Crimean War

CRIMEAN WAR. The causes of the Crimean War, in which Great Britain and France, allies for the first time for two centuries, drifted into war with Russia, were involved if not ob scure. Russia, to whom popular opinion of the times, in flat de fiance of history, attributed a power in arms little short of invinci bility, continued to pursue the policy of expansion towards Con stantinople laid down for her in the legendary will of Peter the Great, and early in 1853 seized the opportunity of a petty re ligious quarrel about "a few Greek priests," to arrogate to herself the unofficial but lucrative role of protector of the Orthodox Christians in partibus infidelium, as a preliminary to an eventual reversion of the bulk of the estate of ("the sick man," as her ruler, tsar Nicholas I., believed Turkey to be.) This line of policy brought her in sharp opposition in the first place to England, who saw in a Russian occupation of Constantinople a potential threat to the overland route to India too formidable to be countered even by the possession of Egypt, which the tsar was ready to bestow on her as the reward of complicity. Nicholas, moreover, on the day when he preferred to address the newly-crowned em peror of France as a friend rather than as a brother, had raised up for himself another and more implacable enemy. Napoleon III. was too good a son of the Catholic Church to acquiesce in the Russian claims to special treatment for Orthodox Christianity in the Ottoman empire; too much a Bonaparte not to wish to re venge 1812 and the occupation of Paris; and too uncertain of his new throne not to welcome a successful war, that first and last thought of an insecure dynasty. The emperor of Austria too, who owed it to the tsar's military aid in 1849 that he still sat on the throne of his fathers, was so nervous of Russia's advance in the Balkans that he was prepared to astonish Europe by his ingratitude and take the side of France and Britain. Amid all these jealous and suspicious rivals Turkish diplomacy pursued a sure but tortuous course, in large measure directed from behind the scenes by the British ambassador, Stratford de Redcliffe, an other man of whom the tsar had made a powerful personal enemy, and to a greater degree than any other individual the author of the Crimean War. A Russian ultimatum was delivered and politely rejected by the Turks. A European congress met and arrived at a solution of the problem which no one understood, and no one but the tsar accepted; and in July 1853 Russia mobil ized and her armies occupied the portion of Turkey lying north of the Danube. A few weeks later a Russian fleet attacked and destroyed a Turkish squadron in the Black sea, despite the pres ence of French and British warships in the Bosporus. After this, war, though still long in coming, was inevitable ; and by March 1854 France and Britain found themselves in alliance with each other against Russia.

In Jan. 1854, as soon as the Allies had decided that the Otto man empire must be protected against the tsar, Sir John Bur goyne, an engineer officer, had been sent to elaborate a scheme for the defence of Constantinople, and gave it as his opinion that this could best be done by fortifying Gallipoli. Marshal Vail lant, the French minister of war, another engineer, concurred, and the Crimean War began ominously, as far as the Allies were concerned, as a defensive war. But in war one cannot defend unless one is attacked, and before the French and British expe ditionary forces had completed their assembly at Varna on the western shore of the Black sea, it became clear that they would not be attacked ; for Russia, in obedience to the ungrateful pres sure of Austria, drew back her army from the captured trans Danube provinces, thus leaving the Allies apparently no casus Belli. But it is easier to let loose the dogs of war than to catch and kennel them again. The expeditionary forces could not be left at Varna, where there had broken out a severe cholera epi demic. Nor was either France or England prepared to bring home troops without something attempted, if not done; so there came up the question of the invasion of the Crimean peninsula, on the southern coast of which was situated Sevastopol, Rus sia's only naval base in the Black sea.

This distinctly formidable enterprise was certainly undertaken, like another and more formidable one, ¢ coeur leger. Little was known of the country; as Prince Albert most sensibly put it, "the first difficulty is the absence of all information as to the Crimea itself." Even the more volatile French court realized this; the great Napoleon was consulted by means of a planchette; two sketches of Sevastopol and Balaklava by Raffet were carefully studied as the possible basis of a plan of campaign ; and the great strategical authority, Jomini, was sought out in the Café Anglais, where, despite the cheerfulness of his surroundings, he could only prophesy disaster. The British cabinet however, observing from a cursory glance of the map that the Crimea was a peninsula, con ceived that there could be nothing easier than for the British fleet to cut it off from the mainland by commanding the isthmus with its guns—nor could there have been but for the fact subse quently discovered, that the depth of the sea on either side of this isthmus was little more than two or three feet. The decisive despatch authorizing the attack on the Crimea, and impressing on its recipient the importance of selecting favourable weather, was sent by the British cabinet to Lord Raglan, the commander-in chief, on June 29; Marshal St. Arnaud, his colleague, received the less precise but probably no less helpful instructions "to act as circumstances might require." On July 18, therefore, the allied generals and admirals held a council of war, at which the invasion of the Crimea was decided on.

The British commander, Lord Raglan, the Fitzroy Somerset of the Peninsular War, had seen no service since 1815, and had spent most of his time at the Horse Guards: a courtly and polished gentleman, his chief merit was that, despite his incurable habit throughout the campaign of referring to his enemy as "the French," he was admirably adapted to lessen the friction inevi table in coalition wars. His French colleague, St. Arnaud, had had a variegated career. He had distinguished himself in Algeria at the siege of Constantine, and had helped to engineer the coup d'etat which placed Napoleon III. on the throne. At the opening of the campaign, however, he was already stricken with a mortal sickness. Omar Pasha, the Turkish commander, who had seen much service in the Near East, was the most experienced soldier of the three. The most remarkable thing about the British divi sional generals was their age ; all with the exception of the duke of Cambridge were approaching 7o, and were of the stock and pipeclay school.

On Sept. 7 the combined forces embarked at Varna, 5 7,00o in all, the largest expedition that had ever set out for war overseas. The "Caradoc," having on board Raglan, Burgoyne and Brown, preceded the flotilla to look for a likely landing place and steamed so close to the Crimean coast that Russian officers could be seen looking at her through their telescopes, and "on perceiving this the English officers took off their hats and bowed." The Rus sian governor of Eupatoria, close to which the Allies decided to land, was equally punctilious; on receiving the formal summons to surrender, he first fumigated the document, then read it, and, realizing that he must yield to superior numbers, insisted that the British and French troops on landing must consider themselves in strict quarantine. The disembarkation took place unopposed, and without a hitch.

The English army at this time knew neither training nor manoeuvres outside the barrack square ; the "picnics" in Surrey, as field days were then called, had taught it little or nothing. Its generals were, as Lord Wolseley said of those of Wellington's day, "mostly duffers" but the men were of that tough stolid stock whose "phlegm" throughout the Peninsula and at Waterloo had never admitted defeat. Whereas in England the army had been hidden away, in France it had been paraded; and French dash and English solidity made a formidable combination. The Russian army was ever behind the times. The regiment belonged to the colonel, not the colonel to the regiment ; peculation and corruption were rife in all branches ; and its tactics were still based on Suvorov's motto, "The bullet's a fool, the bayonet's a fine boy." The Russian soldier was armed with a smooth bore, while the Allies had the Minie rifle ; and so indifferent a marks man was he that at the Alma the men in the rear rank fired over the heads of those in the front. His obstinate courage was, how ever, proverbial, and his priests with the ikons accompanied him on to the battlefield to encourage him to fight to the death.

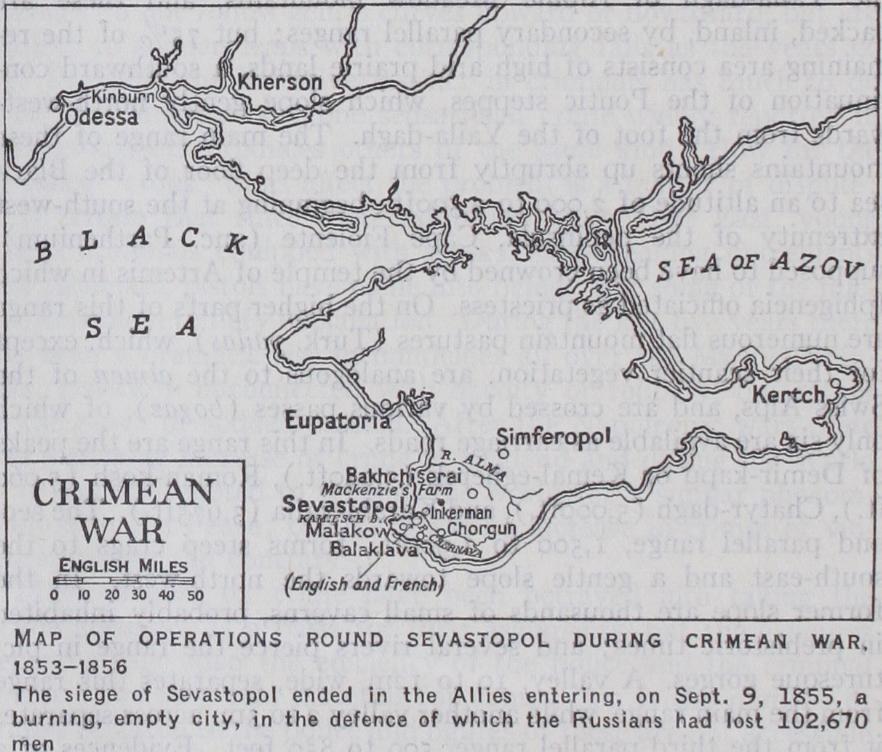

The advance towards Sevastopol, about 3om. away, began on Sept. 19, the French on the right next to the sea, the British in land; the French complained—not for the first or the last time in history—of British slowness. Next day the battle of the Alma was fought. As no combined plan of attack on the Russian posi tion behind the Alma river had been arranged beforehand, co operation between the Allies was conspicuous by its absence, and they fought two actions side by side. An attempt to turn the left of the enemy line miscarried, so the battle degenerated into a purely frontal attack which was eventually successful in establish ing itself on the Russian position. Generalship was equally absent on the side of the Russians where "no one received any orders and every man did what he thought best." The steady advance of the British up the slope across the river made an unforgettable impression on the French general, Canrobert ; they went for ward, he said, "as though they were in Hyde Park!" Some years later, at a Court ball in Paris given in honour of Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort, as he watched the careful precision with which Her Majesty went through the complicated manoeuvres of a quadrille, never faltering, never missing a step, memories of the Alma came back to him, and he cried "The British fight as Victoria dances." The battle was an Allied victory, but as the French cavalry had not yet been landed and Raglan was resolved "to keep his in a band box," there was no pursuit. Two days were spent in burying the dead and evacuating the wounded to the fleet, as no provision for their care had been made. On the 23rd, the advance was resumed, and on the 25th the English, much to their astonishment, all but collided with a Russian column marching at right angles to their front. Menschikoff, the Russian commander believing that the Allies would attack Sevastopol from the north side, was moving the bulk of his army out of the fortress towards Bak shiserai, in order to keep open his communications with the main land. The Allies had no maps of the Crimea, and those in pos session of the Russians were so indifferent that one regiment, after marching steadily for the whole of the loth, finally found itself back in front of Sevastopol. Todleben, Niel and Lord Wolseley have all argued that Sevastopol must have fallen an easy prey to an immediate Allied attack; Burgoyne and Hamley held the contrary opinion. The attempt was not made and the Allies marched solemnly round the fortress and sat down to be siege it in due form, so "playing," as Lord Wolseley said, "into the Russians' hands." The British took the right or eastern flank of the line, as their fleet had already taken possession of the harbour of Balaklava, the only one on the south coast, believed fit for use as a base. How fateful and fatal was their choice the coming winter was to show. The French on the left established their base at Ka miesch. Scarcely had the armies got into position than St. Arnaud died, and the command passed to Canrobert, a soldier of high character and great personal charm, though to the English he "appeared with his gestures and grimaces like a play actor" ; a more serious defect was that he always thought so much was to be said on both sides of any question that he could never make up his mind which side had most to be said for it.

The fortifications of Sevastopol had been rendered formidable by Todleben, the chief engineer in the fortress, and ships sunk by the Russians in the harbour mouth rendered it difficult for the fleet to co-operate in the attack. The Allied bombardment opened on Oct. 17, but no assault followed, and a week later the Russian field army made its first essay at relieving the fortress by a sudden attack on the British right and rear aimed at Balak lava. Their onset was checked by a brilliant charge of the Heavy Cavalry Brigade but unfortunately in the first stage of the action some Turkish batteries were overrun and captured, and Raglan, faithful as ever to the tradition of Wellington who "never lost a British gun," sent orders by an aide-de-camp, Nolan, to the Light Cavalry Brigade to retake them. Nolan, who was a cavalry fanatic, and firmly believed in the omnipotence of that arm on the battlefield, so fulfilled his mission as to launch the brigade in quite a different direction—straight at the Russian artillery in position. The charge took place, one of the most heroic and use less episodes in English military history; and the battle ended, on the whole to the advantage of the Russians, who had cut the only good road between the British and their base at Balaklava. A few days later, on Nov. 5, another vigorous blow fell, this time at the junction of the British siege corps and their covering army on Inkerman heights. Thick fog veiled the field, prevented either Russian or Allied commanders from exercising such talents for generalship as they possessed, and reduced the battle to a pounding match between the soldiery. The aid rendered by the French proved invaluable at the crisis. The Russian masses ebbed sullenly back, and the armies settled down to a winter of siege warfare.

The horror, misery and suffering of that winter are, as regards the British, too well known to need detailed description here; Russell and other "low and grovelling" war correspondents with the army told the terrible tale in full in their despatches, and if, as the soldiers said, the information they gave was as useful to the enemy as any that an army of spies could have furnished, they aroused people at home to a belated realization of the fatal conse quences of sending out men to fight without taking forethought as to how they were to be fed, clothed, warmed and cared for. The French lost even more men from disease, but their more docile press was too effectively muzzled for any whisper of this fact to get out. The plight of the Russians was the worst of all; the sufferings of the garrison in Sevastopol and of the army in the field were terrible enough, but were as nothing to those of the unhappy recruits sent forward to the front from the interior ; two out of every three of these last named perished by the wayside of sickness or starvation.

The British situation, which became serious immediately after the loss of their supply ships in the great storm on Nov. 14, was rendered acute by the loss of the paved road from Balaklava to the army; it was said that of the 3,000m. from Plymouth to the British camp it was these last six that offered almost insuperable difficulties. Before the end of the year there were 8,000 men sick, and less than half the army was fit for service ; while the state of the hospitals was such as to increase rather than diminish the suffering of those who reached them and to tend to death rather than cure. It was not till the coming of Florence Nightingale— "the angel with the lamp"—that these hospitals attained some degree of efficiency, and it was not till the coming of spring, and with it ample supplies and necessaries from home, that the Brit ish force recovered something of its strength and again became fit for action. The construction of the "Balaklava tram" and a new paved road between the base and the army on the heights insured the latter against any repetition of the horrors of the winter months.

The spring, however, brought its own if rather different trials— if not to the armies, at least to their leaders—in the form of an electric cable which reduced the time of transit of correspondence between headquarters in the field and their respective capitals from ten days to 24 hours. The uses to which either nation put this new facility of intercommunication were significantly differ ent ; Napoleon III., for whom, as Prince Napoleon acutely re marked, military failure meant not, as in England, merely the doubtful drawback of a change of ministry, but the serious pros pect of a change of dynasty, showered advice, instructions and suggestions upon his commander-in-chief ; the British War Office on the other hand concerned itself more with enquiries as to the health of Capt. Jarvis, believed to have been bitten by a centi pede, and a heated discussion as to whether beards were an aid to desertion. It was small wonder that Gen. Simpson, Raglan's successor, was kept at work answering correspondence from 4 A.M. to 6 P.M. daily, or that he expressed the view that the tele graph had "upset everything." Meanwhile siege operations, which had continued spasmodically throughout the winter, were actively resumed with the coming of finer weather in April. Tsar Nicholas was dead, the disgrace ful failure of a Russian attempt to retake Eupatoria had broken his heart, and the chill hand of "Gen. Fevrier turned traitor" had stricken him into a welcome grave. His successor, however, was no less resolved to continue the struggle; and the attention of the Allied ministers and generals, which should have been concen trated on pushing forward with the siege, was now side-tracked into an attempt to thwart a sudden new plan, conceived by Na poleon III., for a campaign in the field against the main Russian host, to be undertaken by a new army under his personal com mand. This scheme met with universal discouragement and re monstrance, but it was late summer before its aggrieved author finally abandoned it. Meanwhile the Allied leaders had fallen out over a proposal for a joint expedition to Kertch, the Russian base in the eastern Crimea; Raglan desired it, Canrobert agreed to it, then, on remonstrance from Paris, thought better of it, and re called his troops. Mutual recrimination ensued ; Raglan declined to discuss any more subsidiary enterprises, and Canrobert wisely resigned the chief command and returned to the head of his own corps.

His successor, Pelissier, was a free-spoken, tough, resolute sol dier who knew his own mind and feared nobody and nothing. At his suggestion it was agreed to send out another expedition to Kertch, which met with complete success, and also to attempt the assault of Sevastopol on the anniversary of Waterloo, which met with an equally complete failure. One result of this last event was a change in command both on the British and Russian side ; Todleben, the soul of the defence, was severely wounded ; Raglan, now a weary and disappointed man, fell sick and died, regretted by all who had known him. His chief of staff, Simpson, succeeded him; shortly after his accession to command the Russian field army made a last and unavailing attempt to break the investing ring at the Tchernaya—a battle most noteworthy as giving Pied mont, who had joined in on the Allied side chiefly because her prime minister, Cavour, saw in it a means of publicity for a new power, an opportunity for achieving her war aims. Meanwhile Pelissier was growing weary of being the recipient of incessant strategical disquisitions from Paris, and became more and more curt with his self-constituted counsellors, the emperor and Mar shal Vaillant, as also with Niel who, as a missus dominicus of Na poleon, had been sent to the Crimea to keep him in leading strings. In the end he sought, but was refused, permission to resign the command, which he stated to be "impossible to carry on at the paralysing end of an electric cable." Eventually the atmosphere was cleared, thanks to the good sense of Vaillant, who first held up and afterwards secured the withdrawal of a somewhat intem perate letter of censure from the emperor, and Pelissier was let go his own way. On Sept. 8 a final assault on Sevastopol was de livered; the English attack on the Redan failed, but the French, assaulting at the hour of relief of the trench garrison, established themselves in the Malakoff. The fate of Sevastopol was sealed, and the Russians withdrew from their works to the north side of the harbour; none thought of pursuing them, and when Simpson, in explanation of this inaction, declared that he must wait to know the Russian plans, Queen Victoria wrote that she "was tempted to advise a reference to St. Petersburg for them." Simpson re signed, and Codrington, though junior to Colin Campbell, took his place ; but there was little more fighting to be done. The cap ture of Kinburn finally convinced Russia of the hopelessness of continuing the struggle; Napoleon had grown weary of the war; and though Britain, smarting under the memory of her inglorious share in the final assault on Sevastopol, would willingly have con tinued the campaign, she was not prepared to do so alone. The war therefore faded gradually into peace, and the Treaty of Paris, signed in Feb. 1856, had as sole tangible result the exclusion of Russian warships from the Black sea—and even this endured only for 15 years.

As far as concerns the military art, the Crimean War is usually regarded as worthy of remembrance only as perhaps the most ill managed campaign in English history, and a standing example of the difficulties and dangers of a coalition war. Yet from a broad point of view it may well be regarded as a highly creditable feat of arms on the part of the Allies. An expeditionary force of never more than 200,000 men, composed of troops of different nationali ties and under divided and incompetent leadership, was yet able to set foot on the territory of an enemy immeasurably superior in every resource of war ; to rend from his grasp a strong fortress, the possession of which was vital to the pursuit of his chosen policy; and to inflict on him during the struggle losses amounting to more than double its own strength. History affords no more striking demonstration of the range and potency of armies based on sea power—a demonstration which for Great Britain at least must always hold a lesson of permanent value. (F. J. Hu.; E. W. S.) W. Kinglake, The Invasion of the Crimea, ed. G. S. Clarke (1863) ; W. H. Russell, The War in the Crimea 56) ; A. Lake, The Defence of Kars (1857) ; E. B. Hamley, The War in the Crimea (1891) ; Evelyn Wood, The Crimea (1895) ; D. Lysons, The Crimean War from First to Last (1895) ; G. Lytton Strachey, Eminent Victorians (1918) ; P. Guedalla, Second Empire (1922) ; F. J. Huddleston, Warriors in Undress (1925). French: Official, Guerre de l'Orient, Hist. de l'artillerie (1859) ; Siege de Sebastopol, official account of engineer operations (1858) ; C. de Bazancourt, L'Expedi tion de Crimee (1856) ; C. Rousset, Histoire de la Guerre de Crimee (1877) ; G. Bapst, Marechal Canrobert, 6 vols. (1898-1913) ; J. F. Revol, Le Vice des coalitions: le Haut Commandement in Crimee (1923). Russian: F. E. I. Todleben, Die Vertheidigung von Sebastopol (1864) ; Defence de Sebastopol (1863) ; E. Bogdanovitch, Der Orient krieg (1876) ; A. N. Petroff, Der Donau Feldzug Russlands gegen Tiirkei, Germ. trans. (1891) . German: H. Kunz, Die Schlachten and Kampen des Krimkrieges (1889) ; Der Feldzug in der Krim (Leipzig, 1855-56).