Cyclostomata or Marsipobranchii

CYCLOSTOMATA or MARSIPOBRANCHII, a group of vertebrate animals that includes the lampreys and hagfishes; formerly these were placed among the fishes, but are now generally regarded as forming a class apart. The Cyclostomata are naked, eel-shaped animals, without paired fins; the mouth is not pro vided with jaws, but there is a very muscular protrusible tongue, which is armed with horny teeth, and works like a piston, rasp ing off the flesh of the fishes on which these animals prey. The gills are vascular ridges on the inner walls of a series of separate sacs enclosed in muscular pouches. The gill-sacs communicate in ternally with the pharynx and open to the exterior either directly or by means of ducts. The olfactory organs are united and open into the pituitary canal, the ex ternal aperture of which appears as a single median nostril.

Relationships.

It is gener ally considered that the condition of the olfactory organ in Cyclos tomes is secondary, and that other vertebrates with the olfac tory organs and nostrils paired are more primitive in that re spect. Whether the absence of jaws and of gill-arches is primi tive or not has been disputed, certain structures in Myxine having been interpreted as modi fied branchial arches. Quite re cently, however, the Anaspida and Cephalaspida, ancient groups known only from Palaeozoic fos sils, have been proved by Kiaer to be closely related to the Cyclos tomes, and the wonderful researches of Stensio on the Cephala spida have shown that in them the first gill-sac was situated in advance of the position occupied by the jaws in other vertebrates. It follows that the Cephalaspida had no jaws and were not derived from animals with jaws, as in other vertebrates the modification of a pair of gill-arches into jaws has entailed the disappearance of the gills in front of them. The difference between the Cyclosto mata and other vertebrates in the structure of the mouth and gills is therefore fundamental, and they may properly be grouped with their allies as Agnatha (without jaws) and opposed to the jawed vertebrates, collectively termed Gnathostomata. Another char acter of the Agnatha is that the ear has only two semi-circular canals (united to form one in the Myxinidae), the horizontal canal found in all Gnathostomata being absent.Of great importance in the question of relationship is the struc ture of the larva of the Petromyzonidae, which is so different from the adult that it was formerly considered to be a distinct genus and was given the name Ammocoetes. It is of remarkable interest that this larva not only breathes and feeds in the same way as Arnpliioxus and the Tunicates, a current of water produced by ciliary action entering the mouth and bringing with it minute organisms that are entangled in a mucous secretion, but it agrees with them in the structure of the pharynx which has a ventral longitudinal groove that secretes a sticky slime. This similarity to the lower Chordata is additional evidence that the Cyclo stomata are a primitive group.

Classification.

Leaving out of consideration for the present the fossil Agnatha, the cyclostomes comprise two well-separated sub-classes, each with a single family, the Hyperoartii (Petro myzonidae) and the Hyperotreti (Myxinidae), the diagnostic char acters of which are as follows:— Sub-class 1. Hyperoartii.—Nasal opening on upper surface of head; pituitary canal closed internally. Eyes well-developed (in the adult). Mouth terminal, in the middle of a toothed, funnel shaped sucker. Gill-sacs, seven, communicating directly with the exterior and internally with a suboesophageal chamber that opens in front into the pharynx (in the larva opening directly into pharynx) . A firm, extra-branchial skeleton forming a basket-work. Eggs small. Development with larval stage and metamorphosis into the adult.

Sub-class 2. Hyperostreti.

Nasal opening terminal; mouth on underside of head, a little behind nasal opening, without sucker; pituitary canal opening into pharynx. Eyes vestigial. Mouth and nasal opening each with two pairs of tentacles that are supported by cartilages. Tongue very large. Branchial sacs five to 14, well behind head, communicating internally with the pharynx. Branchial skeleton greatly reduced. Eggs large. De velopment direct.

Anatomy.

In general the anatomy of the cyclostomes is much as in selachians and fishes, but there are many primitive features. The vertebral column is represented by the notochord and its sheath, with the addition in the Petromyzonidae of paired carti lages representing neural arches; the cartilaginous brain-case is incomplete, especially in the Myxinidae. The brain is of a primi tive type. In the Petromyzonidae there is a pineal eye, which lies beneath the skin but is quite visible. In the Petromyzonidae the kidneys are compact glands, but in the Myxinidae they are extremely simple with separate tubules opening into the kidney duct. In the Myxinidae there is on the left side, immediately be hind the gill-sacs, a duct leading from the pharynx to the exterior, possibly serving for the intake of the respiratory current when the head is buried in a fish that is being devoured. In the Petro myzonidae the dorsal and ventral roots of the spinal nerves remain distinct, but in the Myxinidae they unite.

Distribution.

The Petromyzonidae (Lampreys, q.v.) in habit the seas of the north and south temperate zones; they enter fresh water to breed and some are permanent residents in fresh water. There are about 20 species belonging to eight genera, which are distinguished especially by the structure and arrange ment of the horny teeth on the sucker, on the tongue, and above or below the mouth-opening. Mordacia and Geotria are southern, with eight species from Australia, New Zealand, and Chile; the other genera are northern. In Petromyzon of the North Atlantic and Mediterranean the sucker is covered with radially arranged teeth, as it is in Ichthyomyzon of eastern North America, Endontomyzon of Transylvania, and Caspiomyzon of the Caspian sea. In Entosphenus and Lampetra the teeth on the suckers are scattered. Entosphenus has three species in North America and one in Japan ; it is a most curious fact that the Japanese species has been recorded from Arch angel, thus agreeing with the Japanese herring, which is also found in the White Sea. These are remarkable and as yet unex plained examples of discontin uous distribution. The three British species are the sea lam prey (Petromyzon marinas) which is found on both sides of the North Atlantic, the lampern or river lamprey (Lampetra fluviatilis) which extends through Europe and Siberia to western North America, and the brook lamprey (Lampetra planei), a strictly fresh-water species of Europe, Siberia and Japan. The Myxinidae (hag-fishes, borers or slime-eels) are strictly marine and generally inhabit rather deep water; they are mainly found in temperate seas. Heptatretus (Bdellostoma) has six to 14 well-separated gill-openings on each side. There are ten species from Japan, Alaska, California, Chile, New Zealand, and South Africa. Paramyxine, with a single species from Japan, has the six gill-openings close together, and thus leads to Myxine, in which the ducts from the gill-sacs unite and have a single external aperture. Myxine glutinosa is found on the Atlantic coasts of Europe; other species are known from Japan, South Africa, Chile, and Patagonia, and one has been found in the tropics, off the west coast of Panama, at a depth of 73o fathoms.

Natural History.

With their sucker the lampreys attach themselves to fishes, which they devour, sucking the blood, and scraping off the flesh by means of the toothed tongue. When they are so attached, and perhaps also when they are swimming, the respiratory current, produced by the expansion and contraction of the gill-sacs, both enters and leaves by the external gill-open ings. The sea lamprey attains a length of aft. and a weight of 5 lb. In the spring or summer it enters rivers to breed, often stealing a ride by fastening on to large fishes bound in the same direction. The males go first and each selects a place where the stream is fairly rapid and the bottom is sandy but strewn with pebbles; here he clears a sandy space by fastening on to stones with his sucker and moving them down stream; on joining him, the female helps; she then secures herself by her sucker to a large stone near the upper end of the "nest," and her mate attaches himself to her in the same way near the head ; they then stir up the sand with vigorous movements and the eggs and milt are deposited; particles of sand adhere to the eggs, which sink to the bottom of the nest. The pair now separate and remove stones from above the nest, so that sand is carried down and covers the eggs. After spawning, the lampreys die ; they are emaciated, their intestine is atrophied, and they are so weakened that recovery is im possible.In ten to 15 days the larvae are hatched, and about a month later, when they are about half an inch long, they move down stream to a place where the water runs slowly and burrow in the sand or mud. The larvae, or prides, differ greatly from the adults ; they are toothless, with a small, transverse lower lip and a hoodlike upper lip, and the entrance to the mouth is guarded by a number of fringed barbels that form a sieve. The eyes are rudi mentary and concealed, and the small gill-openings lie in a groove.

Each larva lives in a tube that it forms in the sand or mud, open so that water enters freely. They feed on minute organisms which are brought into the mouth by a current of water produced by ciliary action. After living in this way for three or four years, and when they are kin. to 6in. long, they change into the adult form ; first the eyes appear, then the lips join and grow out to form the sucker, the barbels are reduced to little papillae, the teeth develop, etc. The transformation takes about seven weeks, and when it is completed the young lampreys make their way to the sea. The lampern grows to a length of i6in. ; it has a similar life history, except that some never venture to the sea. Several couples share in making and using a nest. The brook lamprey grows to only 8in., and never goes to the sea; it is said to spawn soon after the metamorphosis, and perhaps never feeds as an adult.

The Myxinidae, known as hagfishes, slime-eels, or borers, are more thoroughly parasitic than the Petromyzonidae and bore right into the fishes on which they prey, devouring all the soft parts and leaving only the bones inside the skin. They are espe cially fond of attacking fishes caught on hooks or in nets, and in some districts are a great nuisance to the fishermen. As they read ily take a bait, it seems that they may also seize and eat smaller animals. They have a row of glands on each side of the body capable of producing great quantities of slime, no doubt a valu able protection against attack. The current of water for breathing generally enters through the pituitary canal. There is some evidence that Myxine glutinosa is hermaphrodite, each individual being a male in early life and a female later on, but in the Cali fornian Heptatretus stonti the sexes are distinct. The eggs are large, heavily yolked, and when laid are protected by a horny capsule, oval or sausage-shaped, in some species nearly an inch long. These become attached to each other by groups of anchor filaments at their ends, and form clusters that lie on the sea bottom. The whole development takes place in the egg capsule, and the newly hatched young is essentially similar to the adult.

Palaeontology.—Four distinct groups of Palaeozoic fish-like vertebrates from the Silurian and Devonian formations of Europe and North America, appear to be related to the cyclostomes, and may be grouped with them as Agnatha.

The Pteraspida (Heterostraci) had a depressed head and body and a short tail, with a heterocercal tail fin. The mouth was subterminal and the eyes were small and wide apart ; there was a single external gill opening. The body was covered with den ticles (Coelolepidae) or with bony plates and scales (Pteraspidae, Drepanaspidae). Impressions on the under side of the dorsal shield of Cyathaspis show that there was a series of gill-sacs and that the nasal organs were paired but contiguous.

The

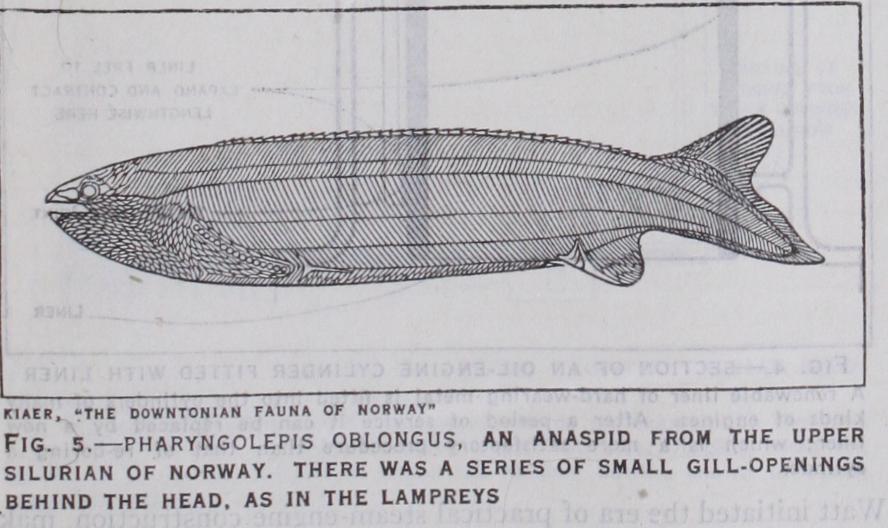

Anaspida were of normal fish-shape, with peculiar scales and with a reversed heterocercal caudal fin. As in the lampreys there was a series of gill-openings on each side. The mouth was terminal, the eyes were lateral, with a pineal eye between them and a median nostril a little in front of it on top of the head. Principal genera Lasanins, Birkenia, Rhyncholepis, Euphanerops.

The Cephalaspida (Osteostraci) differ from the Anaspida in having the head depressed, covered by a bony shield, with the eyes on top of the head and the mouth ventral. The caudal fin was heterocercal. Principal genera Cephalaspis, Tremataspis.

The Cycliae include the single genus

Palaeospondylus, a small animal, up to tin. long, from the middle old red sandstone of Caithness, remarkable for having well developed annular verte bral centra. The brain-case has an anterior opening, surrounded by a circle of projections comparable to the cartilaginous ten tacles of Myxine. Stensio interprets this as the unpaired nasal opening, and compares the prominence on each side of the front end of the skull with the subocular arch of the cyclostomes, and certain elements below it with the inter-branchial ridges of the Cephalaspida. Stensio's interpretation is probably correct, but Sollas and Sollas had previously considered the anterior promi nences to be paired olfactory capsules and the elements below the skull to be branchial arches; they suggested that Palaeospon dylus might be a selachian.

The evidence is clear that the Anaspida and Cephalaspida are closely related to the Petromyzonidae; Stensio, regarding the terminal position of the nasal opening as primitive, groups the Pteraspida and Cycliae with the Myxninidae. This is rather spec ulative, for there is no evidence that any of the fossil groups had the toothed protractile tongue of the modern cyclostomes. The elongation of the nasal canal in Myxine, and its terminal opening, may be secondary, related to its inspiratory function, and to the importance of smell to these sightless creatures.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-B.

Dean, "Embryology of Bdellostoma," Festschrift Bibliography.-B. Dean, "Embryology of Bdellostoma," Festschrift C. von Kuppfer (Jena, 1899) ; W. J. Sollas and I. J. B. Sollas, "Palae osopondylus," Phil. Trans. R. Soc., B. cxcvi. (1903) ; J. Dawson, "Feeding and Breathing of Petromyzon," Biol. Bull. ix. (19o5) ; T. W. Bridge, "Fishes," Cambridge Natural History (19o4) ; F. J. Cole, "Morphology of Myxine," Tr. R. Soc. Edinburgh (1905-1926) ; E. S. Goodrich, Lankester's Treatise on Zoology, pt. ix., "Cyclostomes and Fishes," (1909) ; C. T. Regan, Systematic Revisions: vii. Petromy zonidae, ix. Heptatretus, xi. Myxine, Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. (1911-13) ; A. N. Severtzov, Evolution des Vertebras inferie:crs (1916-17) ; J. Kiaer, "Anaspida," Vidensk. Selsk. Skrift. Kristiania (1924) A. Stensio, Cephalaspida, Norske Vidensk. Akad., Result. norske Spitsbergens ex pedit., No. 12 (1927), with good bibliography and full discussion.(C. T. R.)