Crystallography

CRYSTALLOGRAPHY, the science of the forms, proper ties and structure of crystals. Homogeneous solid matter, the physical and chemical properties of which are the same about every point, may be either amorphous or crystalline. In amor phous matter all the properties are the same in every direction in the mass; but in crystalline matter certain of the physical properties vary with the direction. The essential properties of crystalline matter are of two kinds, viz., the general properties, such as density, specific heat, melting-point and chemical corn position, which do not vary with the direction; and the direc tional properties, such as cohesion and elasticity, various optical, thermal and electrical properties, as well as external form. By rea son of the homogeneity of crystalline matter the directional properties are the same in all parallel directions in the mass, and there may be a certain symmetrical repetition of the directions along which the properties are the same.

When the crystallization of matter takes place under conditions free from outside influences the peculiarities of internal struc ture are expressed in the external form of the mass, and there re sults a solid body bounded by plane surfaces intersecting in straight edges, the directions of which bear an intimate relation to the internal structure. Such a polyhedron (crows, many, EBpa, base or face) is known as a crystal. An example of this is sugar candy, of which a single isolated crystal may have grown freely in a solution of sugar. Matter presenting well-defined and regular crystal forms, either as a single crystal or as a group of individual crystals, is said to be crystallized. If, on the other hand, crystal lization has taken place about several centres in a confined space, the development of plane surfaces may be prevented, and a crys talline aggregate of differently orientated crystal-individuals re sults. Examples of this are afforded by loaf sugar and statuary marble.

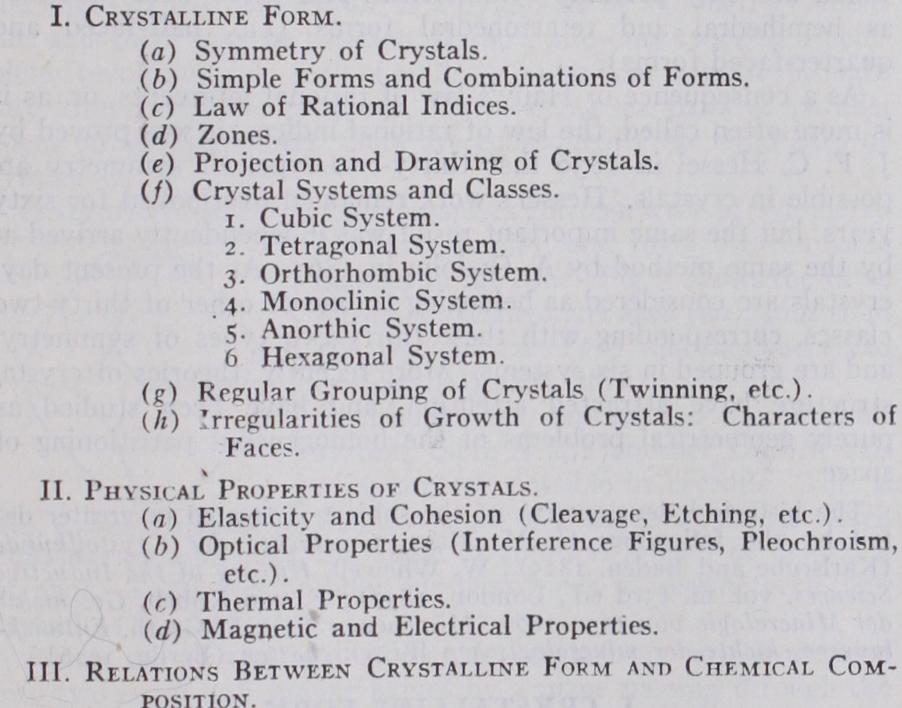

After a brief historical sketch, the more salient principles of the subject will be discussed under the following sections:— Most chemical elements and compounds are capable of assum ing the crystalline condition. Crystallization may take place when solid matter separates from solution (e.g., sugar, salt, alum), from a fused mass (e.g., sulphur, bismuth, felspar), or from a vapour (e.g., iodine, camphor, haematite; in the last case by the inter action of ferric chloride and steam). Crystalline growth may also take place in solid amorphous matter, for example, in the devitrifi cation of glass, and the slow change in metals when subjected to alternating stresses. Beautiful crystals of many substances may be obtained in the laboratory by one or other of these methods, but the most perfectly developed and largest crystals are those of mineral substances found in nature, where crystalliza tion has continued during long periods of time. For this reason the physical science of crystallography has developed side by side with that of mineralogy. Really, however, there is just the same connection between crystallography and chemistry as between crystallography and mineralogy, but only in recent years has the importance of determining the crystallographic properties of arti ficially prepared compounds been recognized.

History.—The word "crystal" is from the Gr. KpCoraXXos, meaning clear ice (Lat. crystallum), a name which was also ap plied to the clear transparent quartz ("rock-crystal") from the Alps, under the belief that it had been formed from water by intense cold. It was not until about the i 7th century that the word was extended to other bodies, either those found in nature or obtained by the evaporation of a saline solution, which resembled rock-crystal in being bounded by plane surfaces, and often also in their clearness and transparency.

The first important step in the study of crystals was made by Nicolaus Steno, the famous Danish physician, afterwards bishop of Titiopolis, who in his treatise De solido intro solidum naturaliter contento (Florence, 1669; English translation, 1671) gave the results of his observations on crystals of quartz. He found that although the faces of different crystals vary considerably in shape and relative size, yet the angles between similar pairs of faces are always the same. He further pointed out that the crys tals must have grown in a liquid by the addition of layers of mate rial upon the faces of a nucleus, this nucleus having the form of a regular six-sided prism terminated at each end by a six-sided pyramid. The thickness of the layers, though the same over each face, was not necessarily the same on different faces, but depended on the position of the faces with respect to the surrounding liquid; hence the faces of the crystal, though variable in shape and size, remained parallel to those of the nucleus, and the angles between them constant. Robert Hooke in his Micrograpliia (London, i 665 ) had previously noticed the regularity of the minute quartz crystals found lining the cavities of flints, and had suggested that they were built up of spheroids. About the same time the double re fraction and perfect rhomboidal cleavage of crystals of calcite or Iceland-spar were studied by Erasmus Bartholinus (Experi menta crystalli Islandici disdiaclastici, Copenhagen, 1669) and Christiaan Huygens (Traite de la lumiere, Leyden, 1690) ; the lat ter supposed, as did Hooke, that the crystals were built up of spheroids. In 1695 Anton van Leeuwenhoek observed under the microscope that different forms of crystals grow from the solu tions of different salts. Andreas Libavius had indeed much earlier, in 1597, pointed out that the salts present in mineral waters could be ascertained by an examination of the shapes of the crystals left on evaporation of the water; and Domenico Guglielmini (Riflessioni filosofiche dedotte dalle figure de dei Bali, Padova, asserted that the crystals of each salt had a shape of their own with the plane angles of the faces always the same.

The earliest treatise on crystallography is the Prodromus Crys tallographiae of M. A. Ca.ppeller, published at Lucerne in 1723. Crystals were mentioned in works on mineralogy and chemistry; for instance, C. Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae (1735) de scribed some forty common forms of crystals amongst minerals. It was not, however, until the end of the 18th century that any real advances were made, and the French crystallographers Rome de Lisle and the abbe Haiiy are rightly considered as the founders of the science. J. B. L. Rome de Lisle (Essai de cristallo graphie, Paris, 1772 ; Cristallographie, ou description des formes propres a tons les corps du regne mineral, Paris, 1783) made the important discovery that the various shapes of crystals of the same natural or artificial substance are all intimately related to each other; and further, by measuring the angles between the faces of crystals with the goniometer (q.v.), he established the funda mental principle that these angles are always the same for the same kind of substance and are characteristic of it. Replacing by single planes or groups of planes all the similar edges or solid angles of a figure called the "primitive form" he derived other related forms. Six kinds of primitive forms were distinguished, namely, the cube, the regular octahedron, the regular tetrahedron, a rhombohedron, an octahedron with a rhombic base, and a double six-sided pyramid. Only in the last three can there be any variation in the angles : for example, the primitive octahedron of alum, nitre and sugar were determined by Rome de Lisle to have angles of i io°, 120° and too° respectively. Rene Just Hauy in his Essai d'une theorie sur la structure des crystaux (Paris, 1784; see also his Treatises on Mineralogy and Crystallography, i8o1, 18 2 2) supported and extended these views, but took for his primi tive forms the figures obtained by splitting crystals in their direc tions of easy fracture of "cleavage," which are always the same in the same kind of substance. Thus he found that all crystals of calcite, whatever their external form (see, for example, figs. 1-6 in the article CALCITE), could be reduced by cleavage to a rhom bohedron with interfacial angles of 75°. Further, by stacking to gether a number of small rhombohedra of uniform size he was able, as had been previously done by J. G. Gahn in 1773, to recon struct the various forms of calcite crystals.

Fig. i shows a scalenohedron built up in this manner of rhombohedra ; and fig. 2 a regular octahedron built up of cubic ele ments, such as are given by the cleavage of galena and rock-salt.

The external surfaces of such a struc ture, with their step-like arrangement, correspond to the plane faces of the crys tal, and the bricks may be considered so small as not to be separately visible. By making the steps one, two or three bricks in width and one, two or three bricks in height, the various secondary faces on the crystal are related to the primitive form or "cleavage nucleus" by a law of whole numbers, and the angles between them can be arrived at by mathematical calculation. By measuring with the goniometer the inclinations of the secondary faces to those of the primitive form Hauy found that the secondary forms are always related to the primitive form on crystals of numerous substances in the manner indicated, and that the width and the height of a step are always in a simple ratio, rarely exceeding that of i :6. This laid the foundation of the important "law of rational indices" of the faces of crys tals.

The German crystallographer C. S. Weiss (De indagando formarum, crystallinarum charactere geometrico principali disserta tio, Leipzig, 1809 ; tf bersichtliche Darstel lung der verschiedenen naturlichen Abtheil ungen der Krystallisations-Systeme, Denk schrift der Berliner Akad. der Wissensch., 1814-1815) attacked the problem of crystalline form from a purely geometrical point of view, without reference to primitive forms or any theory of structure. The faces of crystals were considered by their inter cepts on co-ordinate axes, which were drawn joining the opposite corners of certain forms; and in this way the various primitive forms of Hauy were grouped into four classes, corresponding to the four systems described below under the names cubic, tetragonal, hexagonal and orthorhombic. The same result was arrived at independently by F. Mohs, who further, in 1822, asserted the existence of two addi tional systems with oblique axes. These two systems (the monoclinic and anorthic) were, however, considered by Weiss to be only hemihedral or tetartohedral modifica tions of the orthorhombic system, and they were not definitely established until when the optical characters of the crystals were found to be distinct. A system of no tation to express the relation of each face of a crystal to the co-ordinate axes of reference was devised by Weiss, and other notations were proposed by F. Mohs, A. Levy (1825), C. F. Naumann (1826), and W. H. Miller (Treatise on Crystallog raphy, Cambridge, 1839). For simplicity and utility in calcula tion the Millerian notation, which was first suggested by W. Whewell in 1825, surpasses all others and is now generally adopted, though those of Levy and Naumann are still in use.

Although the peculiar optical properties of Iceland-spar had been much studied ever since 1669, it was not until much later that any connection was traced between the optical characters of crystals and their external form. In 1818 Sir David Brewster found that crystals could be divided optically into three classes, viz., isotropic, uniaxial and biaxial, and that these classes corre sponded with Weiss's four systems (crystals belonging to the cubic system being isotropic, those of' the tetragonal and hexagonal being uniaxial, and the orthorhombic being biaxial). Optically biaxial crystals were afterwards shown by J. F. W. Herschel and F. E. Neumann in 1822 and 1835 to be of three kinds, correspond ing with the orthorhombic, monoclinic and anorthic systems. It was, however, noticed by Brewster himself that there are many apparent exceptions, and the "optical anomalies" of crystals have been the subject of much study. The intimate relations existing between various other physical properties of crystals and their external form have subsequently been gradually traced.

The symmetry of crystals, though recognized by Rome de 1'Isle and Flatly, in that they re placed all similar edges and cor ners of their primitive forms by similar secondary planes, was not made use of in defining the six systems of crystallization, which depended solely on the lengths and inclinations of the axes of reference. It was, however, neces sary to recognize that in each system there are certain forms which are only partially symmetrical, and these were described as hemihedral and tetartohedral forms (i.e., half-faced and quarter-faced forms) .

As a consequence of Hauy's law of rational intercepts, or, as it is more often called, the law of rational indices, it was proved by J. F. C. Hessel in 1830 that thirty-two types of symmetry are possible in crystals. Hessel's work remained overlooked for sixty years, but the same important result was independently arrived at by the same method by A. Gadolin in 1867. At the present day, crystals are considered as belonging to one or other of thirty-two classes, corresponding with these thirty-two types of symmetry, and are grouped in six systems. More recently, theories of crystal structure have attracted attention, and have been studied as purely geometrical problems of the homogeneous partitioning of space.

The historical development of the subject is treated in greater de tail by the following: C. M. Marx, Geschichte der Crystallkunde (Karlsruhe and Baden, 1825) ; W. Whewell, History of the Inductive Sciences, vol. iii. (3rd ed., London, 1857) ; F. von Kobel', Geschichte der Mineralogie von 1650-1860 (Munchen, 5864) ; P. Groth, Entwick lungsgeschichte der mineralogischen Wissenschaften (Berlin, 1926).