Cyanide Process

CYANIDE PROCESS. When the cyanide process was in vented in 1887 there was pressing need for improvement in the treatment of gold ores. The industry, after languishing for many years, had received a fillip from the discovery of the Rand gold field and was attracting great attention. The mining of ores was by no means inefficient, but extraction of the gold from them was poor and behind the times. The old amalgamation process (q.v.) was cheap but in general could only extract some 6o% of the values, and most of the finely divided gold, as well as the gold contained in minerals such as pyrites and other sulphides, escaped in the tailings. Many ores had been discovered which could not be treated by amalgamation or were too poor to pay for working. Smelting, although effective, was costly and required the supply of large quantities of rich ore, together with lead ore and cheap fuel at no great distance from the gold mines. Metallur gists were busily engaged in the search for new methods and almost any proposal was eagerly seized upon and tested. It was the paradise of the bogus process-monger. Many new processes, including novelties in amalgamation, were found to be worthless or of limited scope.

The proposal to use cyanide of potassium as a solvent for gold in ores is almost the only instance on record of an invention of vital importance to an industry being made to order. It was put forward by J. S. MacArthur and R. W. and W. Forrest and was received at first with derision, partly because the chemical was rare and had been little studied. Cyanide was best known at the time as a deadly poison, although small quantities were used in electroplating and in photography.

However, it was soon found that the proposal was a sound one. It was tried in New Zealand in 1889 and in South Africa in 1890 and before long was recognized as the new process for which everyone had been seeking. At first it was used mainly on the tailings from amalgamation in the Transvaal, but it was applied later to both gold and silver ores without previous amalgamation, and this practice had become the general rule by 1925.

In the process, pulverized gold ores or the tailings from amalgamation are mixed with a dilute solution of potassium cyanide (KCy) or sodium cyanide (NaCy) in water. The gold and silver are dissolved and the solution is separated from the ore by filtration. The clear solution then flows through a mass of zinc shavings, when the gold and silver are precipitated and appear on the surface of the zinc as a black slime, while some zinc is dis solved. The black slime is purified, melted down and cast into bars of gold and silver. In modern practice the zinc shavings are replaced by zinc dust.

The chemical action is complicated but need not be discussed here at length. The gold is not dissolved without chemical change, as sugar is dissolved in water. It is converted into cyanide of gold and is dissolved as a double cyanide of gold and potassium. When chemical symbols are used, the dissolving of the gold is repre sented by the following equation :— Among the involved chemical actions which take place there is one which should be borne in mind, and that is the part played by air in dissolving the gold. It is necessary to ensure the con tinuous presence of oxygen at the surface of the particles of gold or the action stops altogether.

Crushing and Cyaniding the Ore.

Gold ores are generally crushed in cyanide solution instead of water. The result is that the gold begins to be dissolved at once, and the dissolving con tinues throughout the succeeding stages until filtering is com pleted. A variety of machines are used for crushing, among which may be mentioned the stamp battery (see AMALGAMATION) .When the ore has been reduced to a maximum size of about in diameter it is delivered in to tube mills (fig. 1), for further grinding. A tube mill is a long iron cylinder placed in a hori zontal position and made to re volve on its own axis. It is half filled with flint pebbles or pieces of unbroken ore, which roll over each other as the mill revolves and grind the ore to a mixture of sand and slime. It is continuous in action. The ore enters cease lessly at one end and passes out at the other.

The product of the tube mill is next "classified" or separated nto sand and slime. One type of classifying machine much used in South Africa is the Cone Classifier (fig. 2) . This is kept full of water and the pulp is run in at the top. The coarse sand settles and passes through a nozzle at the bottom ; the fine slime over flows at the top with most of the water. The coarse sand is returned to the tube mill to be ground again and the product is fed once more into the classifier. The ore is thus all ground to slime in the end, as the only part which goes forward to other machines is the overflow from the classifier (fig. 3) . This method of work is called "all-sliming." At this stage of the operations the dissolving of the gold is assisted by the use of agitating vats. One of the most ingenious of these is the Pachuca tank (fig. 4), so called because of its use on silver ores at Pachuca in Mexico. Air is forced into the cen tral tube A at the bottom and bubbles up the tube, carrying the slimed ore with it. The slime overflows at the top of the tube and, passing down in the tank outside, enters the tube at the bottom and is carried up again. Aeration and mixing continue until the gold is dissolved.

Filtration and Gold Recovery.

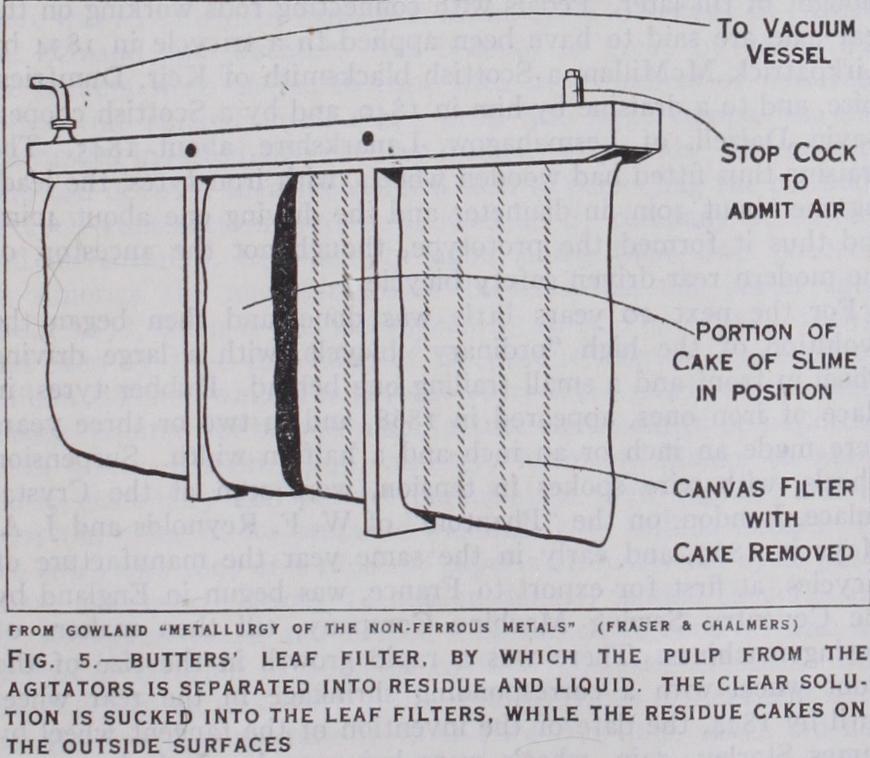

After the gold has been dissolved in the agitators the mixture is pumped into a filtering tank and the solution is separated from the residue by means of leaf filters. A single filter leaf (fig. 5) is a canvas bag, wide and deep but nearly flat. It may be pictured as an empty sack. In the Butters leaf a vacuum is created inside the bag so that the clear liquid is sucked through the canvas into it. The solids form layers or cakes of slime on the outside surfaces. When the cakes have grown to about sin. thick, they are detached and the filter ing is renewed. A large number of filter leaves are clamped near together in a parallel position and the whole frame of filter leaves, or "basket" as it is called, is im mersed in the pulp to be filtered. In some other leaf filters the pulp is forced under pressure into the interior of the leaf or bag and the clear liquid passes through the canvas to the outside, leaving the solids inside. This variety of filtering is called "filter-pressing." An alternative and older method of separating the gold-cyanide solution from the ore-slime is by decantation. The mixture is allowed to settle in large vats and the clear liquid is drawn off from the top. Lime is added to the charge to hasten the settling. An improvement consists in continuously introducing a slow cur rent of clear water at the bottom and allowing it to overflow at the top (counter-current decantation). In this way the ore-slime never settles but remains in suspension in the water in the vat and is gradually washed clean.For the recovery of the gold from the cyanide the dissolved air is first removed from the clear solution by applying a vacuum to thin streams of the liquid (Crowe process) . The solution is then mixed with zinc dust and the gold precipitated as black slime (not to be contused with the ore-slime mentioned previously), while most of the zinc is dissolved. The gold-slime is then filter-pressed in leaf filters and the clear cya nide solution separated in them is conveyed to a storage tank for use again after it has been re aerated. The gold-slime is purified by furnace methods and is finally melted and cast into bars.

One of the most striking fea tures in the cyanide process is the extreme dilution of the solutions. In South Africa the cyanide solu tions are kept as far as possible at a strength of only 0.027% (0.S4 lb. per ton), and in 1922 the consumption of cyanide was only about 0.27 lb. per ton of ore. The total cost of treatment by a modern plant is 3s. 6d. per ton. This is remarkably low consider ing the complexity of the process, which can hardly be realized from the incomplete outline presented here. About 98% of the gold is extracted.

Silver ores are treated similarly to gold ores, but the solutions are stronger, generally containing from o• 1 % to 0.5% of cyanide.

In places where the amalgamation process still lingers, as in India, gold ores are crushed in water, not cyanide solution. The all-sliming method is not used, but instead the sands and slimes are cyanided separately. The sands are charged into large cir cular vats. Cyanide solution is pumped on to the top and sinks downwards through the sand, dissolving the gold as it passes. It runs out at the bottom through a filter bed of coarse sand covered with canvas. The oxygen is supplied from that dissolved in the solution and from the air held in the porous ore. The air supply may be renewed by draining the charge dry. Similar methods were in use in South Africa before 1925.

In conclusion it may be observed that the cyanide process was responsible for a very large proportion of the world's production of gold and silver in recent years, and that the mining industry is well satisfied with its results.