Cyprus

CYPRUS, one of the largest islands in the Mediterranean, since 1914 a British Crown colony, at roughly equal distance from the coasts of Asia Minor to the north and of Syria to the east. The headland of Cape Kormakiti in Cyprus is distant 44 m. from Cape Anamur in Asia Minor, and its north-east point, Cape St. Andrea, is 69 m. from Latakieh in Syria. It lies between 33' and 35° 41' N., and between 32° 20' and 35' E. Its greatest length is about 141 m., from Cape Drepano in the west to Cape St. Andrea in the north-east, and its greatest breadth, from Cape Gata in the south to Cape Kormakiti in the north, reaches 6o m.; while it retains an average width of from 35 to 5o m. through the greater part of its extent, but narrows suddenly to less than 10 m. about 34° E., and from thence sends out a long narrow tongue of lard towards the E.N.E. for a distance of 46 m., termi nating in Cape St. Andrea. The coast-line measures 486 m., the area is 3,584 sq.m., or a little more than the area of Norfolk and Suffolk. Cyprus is the largest island in the Mediterranean after Sicily and Sardinia.

Mountains.

A great part of the island is occupied by two mountain ranges, both having a general direction from west to east. Of these, the most extensive and lofty fills almost the whole southern portion of the island, and is generally designated as Mt. Olympus. The highest summit, Mt. Troodos, attains 6,406 feet. Subordinate spurs diverge on all sides ; one extends to Cape Arnauti (the ancient Acamas), which forms the north-west ex tremity of the island ; others descend to the northern and southern coasts. South-east of the summit are governmental and military summer quarters. The main range is continued eastward by Mt. Adelphi (5,305 ft.), Papoutsa (5,124) and Machaira or Chionia (4,674), and ends in the isolated Hill of the Holy Cross (2,260 ft.), Santa Croce, Stavrovouni or Oros Stavro, a conspicuous object from Larnaca, only 12 m. distant , and a place of pil grimage. The northern range, a narrow but rugged and rocky ridge, begins at Cape Kormakiti (the ancient Crommyon) and is continued unbroken to the eastern Cape St. Andrea, a distance of more than loo miles. It has no collective name; its western part is the Kyrenia mountains, the remainder Carpas. Its highest summit (Buffavento) attains only 3,135 feet. It descends ab ruptly to the south into the great plain of Lefkosia, and to the north to a narrow plain bordering the coast.

The Mesaoria.

Between the two mountain ranges lies a broad plain, extending across the island from the bay of Famagusta to that of Morphou on the west, a distance of nearly 6o m., with a breadth varying from 10 to 20 miles. It is known by the name of the Mesaoria or Messaria. The chief streams are the Pedias and the Yalias, which follow roughly parallel courses eastward. The greater part consists of open, uncultivated downs; but corn is grown in the northern portions. Though Cyprus was celebrated in antiquity for its forests, the whole Mesaoria is now treeless. The disappearance of the forests (which is being artificially remedied) has reduct,l the rivers to mere torrents, dry in sum mer. Even the Pedias (ancient Pediaeus) does not reach the sea in summer, and forms unhealthy marshes. The mean annual tem perature in Cyprus is about 69° F (mean maximum 78° and minimum 57°). The mean annual rainfall is about 19 inches. October to March is the cool, wet season. Earthquakes are not uncommon.

Geology._Cyprus

lies in the continuation of the folded belt of the Anti-taurus. The northern coast range is formed by the oldest rocks in the island, consisting chiefly of limestones and marbles with occasional masses of igneous rock. These are sup posed to be of Cretaceous age, but no fossils have been found in them. On both sides the range is flanked by sandstones and shales (the Kythraean series), supposed to be of Upper Eocene age; and similar rocks occur around the southern mountain mass. The Oligocene consists of grey and white marls (known as the Idalian series), which are distributed all over the island and attain their greatest development on the south side of the Troodos. All these rocks have been folded, and take part in the formation of the mountains. The great igneous masses of Troodos, etc., con sisting of diabase, basalt and serpentine, are of later date. Plio cene and later beds cover the central plain and occur at intervals along the coast. The Pliocene is of marine origin, and rests un conformably upon all the older beds, including the Post-oligocene igneous rocks, thus proving that the final folding and the last volcanic outbursts were approximately of Miocene age. The caves of the Kyrenian range contain a Pleistocene mammalian fauna.

Population.

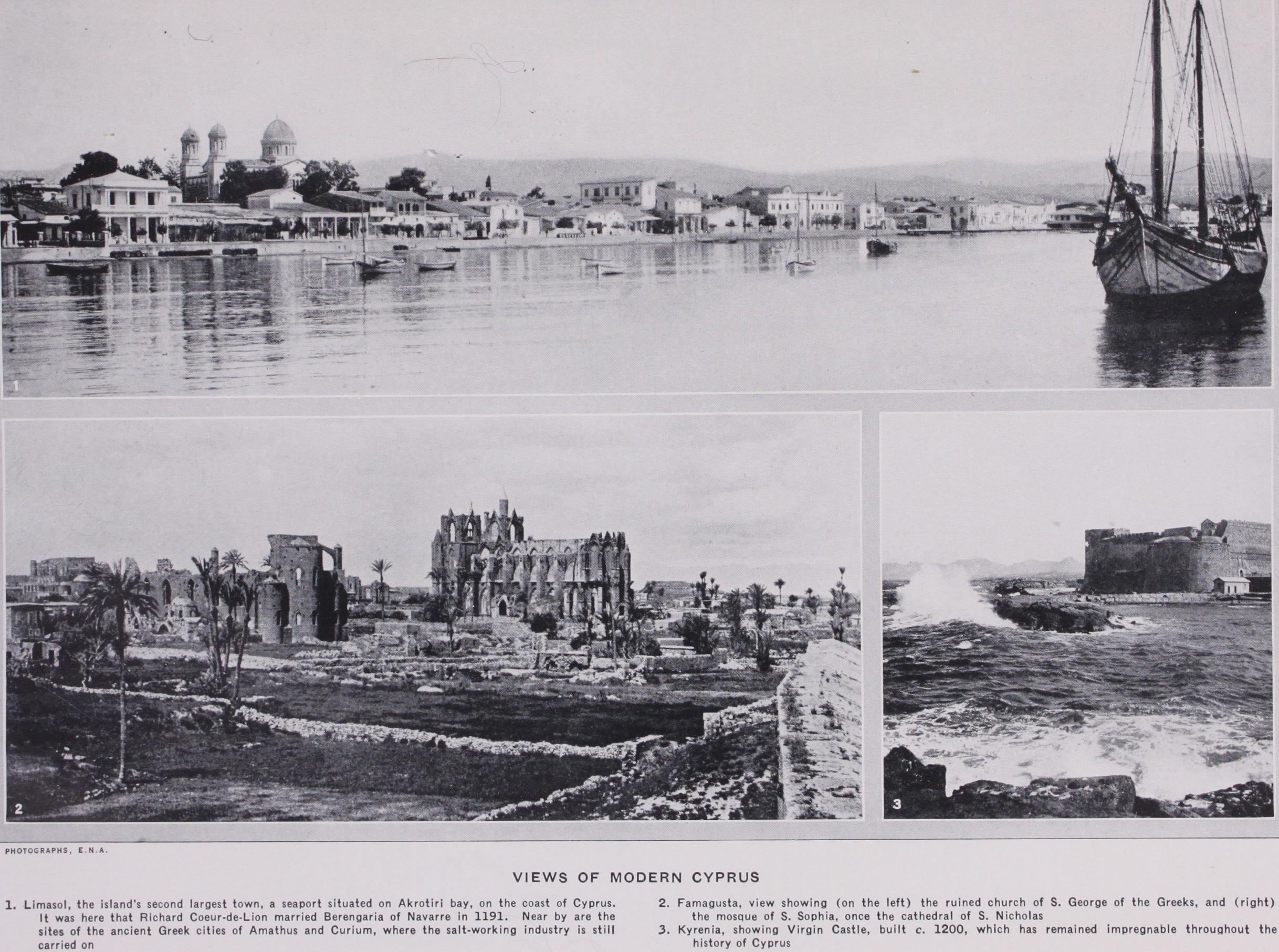

The population of Cyprus in 1931 was 347,959, of whom 61,422 were Mohammedans. The people are mainly Greeks and Turks. About 20% of the population are Muslims; nearly all the remainder are Christians of the Orthodox Greek Church. The Muslim religious courts, presided over by cadis, are strictly confined to jurisdiction in religious cases affecting the Mohammedan population. The island is divided into the six dis tricts of Famagusta, Kyrenia, Larnaca, Limasol, Nicosia and Papho. The chief towns are Nicosia (pop. 23,507), the capital, in the north central part of the island, Limasol (15,o66) and Lar naca (11,725) on the south-eastern coast. The other capitals of districts are Famagusta on the east coast, Kyrenia, a small port, on the north, and Ktima, capital of Papho, on the south-west.

Agriculture and Minerals.

The most important species of trees are the Aleppo pine, the Pinus laricio, cypress, cedar, carob, olive and Quercus alni f olia. Recent additions are the eucalyptus, casuarina, Pinus piney and ailanthus. Existing plantations are protected and extended under the Forestry Department. Agricul ture is the chief industry in the island. The soil is extremely fertile. A director of agriculture was appointed in 1896. The principal crops are grain, fruit, including carob, olive, mulberry, cotton, vegetables and oil seeds. Vineyards occupy a considerable area, and the native wines are pure and strong. Considerable works of irrigation have been undertaken since 1898, including a reser voir at Syncrasi (Famagusta), with a catchment of 27 sq.m. and a capacity of 70,000,000 cu.ft., and three large reservoirs in the Mesaoria to hold up the flood waters of the Pedias and Yalias rivers, and to irrigate 42,000 ac. (completed 1901), and, more recently, irrigation from artesian supplies in the Morphou district.The rearing of live stock, especially mules, is important. Arab stallions have been imported. Cattle, sheep, mules and donkeys are sent in large numbers to Egypt. The sponge fishery is im portant. Exports are embroideries, worked silk and cigarettes.

Arazi land is held by title deed issued by the Land Registry office; there are special categories of waste-land and trust-lands for public, religious or charitable purposes. illulk includes all buildings, gardens, planted land and grafted trees, and is in scribed at the Land Registry. All minerals belong to the State; permission is necessary for erection of buildings; and any land may be expropriated for public purposes. Most of the cultivated land is held by peasant proprietors. Of the total area, 3.584 sq.m., about 700 is State forest, 700 rocky waste, 400 reclaimable waste, 1,700 cultivated.

Cyprus was celebrated among the ancients for its mineral wealth, especially for its mines of copper. Some prospecting and mining has been done recently, but on a small scale. There are extensive salt works in the neighbourhood of Larnaca and Limasol. Asbestos is exported (10,904 tons in 1927). Gypsum is exported unburnt from the Carpas, and as plaster of Paris from Limasol and Larnaca. Statuary marble has been found on the slopes of Buffavento in the northern range.

Communications.

A disability working against the trade of Cyprus has been the want of natural harbours, the ports of Lar naca, Limasol and Papho possessing only open roadsteads ; though the construction of a satisfactory commercial harbour has been undertaken at Famagusta, and there is a small harbour at Kyrenia. In 1927, 5i8 steamships entered ports in Cyprus (tonnage 361) and 883 sailing vessels. Motor roads are being improved between the more important towns, and there is a light-railway from Famagusta to Nicosia and thence to Morphou. The Eastern Telegraph company maintains a cable from Alexandria (Egypt) to Larnaca, and the greater part of the lines on the island ; there is a weekly mail service via Egypt to London. (J. L. MY.) The governor has the assistance of an executive council and of a Legislative council on which a majority of elective members represent Muslim and Christian voters, in the proportion of 3 to 9. The administrative councils inherited from Turkish times retain restricted functions of assessment and land valuation. The six Turkish subdivisions have each a commissioner, administrative council, and courts of justice. Justice is administered according to the Ottoman code as amended by Cyprus statute law. There is a supreme court (with appeal in certain cases to the Privy Council) and in each district an assize court, a district court, a magistrate's court, and village courts as required. The higher courts have an English president, with Muslim and Christian assessors. The Cyprus military police includes both Christians and Muslims.

Finance and Trade.

The principal sources of revenue are from customs, port and other dues on shipping; tithe on grain and caroubs; export duties on other crops and produce, and taxes on live-stock, on land and buildings; excise; licences, etc., and the salt monopoly. Revenue has risen from £176,000 in 1878 to about in 1928. Currency is based on the gold sovereign divided into 180 "copper piastres"; silver and copper coins are struck for local use. The Imperial Ottoman Bank and the Bank of Athens have agencies in the principal towns : there are also Government savings banks and an agricultural bank.The chief exports (f1,585,940 in 1927) are caroubs, cattle (especially mules), barley, wine and spirit, raisins and other fruits, cotton, silk and wool; chief imports (£1,542,87o in 1927) are flour, sugar, cotton and woollen goods, coffee, leather, soap, petroleum, timber, machinery and hardware. Trade with the United Kingdom is represented by 44.65% of the imports, and 18% of the exports. Turkish weights and measures are used.

Education.

The Turks expended f goo annually on certain Muslim schools; others had endowments; Christian schools were maintained by subscriptions. In 1881 a system of grants in aid of local contributions began, administered by boards of Muslim and Christian Education through district and village committees, with separate provision for Armenian and Maronite schools. At Nicosia there are separate secondary schools for Muslim and Christian boys and girls. An English school on grammar school lines receives pupils of all races and creeds, and attracts pupils from neighbouring countries. The endowed Mitzis-Lemythou school is commercial; the Presbyterian Mission school at Larnaca prepares for the American college at Beirut. Prisoners are in structed in handicrafts, and there is a farm-hospital, leper. (X.) The Stone age has left but few traces in Cyprus. The "mega lithic" monument of Hala Sultan Teke near Larnaca may perhaps be early, but the vaulted chamber of Agia Katrina near Enkomi is Roman, and the chapel of Agia Phareromeni at Larnaca is a tomb of similar late date. The perforated monoliths at Ktima seem to belong to oil presses of uncertain date. A neolithic settlement is reported at Frenaros.The Bronze age, on the other band, is of peculiar importance since Cyprus was one of the chief early sources of copper. Throughout this period, which began probably before 300o B.C. and ended about 1200 B.C., Cyprus evidently maintained a large population, and distinct art and culture. This culture falls into three main stages. In the first, the implements are of copper, the pottery is hand-made, with a red burnished surface, gourd-like forms and incised patterns ; zoomorphic art is rare, and imported objects are unknown. In the second stage, implements of bronze (9 to io% tin) became common; pottery of buff clay with painted geometrical patterns appears alongside the red-ware; and foreign imports occur, such as Egyptian blue-glazed beads.

In the third stage, Aegean colonists introduced the Mycenaean culture and industries; with new types of weapons, wheel-made pottery, a naturalistic art which rapidly becomes conventional; gold, ivory, glass and enamels. Intercourse with Syria, Palestine and Egypt brought other types of pottery, jewellery, etc. There is, however, nothing in this period which can be ascribed to specifically "Phoenician" influence; the only traces of writing are in a variety of the Aegean script (British Museum, Excavations in Cyprus, 1900). It is in this third stage that Cyprus first appears in history, under the name Asi, as a conquest of Tethmosis (Thothmes) III. of Egypt (18th dynasty, c. B.c.) (E. Ober hummer, Die Insel Cypern, Munich, 1903, i., pp. 1-3). It was still in Egyptian hands under Seti I., and Rameses III. Alasya, sometimes identified with Cyprus, is probably in north Syria.

The Early Iron age which succeeds is a period of obscurity and relapse. The introduction of iron was accompanied, as in the Aegean, by economic and political changes, which broke up the Mycenaean colonies. Foreign imports almost cease ; cylinders and scarabs are replaced by conical seals like those of Asia Minor, and dress-pins by brooches (fibulae). Representative art languishes; decorative art becomes purely geometrical. Lingering thus, Mycenaean traditions met new oriental influences from the Syrian coast. But there is no clear proof of Phoenician or other Semitic activity in Cyprus till the end of the 8th century.

No reference to Cyprus has been found in Babylonian or Assyrian records before the reign of Sargon II. (end of 8th century B.e.). The Hebrew geographers of this and the next century reckoned it as predominantly Greek. Sargon's campaigns in north Syria, Cilicia and south-east Asia Minor (721-711) provoked first attacks, then an embassy and submission in 709, from seven kings of Yatnana (the Assyrian name for Cyprus) ; and an inscription of Sargon himself, found at Citium, proves an Assyrian protectorate. Under Sennacherib's rule, Yatnana figures (as in Isaiah) as the refuge of a disloyal Sidonian in 702 ; but in 668 ten kings of Cypriote cities joined Assur-bani-pal's expedition to Egypt. Citium does not appear by name ; but is recognized in the list under its Phoenician title Karti-hadasti, "new town." Thus before the middle of the 7th century Cyprus reappears in history divided among at least ten cities, of which some are certainly Greek, and one at least certainly Phoenician. With this, Greek tradition agrees'. The settlements at Paphos and Salamis, and probably at Curium, were believed to date from the period of the Trojan War. Late Mycenaean settlements were discovered on these sites. The Greek dialect of Cyprus shows marked re semblances to that of Arcadia from which it must have been separated not later than the 1 2th century. Further evidence of continuity is the peculiar Cypriote script, a syllabary related to the linear scripts of Crete and the south Aegean, and traceable in Cyprus to the Mycenaean It remained in regular use for Greek records until the 4th century at least ; before that time the Greek alphabet occurs in Cyprus only in a few inscriptions erected for A few inscriptions in the syllabary preserve another language which has not yet been identified. In Citium and Idalium, a Phoenician dialect and alphabet were in use from the time of Sargon onward'. Sargon's inscription at Citium is The culture and art of Cyprus in this Graeco-Phoenician period are well represented, the earlier phases at Lapathus, Soli, Paphos and Citium; the later Hellenization at Amathus and Marion Arsinoe. Three distinct foreign influences may be distinguished, originating in Egypt, in Assyria and in the Aegean. Their effects are best seen in sculpture and in metal work, though it remains doubtful whether the best examples of the latter were made in Cyprus or on the mainland'. The first two merged in a mixed art which, from its intermediate position between the art of Phoenicia and its western colonies and the earliest Hellenic art in the Aegean, has been called Graeco-Phoenician. Pottery-painting for the most part remains geometrical. Those Aegean influences, however, which had predominated in the later Bronze age, and had never wholly ceased, revived, as Hellenism matured and spread, and slowly repelled the mixed Phoenician orientalism. Early in the 6th century appear the specific influences of Ionia and of Naucratis. The revival of Egypt as a phil-Hellene state under the 26th dynasty, admitted strong Graeco-Egyptian in fluences in industry and art, and led, about 56o B.C., to the con quest of Cyprus by Amasis (Ahmosi )II.' The annexation of Egypt by Cambyses of Persia in 525 B.c. was preceded by the voluntary surrender of Cyprus, which formed part of Darius's "fifth satrapy."' The Greek cities joined the Ionic revolt in 50o but the Phoenician States, Citium and Amathus, remained loyal to Persia ; the rising was soon put down; in 48o Cyprus furnished 150 ships to the fleet of ; and remained subject to Persia during the 5th century'. But the Greek cities retained monarchical government throughout, and domestic arts and religious cults remained almost unaltered. The prin cipal Greek cities were now Salamis, Curium, Paphos, Marion, Soli, Kyrenia and Chytri. Phoenicians held Citium and Amathus on the south coast, Tamassus and Idalium in the interior. At the end of the 5th century a fresh Salaminian League was formed by Evagoras (q.v.), who became king in 410, aided by the Athenian Conon after the fall of Athens in 404, and revolted openly from Persia in 386, after the peace of Antalcidas. Athens again sent help. But the Phoenician states supported Persia as before, the Greeks were divided by feuds, and in 38o the attempt failed ; Evagoras was assassinated in 374, and his son Nicocles died soon after. After the victory of Alexander at Issus in 333 all the states of Cyprus welcomed him.

After Alexander's death in 323 Cyprus passed, after several rapid changes, to Ptolemy I., king of Egypt. In 306 B.C. Deme trius Poliorcetes of Macedon overran the whole island, but Ptolemy recovered it in 295 B.c. Under Ptolemaic rule Cyprus was usually governed by a viceroy of the royal line, but it gained a brief independence under Ptolemy Lathyrus (107-89 B.c.), and under a brother of Pto'emy Auletes in 58 B.C. The great sanc tuaries of Paphos and Idalium, and the public buildings of Salamis, which were wholly remodelled in this period, have produced but few works of art. It is in this period that we first hear of Jewish settlements' which later become populous.

In 58 B.c. Rome, which had made large unsecured loans to Ptolemy Auletes, sent M. Porcius Cato to annex the island. Under Rome, Cyprus was at first appended to the province of Cilicia; after Actium (31 B.c.) it became a separate province, which remained in the hands of Augustus and was governed by a legatus Caesaris pro praetore as long as danger was feared from the East. No monuments remain of this period. In 22 B.C., however, it was transferred to the senate', so that Sergius Paulus, who was governor in A.D. 46, is rightly called Of Paulus no coins are known, but an inscription Other pro consuls are Julius Cordus and L. Annius Bassus who succeeded him in A.D. The persecution of Christians on the mainland after the death of Stephen drove converts as far as Cyprus ; and soon of ter converted Cypriote Jews such as Joses the Levite (better known as Barnabas), were preaching in Antioch. The latter revisited Cyprus twice, first with Paul on his "first jour ney" in A.D. 46 and later with Mark'. In 116-117 the Jews of Cyprus, with those of Egypt and Cyrene, revolted, massacred 240,00o persons, and destroyed a large part of Salamis. Hadrian, afterwards emperor, suppressed them, and expelled all Jews from Cyprus.

For the culture of the Roman period there is abundant evi dence from Salamis and Paphos, and from tombs everywhere, for the glass vessels which almost wholly supersede pottery in tombs are much sought for their (quite accidental) iridescence.

The Christian Church of Cyprus was divided into 13 bishoprics. It was made autonomous in the 5th century, in recognition of the supposed discovery of the original of St. Matthew's Gospel in a "tomb of Barnabas," still shown at Salamis; and the patriarch has the right to sign his name in red ink. A council of Cyprus, summoned by Theophilus of Alexandria in A.D. 401, prohibited the reading of the works of Origen (see CYPRUS, CHURCH oF).

Of the Byzantine period little remains but the ruins of the castles of St. Hilarion, Buffavento and Kantara; and a series of 'gold ornaments and silver plate, found at Lapithus in 1883 and 1897 respectively. The Frank conquest is represented by the "Crusaders' Tower" at Kolossi, and the church of St. Nicholas at Nicosia; and, later, by masterpieces of a French Gothic style, such as the church (mosque) of St. Sophia, and other churches at Nicosia; the cathedral (mosque) and others at Famagusta (q.v.), and the monastery at Bella Pais; as well as by domestic architecture at Nicosia ; and by forts at Kyrenia, Limasol, etc.

History of Excavation.

Practically all the archaeological discoveries above detailed have been made since 1877. T. B. Sandwith, British consul 1865-69, laid the foundations of a sound knowledge of Cypriote ; his successor, R. H. Lang (1870-72), excavated a sanctuary of Aphrodite at and Gen. Louis P. di Cesnola (q.v.), American consul, explored sites and tombs in all parts of the island, from 1865 to 1877. His col lection, now in the Metropolitan museum of New York, remains the largest series of Cypriote antiquities in the world.At the British occupation in 1878, the Ottoman law of in regard to antiquities was retained in force. Excavation was permitted under Government supervision, and the finds were apportioned in thirds, between the excavator, the landowner (usually bought out by the former), and the Government. The Government thirds lay neglected in a "Cyprus museum" main tained at Nicosia by voluntary subscription until it was organized as a Jubilee Memorial in 1897. A catalogue of these collections was published in 1899'. After 1878 more than 70 distinct ex cavations were made, of which the most important were con ducted by Dr. Ohnefalsch Richter for private individuals and German institutions, at Idalium and Tamassus; by the Cyprus Exploration Fund at Paphos, Marion and Salamis, and by the British Museum at Amathus, Salamis and Curium. But in 1905 a new Antiquity Law imposed restrictions which.in effect stopped scientific excavation by foreigners. Only in 1927 were these restrictions somewhat relaxed and a Swedish mission has begun work at Soli. (J. L. MY.) After the division of the Roman empire (A.D. 395) Cyprus passed into the hands of the Eastern emperors, to whom it con tinued subject, with brief intervals, for more than seven centuries. It was administered as a pro-consulship by an official appointed from Antioch, the capital being transferred from Paphos to 'Corp. Inscr. Lat. 263 r-2632.

iv. 36, xi. 19

, 20, xiii. 4-13, xv. 39, xxi. 16.xlv. (1877), pp. 127, 142.

Roy. Soc. Literature, end ser. xi. (1878), pp. 3o sqq.

and Ohnefalsch-Richter

, A Catalogue of the Cyprus Museum, with a Chronicle of Excavations since the British Occupation, and Introductory Notes on Cypriote Archaeology (Oxford, 1899).Salamis (then known as Constantia). Until 632 the island was exceedingly prosperous, but in that year began the period of Arab invasions, which continued intermittently for three centuries. In 647 the Arabs under the caliph Othman made themselves masters of the island, and destroyed Salamis, but were driven out by the emperor only two years later. Again conquered by the Arabs in the reign of Harun al-Rashid (802), Cyprus was finally restored to the Byzantine empire under Nicephorus Phocas (963-969). Its princes became practically independent, and tyrannized the island, until, in I191, Isaac Commenus, who in 1184 had assumed the title of Despot of Cyprus, provoked the wrath of Richard I., king of England, by wantonly ill-treating his crusaders. Richard there upon wrested the island from Isaac, whom he took captive. He then sold Cyprus to the Knights Templars, who resold it to Guy de Lusignan, titular king of Jerusalem.

Guy ruled from 1192 till his death in 1194 ; his brother Amaury took the title of king, and from this time Cyprus was governed for nearly three centuries by a succession of kings of the same dynasty, who introduced into the island the feudal system and other institutions of western Europe. Their court was a brilliant one, and the kings of Cyprus in addition often bore the title of kings of Jerusalem, and after 1393, of Armenia also. In 1372, indeed, following a quarrel between the Venetian and Genoese consuls, the Genoese took Famagusta, which had become the chief commercial city in Cyprus, and held it till 1464; but it was recov ered by King James II., and the whole island was reunited under his rule. His marriage with Caterina Cornaro, a Venetian lady of rank, was designed to secure the support of the powerful republic of Venice, but had the effect, after his own death and that of his son James III., of transferring the sovereignty of the island to his new allies. Caterina, feeling herself unable to con tend alone with the increasing power of the Turks, abdicated the sovereign power in favour of the Venetian republic, which at once entered into full possession of the island (1489)• The Venetians retained their acquisition for 82 years, notwith standing the neighbourhood of the Turks. Cyprus was now harshly governed by a lieutenant, and the condition of the natives, who had been much oppressed under the Lusignan dynasty, became worse. In 1570 the Turks, under Selim II., made a serious attempt to conquer the island, in which they landed an army of 6o,000 men. The greater part of the island was reduced with little difficulty; Nicosia, the capital, was taken after a siege of 45 days, and 20,000 of its inhabitants put to the sword. Famagusta alone made a gallant and protracted resistance, and only capitu lated after a siege of nearly a year (Aug. 6, 15 71) . The terms of the capitulation were shamefully violated by the Turks, who j put to death the governor Marcantonio Bragadino with cruel tor ments.

On March 7, 1573, Venice recognized the Sultan's sovereignty over Cyprus. The period of Turkish administration lasted for 200 years. At first comparatively mild (serfdom was abolished, the Orthodox archbishopric restored, and the Christian popula tion granted a large measure of autonomy), it became increasingly oppressive. There were serious risings in 1764, 1804 and 1821. In 1838 and 1839 attempts were made to introduce reforms and some self-government, with a local Divan. On June 4, 1878, Great Britain, by treaty with the sultan, took over the occupation and administration of Cyprus, the Porte remained nominal sovereigns, and received an annual "tribute" of £92,80o a year.

Annexation by Great Britain.

On the outbreak of war with Turkey on Nov. 5, 1914, Cyprus was formally annexed to the British Crown and became an integral part of the British Empire. In the proclamation then issued, it was announced that every Ottoman subject residing in the island would become a British subject unless he notified in writing within a stated period his desire to retain his Ottoman nationality. With the exception of a few non-Cypriote Turks temporarily residing in the island, all accepted British nationality, the Greek-speaking inhabitants with enthusiasm and their Turkish-speaking compatriots without demur. The change of status of the island was effected quietly and with out incident of any kind, and involved no material alteration in administration. The so-called "Turkish tribute" continued to be borne by the revenue, being termed the "Cyprus share of the Turkish debt charge." The annexation was recognized by Turkey in the Treaty of Lausanne, 1923. Following the Cyprus (legislative council) order in council of Feb. 6, 1925, the island was formally elevated to the status of a colony on May 1, 1925; the high commissioner was to be known after that date as the Governor. In the legislative council the non-Moslem representation was increased to 12, the council thus consisting of nine official and 15 elected members. The Greek-speaking Cypriotes for many years clamoured for Cyprus to be united to Greece, which they consider as their mother country; but Greece has not shown any great desire to encourage the agitation, and the British Government does not recognize the claim as well founded.The island's finances were placed on a sound basis in 191 r by fixing an annual grant-in-aid of £50,00o from the Imperial Govern ment in substitution for the unsatisfactory arrangement previously in force, whereby the Imperial Government had year by year made good any deficit that might occur between revenue and expenditure.