Crucible Cast Steel

CRUCIBLE CAST STEEL. The crucible process, the oldest of the four leading methods for the manufacture of steel, and one which holds the premier position for quality, came into use in 1870 as the result of experiments by Benjamin Huntsman, who attempted to modify the irregularity of the imported blister steel or converted bar, and ultimately succeeded by melting the steel in crucibles.

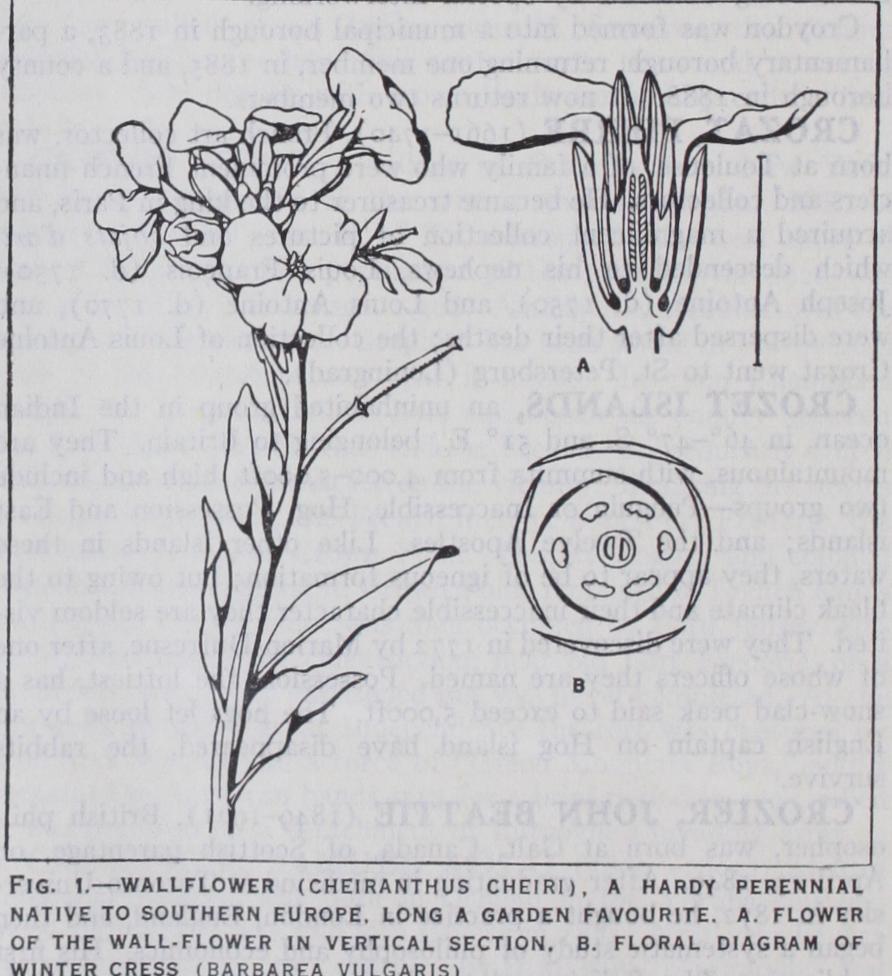

The furnace used for melting, a sketch of which is given in fig. I, is of very simple construction, and consists of a more or less elliptical melting chamber about 3 f t. 6in. deep, 2 f t. 6in. from front to back and 'ft. 6in. wide, lined with fire-brick and rammed ganister, and large enough to hold two crucibles. The top of the furnace is level with the melting-house floor, and is closed by a loose fire-brick cover. Under the melting-house is a vaulted cellar through which access is gained to the fire-bars and ash-pit of the furnace. The upper part of the furnace is connected by a short horizontal flue with a tall chimney about 4oft. high. The melting house is so arranged that the furnaces occupy two sides of the building leaving the centre free for the casting operation.

The Crucibles.

Either clay or plumbago crucibles may be used; for the production of castings the latter are preferred on account of their somewhat greater durability, but in the case of tool steel, where the content in carbon must lie between narrow limits, clay crucibles are almost exclusively employed.Before lighting up, any clinker adhering to the furnace walls must be removed. These precautions having been completed, fire clay stands, slightly less in diameter than the bottoms of the crucibles and about Sin. thick, are placed on the fire-bars, and crucibles, which have been grad ually heated up overnight in an annealing furnace, are placed on them. Ignited coke from the an nealing furnace is now spread over the fire-bars, and, when the fire is well alight, coke is added until it is level with the tops of the crucibles.

By the time this fire has burnt down, the crucibles will be at a white heat ; in the case of hand made crucibles a handful of sand must be thrown into the crucible to fill up the hole in the bottom.

The charge is now introduced through a charger—a wrought iron funnel long enough to reach from the mouth of the crucible to the top of the furnace-lids placed in the crucibles, and the furnace filled with coke to a point well above the covers of the crucibles.

When this fire, which is known as the first or steeling fire, has burnt down, which takes from 4o to so minutes, the furnace is again filled with coke and allowed to burn down a second time. The melter then examines the charge in the crucible to ascertain whether the whole of the charge is melted; if so, the third or killing fire is added. The fire is necessary to expel dissolved gases from the steel, which, if not removed would give rise to cavities, technically known as blowholes, in the ingots. When everything is deemed satisfactory by the melter, he instructs his assistant, "the puller out," to get ready for casting. The crucible lids are taken off, the slag removed from the surface of the metal, the crucibles with drawn from the furnace, and their contents poured into ingot moulds; these are rectangular in section, and are generally made of cast-iron, in two separate halves, held together by wrought iron rings and wedges, to facilitate the removal of the ingot. Imme diately after casting the crucibles are cleared of adhering clinker and returned to the furnace ready for the next charge. The first charge generally takes from five to six hours, and succeeding charges from two and a half to three hours.

Such is the method as originally devised by Huntsman; later it was found that the third or killing fire did not remove entirely the dissolved gases from the steel, and that chemical aid was nec essary; this was provided by the addition of ferro-manganese an alloy of iron and manganese containing about 8o% of man ganese—to the charge before applying the third fire. Aluminium may also be used for this purpose, but although somewhat more active in removing the dissolved gases (the third fire in many cases not being necessary), it is held by many that the ingots are not so clean as when manganese is used, and that they are more difficult to weld. Most often a combination of the two methods is employed, manganese additions being made with the third fire, and a chip of aluminium added just before casting.

Nature of Process.

The process is not essentially a chemical one, but slight changes in composition do take place. The silicon in the steel will be about double, and the manganese half, of what would be expected from the mean composition of the charge. This arises from the fact that part of the manganese is oxidized to man ganous oxide. and this reacts with the silica in the walls of the crucible, forming a manganous silicate slag from which silicon it reduced by the carbon in the steel. The sulphur will also tend to increase, due to absorption from the furnace gases, the amount of such absorption depending on the purity of the coke with regard to this element. With a sulphur content of 2% in the coke, the in crease of this element in the steel will amount to •oi %.Modifications of the method are used extensively. Instead of starting with blister steel, advantage may be taken of the affinity of molten iron for carbon, by melting bar iron in contact with sufficient carbon to give steel of the required hardness; or wrought iron and white cast-iron may be melted together. Whatever method is employed, however, it is of the greatest importance to see that the proportions of silicon and sulphur in the raw materials are sufficiently low to allow for the increases in these elements which occur during the process.

The desire to obtain more rapid melting and a lower consump tion of fuel than is possible in the natural draught furnace, has led to the application of forced draught to the ordinary coke-fired furnace, and to the use of furnaces specially designed for the use of producer gas, water gas, natural gas or oil. These furnaces generally possess a greater capacity than the Huntsman type, and may contain from four to 5o crucibles at one time. Although the quantity of steel contained in a single crucible is only small (so to ioolbs.), it is possible to utilize the process as a step in the manu facture of quite large forgings, by combining the contents of sev eral crucibles in a common ladle prior to casting. By this means ingots weighing as much as 8o tons have been produced.

As the process is simply a means of obtaining a steel with the average composition of the materials charged into the crucible, practically any grade of steel can be produced, but it is in the manufacture of high grade tool and cutlery steels that it finds its chief application. Of late years, especially in countries where elec tric power is cheap, it has found a serious rival in the electric furnace.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Sir

R. A. Hadfield, "The Early History of Crucible Bibliography.-Sir R. A. Hadfield, "The Early History of Crucible Steel," Journal of Iron and Steel Institute, vol. ii. (1894) ; D. Carnegie and S. C. Gladwyn, Liquid Steel (end ed., 1918) ; F. W. Harbord and J. W. Hall, The Metallurgy of Steel (7th ed., 1923). (T. BA.)