Crypt

CRYPT, a vault or subterranean chamber, especially under a church floor. In Latin, crypta designated any vaulted building partially or entirely below the ground level, such as a sewer (crypta Szcburae, Juvenal, Sat. v., 1o6) ; the vaulted stalls for horses and chariots in a circus; farm storage cellars (Vitruvius vi., 8) ; and a long, vaulted gallery known as crypto porticus, like that on the Palatine hill. Seneca (Epist. 57) calls the tunnel now known as the Grotto of Posilipo, through which the road passes to Puteoli, crypta Neapolitana. It was natural, therefore, for the early Christians to call their catacombs crypts, and when churches came to be built over the tombs of saints and martyrs, subter ranean chapels, known as coca f essiones, around the actual tomb, were included. These also were called crypts. The most famous of these was St. Peter's, built on the site of St. Peter's martyrdom, over the circus of Nero (fourth century). Other notable Roman examples are those of S. Prisca, S. Prassede and S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura. In the basilica of S. Maria Maggiore a crypt was fur nished, although there was no tomb or martyrdom site to com memorate; it is interesting that as early as this Constantinian church, the crypt was considered a normal part of the church building.

Further incentive to the building of crypts was given by the growing practice of burials within the church walls. This was a much debated usage, and the Council of Braga (563) gave per mission for burials only within the churchyard, but not within the church itself. The Council of Mainz (813), however, stated that no one should be buried in a church except bishops, abbots, worthy priests or loyal laymen, and from that time burials within the church multiplied. These were usually in the crypt. An early example of such a burial crypt exists in the church of S. Apoll inare in Classe, Ravenna (sixth century), where it takes the form of a small, underground passage around the altar and just within the apse walls (see APSE) . Later the size of the crypt was in creased to include the entire space under the floor of the church choir (q.v.), as in the tenth century crypt of S. Ambrogio at Milan. With the increased desire for richness in all parts of the church and increased technical skill, a further step was taken by raising the choir floor boldly and opening the front of the crypt to the nave (q.v.), which was on an intermediate level between the crypt and the choir, with monumental flights of steps leading down to the crypt in the centre and up to the choir on either side. The arcaded fronts of these crypts form an effective decoration for the church, as in the 12th century church of S. Zeno in Verona, and that of S. Miniato at Florence (1013). The latter is particu larly rich with inlaid polychrome marbles. These crypts within were usually apsidal and the ranges of columns whose vaults supported the floor above gave interesting perspective effects. Where Byzantine influence was strong, crypts are less common, and when found, are of a totally different type, frequently exist ing as cellars under the entire church area, as in Trani cathedral in southern Italy (12th century), apparently designed by an archi tect named Nicolaus Sacerdos. St. Mark's at Venice has a remark able crypt of Greek cross plan, with many short and stumpy col umns. This crypt is, in fact, a secondary church ; its choir screen is still extant.

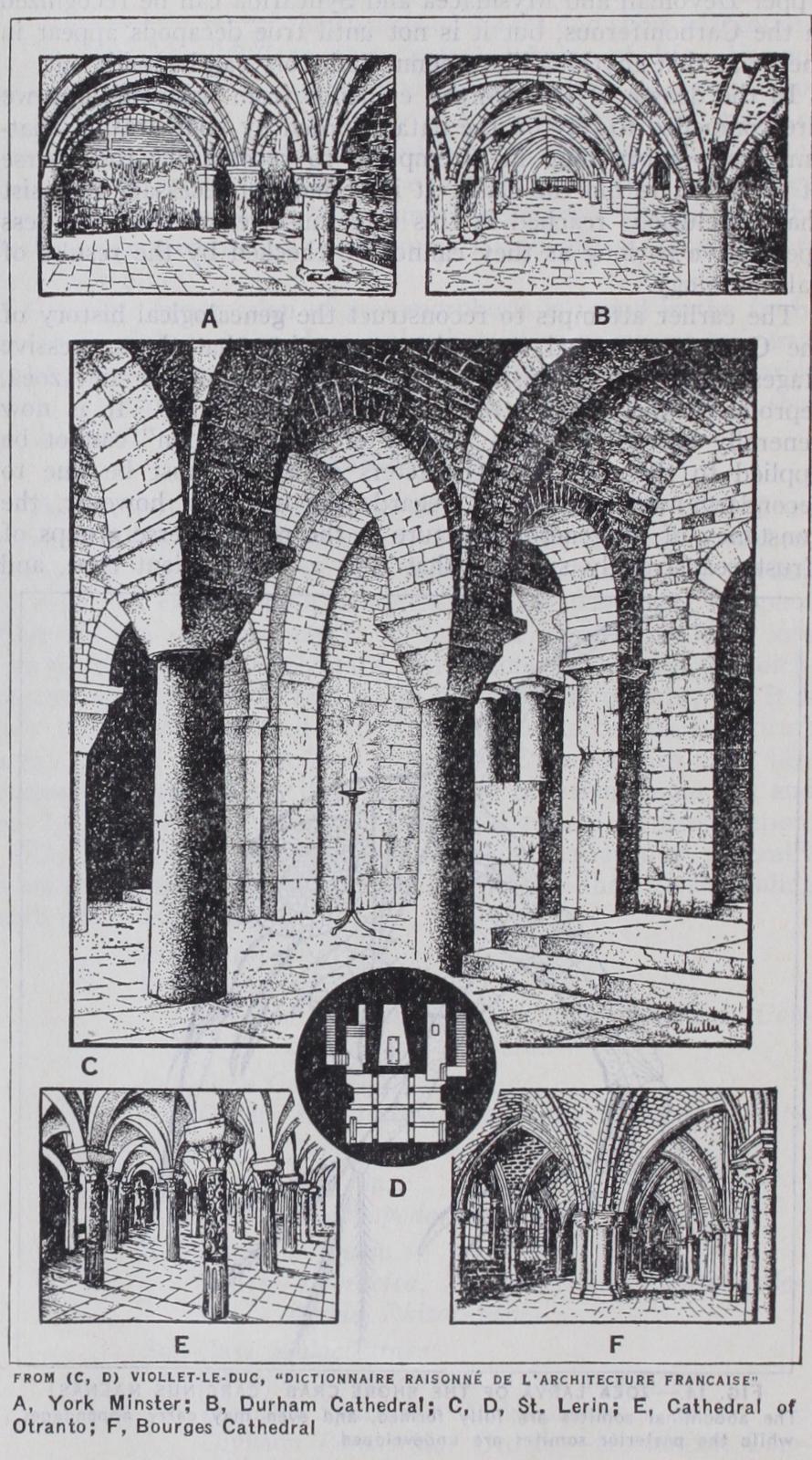

Outside Italy there is great variation both in frequency and size of crypts. Lombard influence in Germany is shown by the number of Rhenish churches that follow the Italian precedent of an appreciably raised choir with an important crypt beneath it. The end beneath the nave is usually closed, however. Elsewhere in western Europe the choir level is much less raised and the crypt, where present, tends more and more to become a lower church with a plan largely reproducing that of the church above. The cathedral of S. Benigne at Dijon possesses the strange crypt of a curious round chapel which seems to date back to the sixth cen tury. It was built over the tomb of the patron saint and is pe culiar in the fact that the central circular area, surrounded by a double aisle, ran up through the upper portion of the building and was open to the sky. There is also a remarkable crypt in the cathedral of Auxerre believed to date from 1o85, and several ex amples in Normandy, notably that of Bayeux and the Abbaye aux Dames at Caen, both of the late i 1 th century. These are in a crude Norman style with many similarities to contemporary crypts in England. The crypts of Chartres and Bourges cathedrals deserve notice as instances of the more developed type of early Gothic of the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

Crypts were highly developed in English work throughout the Romanesque and Gothic periods (see BYZANTINE AND ROMAN ESQUE ARCHITECTURE; GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE). The one at Canterbury, the western half of which is attributed to Ernulf (c. I Too), and the eastern half to William the Englishman, 75 years later, forms a large and complex church, with apse and chapels. The extreme east end, under Trinity chapel, is famous as the original burial-place of Thomas a Becket. Slightly earlier (late 1 ith century), the crypts of Winchester, Worcester and Gloucester are similarly apsidal, but simpler in plan. Of these Worcester (Io84), is the most decorative. Parts of the crypt at Rochester, that at Hereford and the crypt, no longer existing, of old St. Paul's in London, were of rich Gothic type, the last so large that it served as the parish church of St. Faith. Other no table examples in Great Britain are the exquisite crypt of St. Stephen's chapel at Westminster, now incorporated within the Houses of Parliament, and the richly carved 13th century crypt of the cathedral at Glasgow. Small crypts under parish churches are common in England, as at Lastingham in Yorkshire (probably io8o), notable for its size and the crude pseudo-classic character of its ornament ; and at Repton in Derbyshire ; another very fine Norman example is the crypt of St. Peter's-in-the-East at Oxford.

Technically, as many mediaeval houses were built over vaulted substructures, they may be said to have had crypts, and remains of such non-ecclesiastical crypts occur widely throughout Europe. The German Rathaiiser have many fine and richly decorated crypts, such as the famous cellar of the Bremen town-hall ; a notable mon astic cellar still exists in Mainz, and the cellars of the residential buildings at Mont St. Michel in France furnish numerous examples of great size and magnificence, in almost all the mediaeval styles dating from the iith to the ith century. Oxford, Rochester and Bristol, in England, contain many remains of vaulted mediaeval cellars, and the city of Chester is built, in great areas, over ranges of such vaults. Notable examples in London are those of Gerard's Hall, now destroyed (reign of Edward I.), and that of the Guildhall, which dates from 141 1, and is notable for its rich and intricate ribbed vault, in the design of which the subsidiary ribs, called liernes, play an important part.

Many great modern cathedrals contain crypts. Notable examples exist at Washington, D.C. and St. John the Divine, New York, which contains an elaborate mosaic altar and reredos.

(T. F. H.)