Currant

CURRANT. The dried seedless fruit of one variety of the grapevine, Vitis vini f era, cultivated principally in Zante, Cepha lonia and Ithaca, and near Patras, in Greece, and in recent years in California (see GRAPE). The currants of northern Europe and America—so-called from a resemblance of dried black currants to the foregoing—are the produce of several species of Ribes, decidu ous shrubs of the family Saxifragaceae indigenous to Britain, northern and central Europe, Siberia, northern United States, and Canada. There are at least loo species of currants. The Rocky mountains in North America are especially rich in species. The common black currants of Europe are all derived from Ribes nigrum, a native of northern Europe and of northern and central Asia. A few relatively unimportant black currants of America are derived from R. americanum and R. odoratum, natives of North America. Ribes sanguineum, a native of the western coast of North America, is the flowering currant of northern Europe and R. aure um is the chief American flowering currant. The currant seems to have been cultivated first some time before 1600 in the Nether lands, Denmark, and around the Baltic sea. Bushes were brought to settlements in America early in the 17th century. Most vari eties growing in America originated in America. Fay, Wilder, Red Cross, Diploma, Perfection, London Market, and Victoria are the chief varieties. Red Lake is a promising new sort. Important red currant varieties of England are Earliest of Fourlands, Laxtons Perfection, Fay, Rivers Late, Houghton Castle, and Prince Albert. The black currant is extensively cultivated in Europe and to a lesser extent in Canada. Important black currant varieties of England are Baldwin, Boskoop, Seabrook, Laxton, and Daniels September, and of Canada Climax, Kerry, Elipse, Clipper, and Saunders. Both red and black currants are used for making tarts, pies, jams, jellies, etc. Black currants are also used in lozenges, for flavouring, and are occasionally fermented. In 1934 the acre age in England of black currants was reported as 9,5ooac., and of red and white as 3,10o acres. In France 15,000 tons was reported as the crop for 1926.

Currants succeed best in cool, moist northern climates. They are hardy far north in Canada, northern Scandinavia and Russia. The currants and gooseberries are the chief agencies in the spread of the white-pine blister rust, a destructive disease of the five leaved pines in Europe and America. The common garden black currant is the favourite host of the blister rust. Because the white pine is one of the most valuable timber trees of the United States the black currant has been declared a menace and is not grown in most of the United States. Furthermore, the culture of all cur rants and gooseberries has been prohibited in many sections of the United States. The Viking red currant (called Red Dutch in Norway) is a vigorous variety immune to the blister rust and is being tested in northern United States for its horticultural value. The Red Holland variety of Germany and Switzerland is also im mune to this disease. The currant maggot, for which there is no known control, infects the fruit so badly in parts of western North America that this fruit is not grown. The attacks of the currant worm may defoliate the plants in the spring unless controlled by using powdered hellebore, diluted 5 to 10 times with flour or air-slaked lime, or as a spray, with 'oz. to 'gal. of water.

The black currant is subject to the attacks of a mite, Phytop tus ribis, which destroys the unopened buds. The infested buds, recognized by their swollen appearance, should be picked off and burned. Reversion has been found to be a virus disease and is controlled by destroying affected plants.

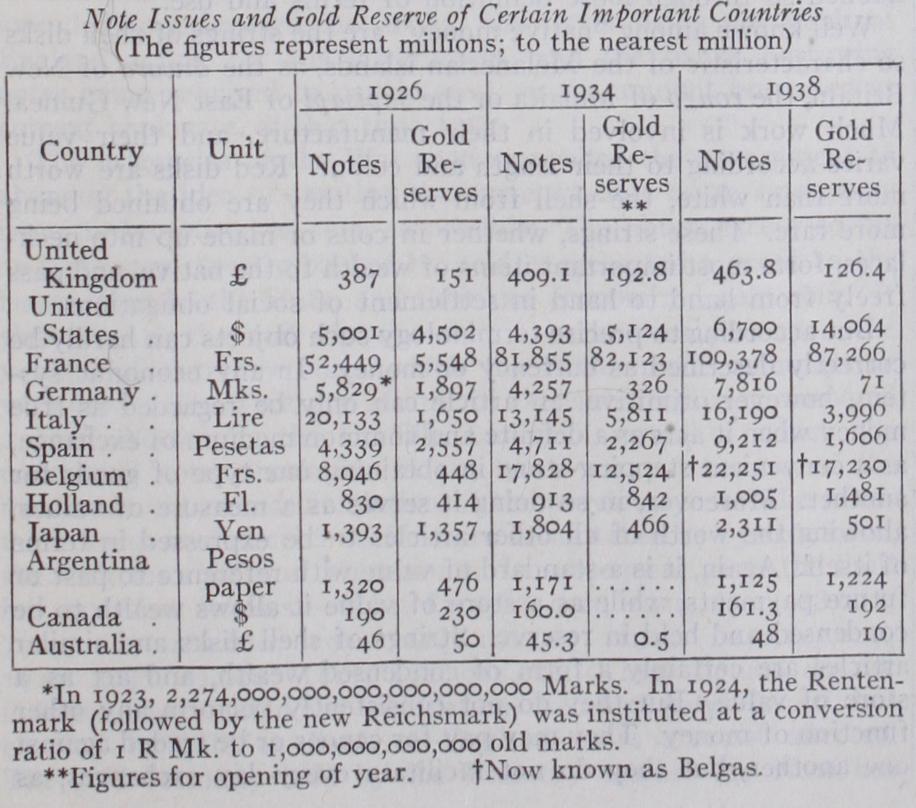

Clay and silt soils are preferred for growing currants. They are propagated almost entirely by means of cuttings made from vigorous shoots of the current season's growth. The cuttings, 8 to 12in. long, are usually taken in the autumn and set in the nursery immediately or buried in sand till spring and then set 3 to 6in. apart with not over two buds left above ground. In the plan tation they are set 4 to aft. apart in rows 6 to 8ft. distant. Under intensive cropping currants are planted under grapes, peaches, cherries, apples, and pears because they stand shade better than most plants. (G. M. D.) significance of the term "currency" has undergone considerable change within the past few years. As originally employed by classical British writers, it was made to include all current circulating media, both coin and paper. "The currency of a great nation" says Adam Smith, ". . . consists almost entirely of its own coin." This way of applying the word was maintained practically down to the time of Jevons, who em ploys it in practically the same sense in his "investigations in Currency and Finance." The practice later developed ordinarily of prefixing the word "paper." Paper currency was then synony mous.with bank notes, in those countries where no government issues had been made, while in others, e.g. the United States, bank notes were issues of banks ; and "currency" included the so called "greenbacks" or legal tender notes. American usage fre quently tended to confine the application of the term "currency" to non-bank notes, thus limiting it to government legal tender. While it cannot be said that an absolutely established usage pre vailed at the opening of the twentieth century, prevailing practice used the word "money" to include only "hard money," both standard, e.g. gold, and "representative money"—e.g. in the United States, the silver dollar. Bank notes, as the name implied, were issues of banks, while currency was prevailingly used to indicate any kind of paper habitually employed as a medium of exchange. "Time" paper, including cheques, bills, drafts, and other obliga tions not payable at sight were not included. What is now called "deposit currency" represented by cheques, payable at sight, like wise, was outside the "currency" classification. During the World War, the free movement of precious metals was generally sus pended; and great changes took place in monetary use. Credit assumed a commanding position. During the latter part of the war, and since its close, usage has gradually changed. Today, the term "money" is widely used to include everything that possesses current availability in effecting the exchange of goods. Thus, the League of Nations in its recent "Memorandum" on banking speaks of : "Currency composition,—the word `money' is used in the very wide sense of means of payment . . . [and] includes not only notes and coin but also sight deposits. . . ." A general discussion of the problems of currency will be found in the articles "Money," `Banking and Credit" and "Inflation and Deflation." The following is an account of the gradual de velopment of the present currency situation among the chief nations just before and since the World `'Var. Gold holdings of the several nations are given under the head "Gold Reserves," which is here taken to mean not only technical reserves in banks but the entire supply of standard money in the country. The fig ures for reserves are thus furnished because of the fact that, at least in theory, gold continues to be the basis of international ex changes and settlements.

Normal Volume of Currency.

The idea of a "normal" volume of currency is based upon the assumption that outstand ing paper either represents an irreducible minimum of circulatory demand, which may be occupied either by "hard" money, or by corresponding legal tender paper (as in the case of American pa per currency below $5) or else, that in its larger denominations it represents an increase in the demands of "business" for the "means of payment." Of course, any such notion of a "normal" volume presupposes a given price level. At a specified price level, and with the assumptions just before enumerated, fluctuations in the amount of currency then more or less represent changes in the activity of business, and thus become an interesting commentary upon, or "index" of, the general movement of trade.The idea of what is called "elastic" currency is that of pro viding new issues of notes upon a security or basis which repre sents nothing more than the degree of solvency of business houses which are engaged in selling or buying commodities then on their way to consumption. The economists of a generation ago regarded this element of elasticity as the fundamental require ment in a good bank note circulation and were inclined to the view that, while the issue of government notes for the smaller denominations representing a business demand which was com paratively steady, might be tolerated, it was only through a busi ness organization (the bank itself) so conducted as constantly to test the liquidity of business, that a satisfactorily "elastic" and serviceable note currency could be provided. The rapid substitu tion of the check and deposit system for notes has led some econo mists to extend this doctrine of "elasticity," so as to take in bank credit and, as a corollary, to view elasticity in the note issue itself as only an incidental and non-essential criterion of paper issues. The enormous extension of notes shown in the table already fur nished is largely the outgrowth of changes in prices due to altera tion in the weight or value of the underlying unit of money in the various countries. With some modifications the same would be true of the growth of bank deposits—a subject, however, not dealt with in this article.

Idea of "Inflation..

For many years past, the concept of "inflation" has played a part, although at times a rather vague one, in economic discussion. During the early years of the de velopment of the idea, the terms "inflation" and "inflation of cur rency" were often used practically synonymously,—inflation being regarded as a special phase of currency difficulty. Later theory has shown that inflation is a concept no more applicable to the note currency than to the creation of bank credit in the form of deposits, but popular opinion has continued to associate the idea of note expansion with the conception of inflation. Generally speaking, a note inflation is regarded as the issue of notes, either for the purpose of paying public expenses or, as in the case of the banks, as a basis for conducting lending operations without hav ing behind such issues a form of transaction or of security which will undoubtedly enable the issuer to redeem in a satisfactory form upon demand. The popular tradition that great enlargement of the currency means a corresponding rise in goods prices is Tar from being absolutely true, and depends for its validity upon a variety of modifying conditions. Still, it has nearly always been true that every great expansion of purchasing power, whether with the cooperation of other factors or not, has tended to bring about irredeemability, or, when the currency was confessedly ir redeemable from the start, has reduced the purchasing power of the unit,—the result being an advance in prices. More complete analysis has shown that "inflation," in the true sense of the word, is a phenomenon of production, the changes of prices which are associated with it being rather the cause of excessive currency issue than the effect thereof. The experience of the United States has been conclusive on this score, enormous increases in media of exchange during the years 192o-1929 being accompanied by a declining price level instead of an increasing one, while parallel examples may be found in other countries. The latter theory has also emphasized the fact that the influence supposed to proceed from currency inflation upon the price level is quite as vigor ously, if not more vigorously, exerted by corresponding expansion of bank credit or deposits carried by the banks.By deflation is meant the retirement of inflated currency (or credit) and the restoration of the volume of a circulation to the point at which it can be effectively redeemed, either in the stand ard of value or in goods that are currently demanded, at "normal" prices. The term "reflation" has been recently invented by some American economists and has been used to signify the restoration of a currency and credit circulation to a former volume, presum ably with the intention of restoring a former level of commodity prices.

A major cause of what is called inflation during the years has been the adoption of governmental policies designed to provide work for the unemployed and paid for either by the issue of paper currency or by the discounting at banks of govern ment obligations whose proceeds were represented on the banks' books by deposits, and were then drawn upon by the public au thorities in order to meet their obligations.

Currency and Prices.

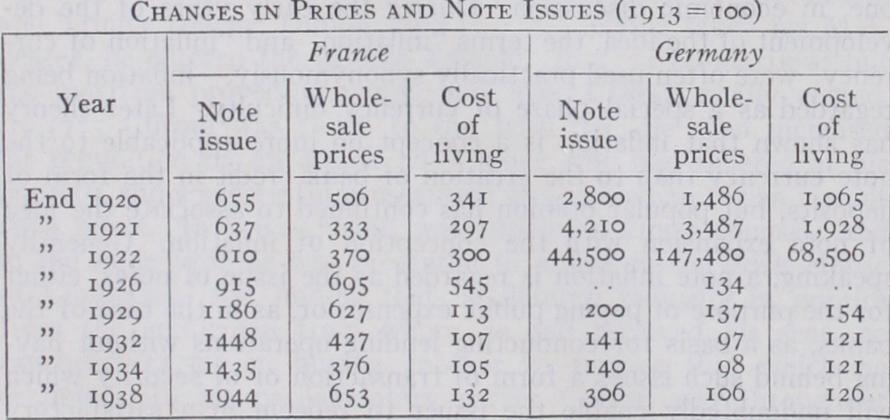

The assumption that the more cur rency and credit there are in existence, the higher are commodity prices, is a view which logically represented a development of the "quantity" theory of money. If taken with the original quali fication always imposed by the classical economists "other things being equal," it is likely to be the statement of a truism. The trouble with it at best is that it merely states a fact and does not indicate the dynamic factors that tend to produce price changes, either upward or downward. The unsatisfactoriness of this doc trine of a supposedly close relation between volume of currency and prices of goods has become greater as economists have tended to substitute a relationship between prices and credit or prices and "currency" for the older and simpler monetary relationship. To day, the notion of direct correlation is definitely discredited and few still assert that any causal relationship exists between these factors. Nevertheless, as already stated, the same conditions which led to inflation in the "production" sense of the word, are likely to lead to expansion of note currency, if for no other rea son than because the rising scale of prices makes a more ample hand-to-hand medium of exchange convenient. In the following table, recent changes in prices and note issue for two representa tive countries where note expansion has been pronounced since the World War are compared.

The correspondence between prices and currency supplies as thus statistically indicated, is rather remote, but even if it were close a direct question would still remain, whether such corre spondence was the result of extraneous factors or whether some interrelation was the cause of price change. In the period covered by the table, many factors of first importance have been operat ing upon prices and there has probably never been a time when "other things" were less likely to be "equal" than during these very years.