Crustacea

CRUSTACEA, a very large division of the animal kingdom comprising the crabs, lobsters, crayfish, prawns, shrimps, sand hoppers, woodlice, barnacles, water-fleas and a vast multitude of less familiar forms that are not distinguished by any popular names. In systematic zoology they are ranked as one of the classes forming the phylum (or sub-phylum) arthropoda, (q.v.) and are distinguished from the members of the other classes by being generally of aquatic habits, breathing by gills or by the general surface of the body, having two pairs of antenna-like appendages in front of the mouth and at least three pairs of post oral limbs acting as jaws. There is so much diversity, both of structure and of habits, within the class, that it is all but im possible to give a brief definition which shall apply to all its mem bers, and all the characters men tioned are subject to modifica tion in parasites and other highly specialised forms.

It would not be altogether mis leading to describe the Crustacea as the "insects of the sea." In the great oceans and in the nar row seas their teeming multitudes, the "things creeping innumerable" of the Psalmist, play a part not unlike that taken by the true insects in the life of the land. In fresh waters, where they have to meet with the competition of insects, they are hardly less abundant and there is scarcely a ditch or pond that does not harbour at least some of the more minute forms. On land they are less common, but the woodlice of our gardens and the land-crabs of tropical regions have solved the problem of adaptation to a sub-aerial life.

The most familiar Crustacea are the larger crabs and lobsters which are used as food by man, but the part which these play in the economy of nature is small compared with that of the amphi pods and isopods which swarm in the shallower waters of the sea and serve as scavengers, feeding on all kinds of animal and vege table refuse and forming, in their turn, the food of many of the larger marine animals such as fishes. Vastly more important. than any of these, however, are the minute pelagic copepods, of which the shoals may discolour the surface waters of the ocean for many miles and serve to guide the fisherman and the whaler to the most profitable fishing grounds. They form an important constituent of plankton (q.v.), the assemblage of minute floating animal and vegetable life in the surface waters of the ocean. It is on the plankton that a great part of the higher animal life of the sea ultimately depends for food. The copepods live upon the diatoms and other microscopic plant life of the plankton and themselves form the food of many fishes such as the herring and the mackerel and even of the gigantic whales.

External Structure: Body.—As in all arthropods the firm outer covering or exoskeleton of the body consists of a series of segments or somites which may be jointed together or more or less coalesced. The typical form of a somite is seen, for instance, in the segments which make up the abdomen or "tail" of a lob ster or crayfish. Each consists of a shelly ring separated from the rings in front and behind by areas of softer integument forming movable joints. The arched plate which forms the dorsal part of the segment is distinguished as the tergum and the narrower ven tral bar as the sternum. The tergum is produced on either side as a free plate, the pleuron, and each segment has a pair of limbs articulated to the sternum. The posterior terminal segment of the body, on which the opening of the anus is situated, never bears typical limbs and is known as the telson. Its morphological nature is shown by its development. In the larvae of the more primitive Crustacea, the number of somites, at first small, in creases by the successive appearance of new somites between the last-formed somite and the terminal region which bears the anus. The "growing-point" of the body is, in fact, situated in front of this region, and, when the full number of somites has been reached, the unsegmented part remaining forms the telson of the adult. In no crustacean, however, are all the somites of the body distinct and separate from each other. The fore part of the body of the lobster, for instance, has an undivided shelly covering, the "barrel" or carapace, and the number of somites composing this region is only to be inferred from the appendages attached to it. In all Crustacea an anterior region is marked off by having the somites obscured in this way. Apart from the possible existence of an ocular somite corresponding to the eyes (the morphological nature of which is discussed below) the smallest number of somites so united in any adult crustacean is five. Even where a larger number of somites are fused there is generally a marked change in the character of the appendages after the fifth pair, and, since the integumental fold which forms the carapace seems to originate from this point, it is usual to regard these five somites as constituting the head or cephalon. It is quite possible, however, that in the primitive ancestors of existing Crustacea a still smaller number of somites were united in the head. The first three pairs of appendages are alone present in the "nauplius" larva, and they show certain peculiarities of structure and development that seem to place them in a different category from the other limbs. There is therefore some ground for regarding the three corresponding somites as forming a "primary cephalon." In the sub-class Malacostraca, which includes all the larger and better-known Crustacea, the body proper is divided into two re gions sharply distinguished by the character of the appendages. These are the "thorax" of eight somites and the abdomen. In the other sub-classes, although the terms thorax and abdomen are often used as descriptive terms, the regions so named are not homologous with those of the Malacostraca. In many of the lat ter, as, for example, in the lob ster, the head and thorax form a single undivided region which is known as the "cephalo-thorax." The shell or carapace covering this region is not simply formed by the coalesced terga of the somites. In some of the lower Malacostraca, such as the Mysi dacea, the carapace is a fold of the integument, enveloping, but remaining free from, the thoracic somites. In the lobster and other Decapoda, the carapace has coalesced with the thoracic terga in the middle of the back but remains free at the sides, enclosing a pair of chambers within which lie the gills.

The possession of this carapace, arising as a dorsal fold from the posterior margin of the head-region, is a character which re curs in the most diverse groups of the Crustacea and is probably to be regarded as a primitive attribute of the class. The carapace may have the form of a bivalve shell, entirely enclosing the body and limbs, as in many Branchiopoda and in the Ostracoda. In the Cirripedia it forms a fleshy mantle strengthened by shelly plates which may have a very complex structure. In the Isopoda and Amphipoda, where, as a rule, all the thoracic somites except the first are distinct, there seems at first to be no carapace-fold. A comparison with the related Tanaidacea and Cumacea, however, suggests that the coalescence of the first thoracic somite with the head really involves a vestigial shell-fold and this is possibly the case also in the Copepoda. The only Crustacea in which there appears to be no trace of a cara pace are the anostracous Bran chiopoda and the remarkable syn caridan Bathynella.

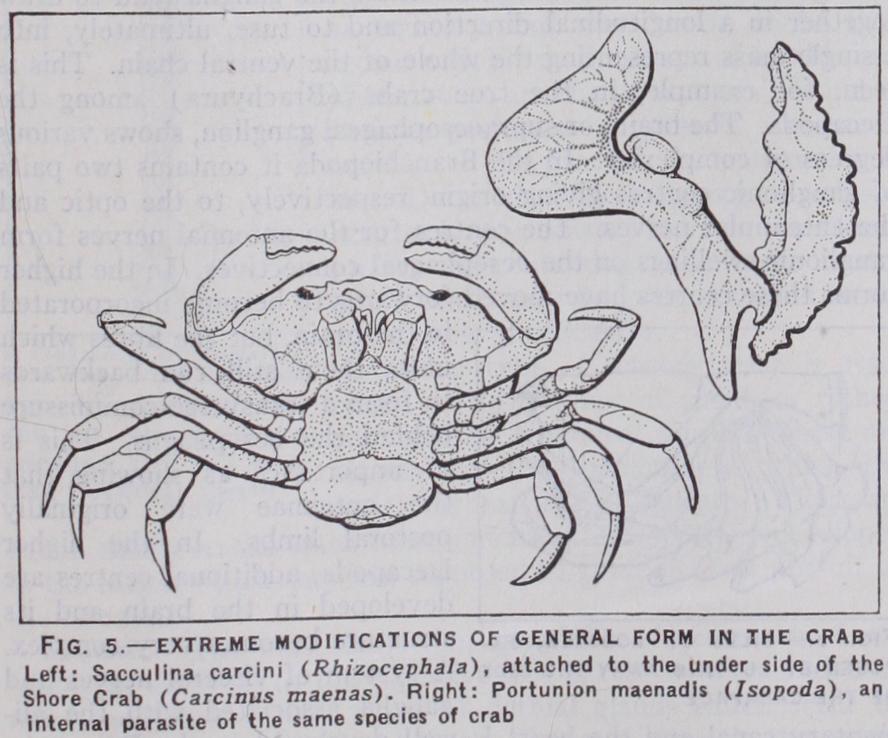

The most extreme modifications of the general form of the body are shown in those Crustacea which have adopted a sedentary or a parasitic habit of life. The Cirripedia or barnacles are, in the adult state, rooted to one spot by the head, and tend, in varying degrees, towards the radial sym metry which is often associated with a sedentary life. In parasites, the segmentation of the body tends to disappear and the general shape is often distorted in a fantastic manner. In the Rhizocephala, and other parasitic cirri pedes, the adults have lost nearly every trace, not only of crus tacean but even of arthropodous structure.

General Structure of Limbs.

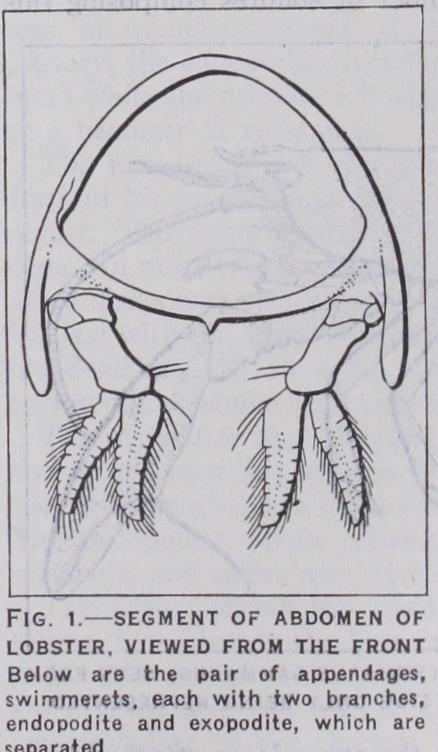

Amid the great variety of forms assumed by the appendages of Crustacea, it is possible to trace, more or less plainly, the modifications of a fundamental type consisting of a peduncle, the protopodite (or sympodite), bearing two branches, the endopodite and exopodite. This simple bira mous form is shown in the swimming feet of Copepoda, the "cirri" of Cirripedia and abdominal limbs of Malacostraca, and it is also found in the earliest and most primitive type of larva known as the "nauplius." The protopodite may have, on its inner and outer margins, additional lobes or processes, known as endites and exites respectively. Some of the exites often function as gills, and the endites of appendages near the mouth frequently form jaw-processes, assisting in mastication and known as gnathobases. In the flattened leaf-like limbs characteristic of the Branchiopoda the endites and exites are so developed that the biramous form of the limb is obscured. It has been supposed that this form of limb, the "phyllopodium," represents the primitive type from which the biramous type has been derived. The recurrence of the biramous type, however, in the most diverse forms of Crustacea and in the simplest larvae, and the evidence of the remarkable fossil branchiopod Lepidocaris, all go to show that it represents the fundamental plan of the crustacean limb.

In

many Crustacea the paired eyes are borne on stalks which are movably articulated with the head and may be divided into two or three segments. The view has been held that these eye stalks are really limbs, homologous with the other appendages. The evidence of embryology, however, is decidedly against this view. The stalks appear late in the course of development, after many of the trunk-limbs are fully formed, and the eyes, at their first appearance, are sessile on the sides of the head and only later become pedunculated. The most important evidence in favour of the appendicular nature of the eye-stalks is found in the fact that when the eye-stalk is removed from a living lobster or prawn, a many-jointed appendage like the flagellum of an antenna may grow in its place. It is open to question, however, how far the evidence from such "heteromorphic regeneration" (see HETERO MORPHOSIS ; REGENERATION) can be regarded as conclusive on points of homology.

Special Morphology of Limbs.

The antennules (or first antennae) are generally regarded as true appendages, although they differ from all the other appendages in the facts that they are always innervated from the "brain" (or preoral ganglia) and that they are uniramous in the earliest and in the adults of all sub-classes except the Malacostraca, where they are biramous or sometimes triramous. It is unlikely that the two branches of the biramous type (seen, for instance, in the antennules of the lobster) correspond to the endopodite and exopodite of the other limbs.

The antennae (or second antennae) are of special interest on account of the clear evidence that, although preoral in position in all adult Crustacea, they were originally postoral appendages. In the "nauplius" larva they lie at the sides of the mouth and their basal portion carries a hook-like process which assists the similar processes of the mandibles in pushing food into the mouth.

In most Crustacea the antennules are purely sensory in function and carry numerous "olfactory" hairs. They are used as swim ming organs in many larvae and some adults, and sometimes, in the male sex, they form clasping organs for holding the female. In the Cirripedia the antennules of the larvae carry the openings of the cement glands and become, in the adult, involved in the attachment of the animal to its support.

The antennae are frequently swimming organs, but may assume other functions as organs of attachment in parasites, as creeping legs, or as male claspers. In the Malacostraca they are chiefly sensory, the endopodite forming a long many-jointed lash (flagel lum) while the exopodite is often a flattened plate, probably used as a balancer in swimming.

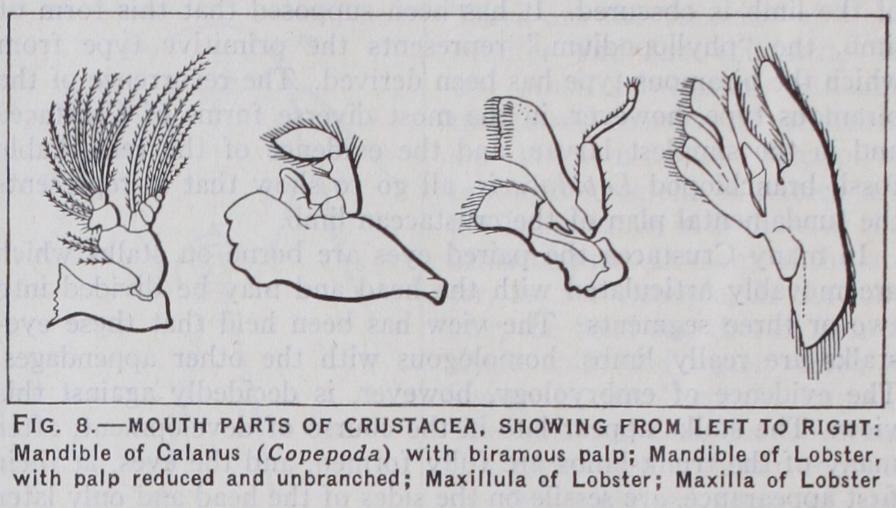

The mandibles, like the antennae, have, in the nauplius, the form of biramous swimming limbs, with a jaw-lobe on the proto podite. This form is retained in some adult Copepoda and Ostra coda. In most cases, however, the palp loses its exopodite and it often disappears altogether, and the basal lobe becomes a power ful jaw with the edge variously armed with teeth and spines. In blood-sucking parasites the mandibles are often piercing stylets enclosed in a tubular proboscis formed by the upper and lower lips.

The maxillulae and maxillae, or, as they are often called, first and second maxillae, are nearly always flattened leaf-like append ages with gnathobasic lobes or endites borne by the protopodite. The endopodite, when present, forms a palp of one or a few segments, and exites may also be present.

The limbs behind the head-region show little differentiation among themselves in the Branchiopoda, Cirripedia and many Cope poda. It is characteristic of the Malacostraca that the trunk-limbs are divided into two sharply-defined series or "tagmata," eight corresponding to the thoracic and six to the abdominal region. The thoracic series have the endopodites converted, for the most part, into more or less efficient walking-legs, while the exopodites are swimming organs or disappear. It is usual for one or more of the anterior pairs to be modified as "foot-jaws" or maxillipeds. The abdominal limbs are usually biramous and natatory, the last pair being large and flattened and forming with the telson a lamellar "tail-fan." Gills.—In many of the smaller Crustacea no special gills are present and respiration is carried on by the general surface of the body and limbs. When gills are present they are generally formed by some of the exites near the base of the limb, which are flat tened, thin-walled, and permeated by a network of blood-channels.

In the Decapoda the gills are inserted, in three series, at or near the bases of the thoracic limbs, and lie within a pair of branchial chambers covered by the carapace.

Adaptations for aerial respiration are found in those Crustacea that have taken to terrestrial life. In the land-crabs (of several different families) the branchial chambers are enlarged and serve as lungs, the lining membrane being richly supplied with blood vessels. In some of the terres trial Isopoda or woodlice the abdominal appendages contain tufts of branching tubules filled with air, like the tracheae of insects and other t err e s t r i a l Arthropoda.

Internal Structure: Ali

mentary System.—In almostall Crustaceae the f ood-canal runs straight through the body, except in front where it curves down wards to the ventrally placed mouth. In a few cases its course is sinuous or twisted and in one or two instances (Cladocera, Cuma cea) it is actually coiled upon it self. As in other arthropoda, it consists of three divisions, the fore-, mid- and hind-gut, the first and last being lined by an inturn ing of the chitinous cuticle. In the Malacostraca, the fore-gut is dilated to form a so-called "stom ach," furnished internally with ridges armed with spines and hairs forming a straining appa ratus. In the Decapoda this ap paratus reaches its greatest com plexity, forming a "gastric mill" in which three teeth connected with a system of articulated ossicles are moved by special muscles so as to triturate the food which is passed into the stomach.The mid-gut is essentially the digestive and absorptive region of the alimentary canal and its surface is, in nearly all Crustacea. increased by pouch-like or tubular outgrowths which not only serve as glands for secretion of the digestive juices, but aid in the absorption of the digested food. In the Decapoda these outgrowths form a massive digestive gland or "liver." In some decapods, as, for instance, in the crayfish, the mid-gut is very short, nearly the whole length of the food-canal being formed by the fore and hind guts. In a few highly modified parasites the alimentary canal is vestigial or absent throughout life.

Circulatory System.

As in the other Arthropoda, the cir culatory system in Crustacea is largely lacunar, the blood flowing in spaces or channels without definite walls. The heart is of the usual arthropodous type, lying in a pericardial blood-sinus with which it communicates by valvular openings or ostia. In most Branchiopoda and in some Malacostraca the heart retains more or less completely the primitive form of a long tube, extending throughout the greater part of the length of the body and having a pair of ostia in each somite. In most Crustacea however, it is shortened and gives off one or more main arteries which carry the blood for some distance to pour into the blood-spaces of the body. In many of the smaller Crustacea there is no heart, and it is impossible to speak of a circulation in the proper sense of the word, the blood being merely driven hither and thither by the movements of the body and limbs and of the alimentary canal.

Excretory System.

The most important excretory or renal organs of the Crustacea are two pairs of glands lying at the base of the antennae and of the maxillae respectively. The two are rarely functional together, although one may replace the other in the course of development. In the adult it is sometimes the antennal, sometimes the maxillary gland which persists. The structure of both glands is essentially the same and they are to be regarded as the survivors of a primitive series of segmentally arranged nephridia. Each consists of a thin-walled "end-sac," which development shows to be a vestigial portion of the coelom, communicating with the exterior by a convoluted duct, part of which has glandular walls. Probably in most cases the greater part of this duct arises from mesoblast and only a short terminal part from epiblast, but it is stated that in some cases the whole duct is epiblastic. In the Decapoda the antennal gland is largely developed and is known as the "green gland." The external part of the duct is often dilated into a bladder, and may sometimes send out diverticula forming a system of sinuses ramifying through the body.

Other excretory organs have been described in certain Crustacea, consisting of groups of mesodermal cells in various parts of the body within which the excretory products are stored up instead of being expelled. Possibly some of these are vestiges of seg mentally arranged Nephridia.

Nervous System.

The central nervous system is constructed on the same general plan as in other Arthropoda, consisting of a supraoesophageal ganglionic mass or "brain," united by oesophageal connectives with a double ventral chain of tally arranged ganglia. In the primitive Branchiopoda the ventral chain retains the ladder-like arrangement found in some annelids, the two halves being widely separated and the pairs of ganglia connected together across the middle line by double transverse commissures. In the other groups the two halves of the chain are more or less coalesced, and, in addition, the ganglia tend to draw together in a longitudinal direction and to fuse, ultimately, into a single mass representing the whole of the ventral chain. This is seen, for example, in the true crabs (Brachyura) among the Decapoda. The brain, or supraoesophageal ganglion, shows various degrees of complexity. In the Branchiopoda it contains two pairs of ganglionic centres giving origin, respectively, to the optic and the antennular nerves. The centres for the antennal nerves form ganglionic swellings on the oesophageal connectives. In the higher forms these centres have moved forwards to become incorporated in the brain, but the fibres which unite them still run backwards to form a transverse commissure behind the oesophagus. This is of importance as showing that the antennae were originally postoral limbs: In the higher Decapoda, additional centres are developed in the brain and its structure becomes very complex. A system of visceral nerves and ganglia associated with the mentary canal and the heart is well developed in the Decapoda. Eyes.—The eyes of Crustacea are of two kinds, the unpaired, median or "nauplius" eye, and the paired compound eyes. The median eye is generally present in the earliest larval stages lius) and in some instances, as in the Copepoda, it forms the sole organ of vision. It may persist along with the paired eyes, as in the Branchiopoda, or it may become vestigial or disappear in the adult, as in most Malacostraca. It consists typically of three shaped masses of pigment, the cavity of each cup being filled with columnar retinal cells connected at their outer ends with nerve fibres from the brain.The compound eyes are very similar in the details of their structure to those of insects, consisting of a varying number of visual elements or "ommatidia" separated by pigment sheaths and each terminating in a "crystalline body" covered by the trans parent external cuticle which forms the cornea. In most cases the cornea is divided into lens-like facets cor responding to the underlying ommatidia.

Other Sense-organs.

As in other Ar thropoda, the hairs or setae on the surface of the body are important organs of sense and are variously modified for special func tions. Many, perhaps all, of them are or gans of the sense of touch. When feathered or provided with secondary barbs the setae will respond to movements or vibrations in the surrounding water and some of this sort have been supposed to have an audi tory function. Organs formerly regarded as auditory, but now known to be con nected with the maintenance of equilibrium of the body, are the "statocysts" found in various positions in different Crustacea, notably at the base of the antennules in most Decapods. These are open or closed vesicles having sensory hairs on their inner surface and containing one or more "stato liths" which may be grains of sand intro duced from the exterior.Another type of sensory setae is asso ciated with the sense of smell, or rather, perhaps, the "chemical sense." These are bluntly pointed filaments in which the cuticle is extremely delicate. They are found chiefly on the antennules, and are often especially developed in the males, which they are supposed to guide in their pursuit of the females.

Glands.

The most important glandular structures in Crus tacea (in addition to the digestive and excretory glands already mentioned) are various types of dermal glands which occur on the surface of the body and limbs. Some of these in the neigh bourhood of the mouth or on the walls of the oesophagus have been regarded as salivary, but in some cases are now known to produce a mucous secretion which serves to entangle minute food-particles and is swallowed along with them. In some Amphi poda the secretion of glands on the surface of the body and limbs is used in the construction of protective cases in which the animals live. In some freshwater Copepoda the dermal glands secrete a gelatinous envelope enabling the animals to resist desiccation. The greatly-developed cement glands of the Cirripedia which serve to attach the animals to their support probably also belong to the category of dermal glands.

Phosphorescent Organs.

Like many other marine animals certain Crustacea belonging to very diverse groups (Ostracoda, Copepoda, Mysidacea, Euphausiacea, Decapoda) possess the power of emitting light. All of them are inhabitants of the deep sea or of the surface waters of the ocean. No freshwater Crustacea are phosphorescent. The organs concerned in light-production are curiously varied. In the Ostracoda and Copepoda certain dermal glands produce a luminous secretion. In some Mysidacea and Decapoda the secretion of the excretory organs (maxillary or antennal glands) is luminous. In the Euphausiacea and certain Decapoda the light-producing organs found on the body and limbs are complex structures provided with a reflector and a condensing lens and movable by special muscles so as to vary the direction of the emitted beam. The part which phosphorescence plays in the life of the animals can only be conjectured. In some instances it may serve to attract prey; in others it may help individuals of the same species to keep to gether in a shoal or to find their mates. The clouds of luminous secretion thrown out by some species may serve to baffle pur suers like the cloud of ink thrown out by a cuttlefish. The elaborate "search-lights" may illuminate objects within the range of vision. But even conjecture seems at a loss when we find that certain deep-sea prawns have complex light-organs placed so as to il luminate the interior of the gill chambers.

Reproductive System..

In the great majority of Crustacea the sexes are separate, but in the Cirripedia and in some parasitic Isopoda hermaphroditism is the rule, and isolated instances occur in other groups, especially among Decapoda. Parthenogenesis is common in Branchiopoda and Ostracoda and occurs in at least one genus of terrestrial Isopoda. Where the sexes are separate, sexual dimorphism is often striking. The males are often provided with clasping organs for holding the female, and these may be formed by modification of almost any of the appendages, antennules, antennae, thoracic limbs, or even some of the mouth-parts. Some of the appendages in the neighbourhood of the genital openings may be modified for the purpose of transferring the sperm to the female, as, for instance, the first and second abdominal append ages in the Decapoda.In the higher Decapoda the male is often larger than the female, but in other groups the reverse is more frequently the case. In some parasitic Copepoda and Isopoda the disparity in size is car ried to an extreme degree, and the minute male is attached, like a parasite, to the enormously larger female.

In the Cirripedia some very aberrant types of sexual relation ship exist. While the great majority are hermaphrodites capable of both cross and self fertilization, it was discovered by Darwin that, in certain species, minute degraded males exist, attached to the ordinary individuals. Since these dwarf males pair, not with females, but with hermaphrodites, Darwin termed them "comple mental" males. In other species the large individuals have be come purely female by atrophy of the male organs and are entirely dependent on the dwarf males for fertilization.

Very few Crustacea are viviparous in the sense that the eggs are retained within the body until hatching takes place, but, on the other hand, nearly all carry the eggs in some way or other after extrusion. They are retained between the valves of the carapace in some Branchiopoda and Ostracoda or within the mantle-cavity in Cirripedia. Among the Malacostraca the Peracarida have a brood-pouch formed by overlapping plates attached to the bases of some of the thoracic legs. In the Decapoda the eggs are carried by the female attached to the abdominal appendages. In a few cases the developing embryos are nourished by a special secre tion while in the brood-chamber (Cladocera, terrestrial Isopoda).

The majority of Crustacea are hatched from the egg in a form differing more or less from that of the adult, and pass through a series of free-swimming larval stages. There are many instances, however, in which the metamorphosis is suppressed, and the newly-hatched young resemble th parent in general structure.

In those Crustacea in which the series of larval stages is most complete the starting-point is the form already mentioned under the name of nauplius. In the typical form, this has an oval un segmented body and three pairs of limbs corresponding to the antennules, antennae and mandibles of the adult. The antennules are simple, the others each two-branched, and all three pairs are used in swimming. The antennae have a spine-like process at the base, and they share with the mandibles, which have a similar process, the function of seizing food and pushing it into the mouth. The mouth is overhung by a large labrum or upper lip. The paired eyes are as yet wanting, but the unpaired eye is usually Lonspicuous.

A nauplius larva differing only in details from that just de scribed is found in most of the Branchiopoda, Copepoda and Cirri pedia, and in a more modified form, in some Ostracoda. Among the Malacostraca, the nauplius is found in the Euphausiacea and some of the most primitive Decapoda. In many of the Crustacea that hatch at a later stage there is more or less clear evidence of a nauplius stage in the embryonic development. It seems certain, therefore, that the possession of a nauplius larva must be regarded as a very primitive character of the Crustacea.

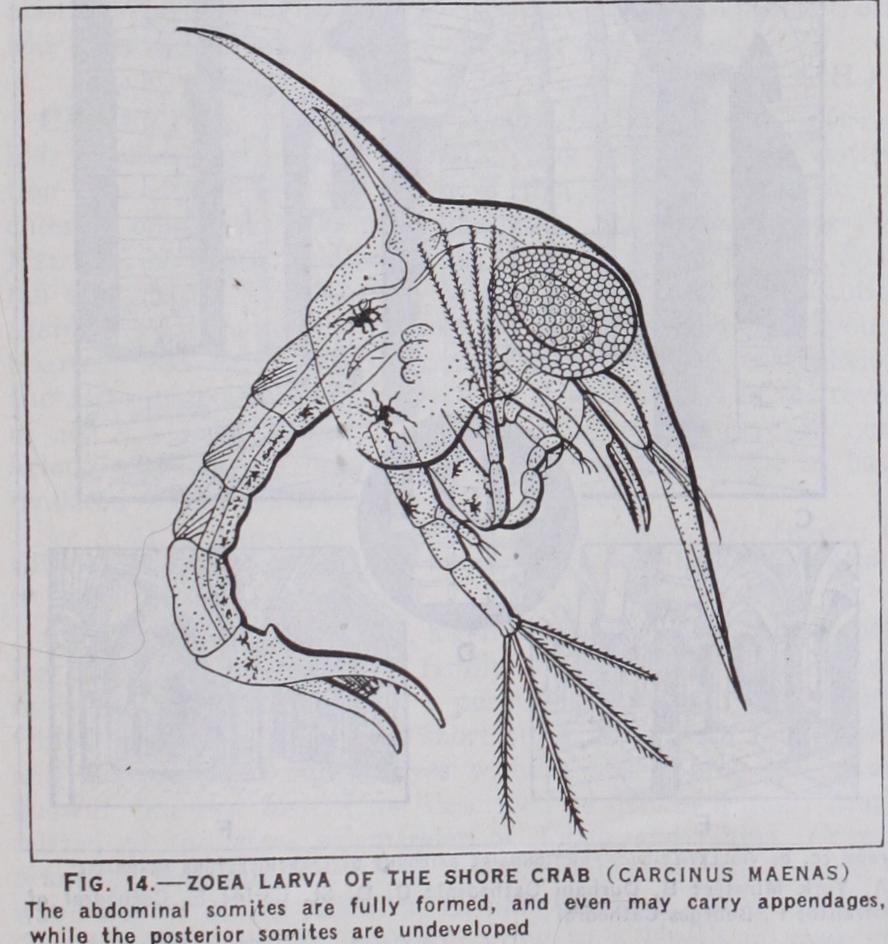

As development proceeds, the body of the nauplius elongates and its posterior part becomes segmented, new somites being added at successive moults from a formative zone in front of the telsonic region. The appendages appear as buds on the ventral surface of the somites, and become differentiated, like the somites that bear them, in regular order from before backwards. With the elongation of the body, its dorsal covering begins to project behind as a shell-fold, the beginning of the carapace. The paired eyes appear under the cuticle at the sides of the head, but only become pedunculated at a comparatively late stage.

The course of development here outlined, in which the somites and appendages appear in regular order, agrees so well with that observed in the typical Annelida that it must be regarded as the most primitive. It is most closely followed in some Branchiopoda and Copepoda. In most Crustacea, however, this primitive scheme is more or less modified. The earlier stages may be passed through within the egg, so that the larva, on hatching, has reached a stage Fossil remains of Crustacea are abundant in strata belonging to all the main divisions of the geological time-scale from the most ancient up to the most recent, but they teach us disappoint ingly little regaruing the phylogeny of the class. This is partly due to the fact that many important forms must have escaped fossilization altogether owing to their small size and delicate structure, while very many of those actually preserved are known only from the carapace or shell, the limbs being absent or repre sented only by indecipherable fragments. The fortunate accident which has preserved with marvellous completeness the minute branchiopod Lepidocaris in the rhynie chert (old red sandstone) is not likely to have been often repeated. But Lepidocaris is of recent date as compared with the varied fauna of Crustacea dis covered by Walcott in the Middle Cambrian of the Canadian Rockies and there is reason to believe that many of the chief groups were already differentiated before the beginning of the geological record as we now know it. Shrimp-like forms that can be definitely referred to the Malacostraca begin to appear in the Upper Devonian and Mysidacea and Syncarida can be recognized in the Carboniferous, but it is not until true decapods appear in the Trias that anything like a connected story can be made out.

In the dearth of trustworthy evidence from palaeontology we are compelled to rely on the data afforded by comparative anat omy and embryology in attempting to reconstruct the course of evolution within the class. It is perhaps unnecessary to insist that conclusions reached in this way must remain more or less speculative so long as they cannot be checked by the results of palaeontology.

The earlier attempts to reconstruct the genealogical history of the Crustacea started from the assumption that the successive stages of the larval history, especially the nauplius and zoea, reproduced the actual structure of ancestral types. It is now generally agreed that this "theory of recapitulation" cannot be applied to the zoea, the characters of which must be due to secondary modification. As regards the nauplius, however, the constancy of its general structure in the most diverse groups of Crustacea strongly suggests that it is a very ancient type, and the view has been strongly advocated that the Crustacea must have arisen from an unsegmented nauplius-like ancestor.

The objections to this view, however, are considerable. The resemblances between the more primitive Crustacea and the annelid worms, in such characters as the structure of the nervous system and the mode of growth of the somites, can hardly be ignored, and it is reasonable to suppose that the Crustacea origi nated from some stock which already possessed these characters.

If we are to attempt to reconstruct a hypothetical ancestral crustacean, we must suppose it to have in general form, to some such branchiopod as Apus, with an elongated body composed of numerous similar somites and ending in a caudal fork, with a carapace originating as a shell-fold from the maxil lary somite, with the eyes, probably, stalked, and the antennae and mandibles both biramous and armed with masticatory proc esses, and with the trunk-limbs all similar, biramous, with addi tional endites and exites, and probably all bearing gnathobases. It is to be noted that, except for the absence of a carapace-fold and of eye-stalks, the trilobites are not very far removed from the primitive crustacean here sketched.