, and jars with long tubular spouts, which may have been copied from Egyptian or Mesopotamian prototypes in metal. In E.M. III. the mode of decoration was inverted, and the patterns were applied in white paint on a ground of black glaze. In this and the previous period the vase was sometimes covered with the glaze, and fired so as to oxidize in more or less irregular patches of black and red (Vasiliki ware). Curvilinear patterns began in E.M. III., notably the spiral coil, which was apparently introduced from the Cyclades. The potter's wheel was not known in the E.M. age. The manufacture of stone vases was perfected at this time, evidently under influence of Egyptian methods and models, but Minoan stone vessels have the same graceful and elaborate shapes as the pottery, and differ also from their Egyptian relatives in their gay colouring. They are mostly made of breccias and veined marbles, in which the bands of colours are disposed to fit the contours of the pots.

The best examples came from tombs at Mochlos, where a unique series of gold jewels of this early period was also found. These coloured stones, particularly a black marble veined with red and white, seem to have led the vase-painters to the invention of a polychrome style. In many instances the variegated stones were directly imitated, but the normal early types of ornament were simple festoons and bands, together with some rare and strongly stylized naturalistic motives, done in white and various shades of red and yellow on a lustrous black-glaze ground. This is the so-called Kamares ware, a style that is characteristic of all three M.M. periods. Its most brilliant phase was in M.M. I. b. and M.M. II. a. M.M. I. a contains the elements of the style; M.M. II. b displays a loss of vigour and some incipient changes. M.M. III. a shows artistic decadence, following the political ca tastrophe, and M.M. III. b developed a naturalistic impulse which finally destroyed the style.

At the culminating moment in M.M. II. a, the potter's craft was also at its best, just before the introduction of the quick wheel. The clay was worked to eggshell fineness. Waved rims and fluted bodies were copied from delicate metal cups, and heavier vessels had encrusted surfaces. The quick wheel brought industrial uni formity, and put an end to fanciful modelling. In M.M. II. b the first approach to faithful rendering of nature is seen in some groups of crocuses on a vase from the Kamares cave. An octopus on a companion vase is very strongly stylized. There was a grow ing tendency to arrange designs in horizontal bands; another imprint of the quick wheel, and the ornament itself became at tenuated, its colouring less rich. The artistic decadence of M.M. III. a is represented in large quantities of meagrely decorated vases, in which some shapes were extravagantly elongated, a fea ture which belongs to Egyptian vessels of the same date. New forms were inspired by ostrich eggs mounted with tips and feet of metal or faience. Polychromy almost vanished, and the ordi nary type of decoration consists of conventional coils and scrolls in thin white pigment on a faded black ground, or sprinklings of minute white dots in feeble imitation of mottled stone. A still more humble source of inspiration was the accidental trickle made by hasty painting or spilled contents. In M.M. III. b the painters turned definitely to naturalistic subjects, and their first essays of simple leaves and grasses mark the beginning of a new artistic era.

But the new subjects demanded more articulate expression than the old technique allowed. The L.M. age brought a complete return to the original method of painting, which, indeed, had never been quite lost, using the black glaze medium for drawing on the natural clay. Its revival now involved an exceedingly fine finish of the pot. No separate slip was applied, except to large vases of coarse substance, but the clay was smoothed and fired so as to produce a lustrous yellow or pale brown surface. The glaze was also improved in body and lustre, and was fired to a variety of tones from its normal black through brown to red and yellow. Touches of white and red paint were added in L.M. I., but did not long survive. The new exuberance of ornament attached itself to the old geometric motives, sprays of leaves or flowers springing from outer curves of spiral coils or occupying their centres.

Architectural ornaments were adapted from wall-decoration rows of discs and crescents, chequers and triglyphs, mottling and grain ing in imitation of stone and wood. Animals are never represented (though the bull's head occurs), birds rarely, but sea-creatures were favourite subjects in L.M. I. b and later, particularly octo pods, argonauts and shells among rocks and seaweed. This was the beginning of the Mycenaean style. Its immediate development was back to formalism. The style of the Palace period (L.M. II.) is very decorative but often pompous. Large jars with rigid schemes of palm-trees or papyrus, and with painted hands and panels imitating stone and metal mouldings, are a common form. Minoan flowers are seldom true to nature, even in the direct and vigorous renderings of L.M. I. Nilotic lotus and papyrus types were freely blended with the native lily. The lesser pottery of L.M. II. has the formalism of this style without its grandeur, and is a stage on the way to the conventional reminiscences that corn prise the repertory of L.M. III. This is the pottery of the Re occupation period on Cretan sites. It consists of two varieties, the native Cretan (Minoan) style, which reflects the heavy for malism of L.M. II., and a simpler Mainland (Mycenaean) fabric, which is rather an atrophied derivative of L.M. I. The latter is the El Amarna style (135o B.c.) . There is no certain explanation of the co-existence of these two styles in Crete, but they suggest that the great destruction which preceded the reoccupation was the work of Mainland colonists. In the latest phases, L.M. III. b and sub-Mycenaean, it is no longer possible to differentiate Cretan and Mainland pottery.

Fresco-painting.

The decoration of pottery was closely bound to the greater art of fresco-painting, with the notable dif ference that human and animal figures, usual in the wall-paintings, were not until the very latest epoch reproduced on vases. Painted walls and floors were universal in Minoan houses, even on surfaces exposed to weather. The process was true fresco on lime plaster. Some E.M. house-walls at Vasiliki (where the plaster contained a large proportion of brick-earth) were painted red. It is probable that the earliest designs were reproductions of structural forms, grained timber friezes and pilasters, courses of discs representing ends of joists, veined and mottled wainscots imitating stone veneer. Such schemes persisted in the mature periods, and pictorial panels and friezes were inserted in these architectural frames.The earliest known figure-subject is the Saffron Gatherer of Knossos, a blue-painted boy or girl gathering flowers into Kamares bowls in a rocky landscape (M.M. II.) . Its style is still archaic, but before the end of the next period the painters had attained full freedom in their art. The masterpieces of the naturalistic phase (M.M. II. b–L.M. I. a) are landscapes from Hagia Triada, with cats stalking pheasants between rocks and flowers. Similar land scapes came from the House of the Frescoe at Knossos. There, on one fragment, amid luxuriant foliage and delicate flowers is a fountain-jet, on others a blue bird and a Sudanese monkey. Sea scapes are represented by a frieze of dolphins from the Queen's Megaron, and by flying-fish from Phylakopi in Melos. A curious subject, of which several examples exist, is the summary repre sentation in miniature of crowds of men and women in the vicinity of sacred buildings ; probably spectators at a bull-fight or similar public shows. A small panel from Knossos contains a com plete picture of the ceremonial sport of hull-leaping, the human sacrifice offered to the Minotaur in his Labyrinth, the "Place of the Axe." The performers are two girls (white-painted) and a boy. Human figures are represented elsewhere on a larger scale and in elaborate detail.

Painting was also combined with modelling in relief, as in the bust of a woman (Pseira), a bull's head, and a noble figure of a king or god wearing plumes and a lily-crown, who was leading a griffin in a land of flowers and butterflies (Knossos). These belong to L.M. I., as does an important historical subject from the House of the Frescoes, a Minoan officer leading negro soldiers. Proces sional figures were frequent ; one of these is the Cup-bearer, the first great find that was made at. Knossos. Landscapes of the clos ing period are represented by excerpts on large burial-chests. They reproduce the hybrid water-plants and stylized birds of con temporary Egypt.

Sculpture.

Sculpture of large size is poorly represented. That it existed is proved by the stucco reliefs in Crete and the lions of the gateways and two gypsum reliefs from Mycenae, which arc purely Minoan. Small works in steatite or ivory are comparatively numerous. The earliest is a long-legged dog on a steatite vase-lid from Mochlos (E.M. II.) . The finest pieces in the round are an ivory statuette of a boy leaping, probably from a bull-fight (Knossos), the black steatite bull's head from the Little Palace, and a gold and ivory snake-goddess in the Museum of Fine Arts at Boston. Another ivory statuette in an English collection repre sents a boy with arms raised in adoration, and may have been the companion figure to the Boston ivory in a group of the goddess and her son-consort. The snake-goddess, with her priestesses and sacred animals from Knossos, is modelled in faience, and lacks the fine finish of carved work. The same heaviness is seen in cast bronze statuettes, male votaries from Tylissos and elsewhere, a woman from the Troad and another from Hagia Triada, and a group of a man and bull. Three superb examples of sculpture in relief are the Chieftain cup, the Boxer vase, and the Harvester vase from Hagia Triada. They are carved in black steatite, and were, perhaps, plated with gold foil.