Cylinder in Engineering

CYLINDER IN ENGINEERING The cylinder is one of the primary mechanical elements used in numerous kinds of prime movers, compressors, pumps, and pneumatic and hydraulic appliances. The earliest cylinders were employed in what were termed fire-engines, which operated by the production of a partial vacuum beneath a piston. Huygens in 1678 exploded gunpowder below the piston; with the expulsion of the gaseous products and the cooling of the remainder a vacuum was produced for the piston to descend by atmospheric pressure. Papin in 1690 applied steam in a crude fashion, and Savery and Nowcomen carried developments further (see CONDENSER), but Watt initiated the era of practical steam-engine construction, mak ing double-acting cylinders in which steam drove the piston to and fro, the principle remaining unchanged to-day. Later im provements involved better methods of manufacture, the use of higher steam pressures and superheated steam, as well as of the expansive energy in successive cylinders, in compound, triple-ex pansion, and quadruple-expansion engines. Now these multi-cyl inder types are challenged by a single-cylinder engine, the "Uni flow," with its method of exhausting through central ports instead of at the ends of the cylinder as usual. Great efficiency results from the fact that condensation losses are reduced by the absence of alternate rushes of hot live steam and cooled ex haust steam over the cylinder surfaces.

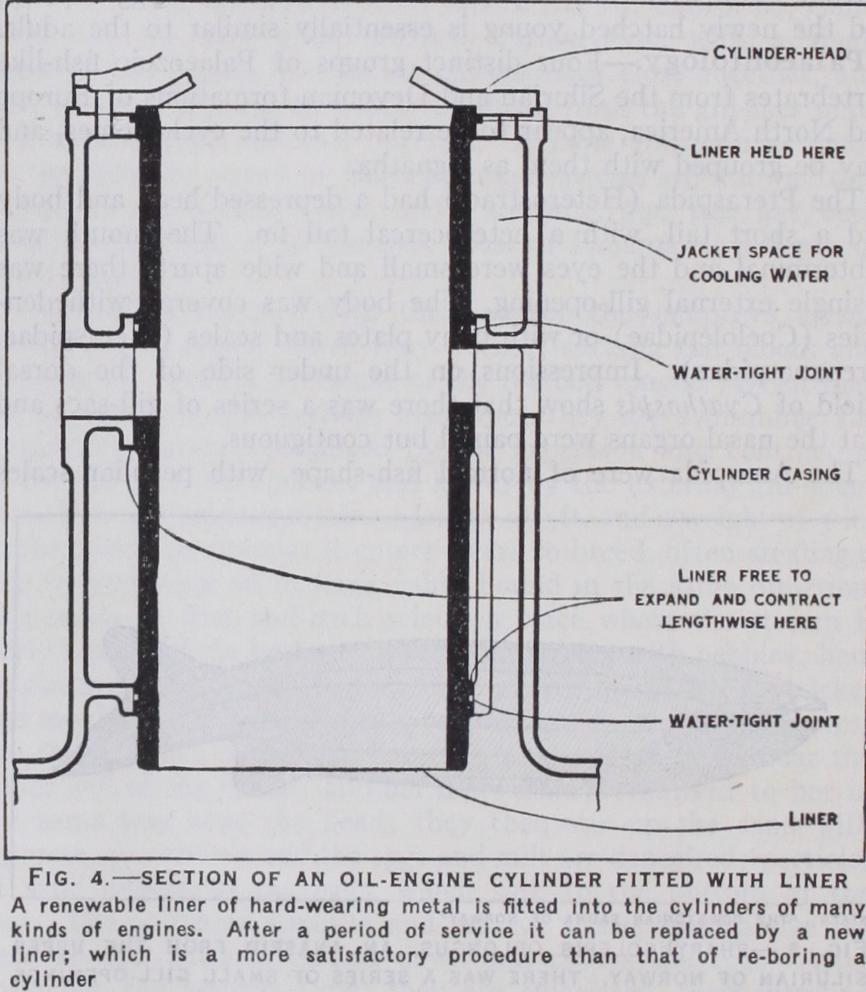

Steam cylinders must be kept warm by lagging with non-con ducting substances packed around the exterior, or by passing live steam around in a jacket. In internal-combustion engines and compressors the opposite need must be satisfied. The temperature must be kept down in order that the lubricating oil may keep in a working condition, and the parts maintain their shape. Air or water cooling systems deal with this problem (see COOLING SYS TEMS). But in any class of cylinder the risk of distortion must be guarded against by careful design ; no very thick parts must be adjacent to thin ones, or expansions and contractions will be un equal, and leakages of steam or gas or vapour will occur. The strongest construction is in the Diesel engines, which have to act as powerful air-compressors, and then withstand the ensuing strong power stroke. The liner is an important constructional feature in great numbers of cylinders ; it is a very plain tube of close-grained, hard-wearing, iron or steel, fitted into the cylinder, and often held at one end only. leaving the remainder of the length to expand longitudinally (fig. 4). When much worn the liner can be taken out and a new one inserted. It is also convenient when employing aluminium cylinders for lightness, steel liners taking the wear of the piston. Liners of gun-metal or phosphor-bronze are fitted in some kinds of hydraulic machinery (e.g. pumps) to pre vent rusting, and the rams may be of stainless steel for the same reason. When cast-iron does not afford sufficient strength, cast steel is chosen, particularly in hydraulic work, while if pressures are very high, as in some pumps, the cylinder bodies are bored out of solid blocks of forged steel.

Thicknesses range between remarkable extremes; on the one hand are the -A in. walls of aero-engines, and on the other the 9in. cast-steel walls of a Davy 12,000 ton armour-plate press. Sound metal is particularly important in cylinders, and careful selection and casting of the metal are imperative. Many steam cyl inders and others including those for hydraulic presses, are cast with a large extra lump of metal at the top, termed head-metal, the dross and scoriae rising into this. When the casting is taken from the mould, this lump is cut off, leaving pure sound metal through out the cylinder.

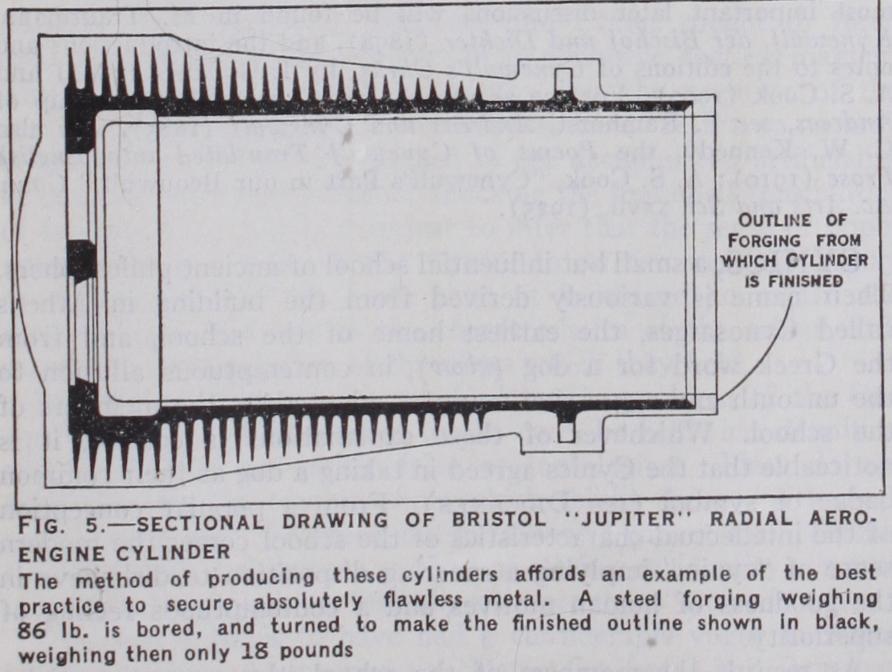

Multi-cylinders are used to a great degree in steam-engines. compressors, pumps,' and motor and aero work. They are either built up by bolting together, or cast en bloc, the latter method being preferable from the point of view of rigidity and compact ness. Aero-cylinders are sometimes cast, sometimes bored and turned from solid blocks of forged steel, so as to ensure sound metal throughout. Or a heavy forging is prepared, as in the Bris tol "Jupiter" radial engines, and the cylinder machined out of this, removing a large amount of metal. This appears in fig. 5, the outline of the forging being shown by thin lines. The forging weighs 86 lb., the finished piece only 18 lb.

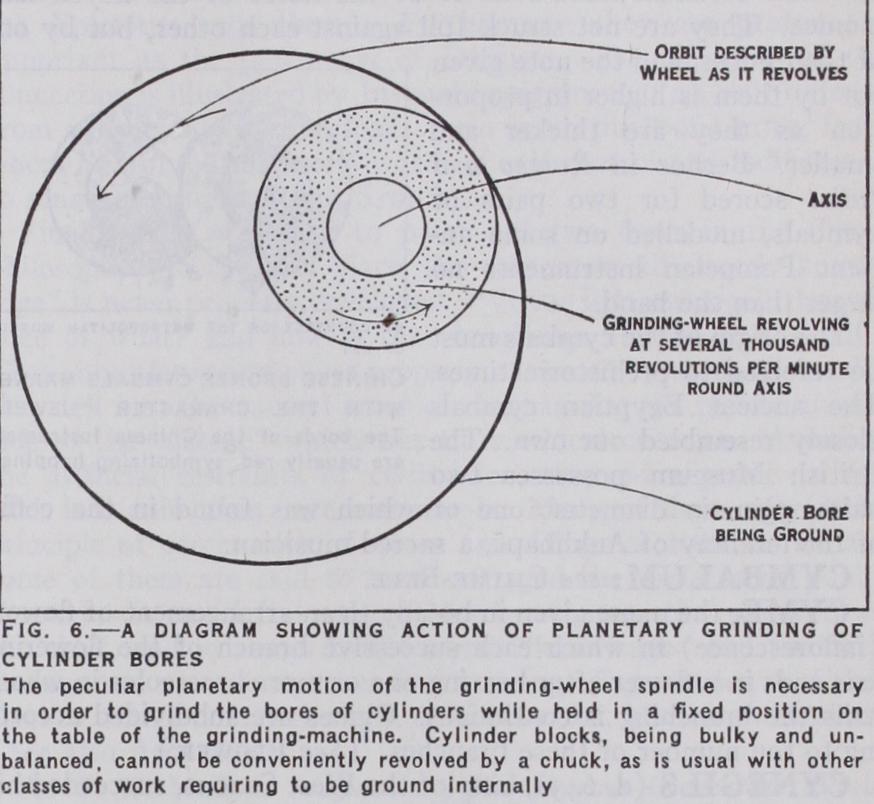

The importance of making a truly circular and parallel bore need scarcely be emphasized ; without this, wasteful leakages occur in any sort of cylinder, and the compression cannot be properly obtained in an internal-combustion engine. The methods of finish ing a bore from the casting or forging include boring, reaming, and grinding. The first-named process is often followed by the second to obtain superior finish and accuracy. Grinding gives a high mirror-finish, and by reason of the nature of the operation, which removes a mere film of metal, it tends to avoid distortion of the cylinder by pressure and heat. A number of machines have been developed for these operations, including single-spindle and multi spindle boring and reaming machines, for units and block castings. The grinding machines are specially designed for the purpose, having a planetary action to the wheel-spindle which can be moved round in a circle of lesser or greater diameter as required, while the spindle is turning on its own axis at 5,000 or 6,000 revolutions per minute (fig. 6). This peculiar action is necessary because the cylinders cannot be conveniently revolved, but must be clamped to a fixed table. Honing is a newer finishing process, a revolving and reciprocating spindle moving a circle of carborundum cylin ders round the bore and up and down. (See STEAM ENGINE; IN TERNAL COMBUSTION ENGINE; DIESEL ENGINE.) (F. H.).