Crystalline Form

CRYSTALLINE FORM The fundamental laws governing the form of crystals are:— I. Law of the Constancy of Angle.

2. Law of Symmetry.

3. Law of Rational Intercepts or Indices.

According to the first law, the angles between corresponding faces of all crystals of the same chemical substance are always the same and are characteristic of the substance.

Crystals may, or may not, be symmetrical with respect to a point, a line or axis, and a plane; these "elements of symmetry" are spoken of as a centre of symmetry, an axis of symmetry, and a plane of symmetry respectively.

Centre of Symmetry.—Crystals which are centro-symmetrical have their faces arranged in parallel pairs ; and the two parallel faces, situated on opposite sides of the centre (0 in fig. 3) are alike in surface characters, such as lustre, striations and figures of corrosion. An octahedron (fig. 3) is bounded by four pairs of parallel faces. Crystals belonging to many of the hemihedral and tetartohedral classes of the six systems of crystallization are devoid of a centre of symmetry.

Axes of Symmetry.—Consider the vertical axis joining the opposite corners and of an octahedron (fig. 3) and passing through itscentre by rotating the crystal about this axis through a right angle (90°) it reaches a position such that the orientation of its faces is the same as before the rotation ; the face for example, coming into the position of During a complete rotation of 360° (= 90° X4), the crystal occu pies four such interchangeable positions. Such an axis of sym metry is known as a tetrad axis of sym metry. Other tetrad axes of the octa hedron are and An axis of symmetry of another kind is that which passing through the centre 0 is normal to a face of the octahedron. By rotating the crystal about such an axis Op (fig. 3) through an angle of t those faces which are not perpendicular to the axis occupy interchangeable positions; for example, the face comes into the position of and to During a complete rotation of 36o° (= r 2o° X 3) the crystal occupies similar positions three times. This is a triad axis of symmetry; and there being four pairs of parallel faces on an octahedron, there are four triad axes (only one of which is drawn in the figure).

An axis passing through the centre 0 and the middle points d of two opposite edges of the octahedron (fig. 4), i.e., parallel to the edges of the octahedron, is a dyad axis of symmetry. About this axis there may be rotation of 18o°, and only twice in a com plete revolution of 36o ° (= r 80° X 2) is the crystal brought into interchangeable positions. There being six pairs of parallel edges on an octahedron, there are consequently six dyad axes of symmetry.

A regular octahedron thus possesses thirteen axes of symmetry (of three kinds), and there are the same number in the cube. Fig. 5 shows the three tetrad (or tetragonal) axes (aa), four triad (or trigonal) axes (pp), and six dyad (diad Dr diagonal) axes (dd).

Although not represented in the cubic system, there is still another kind of axis of symmetry possible in crystals. This is the hexad axis or hexagonal axis, for which the angle of rotation is 60°, or one-sixth of 360°. There can be only one hexad axis of symmetry in any crystal. (See figs. 7 7-80. ) Planes of Symmetry.—A regular octahedron can be divided into two equal and similar halves by a plane passing through the corners and the centre 0 (fig. 3). One-half is the mirror reflection of the other in this plane, which is called a plane of sym metry. Corresponding planes on either side of a plane of symmetry are inclined to it at equal angles. The hedron can also be divided by similar planes of symmetry passing through the corners and These three similar planes of symmetry are called the cubic planes of symmetry, since they are parallel to the faces of the cube. (Compare figs. 6-8, showing combinations of the octahedron and the cube.) A regular octahedron can also be divided symmetrically into two equal and similar portions by a plane passing through the corners and the middle points d of the edges and and the centre 0 (fig. 4). This is called a dodecahedral plane of symmetry, being parallel to the face of the rhombic dodecahedron which truncates the edge a,az. (Compare fig. 14, showing a bination of the octahedron and rhombic dodecahedron.) Another similar plane of symmetry is that passing through the corners and the middle points of the edges and and altogether there are six dodecahedral planes of symmetry, two through each of the corners of the octahedron.

A regular octahedron and a cube are thus each symmetrical with respect to the following elements of symmetry: a centre of symmetry, thirteen axes of symmetry (of three kinds), and nine planes of symmetry (of two kinds). This degree of symmetry, which is the type corresponding to one of the classes of the cubic system, is the highest possible in crystals. As will be pointed out below, it is possible, however, for both the octahedron and the cube to be associated with fewer elements of symmetry than those just enumerated.

(b) Sirz ple Forms and Combinations of Forms A single face alaza3 (figs. 3 and 4) may be repeated by certain of the elements of symmetry to give the whole eight faces of the octahedron. Thus, by rotation about the vertical tetrad axis the four upper faces are obtained; and by rotation of these about one or other of the horizontal tetrad axes the eight faces are de rived. Or again, the same repeti tion of the faces may be arrived at by reflection across the three cubic planes of symmetry. (By reflection across the six dodeca hedral planes of symmetry a tetrahedron only would result, but if this is associated with a centre of symmetry we obtain the octahedron.) Such a set of similar faces, obtained by symmetrical repetition, constitutes a "simple form." An octahedron thus con sists of eight similar faces, and a cube is bounded by six faces all of which have the same surface characters and parallel to each of which all the properties of the crystal are identical.

Examples of simple forms amongst crystallized substances are octahedra of alum and spinel and cubes of salt and fluorspar. More usually, however, two or more forms are present on a crystal, and we then have a combination of forms, or simply a "combination." Figs. 6, 7 and 8 represent combinations of the octahedron and the cube ; in the first the faces of the cube predominate, and in the third those of the octahedron; fig. 7 with the two forms equally developed is called a cubo-octahedron.

Each of these combined forms has all the elements of symmetry proper to the simple forms.

The simple forms, though referable to the same type of symmetry and axes of reference, are quite independent, and can not be derived one from the other by sym metrical repetition, but, after the manner of Rome de l'Isle, they may be derived by replacing edges or corners by a face equally inclined to the faces forming the edges or corners; this is known as "truncation." Thus in fig. 6 the corners of the cube are symmetrically replaced or truncated by the faces of the octahedron, and in fig. 8 those of the octahedron are truncated by the cube.

(c) Law of Rational Intercepts For axes of reference, OX, OY, OZ (fig. 9), take any three edges formed by the intersection of three faces of a crystal. These axes are called the crystallographic axes, and the planes in which they lie the axial planes. A fourth face on the crystal inter secting these three axes in the points A, B, C is taken as the parametral plane, and the lengths OA :0 B :0C are the para meters of the crystal. Any other face on the crystal may be re ferred to these axes and parameters by the ratio of the intercepts Thus for a face parallel to the plane ABe the intercepts are in the ratio OA :0B :0e, or Now the important relation existing between the faces of a crystal is that the denominators h, k and l are always rational whole numbers, rarely exceeding 6, and usually o, I, 2 or 3. Written in the form { hkl } , h referring to the axis OX, k to OY, and 1 to OZ, they are spoken of as the indices (Millerian indices) of the face. Thus of a face parallel to the plane ABC the indices are {III} , of ABe they are {112} and of fgC 1231). The in dices are thus inversely proportional to the intercepts, and the law of rational in tercepts is often spoken of as the "law of rational indices." The angular position of a face is thus completely fixed by its indices ; and know ing the angles between the axial planes and the parametral plane all the angles of a crystal can be calculated when the indices of the faces are known.

Although any set of edges formed by the intersection of three planes may be chosen for the crystallographic axes, it is in prac tice usual to select certain edges related to the symmetry of the crystal, and usually coincident with axes of symmetry; for then the indices will be simpler and all faces of the same simple form will have a similar set of indices. The angles between the axes and the ratio of the lengths of the parameters OA :OB :OC (usually given as a : b : c) are spoken of as the "elements" of a crystal, and are constant for and characteristic of all crystals of the same substance.

The six systems of crystal forms, to be enumerated below, are defined by the relative inclinations of the crystallographic axes and the lengths of the parameters. In the cubic system, for ex ample, the three crystallographic axes are taken parallel to the three tetrad axes of symmetry, i.e., parallel to the edges of the cube (fig. 5) or joining the opposite corners of the octahedron (fig. 3), and they are therefore all at right angles; the parametral plane (III) is a face of the octahedron, and the parameters are all of equal length. The indices of the eight faces of the hedron will then be {III}, { iii}, { {III}, {III {III}, The symbol {III} indicates all the faces belonging to this simple form. The indices of the six faces of the cube are oio }, { ooi}, { ioo}, { oio}, { col) ; here each face is par allel to two axes, i.e., intercepts them at infinity, so that the corre sponding indices are zero.

(d) Zones An important consequence of the law of rational intercepts is the arrangement of the faces of a crystal in zones. All faces, whether they belong to one or more simple forms, which intersect in parallel edges are said to lie in the same zone. A line drawn through the centre 0 of the crystal parallel to these edges is called a zone-axis, and a plane perpendicular to this axis is called a zone-plane. On a cube, for example, there are three zones each containing four faces, the zone-axes being coincident with the three tetrad axes of symmetry. In the crystal of zircon (fig. 88) the eight prism-faces, a, m, etc., constitute a zone, denoted by [a, m, a', etc.], with the ver tical tetrad axis of symmetry as zone axis. Again the faces [a, x, p, lie in another zone, as may be seen by the parallel edges of intersection of the faces in figs. 87 and 88; three other similar zones may be traced on the same crystal.

The direction of the line of intersection (i.e., zone-axis) of any two planes { hkl } and { } is given by the zone-indices [uvw], where and w = these being obtained from the face-indices by cross multiplication as follows: h k l h k l X X X Any other face lying in this zone must satisfy the equation = o.

This important relation connecting the indices of a face lying in a zone with the zone-indices is known as Weiss's zone-law, hav ing been first enunciated by C. S. Weiss.

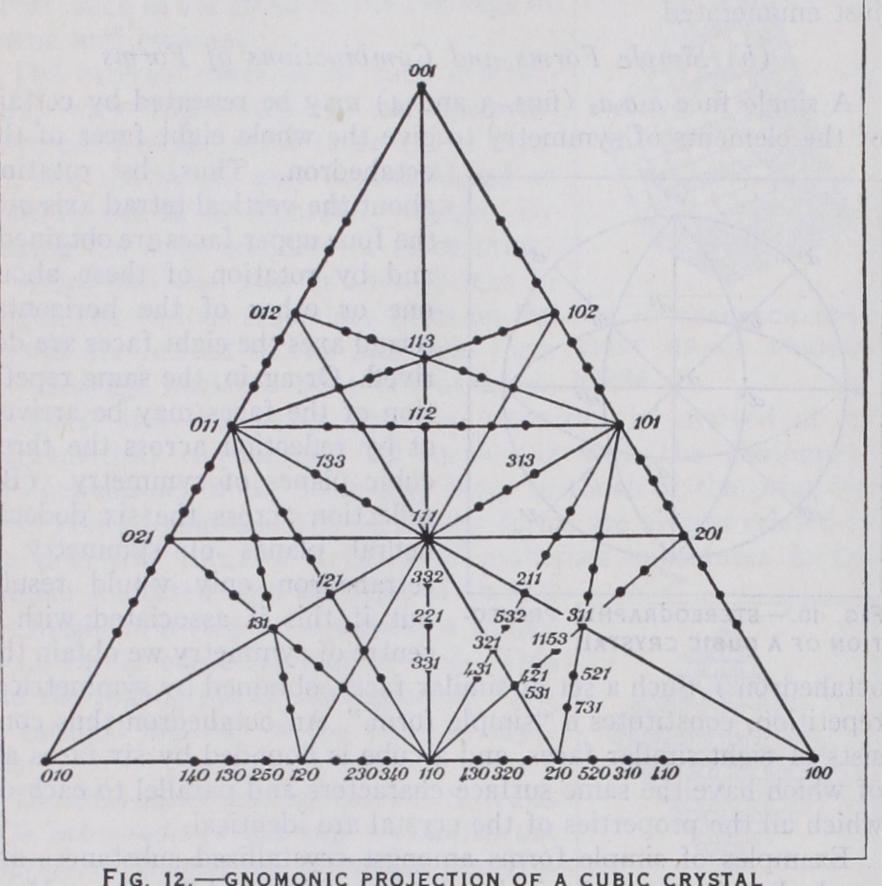

It may be pointed out that the indices of a face may be arrived at by adding together the indices of faces on either side of it and in the same zone; thus 13111 in fig. 12 lies at the intersections of the three zones { 210, Ioi}, {2o1, iio}jand {211, zoo} and is obtained by adding together each set of indices.

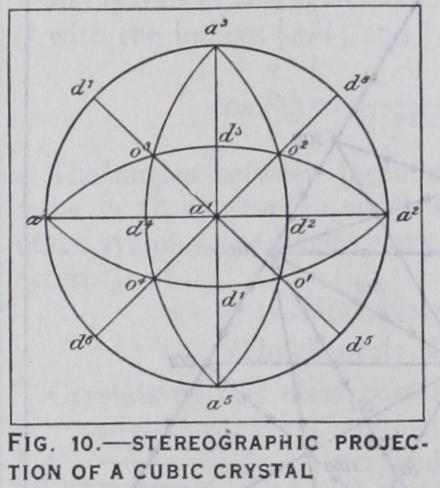

(e) Projection and Drawing of Crystals The shapes and relative sizes of the faces of a crystal being as a rule accidental, depending only on the distance of the faces from the centre of the crystal and not on their angular relations, it is often more con venient to consider only the directions of the normals to the faces. For this pur pose projections are drawn, with the aid of which the zonal relations of a crystal are more readily studied and calculations are simplified. The kind of projection most extensively used is the "stereo graphic projection." The crystal is considered to be placed inside a sf.here from the centre of which normals are drawn to all the faces of the crystal. The points at which these normals inter sect the surface of the sphere are called the poles of the faces, and by these poles the positions of the faces are fixed. The poles of all faces in the same zone on the crystal will lie on a great circle of the sphere, which are therefore called zone-circles. The calcu lation of the angles between the normals of faces and between zone-circles is then performed by the ordinary methods of spheri cal trigonometry. The stereographic projection, however, repre sents the poles and zone-circles on a plane surface and not on a spherical surface. This is achieved by drawing lines joining all the poles of the faces with the north or south pole of the sphere and finding their points of intersection with the plane of the equatorial great circle, or primitive circle, of the sphere, the pro jection being represented on this plane. In fig. io is shown the stereographic projection, or stereogram, of a cubic crystal; a', etc., are the poles of the faces of the cube, ol, etc., those of the octahedron, and di, etc., those of the rhombic dodecahedron. The straight lines and circular arcs are the projections on the equatorial plane of the great circles in which the nine planes of symmetry inter sect the sphere. A drawing of a crystal showing a combination of the cube, octa hedron and rhombic dodecahedron is shown in fig. I I, in which the faces are lettered the same as the corresponding poles in the pro jection. From the zone-circles in the pro jection and the parallel edges in the draw ing the zonal relations of the faces are readily seen: thus [alold'] , etc., are zones. A stereographic projection of a rhombohedral crystal is given in fig. 72.

Another kind of projection in common use is the "gnomonic projection" (fig. 12).

Here the plane of projection is tangent to the sphere, and normals to all the faces are drawn from the centre of the sphere to intersect the plane of projection. In this case all zones are represented by straight lines. Fig. 12 is the gnomonic projection of a cubic crystal, the plane of projection being tangent to the sphere at the pole of an octahedral face {III } , which is therefore in the centre of the projection. The indices of the several poles are given in the figure.

In drawing crystals the simple plans and elevations of descrip tive geometry (e.g., the plans in the lower part of figs. 87 and 88) have sometimes the advantage of showing the symmetry of a crystal, but they give no idea of solidity. For instance, a cube would be represented merely by a square, and an octahedron by a square with lines joining the opposite corners. True perspective drawings are never used in the representa tion of crystals, since for showing the zonal relations it is important to preserve the parallelism of the edges. If, however, the eye, or point of vision, is regarded as being at an infinite distance from the object all the rays will be parallel, and edges which are parallel on the crystal will be repre sented by parallel lines in the drawing. The plane of the drawing, in which the parallel rays joining the corners of the crystals and the eye intersect, may be either perpendic ular or oblique to the rays; in the former case we have an orthographic drawing, and in the latter a clinographic drawing. Clinographic drawings are most frequently used for representing crystals. In representing, for example, a cubic crystal (fig. I I) a cube face is first placed parallel to the plane on which the crystal is to be projected and with one set of edges vertical; the crystal is then turned through a small angle about a vertical axis until a second cube face comes into view, and the eye is then raised so that a third cube face a' may be seen.

(f) Crystal Systems and Classes According to the mutual inclinations of the crystallographic axes of reference and the lengths intercepted on them by the para metral plane, all crystals fall into one or other of six groups or systems, in each of which there are several classes depending on the degree of symmetry. In the brief description which follows of these six systems and thirty-two classes of crystals we shall pro ceed from those in which the Symmetry is most complex to those in which it is simplest.

1. CUBIC SYSTEM (Isometric ; Regular ; Octahedral; Tesseral.) In this system the three crystallographic axes of reference are all at right angles to each other and are equal in length. They are parallel to the edges of the cube, and in the different classes co incide either with tetrad or dyad axes of symmetry. Five classes are included in this system, in all of which there are, besides other elements of symmetry, four triad axes.

In crystals of this system the angle between any two faces P and Q with the indices { hkl } and { pqr } is given by the equation The angles between faces with the same indices are thus the same in all substances which crystallize in the cubic system : in other systems the angles vary with the substance and are char acteristic of it.

H0L0SYMMETRIC CLASS (Holohedral ; Hexakis-octahedral.) Crystals of this class possess the full number of elements of symmetry already mentioned above for the octahedron and the cube, viz., three cubic planes of symmetry, six dodecahedral planes, three tetrad axes of symmetry, four triad axes, six dyad axes and a centre of symmetry.

There are seven kinds of simple forms, viz.: Cube (fig. 5) .—This is bounded by six square faces parallel to the cubic planes of symmetry ; is known also as the hexahedron.

The angles between the faces are go°, and the indices of the form are { Ioo} . Salt, fluorspar and galena crystallize in simple cubes.

Octahedron (fig. 3).—Bounded by eight equilateral triangular faces perpendicular to the triad axes of symmetry. The angles between the faces are 7o° 32' and 109° 28', and the indices are { 'III. Spinel, magne tite and gold crystallize in simple octa hedra. Combinations of the cube and octa hedron are shown in figs. 6-8.

Rhombic dodecahedron (fig. 13) . Bounded by twelve rhomb-shaped faces parallel to the six dodecahedral planes of symmetry. The angles between the nor mals to adjacent faces are 6o°, and between other pairs of faces go° ; the indices are { I I o } . Garnet frequently crystallizes in this form. Fig. 14 shows the rhombic dodeca hedron in combination with the octahedron.

In these three simple forms of the cubic system (which are shown in combination in fig. I I) the angles between the faces and the indices are fixed and are the same in all crystals ; in the four remaining simple forms they are variable.

Triakis-octahedron (three-faced octahedron) (fig. 15).—This solid is bounded by twenty-four isosceles triangles, and may be considered as an octahedron with a low triangular pyramid on each of its faces. As the inclinations of the faces may vary there is a series of these forms with the indices { 2 21 }, { 331 }, { 3321, etc., or in general { hhk } .

Icositetrahedron (fig. 17).—Bounded by twenty-four trape zoidal faces, and hence sometimes called a "trapezohedron." The indices are { 211 }, { 31 I }, {3221, etc., or in general { hkk }. Anal cime, leucite and garnet often crystallize in the simple form { 2 I 1 } . Combinations are shown in figs. 18-20. The plane ABe in fig. 9 is one face { I I 2 } of an icositetrahedron ; the indices of the remain ing faces in this octant being { 211} and { I2I } .

Tetrakis-hexahedron (four-faced cube) (figs. 21 and 22).— Like the triakis-octahedron this solid is also bounded by twenty four isosceles triangles, but here grouped in fours over the cubic faces. The two figures show how, with different inclinations of the faces, the form may vary, approximat ing in fig. 21 to the cube and in fig. 22 to the rhombic dodecahedron. The angles over the edges lettered A are different from the angles over the edges lettered C. Each face is parallel to one of the crystallographic axes and intercepts the two others in dif ferent lengths ; the indices are therefore { 21O },{ 3 io },{ 32o), etc., in general { hko }.

Fluorspar sometimes crystallizes in the simple form { 3 I o } ; more usually, however, in combination with the cube (fig. 23) .

Hexakis-octahedron (fig. 24).—Here each face of the octahedron is replaced by six scalene triangles, so that altogether there are forty-eight faces. This is the greatest number of faces possible for any simple form in crystals. The faces are all oblique to the planes and axes of symmetry, and they intercept the three crystallographic axes in different lengths, hence the indices are all unequal, being in general { hkl } , or in particular cases { 3 2 I }, { 42 I 1, { 43 2 } , etc. Such a form is known as the "general form" of the class. The interfacial angles over the three edges of each triangle are all different. These forms usually exist only in combination with other cubic forms (for example, fig. 25), but { 4211 has been observed as a simple form on fluorspar.

Several examples of substances which crystallize in this class have been mentioned above under the different forms; many others might be cited—for instance, the metals iron, copper, silver, gold, platinum, lead, mercury and the non-metallic elements sili con and phosphorus.