Cruiser

CRUISER. A fast and well-armed warship, specially designed for two main functions: (a) to guard the sea routes, (b) to act as an advance guard or scouting force for the battle fleet.

The first traces of that elaborate classification of warships into types with distinctive functions which is characteristic of the modern fleet can be discovered in the second half of the 17th century. Before that time fleets were not formed for action upon any generally accepted principle ; warships of all types and sizes took part at the same time and the action resolved itself into a series of isolated combats as the separate units found oppor tunity. The Queen's ships under the command of the Lord High Admiral operating against the Spanish Armada ranged from the "Triumph" of 1,10o tons to the "Signet" of 3o tons.

In the naval war of 1652 the Dutch fleet fought to protect convoys or to clear the seas for merchant traffic. It was as if the German battle fleet had made its way out of Kiel during the World War to engage the British fleet, so that a vast convoy of German merchantmen might slip safely away with their car goes. Dutch trade suffered to so great an extent that in subse quent wars of the period the Dutch merchant ships were with drawn to port, while the Dutch fleet endeavoured to secure permanent command of the seas. Thus the primary duty of a fleet came to be regarded as that of seeking out and destroying the enemy.

About the same time, the growing use of the fireship (there were 87 such ships working with the British Navy of 123 warships in 169o-17m) formed a pressing reason for developing the "line of battle": that formation by means of which, by opening their intervals, the fleet could best avoid fireship attack. The line of battle necessitated uniformity of sailing and gun power in order to be effective, and large offensive power per vessel so that the line should not be too long. These requirements pre cluded the employment of the smaller warships of the day in the line. On the other hand, the breaking up of convoys into smaller and less valuable groups, withdrew from the capital ship the temptation to make the capture of these her objective and opened opportunities both of attack and defence for the smaller fight ing ships.

Developments were of slow growth, but by the middle of the 18th century the line of battleship, the frigate, a faster and more lightly armed vessel to act as observer for the line of battleship, but not to occupy a place in the line, and the light cruiser, a still more lightly armed vessel for commerce protection, were accepted types. The principles of sea warfare, which brought these types into being, have not always been clearly recognized, but war has inevitably brought them into prominence.

At the beginning of the Napoleonic wars there was considerable heterogeneity of type both among battleships and frigates, but by the closing years the main battle fleet was composed almost entirely of 74-gun ships (85 out of 99 capital ships), the many classes of frigates were in course of replacement by a uniform type of 38 and 36-gun ships, and there were 403 ships of below 20 guns out of the 55o cruising ships of the Navy required for convoy and look-out duties, and this notwithstanding the un challenged command of the sea which the main fleet had obtained.

It is also possible to trace the gradual standardization of types after the wooden and sailing Navy had given way to more mod ern construction. Cruisers, to use the general term, gradually came to be grouped into four fairly well defined classes :—the battle cruiser; the armoured cruiser; the protected cruiser, and the light cruiser. The first of these may be regarded as the cul minating point of cruiser design.

Battle Cruiser.

The development of the armoured cruiser with 9-in., or, in the case of Japan, even i2-in. guns, seemed to call for a new type of warship, one faster than any class afloat except the destroyer, and with an armament second only to that of the battleship. This resulted in the battle cruiser, the first example of which was the "Invincible" class, contemporaries of the improved "Dreadnought" class of battleship. (See Tech nical section of this article.) It was conceived that a squadron of such ships would be able to drive in the enemy's cruiser forces, unmask his battle fleet and harry the latter's van and rear during the main action.Battle cruisers were not originally intended to engage in pro longed duels with ships of their own class, as they actually did in the Dogger Bank action and in the preliminary stages of Jut land (q.v.). For such "hammer and tongs" fighting they, as a class, and the British design in particular, were not well suited and the latter suffered accordingly; but the fact that the World War found Germany with a powerful battle cruiser fleet, made such engagements almost inevitable, particularly in the low visi bility which so often prevails in the North Sea.

The most striking success of the battle cruiser as a type was that achieved by the two British ships at the battle of the Falkland Islands (q.v.), but there they were overwhelmingly superior to their opponents in speed and in the range and calibre of their guns ; moreover, the weather conditions gave them every oppor tunity to make the most of their advantages. There, too, they filled a role which was unforeseen when they were designed ; viz., that of making a sudden descent on an enemy cruiser force in dis tant seas. Nevertheless, they were most effective in it, thanks to the master-hand of the man who was chiefly responsible for their conception—the veteran First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher. The secrecy and promptness with which they were despatched, the timely arrival of a force so powerful that it left nothing to chance, formed a striking example of correct and vigorous strategy.

The Washington Treaty (q.v.) having limited the amount of capital ship tonnage, it seems probable that the sea powers will prefer to make use of their respective quotas for battleship construction only, in which case the battle cruiser as a type will gradually die out ; in fact, with the extinction of the German battle cruiser fleet, Britain and Japan are the only two nations whose navies include this type of warship, which was not adopted by any of the other great sea powers.

Armoured Cruisers.

The heavy armoured cruiser, such as the "Defence" class, has become practically extinct. It did not prove of much value in the World War. Too slow, as compared with the modern battleship, it was not a useful auxiliary to the battle fleet, it could not face the enemy battle cruisers, while it was needlessly costly and unsuitable in other ways for guarding the trade routes. At Jutland the British armoured cruisers suf fered heavily and could be of very little service.

Protected Cruisers.

The term has now died out, but ships of this type, such as the "Amphitrite" class, were representative of the ocean-going, commerce-protecting cruiser of their time, and the forerunners of the io,000-ton cruiser of to-day.

Light Cruisers.

As the place of the big cruiser was taken by the armoured cruiser and eventually by the battle cruiser, and with the growing size and power of the destroyer, there came an ever-increasing demand for light, fast cruisers to act as fleet auxiliaries. As the World War went on, this type became more and more numerous and produced a more or less standard design of "fleet cruiser"—ships of about 3,500 to 5,000 tons, armed with six-in. guns. The type was chiefly intended for work in the North Sea and since the War has not proved adequate to replace older and much larger ships required for high-sea work, but long since worn out and scrapped.Some years after the War, the British Admiralty decreed that, in future, there would be only two categories of cruisers—the "battle cruiser" and the "cruiser"; but, in fact, the latter category was still in 1928 divided into the large cruiser and the small cruiser, known as "A" and "B" classes.

The Washington Treaty, although in no wise affecting total cruiser tonnage, limited the size of these warships to io,000 tons, and their armament to 8-in. guns. This has produced a tend ency among the sea powers to design new ships up to these maxi mum dimensions, and, therefore, perhaps, to induce them to build bigger ships, in some cases, than they might otherwise have done. This is not altogether to be wondered at ; with the object lessons of the battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands in mind there should he a disinclination to send ships to distant stations if they are so weak or so small as to be at the mercy of a potential enemy. At the same time, it is questionable whether somewhat smaller cruisers would not be adequate for much of the work they are required to do. A proposal to limit the number of 10,000 ton cruisers put forward by Great Britain at the Naval Conference at Geneva in Aug. 1927 was opposed by the United States, that nation maintaining that, because of the great distance existing between her naval bases, small cruisers, unable to carry supplies for a long voyage, were ineffective. Great Britain has continued to build light cruisers chiefly while those planned in the United States are of the heavy type.

To the British Empire, scattered all over the world and knit together by the long sea routes, the question of cruisers is a vital one. The very life and sustenance of the inhabitants of the Brit ish Isles depend on these sea arteries being secure throughout their entire length. This can only be ensured by a sufficiently large number of cruisers to police them; but such a force, with its units widely distributed, as they always are and must be, does not constitute a menace or challenge to other nations; for it could only be concentrated into one large fleet at the risk of exposing the sea arteries to being severed at many distant points. This would cause the dismemberment of some parts of the Empire, while the heart would be starved of some vital commodity.

Nelson and many another old-time sea commander complained bitterly of the lack of frigates. At the beginning of the World War, Britain had more than double the number of cruisers she possessed in 1928, yet the Admiralty were at their wits' end for ships of this class.

To-day the cruiser, as a type, stands for security for those of all nations who "pass on the seas on their lawful occasions"; they are the safeguards of civilization lest it should be assailed by the many wild and uncontrolled forces which still abound in and around the waters of the world. But for the cruisers of the various sea Powers, piracy, gun-running and slavery would be rampant again. In fact, the cruiser should be respected and maintained as a powerful factor in preserving peace and tran quillity the world over. (E. A.) The progress in technical science, which marked the opening years of the 19th century and has continued without pause for more than a hundred years, gave to the naval constructor iron for wood (1850-60), steel for iron (1877), the screw the turbine (1902), the geared turbine (1914), the rifled gun (1865), the breech loader (188o), barbettes securing exten sive arcs of fire (188o), wrought iron armour (186o), and ce mented armour (1900). Corresponding changes took place in the character and construction of warships, but the broad principles of the functions of the cruising type, as of the battleship (q.v.), remained unaffected.

During the interval within which these scientific developments were becoming accessible there was naturally considerable diver sity in design, and among the cruising vessels on active service were frigates, corvettes, 2nd class cruisers, despatch vessels and torpedo cruisers, sloops and gun vessels. It was not until the British Naval Defence Act of 1889 that types of present-day cruisers came into being; when the ships built under this Act were completed in 1892, cruisers were arranged in first, second and, third classes; type ships being "Blenheim" (1890) of 9,000 tons displacement, speed 202 knots, armed with 2 9.2in. and io 6in. guns, with a protective deck 3 inches thick; "Apollo" class (1891), of 3,40o tons displacement, speed 20 knots, armed with 2 6in. and 6 4.7in. guns with a protective deck I in. thick; and "Philomel" (1890), of 2,575 tons, 19 knots, armed with 8 4.7in. guns, with a protective deck 1 in. thick.

The "Blenheim" type continued till 1898, when the "Diadem" class of II,000 tons and 21 knots were the last of the large cruisers protected only by a thick deck. The "Apollo" type con tinued until they were displaced by the armoured cruiser and the light cruiser, the last class being "Chatham" (191 i) of 5,40o tons displacement, speed 251 knots, which ship had a Sin. nickel steel belt amidships, in addition to the protective deck. The "Philomel" type ended with the "Amphion" class (I 9 ' I ), of 3,44o tons dis placement and speed 251 knots, after which they merged into the light cruiser type.

The Armoured Cruiser.

The introduction of Harveyised armour, enabled armour only 6in. thick to provide very sub stantial protection to the sides of cruisers, which was first taken advantage of in the "Cressy" class (1901) , which vessels were the forerunners of both the armoured and battle cruisers. The ships were of 12,000 tons displacement, speed 2I2 knots, armed with 2 9.2in, and 12 6in. guns and two submerged torpedo tubes.They had a protective deck of 2-3in. thick and side armour 6in. thick. The types passed through several stages until the "Mino taur" (1905) of 14,00o tons, 23 knots, armed with 4 9.2in. and Io 7.5in. guns and five torpedo tubes.

The Light Cruiser.

The "Arethusa" class were the first ves sels of this new type of fast lightly armoured cruisers. Their dis placement was 3,50o tons and speed 29 knots. The machinery was of 40.00o s.h.p. and was the same as in the L class de stroyers. They were the first cruisers to burn oil fuel only. The armament was 2 6in. and 6 4in. guns, and the side had protective plating 3-2in. thick. The following classes, "Calliope" and "Dance," were similar in many respects but embodied important improvements, geared turbines in "Champion" and later vessels, while in the later "C" class vessels and in the "D" class, a uniform armament of 6in. guns all mounted on the middle line, gave each vessel a powerful broadside. The "Emerald" class followed in 1917, the speed being increased to match the high speed of the German cruisers then building. Machinery of 8o,000 s.h.p. was fitted. The displacement was 7,50o tons, speed 33 knots, and they were armed with 7 6in. guns and 12 2 I in. torpedo tubes.

The Ocean Cruiser.

The cruisers of the war period were of a type suitable for service in the North Sea, but in 1915 designs were prepared for the "Raleigh" class, more especially suited for ocean work in any part of the world. They have a speed of 30 knots and are armed with 7 7.5in. guns, five of which are on the middle line and two, one on either side, amidships. They are adapted for burning coal and oil. The Sin. belt of earlier vessels is repeated and in addition they are bulged against torpedo attack.

The Battle Cruiser.

The 1904 Committee on Designs, which produced the "Dreadnought" also recommended a new type of cruiser which has been designated a battle cruiser, the same calibre of guns being mounted as in battleships. The overruling con sideration was speed, therefore it was necessary to surrender a certain number of guns and a great deal of armour as compared with the battleships.The first ships of this type were "Invincible," "Inflexible" and "Indomitable," S3oft. in length, 17,25o tons, 41,00o h.p., turbine machinery, quadruple screws and 25 knots speed. Eight 12in. guns were fitted in four turrets. The armour protection was on a 6-in. basis only.

Successive improvements were made in "Indefatigable," "Aus tralia" and "New Zealand" with increased displacement, and then the 28-knot ships "Lion" and "Princess Royal" were laid down in 1909-I0. The horse power rose to 70,00o and 8 13.5in. guns were provided, the displacement rising to 26,35o tons. The armour protection was on a gin. basis. The "Queen Mary" (191 I) was generally similar. Further improvement was made in the "Tiger" (1912), of 28,50o tons, in which ship 12 6in. guns were fitted in addition to the main armament of 8 13.5in. guns.

The success of the battle cruisers "Invincible" and "Inflexible" at the Falkland Islands battle led to the building of two fast cruisers, "Renown" and "Repulse," in lieu of two battleships of the "Royal Sovereign" class which had been laid down. These vessels had 6 15in. guns and 17 4in. guns and an armour belt of 6in. thickness. The machinery was virtually a repeat of that of "Tiger," and with 112,000 h.p. the "Repulse" obtained 32.6 knots on the measured mile trial. They were 75o ft. long, with a displacement of 26,50o tons and they carried 4,25o tons of oil fuel. The construction of these vessels in about 20 months from the initiation of the design constitutes a record in design and construction.

The "Hood" was designed as a battle cruiser in 1916 and during building the lessons of the Battle of Jutland were incorporated in the ship. The protection was brought up to battleship standard, the belt being 8-4 2in. and barbettes 9-12in., and the thickness of the protective deck was also considerably increased over pre vious ships. A bulge to provide protection against torpedo attack was also a part of the design. She was armed with 8 i5in. guns and 12 6in. guns. Geared turbines were adopted for the ma chinery, giving a total power of 144,00o s.h.p., and the ship attained 3 2 knots on her trials.

Germany in 1906 passed an act authorising an extensive build ing prc7amme of war vessels to be completed by 1917, which beside battleships and torpedo craft, included twenty large and thirty-eight small cruisers. A series of armoured and battle cruis ers was started, "Blucher," of 15,5oo tons displacement, speed 24 knots, armed with 12 8.2in. and 8 5•qin. guns and 4 i8in. torpedo tubes, being the first, followed by "Von Der Tann," "Moltke," "Goeben," "Seydlitz," "Derfflinger," "Lutzow" and "Hindenburg." They were all fast powerful vessels, and the last named had a displacement of 27,00o tons, speed 28 knots (85,000 s.h.p.), armed with 8 i tin. and 14 5.9in. guns and 4 19.7in. torpedo tubes, armour 7 in. thick on side, loin. on barbettes. For light cruisers, a continuous building programme of about 3 vessels per year took place, the vessels varying from "Dresden" class, tons displacement, 24 knots, armed with 4.sin. guns and 4 torpedo tubes, to "Köln" of 5,600 tons, 271 knots, armed with 8 5.9in. and 3 8.8cm. guns, and 4 torpedo tubes.

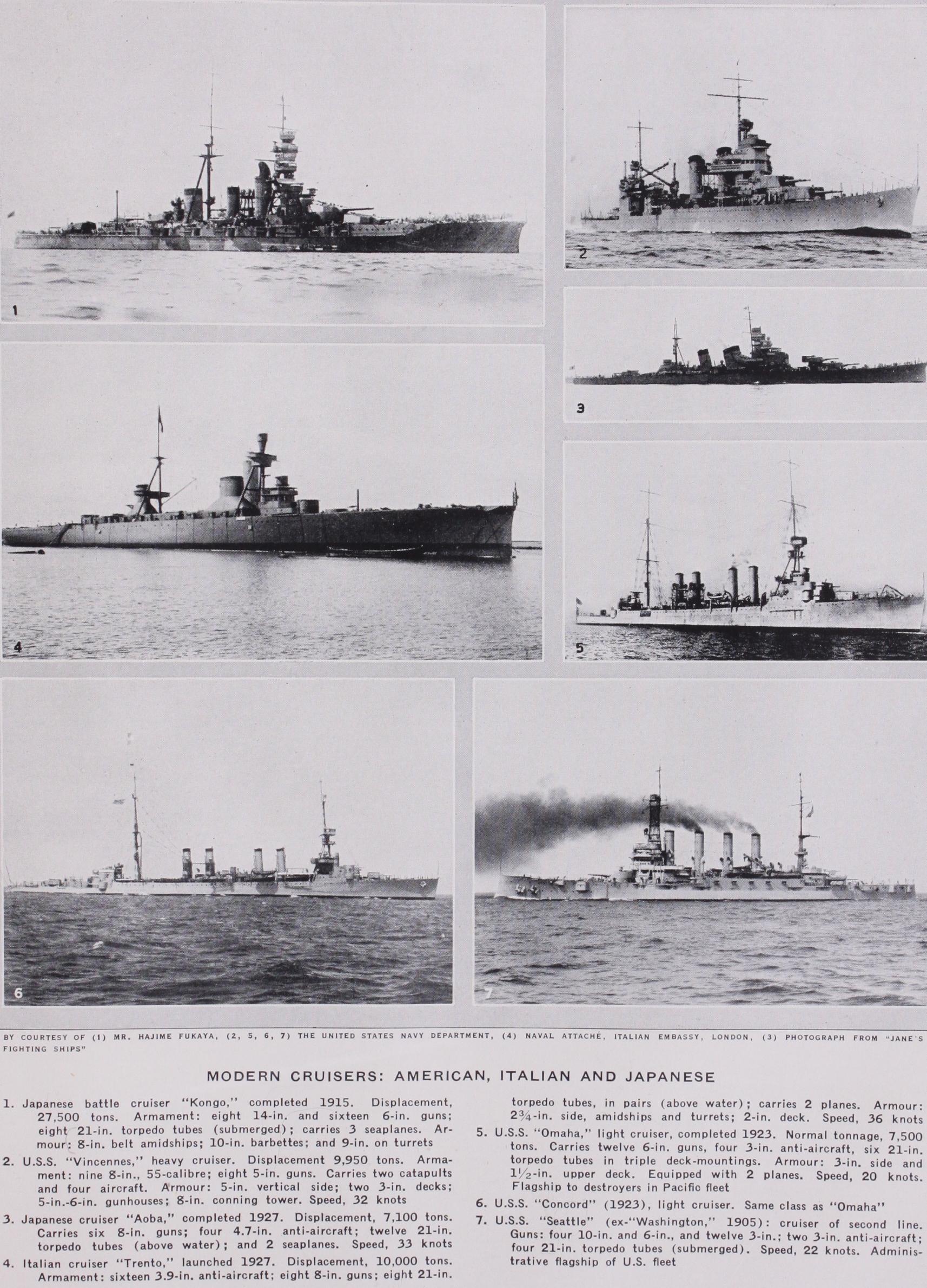

Japan was the only other nation to complete battle cruisers before the World War, with the "Kongo" class (4), 2 7, 50o tons displacement, speed 28 knots, armed with 8 14in. and 16 6in. guns and 8 2iin. torpedo tubes, completed in 1913. Her armoured cruisers completed after 1906 are the "Tsukuba" class (2) and "Kurama" class (2), the latter of 14,60o tons displacement and 212 knots, completed in 191 o. The last light cruisers completed before the war were the "Yahagi" class (3) of 4,95o tons and 26 knots, armed with 8 6in. and 4 3in. guns and 3 i8in. torpedo tubes. Since the World War about 14 fast light cruisers have been built of about 5,50o tons displacement, 33 knots, armed generally with 7 5.5in. guns and 6 or 8 2iin. torpedo tubes. Also the "Furutaka" class (4) (see P1., fig. 3), which vessels are of 7,500 tons displacement, 33 knots (Ioo,000 s.h.p.), armed with 6 8in. and 4 4.7in. guns and 12 2iin. torpedo tubes.

The United States did not complete any battle cruisers, and in 1914 the latest armoured cruisers in the American navy were the vessels of the "Tennessee" class (4) (P1., fig. 7), completed about 1908, of 14,50o tons displacement, speed 224 knots, armed with 4 loin. and 16 6in. guns, and 4 21 in. torpedo tubes, and the "Pennsylvania" class (6), of 13,68o tons, 22 knots, armed with 4 8in. and 14 6in. guns and 2 i8in. torpedo tubes. Prior to the World War the "Chester" class (3), completed in 1908, were the newest light cruisers, but in 1916 the 1 o vessels of the "Omaha" class were authorised. These ships are of 7,50o tons displacement, 331 knots (90,00o s.h.p.), armed with 12 6in. and 4 3in. guns and 6 2iin. torpedo tubes.

France and Italy also did not build battle cruisers, but each had several classes of armoured cruisers completed after 1905. These were, for France, the "Waldeck Rousseau" class (2), the "Ernest Renan" (2), and the "Leon Gambetta" (2), the first-named ships being of 14,00o tons displacement, 23 knots, with a main arma ment of 7 6in. guns; and for Italy, the "San Giorgio" class (2) and "Pisa" class (2) . These vessels were of io,000 tons displace ment, 23 knots, and with a main armament of 2 or 4 loin. guns, 8 7.5in. guns and 3 i8in. torpedo tubes.

The Washington Agreement of 1921 fixed a limit of io,000 tons displacement for war vessels other than capital ships, and of 8in. for the gun mounted in such vessels. Since this conference, the five Powers concerned have each started building cruisers up to the limits allowed. Great Britain has completed the vessels of "Kent" class (5) and "London" class (4) , and has two vessels of "Dorsetshire" class under construction. The U.S.A. has under construction "Pensacola" class (2) and "Northampton" class (6), while orders have been placed for 5 vessels of the 15 authorised to be laid down 1928-1931. Japan has completed the "Nachi" class (5) and has under construction 5 vessels of "Takao" class. France has completed the "Duquesne" class (2) and "Suffren." Two more vessels of "Suffren" class were under construction in 193o. Italy has completed "Trento" class (2), and has under construction 4 vessels of "Zara" type.

These vessels are all designed to obtain speeds of more than 3o knots, and in some cases, by the deletion of any protective plating, very high speeds have been obtained. In general, they carry a main armament of 8 or so 8in. guns with anti-aircraft guns and torpedo tubes. The weakness of the type is the in sufficiency of protection that can be provided on the limited dis placement, but it is too soon to state what will be the ultimate influence exercised by this important type of ship upon cruiser design.

By the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was not allowed to exceed a cruiser displacement of 6,000 tons, and she has produced the "Emden," "Karlsruhe" class (3) and "Leipzig." The last ship has a speed of 32 knots and a main armament of 9 5.9in. guns in triple turrets. (W. J. B.) Note: Particulars regarding the cruisers of other nations as well as additional particulars regarding the navies of the different countries of the world will be found in the section headed Defence in the articles on the various countries, as United States, France, Japan, Italy, etc. To these the reader is referred.