Ctenophora

CTENOPHORA, a group of extremely curious marine ani mals, mostly pelagic, that is, frequenting the open sea. Their dis tribution is world-wide. They are jelly-fish in the popular sense, but their structure is quite unlike that of the more familiar jelly fish belonging to the phylum of animals known as the Coelenterata (q.v., and cf. HYDROZOA) . The question of the relationship of the Ctenophora to the Coelenterata and other animals is discussed at the end of this article.

The Ctenophora are constructed on the same general plan as the Coelenterata, possessing a single internal cavity only, which opens to the exterior by one main aperture, the mouth. The body is composed of three layers of tissue. The outer layer (ectoderm), covering the surface of the body and lining the throat, is cellular in structure. The inner layer (endoderm), also cellular, lines the internal cavity and produces the sex-cells. Between these layers is a third, the mesoderm, which is jelly-like and contains cells and muscle-fibres.

A common example of a ctenophore is Pleurobrachia, a "sea gooseberry" which under favourable conditions may be taken plentifully in a tow-net in the English Channel. It is an ovoid jelly-fish half an inch or rather more in length, very soft and of glass-like transparency. It possesses two long feathered tentacles, each of which can be withdrawn into a pit in the substance of the body. The animal is an active swimmer, and swims not by repeated contractions of a bell shaped body as do the coelen terate jellyfish, but by the ac tion of a number of minute comb like plates which are attached to the body in eight vertically ar ranged series. These rows of combs are visible in the living animal as vertical stripes, in which a rippling movement, caused by the motion of succes sive combs, can be detected.

The general structure of the animal may be understood by reference to fig. 1. In the mid dle of the more pointed end of the ovoid body lies the mouth. This leads into a flattened throat extending some distance into the interior and opening in its turn into the central cavity of the animal, the in f undibulum. This cavity is not large, but from it there radiate a number of canals which run to various parts of the body and mostly end blindly. All the space between the throat, central cavity and canals on the one hand and the skin on the other is filled in by jelly-like mesoderm, which is so perfectly transparent that the whole sys tem of internal organs is clearly visible from outside. The various canals are very definitely ar ranged, the most important being eight meridional canals which run longitudinally, one beneath each of the eight rows of combs. Each of these canals possesses, in the endoderm lining its outer wall, two concentrations of sex cells—a strip of egg-forming tissue beside a strip of cells which produce spermatozoa.

The other organs are constructed as follows: each of the tentacles is a long solid filament, bearing short lateral branches and composed of ectoderm covering a solid muscular core. At the base it is thickened and is attached to the wall of a deep pocket, lined by ectoderm, which penetrates the side of the animal. The tentacle-bases lie one on each side of the throat in such a way that a line drawn from one to the other would intersect at right angles the longer diameter of the flattened throat. The ectoderm of the tentacles is crowded with cells of a unique description, known as colloblasts. Each colloblast (fig. 1) possesses a dome like portion which is exposed at the surface of the ectoderm and adheres to any prey it touches, and also a spirally coiled con tractile fibre descending into the substance of the ectoderm, whose function probably is to resist the strain put on the adhesive dome by the struggles of a prey and so prevent the tearing off of the dome. There is probably also poison connected with the capture of the prey.

Each of the rows of combs is situated along a meridian of the body and consists of a series of transverse strips of modified ectoderm-cells which cross the meridian at right angles. Each strip bears a comb-like plate whose teeth are made up of large stiff fused cilia; and the cells of one strip are in direct continuity with those of the next along the meridian. The comb as a whole can beat rapidly and repeatedly upwards, and it works in unison with the others in its row.

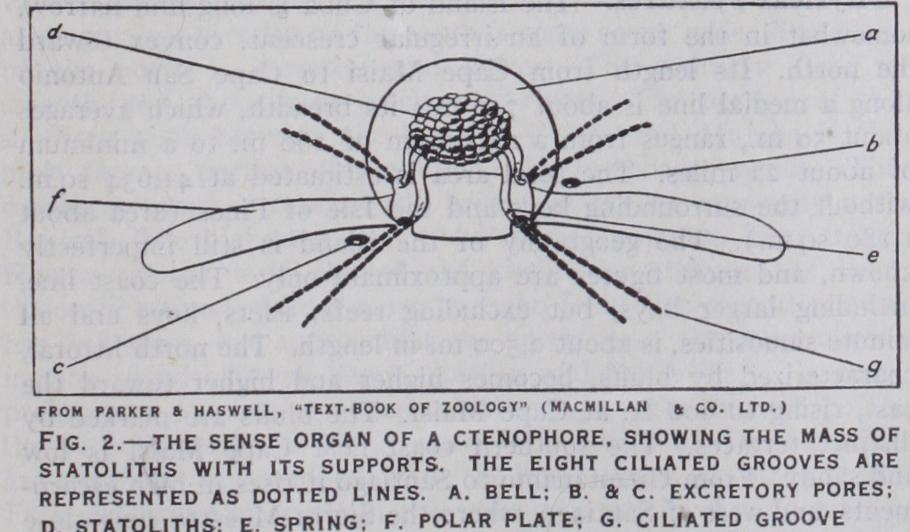

The animal also possesses a complicated sense organ (fig. 2), situated in the middle of the aboral end of the body and consist ing essentially of a small mass of minute calcareous particles (statoliths) supported on four legs composed of fused cilia. The whole structure is roofed in and protected by a little glass-like dome, and from the base of each of the four supporting legs there run out two narrow ciliated grooves, one to each row of combs; these grooves are not nerves but they act in a similar way.

Finally, the ctenophore possesses a diffuse nervous system like that of a coelenterate, consisting of a sub-epithelial network of nerve cells and fine fibrils. Its muscular system consists of muscle fibres traversing the mesoderm and concentrated as longitudinal muscle in the axes of the tentacles, and as sheets near the sur face of the body and under the epithelium of the canals and throat.

The general functions of the ctenophore resemble those of a coelenterate. Respiration and excretion are performed by general surfaces, there being usually no special organs for either function. There are neither blood nor blood-vessels and circulation in the true sense does not exist, the movements of fluid in the internal cavities being due to ciliary action. Food consists of fishes and their eggs and young, other ctenophores, crustacea, medusae and larvae of other animals which are found in the strata of the sea inhabited by the ctenophore. The prey is captured by the tentacles (assisted by their sticky cells) and swallowed by the throat. Digestion is a process involving first the breaking down of the food into particles and secondly the engulfing or ingestion of these particles by individual cells inside which the remaining processes of digestion occur. Both intra- and extra-cellular di gestion appear to take place within the throat, which is not the case in the Coelenterata, and intra-cellular digestion also occurs in the endoderm of the canal-system, assimilated products being apparently carried away by wandering cells. Indigestible waste is voided mainly through the mouth, partly also through pores lying below the apical sense-organ.

The method of swimming in the Ctenophora is most interest ing. A ctenophore of ordinary shape usually swims mouth for wards and the motion is effected by the rows of combs. Each comb lashes sharply upwards (i.e., away from the mouth) and returns more slowly to its previous position ; and the wave of motion affecting successive combs, which traverses the whole vertical row, passes from the aboral end downwards. The ciliated grooves which run from the sense-organ to the rows of combs, and the longitudinal bands of tissue joining the combs, transmit the impulses leading to the effective stroke of the latter. The combs are therefore f ol. ordinary swimming-purposes under the control of the sense-organ, and transmission is through a ciliated epithelium ; but that they are also under nervous control is shown by the fact that in a ctenophore from which the sense organ has been removed mechanical stimuli near the mouth will cause reactions in the combs. The nerve-net of the ctenophore is mainly concerned with its muscles, however.

Space forbids the detailed consideration here of the variations of form exhibited by the Ctenophora. Suffice it to say that al though there is strong adherence throughout the greater part of the group to the fundamental principles of the type of structure described in Pleurobrachia, the general form of the body as a whole undergoes startling modification, the various organs and systems being distorted out of all spatial relationship to that state of affairs. The best example of this is provided by the genus Cestus (fig. 3), where the body has become a flattened translucent girdle, sometimes more than a yard in length, but in which none the less the funda mental ctenophoran structure is easily recognizable. Mention must also be made of a small series of aberrant but most interesting genera, the Platyctenea, in which the structure has become more radically modified. In Coeloplana (fig. 4), which will serve as an example, the animal has assumed a flattened, leaf-like form, astonishingly similar at first sight to that of one of those flattened worms, the Turbellaria (q.v.). Coeloplana adheres to or creeps over the surface of alcyonarian colonies, seaweeds, etc., and although the adult form is so unlike a ctenophore, the larva is much like Pleurobrachia in structure.

The development of the Ctenophora cannot be described here, but it is important to note that the early divisions of the ferti lized egg of a ctenophore are of a different nature from those of a coelenterate egg. If the two cells which result from the first cleavage be separated from one another, each of these may con tinue to develop, but it will form half a ctenophore only; on the other hand, cells similarly isolated in a coelenterate will grow into perfect adults. The same is true in varying degrees of cells sep arated at slightly later stages of division.

With these facts about the Ctenophora before us discussion of their relationships becomes possible. Firstly, the respects in which they resemble that group to which they are usually thought to be most closely allied, the Coelenterata, must be considered. The chief resemblance between the two groups lies in the fact that their general anatomical principle is the same ; both possess a single internal cavity only, opening to the exterior by the mouth, and not comparable to the food canal of a higher animal (small pores of various kinds which exist in both Coelenterata and Ctenophora are obviously of no importance in this connection). In both the tissues are arranged in three layers, cellular ectoderm and endoderm with a jelly-like layer between ; in both the sex products originate in ectoderm or endoderm and are not formed by the intermediate layer even should they subsequently become embedded in it ; and while neither possess true nerves both de velop a sub-epithelial nerve-net. The symmetry of the body is, however, not strictly comparable in the two groups; a typical coelenterate is either radially symmetrical or, if it is an anthozoan, has a bilateral symmetry underlying the radial. It will be seen from the description given above of Pleurobrachia (and by reference to fig. 1), that a ctenophore is radially symmetrical only as regards part of its structure, principally the rows of combs and the meridional canals. Regarded as a whole it can be divided into perfectly equivalent portions along two vertical planes only; i.e., a ctenophore is bilaterally symmetrical about two vertical planes. In this it differs from an anthozoan, which is symmetrical about one plane only if its development be taken into account.

In several other respects a ctenophore differs from a coelen terate. First, the egg of a ctenophore, with its cleavage into cells each of which will form only part of an adult, is markedly unlike the coelenterate egg, as has been already mentioned. Sec ondly, a typical ctenophore swims by means of combs composed of cilia, muscular swimming-motions coming into play on a large scale only in special cases ; but in coelenterates swimming is essentially muscular save in larvae. Again the aboral end of a ctenophore produces an elaborate sense-organ, that of a coelen terate being the least developed end. Furthermore, a coelenterate always possesses those explosive capsules known as cnidae, whereas in the Ctenophora these are replaced by the colloblasts, with which cnidae are not directly comparable. The tentacles of a ctenophore, with their solid muscular axis, are also unlike those of a coelenterate. Capital has been made of the statement that in the development of a ctenophore there is a definite embryonic mesoderm, a set of cells cut off from the endoderm at an early stage and destined to form the axes of the tentacles and to pro vide most of the cells and muscle fibres of the adult mesoderm; whereas a coelenterate develops no such embryonic layer; these statements are, however, queried by certain authorities and can not at present be regarded as de cisive evidence. Epithelio-muscu lar cells (see COELENTERATA) do not occur among ctenophores.

There is lastly the question of the relationship of the Cteno phora to those animals which come next above themin the scale.

Their nearest allies on the up grade are generally considered to be some of the Turbellaria (q.v.), and much discussion has cen tred around their possible affinity with these. We know from the existence of Coeloplana that an animal in certain respects similar to a flat-worm can arise from a ctenophore, and on a number of grounds it is possible reasonably to maintain that the Ctenophora and flat-worms are allied, an idea that recent work on the comparative anatomy and development of the two groups has strengthened. This does not mean that Coeloplana is interme diate between a ctenophore and a flat-worm; and, in fact, it has evolved along lines of its own; but it does mean that there may be ancestral connection between the two groups, though how far back in their evolution we cannot tell. In conclusion, although the Ctenophora resemble both the Coelenterata on the one hand and the Turbellaria on the other, the resemblance is not sufficient for their inclusion in either group.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.--General accounts: G. C. Bourne in E. R. LankesBibliography.--General accounts: G. C. Bourne in E. R. Lankes- ter's Treatise on Zoology 1900,2 ; Y. Delage and E. Herouard, Zoolo gie Concrete, Igo', 2, pt. 2 ; Hickson in Cambridge Natural History, 1906, I.; Krumbach in W. Kukenthal's Handbuch der Zoologie, 1923 25, I. For pictures of Ctenophora see Chun, Fauna u. Flora Golf, Neapel, 188o, I. For recent lists of literature see Kukenthal's Hand buch. (T. A. S.)