Cytology

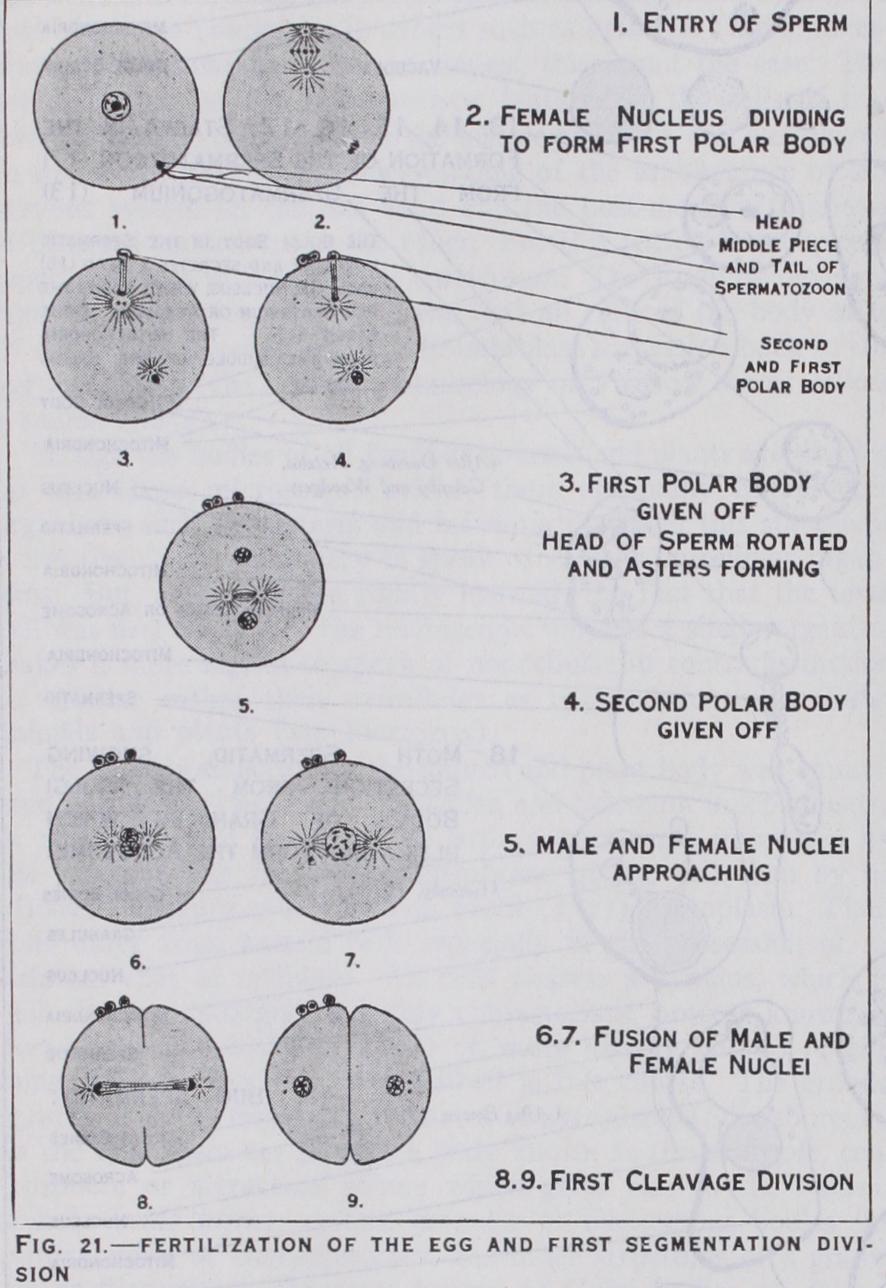

CYTOLOGY is the term applied to the study of those micro scopic units of the bodies of animals and plants, known as cells. To obtain a clear idea of the nature of cells a brief consideration of the fundamental character of the reproductive processes of animals and plants will greatly assist. This knowledge is, compar atively speaking, of recent growth. It was long after the time of Linnaeus, who first generalized the principle that like begets like, that the universal similarity of the reproductive processes was first clearly appreciated. The reader is presumably familiar with the fact that some herrings have hard roes and others soft roes. Suppose that a number of live herrings are taken at the period of spawning, and the roes removed and placed separately in bowls of sea water. On teasing up the hard roes a suspension of spherical bodies is obtained. These objects when shed into the sea normally give rise to offspring, and are therefore called eggs, or ova. A suspension of soft roe, though displaying no constituents of visible size, is seen under the microscope to swarm with minute objects, moving about like tadpoles with lashing movements of a whip like filament or tail. These motile units, known as spermatozoa, or, shortly, sperms, were first observed in the seminal fluid of man by Leeuwenhoek (1677). Left to itself the suspension of eggs will not display any immediate change : they will not develop into herring larvae. But if a drop of the sperm suspension is added, changes are initiated that betoken the development of a new or ganism from each egg. Towards the end of the century the Abbot Spallanzani author of many ingenious experiments outside the field of divinity, showed that, when a fluid contain ing sperm is filtered, the filtrate has no fertilizing power. Evi dently, therefore, the initiation of development or fertilization involves the access of the sperm to the egg. It was not until that Hertwig and Fol independently observed beneath the micro scope the entry of the sperm into the egg of the sea urchin, and showed that only one sperm normally fertilizes one egg. Subse quent research has vindicated the truth of this conclusion for all animals, and has shown that an essentially similar union underlies the sexual process in plants. Soon after the penetration of the sperm into the egg, the latter is seen to undergo a process of seg mentation, indicating that development has begun. The separate segments are known as cells (q.v.).

The term cell had been used long before the discovery of fertil ization, as will be indicated later on. But as the early development of cytology has been closely linked with the study of inheritance, it will be well to concentrate at first on the character of the sexual process. Those structures which in animals produce sperm, like the soft roe of the herring, are collectively called testes. Those which produce ova are known as ovaries. An animal which pos sesses testes is called a male, and an animal which possesses ovaries a female. A number of animals, e.g., earthworms and snails, possess both and are referred to as hermaphrodite. In some species the slimy secretion or seminal fluid containing the sperm is shed into the water : in others it is introduced into the reproduc tive passages of the female. But from a jelly fish to an insect and from an insect to man himself, whether in bisexual or hermaphro dite animals, the essential event which precedes the development of a new being is the union of a single sperm with a single egg.

Spermatozoa and ova are sometimes referred to as germ cells or gametes. The sperm is always a microscopic entity and in nearly all animals its appearance is very much the same : it con sists of a small body and a long vibratile filament or flagellum (absent in the sperm of lobsters and threadworms). Ova of dif ferent animals on the contrary are of very different dimensions in accordance with the extent of provision (yolk, etc.) made for the development of the new organism before it commences a free liv ing existence. Sometimes it is invested with a protective envelope (shell) secreted by the walls of the female ducts. But in all cases the immature egg of animals is essentially like the segments into which it divides after fertilization. It is a spherical or ellipsoidal body in which a clear spherical vesicle, the nucleus, is seen in the living condition. This nucleus after a suitable method of killing (fixation) readily absorbs basic dyes. The cells or segments into which the fertilized egg divides also contain a similar structure, and the division of the nucleus is an essential feature in segmenta tion or cell division. When the testis is examined microscopically it is found, as first shown by Kolliker in 1841, that each sperm is developed from a single element similar to the immature egg. Thus the structure of the testis and ovary is made up of micro scopic bricks or cells, many of which are seen to be in process of dividing into two, so that new germ cells are constantly in process of manufacture.

Like the testis and the ovary the bodies of animals and plants as a whole are built up of the microscopic bricks which have been termed cells. All cells have certain characteristics in common such as the possession of the structure referred to as the nucleus. These will be enumerated later. But as development proceeds the cells of the segmenting egg begin to assume special characteristics, so that different types of tissues are differentiated. In some tissues like bone and cartilage the bricks or cells are separated by a good deal of plaster (matrix). In others such as epithelia (lining mem branes), muscular and nervous tissues, this is not the case. The detailed study of the characteristic features of the cells of dif ferent tissues is treated under the histology (q.v.), and has played an important part in an understanding of the architecture of the nervous system on the one hand and the post-mortem diagnosis of diseased conditions on the other. For this reason it occupies a separate status in the medical curriculum. The study of develop ment or embryology (q.v.) shows that all cells of the body arise by division of pre-existing cells in unbroken succession back to the egg itself, or in the historic phraseology of Virchow omnis cellula e cellula Though the bodies of all familiar animals and plants are divided up into these microscopic bricks, there are many microscopic organisms such as bacteria and infusoria of which this statement is not true. It is customary to speak of such as unicellular organ isms. But, as Dobell has rightly insisted, the fact that the term cell was first applied to the microscopic units of a single organism makes it more logical to speak of noncellular in contradistinction to cellular rather than unicellular as opposed to multicellular animals and plants (see PROTOZOA).

The cellular structure of the animal and plant body was enunci ated as a general notion by Schleiden and Schwann independently in 1839, but, like Hooke, these writers were more impressed by the external wall or limiting membrane of the cell than by its viscous substance called by Von Mohl (1847) protoplasm. Plant cells differ from animal cells especially in the possession of an external coat of cellulose. All cells possess a nucleus, which in cell division undergoes a highly characteristic process known as karyokinesis (Schleichen, 1878) or, more usually mitosis (Flem ming, 1882) . This will be described in due course. The ground substance of the remainder is known as cytoplasm (Strassburger). In the cytoplasm are present a body known as the centriole, cen trosphere or attraction sphere which gives rise to the nuclear spindle (vide infra), certain granular or filamentous bodies the mitochondria or chondriosomes, and other structures of a granu lar or filamentous character known as Golgi bodies or dictyo somes, the last two being referred to as cytoplasmic inclusions (q.v.). The behaviour of these latter in the process of the matu ration of the germ cells, fertilization and development does not throw any light on the understanding of inheritance. But the history of the nucleus has features which are of the utmost im portance in this connection. Indeed the correspondence between microscopic observations on the nuclear constitution in the germ cell cycle of animals and plants and the hypothetical material units inferred from breeding experiments constitutes one of the most spectacular developments in modern biology. Since these facts can be elicited from preserved and stained material more easily than from living cells, the significant developments in descriptive cytology may best be considered in reference to the interpreta tion of hereditary transmission.

Behaviour of the Nucleus.

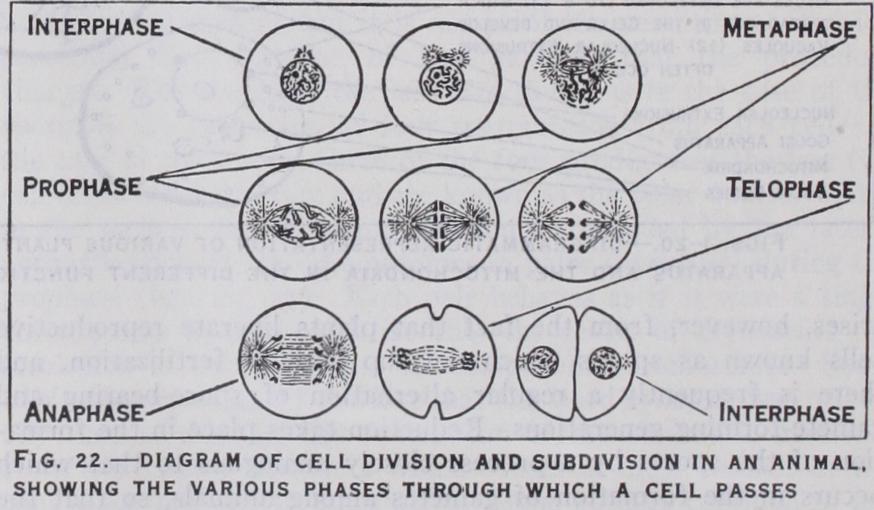

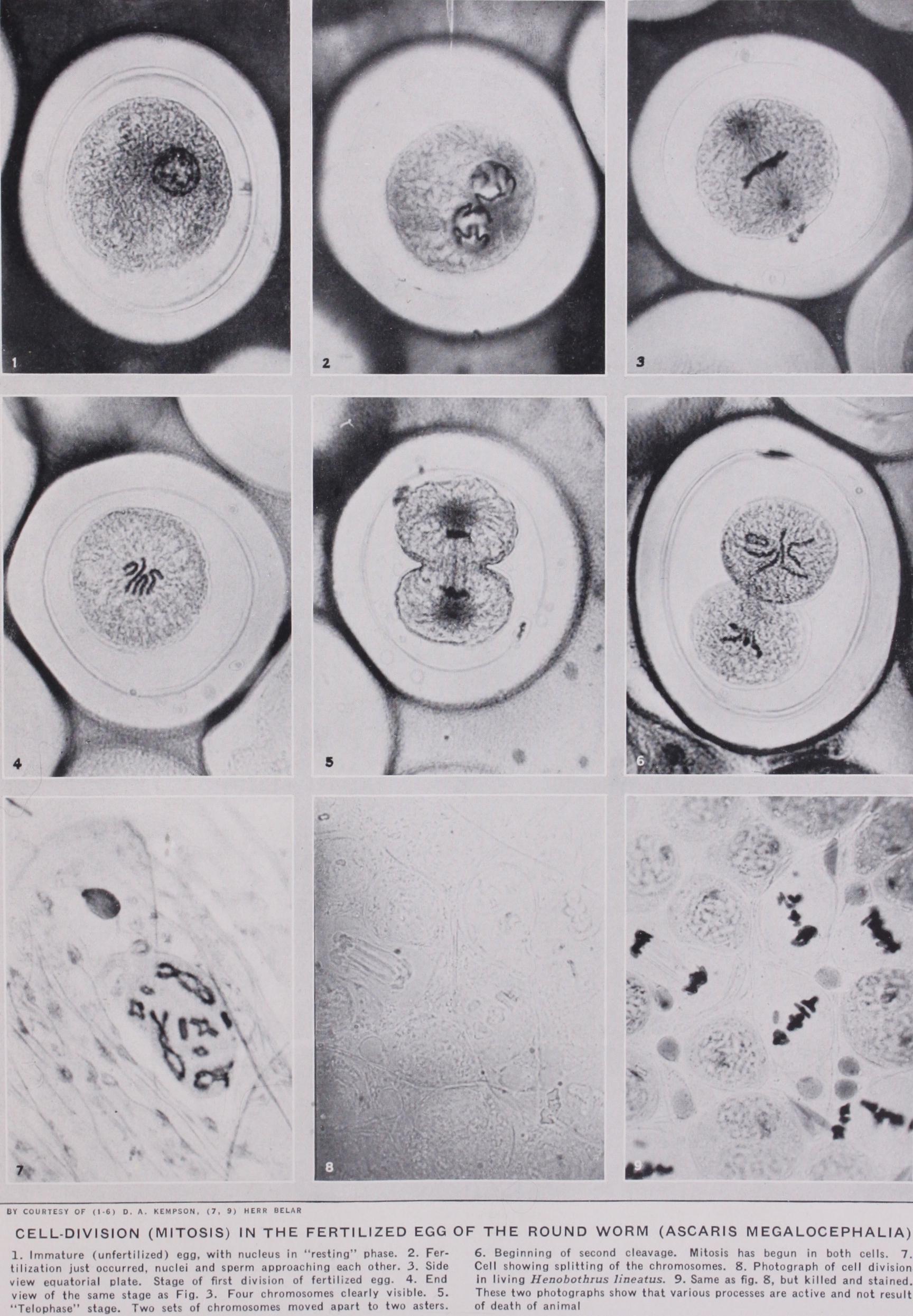

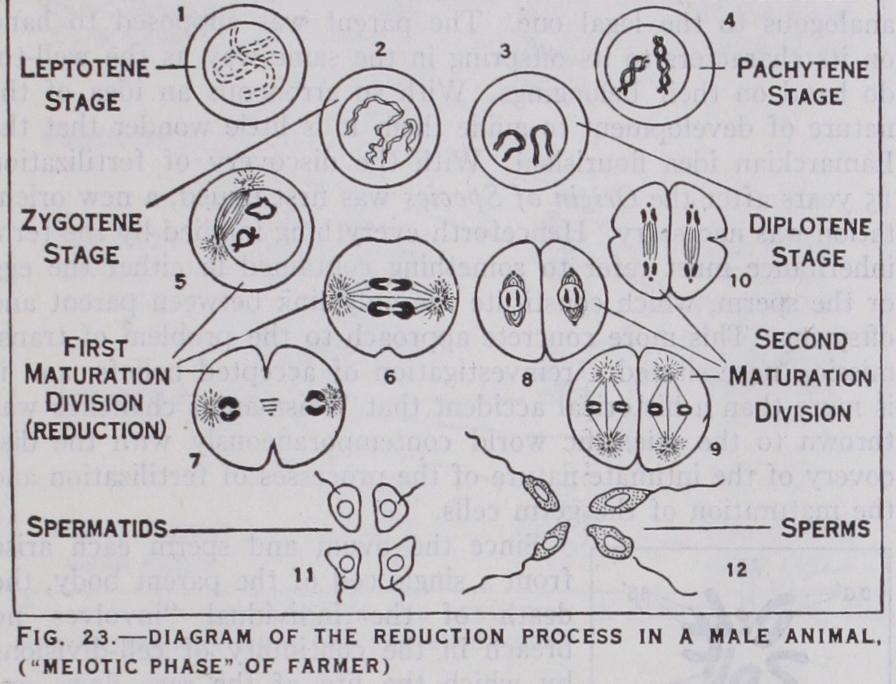

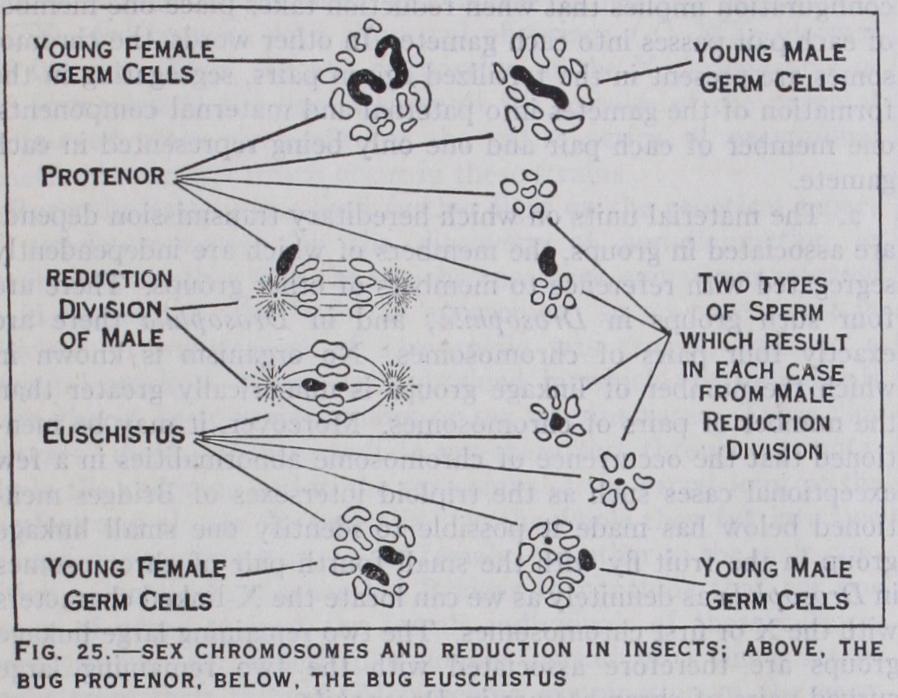

The nucleus of a resting cell appears in microscopic preparations as a vesicle containing a tangle of fine threads. At one side of the nucleus is a small struc ture, the attraction sphere, whose separation into two parts heralds the inception of cell division. As the two attraction spheres separate they appear to draw out the intervening cytoplasm into a spindle of fine fibrils. Meanwhile changes have occurred within the nucleus. The tangle of fine threads has resolved itself into a number of readily distinguishable filaments which become progress ively shorter, assuming the appearance of stout blocks of material, staining deeply with basic dyes, and hence called chromosomes. The limiting outline of the nucleus now becomes unrecognizable, the chromosomes arrange themselves at the equator of the spindle and split into longitudinal halves. Each half passes to the opposite end of the spindle and, while the constriction of the cytoplasm occurs, the daughter chromosomes spin out again into finely spun thread or become more and more vesicular, fusing eventually to form the resting nucleus. Thus each of the chromosomes of any cell appears to be structurally related to a corresponding chromo some in that of the preceding and succeeding generation, a conclu sion first explicitly stated by Rabl in 1885. The whole process, now known as mitosis, was not elucidated until the '7os. Various terms are used to denote different stages in nuclear division : these are interphase (spirophase of Bolles Lee) or resting nucleus, prophase, when the chromosomes first become distinct in prepara tion for division, metaphase, when they lie on the equator of the spindle, anaphase, when they travel towards the opposite ends, and telophase, as they pass into the resting condition again. It must be borne in mind, however, that the whole process is continuous, and can be recorded cinematographically in the living condition.In every species of organism the number of chromosomes is constant in all the cell divisions of the segmenting egg or young gonads. Thus in man the number is 48 ; in the fruit fly it is eight ; in the Indian runner duck it is about 7o; in the lily it is 24, as also in the salamander, the royal fern and the hellebore. If Rabl's doctrine is correct some arrangement must exist to provide for the fact that at fertilization the union of the male and female germ nuclei involves the equal contribution of both to the chromo some constitution of the new being; otherwise the number would be doubled at each generation. Such provision does. exist, hence the restriction implied in the reference to young gonads above. It is found that the nuclei of the germ cells continue to divide in the manner described consistently, until the last division but one pre ceding the formation of the cell which becomes the sperm or is the ripe egg. As far as the nuclei are concerned the process is the same in both sexes. The constancy of the chromosome numbers of different species of animals and plants was discovered during the '7os by the work of Flemming, Strassburger, Butschli and other investigators, and this discovery immediately gave rise to the problem just stated, viz., how this constancy is maintained from generation to generation. A few years later, working on the fertilization of the horse threadworm (Ascaris), a species with only four chromosomes in its segmenting nuclei, two investigators, Van Beneden (1881) and Boveri (1883) showed that the egg and the sperm each contribute half the number of chromosomes char acteristic of normal cell divisions to the fertilization nucleus, and that the last division but one preceding the formation of the ripe egg or sperm in the gonad involves reduction of the chromosome number. Innumerable cell divisions of the ordinary type occur in the young gonads, but it is not until the penultimate division preceding the formation of ripe gametes that the procedure changes. The result of the last two divisions in the case of the sperm is the formation of four spermatozoa from each cell. In the case of the female three of the four products of the last two cell divisions degenerate and are known as the polar bodies. With in the nucleus the reduction division is preceded by the lateral approximation of the chromosomes in pairs (synapsis) during the prophase (figs. 22, 23). Each pair behaves as if it were a single chromosome in metaphase, so that the result of division is the resolution of each pair into its component chromosomes. Some confusion arises out of the fact that the word synapsis was origin ally used to describe the contraction of the chromatic filaments from the nuclear periphery which occurs in most animals at the time when the pairing takes place. Some authors continue to use the term in this sense. Others have adopted at Hucker's sugges tion the terms syndesis to signify the pairing, and synizesis to imply the contraction. The succeeding division is typical, i.e., each chromosome divides lengthwise, though, of course, the total num ber of chromosomes that divide on the spindle of the last division is half the normal number in consequence of the character of the preceding division. As stated earlier essentially similar phenomena underlie the reproductive processes of plants and, with the excep tion of flowering plants and most fungi, the gametes (spermato zoids) and egg cells have characteristics similar to the correspond ing elements in animals, the sperm being motile. A complication arises, however, from the fact that plants liberate reproductive cells known as spores which develop without fertilization, and there is frequently a regular alternation of spore-bearing and gamete-forming generations. Reduction takes place in the forma tion of the spores by a process closely analogous to that which occurs in the formation of gametes among animals, so that the sexual generation has half the number of chromosomes in its dividing cells as are present in dividing cells of the sporophyte. In flowering plants this alternation is truncated by the extreme reduction of the gamete-bearing generation. Reduction precedes the formation of the spores, which are of two kinds, pollen cells and the "embryo sacs" contained within the ovules. Within the pollen cells two immotile male gametes are typically formed, and within each embryo sac several cells, one of which behaves as an egg cell, are formed. When the pollen is transferred to the pistil, one of the male gametes is brought into contact, by the formation of a pollen tube, with the egg cell within the ovule, and their nuclei unite. By division of the fertilized egg cell an embryo plant is formed within the covering membranes of the ovule. The embryo together with its parental envelopes is known as the seed (q.v.) .

At fertilization the normal number of chromosomes is restored by the union of the nuclei of egg and sperm, so that each ordinary cell of the organism has a set of chromosomes half of which are of maternal and half of paternal origin. Now in many animals and plants it is possible to distinguish among the chromosomes pairs of different sizes and shapes. Not only is there a constancy of number of chromosomes in a given species, but in addition a con stancy in the configuration of the chromosomes. It is thus possible to see that reduction involves something more than the mere halv ing of the number of chromosomes, that is to say, a definite sorting out by which each gamete receives one representative of each pair. Only by such a process could the constancy of shape of dif f erent pairs be preserved. This fact is of such far-reaching theo retical significance that a concrete instance may be taken to make it more clear to the reader. In the unripe germ cells of the testis of the stone fly Perla (Nakahara, 1919) the chromosome complex (fig. 24) of dividing nuclei consists of ten elements differing inter se in the following way : one pair a, a' are rod-like and equal, two pairs '0,73 and y,y are V-shaped, one pair are much smaller and spherical, 3, 3', and a pair of unequal rods referred to as X and Y. In the interphase before the reduction division these pairs join together, and the division itself separates the bivalent chromo somes into their component halves so that each daughter cell con tains either a, or a' either (3 or /3', either y or y', either 3 or b', and either X or Y, making five in all, one representative of each pair. Thus the male will contribute at fertilization one representative of each pair, and the female will contribute at fertilization one member of each pair, so that the members of any given pair that are separated in the reduction division are of paternal and ma ternal origin respectively. Thus the formation of the gametes involves with respect to each pair of chromosomes the segregation of its maternal and paternal components.

This conclusion, abundantly attested by studies of heteromor phic chromosomes in a great variety of animals and plants, and first clearly recognized through the work of Strassburger on plants and Sutton on an insect Brachystola, is of far-reaching theoretical importance. Its recognition by Sutton synchronized with the re discovery of Mendel's principles by Correns, Tschermak and de Vries, and their extension to animal inheritance by Bateson and Cuenot (1902), and the rapid development of experimental breed ing in the years that followed may in part be attributed to the fact that the microscope could now reveal the existence of visible units which behave in a manner precisely analogous to the ma terial entities which Mendel had called factors. A single illustra tion must suffice to indicate this correspondence. In a cross be tween pure wild stock of the fruit fly Drosophila and the sport distinguished by the vestigial condition of the wings, the first crossbred generation are all long-winged flies like the wild parent, but, unlike the latter, when mated among themselves, they pro duce offspring, one-quarter of which are pure-breeding vestigial winged flies, one-quarter pure-breeding wild type flies and the remaining half, like their parents of the first crossbred generation, impure, giving offspring one-quarter vestigial-winged, etc., if mated inter se. The impure long-winged flies of the first crossbred generation receive something from their wild type parents in virtue of which they have long wings, and something from their vestigial-winged parents in virtue of which they have offspring which have vestigial wings ; but the pure vestigial-winged parent and the pure wild type parent receive similar contributions pre sumably from both of their respective parents. Hence we may denote the wild type parent of pure stock by the symbol VV and the vestigial-winged sport of pure stock by the symbol vv, while the crossbred long-winged flies must be denoted by the symbol Vv. If the gametes may receive either the maternal or paternal ele ment of this association then, when two crossbred flies are mated, each will contribute gametes V or v. Thus if these gametes are produced in equal numbers the possible combinations on fertiliza tion are vv, VV, vV and Vv in equal numbers. Vv and vV by hypothesis will be long-winged and impure, while vv and VV will be pure vestigial- and long-winged respectively, so that one-half the offspring of the crossbred flies will be long-winged and impure, one-quarter pure long-winged and one-quarter pure vestigial winged. Thus the quantitative results of breeding experiment are interpretable on the assumption that the material units (factors or genes), on which inheritance depends, are distributed in such a way that each gamete receives either the paternal contribution or the corresponding maternal contribution to the determination of a given character. In other words, the formation of gametes in volves with respect to (a) each pair of chromosomes, (b) each pair of factors inferred from breeding experiment, the segrega tion of its maternal and paternal components.

In arriving at this conclusion one tacit assumption has been made, namely, Rabl's doctrine of the persistent individuality of the chromosomes. In the living cell, separate chromosomes can not be detected in the interphase. But the faithful correspondence of the pictures obtained by expert fixation in other stages with what can be seen and photographed in the living condition does not make this objection of overwhelming importance. There are so many phenomena of chromosome behaviour that can be inter preted on no assumption other than that they do preserve their separate entities in the interphase that it is for the present a very justifiable assumption. In some animals and plants the chromo somes can be separately envisaged in the attenuated or diffuse con dition they display in the interphase in fixed preparations. In any case they become again distinguishable at prophase in a precisely analogous orientation to that which they display in telophase, and sometimes in nuclei with asymmetrical configuration the appa rent dissolution and resolution of a chromosome of the same char acteristics can be referred to an identical position in the nucleus. Naturally the adequate discussion of this question leads into highly technical issues, and the reader who wishes to obtain some idea of the accumulated evidence of a large number of different investi gators who have studied this issue may refer to such works as those of Wilson, Doncaster and Agar. The considerations in favour of the view that each chromosome of the prophase corre sponds to a similarly constituted chromosome in the preceding telophase may be summarized briefly as follows : (r ) Actual con tinuity can be observed in a number of plants as shown by Schwarz (1892), Zacharias (r 895) and more recently by Over ton, Rosenberg and Stout (ii) ; (2) The orientation of the chromosomes in the prophase is precisely like that in the preced ing telophase, a fact well shown in Digby's work on Osmunda, McClung's work on Orthoptera and Boveri's work on the lobed nuclei of Ascaris; (3) The numerical relations are consonant with the hypothesis of persistent individuality in abnormal fertilization phenomena such as polyspermy and species hybrids (Beveri, Fed erley, Baltzer). The hypothesis of Rabl thus permits of predic tions that could not be inferred without its aid. Conceivably a mechanism might exist to manoeuvre the chromatic constituents of the nucleus in such a way as to reproduce similar configurations in successive cell divisions without implying any continuity or integrity of these configurations. But the critics of the more generally accepted view have failed to give any indications of the nature of such a mechanism.

Sex Determination.

In the case of the stone fly cited above, there is one circumstance that may have already given rise to a query .in the mind of the reader. This is the existence in many animals of an unequally mated pair of chromosomes, the XY pair. When this occurs, it occurs in one sex only ; in the alternate sex there is a corresponding equal pair (XX). In birds and Lepidop tera (butterflies and moths), the female is the XY, the male the XX individual. In other animals the male is usually found with sufficiently careful measurement to have an unequal (X V) pair which is equally mated in the female (XX). During the '9os some animals were found that had in one sex an odd number of chromosomes : this at first sight seemed to conflict with the numer ical constancy of the chromosomes. In the early years of the present century the American zoologists, Montgomery, McClung, Wilson, and others, provided the key to an understanding of the problem. In all such cases the alternate sex has one more chromo some. Thus the male of the cockroach Periplaneta americana has 33 (32+X), the female 34 (32-+X) chromosomes. The eggs will all have 17 chromosomes, one-half of the sperm will have 17, the other half 16 chromosomes, if a sperm of the former class fertilizes an egg, the individual produced will be a female (r 7+ 17=34), and if a sperm of the second type fertilizes an egg, the individual produced will be a male (17+16=33). Similarly with the XY chromosomes. The male of the human species has 23 equally paired and one unequally mated (XY) pairs of chromo somes in the unreduced nuclei. Thus two types of sperm are pro duced, X-bearing and Y-bearing respectively, the one female-pro ducing, the other male-producing. The modern theory of sex determination fits in well with many biological facts, and is con firmed by two independent lines of evidence, one of which will be discussed at length later. The other may be mentioned here. In species having an XY pair in the male, measurement of the sperm heads show two distinct modal values around which the observations group. This suggests the possibility that by mechan ical or other methods it may be possible eventually to separate seminal fluid into portions containing predominantly one or other type of sperm, the X-bearing or Y-bearing. If this could be done the control of the sex ratio would be experimentally realizable.Many medical men still adhere to the belief that the sex of human offspring depends upon whether the egg fertilized is derived from the right or left ovary. Apart from the very conclusive evi dence we have from other sources that this view is wrong, it is demonstrably false in other mammals, where removal of the ovary of one side does not affect the sex ratio. In this connec tion it is pertinent to recall the words of Sir Thomas Browne : "And therefore what admission we owe unto many conceptions concerning right and left requireth circumspection. That is how far we ought to rely on the remedy in Kiranides, that is the left eye of a hedgehog fried in oil to procure sleep, and the right foot of a frog in a deer's skin for gout ; or that to dream of the loss of right or left tooth presageth in the death of male or female kindred, according to the doctrine of Artemidorus. What verity there is in that numeral conceit in the lateral division of man by even and odd, ascribing the odd unto the right side and even unto the left; and so, by parity or imparity of letters in men's names to determine misfortunes on either side of their bodies, by which account in Greek numeration Hephaestus or Vulcan was lame in the right foot, and Annibal lost his right eye. And lastly what substance there is in that auspicial principle and fundamental doctrine of ariolation, that the left hand is ominous and that good things do pass sinistrously upon us, because the left hand of man respected the right hand of the gods, which handed their favours unto us." When the sex chromosomes were first discovered the hypothesis outlined seemed to conflict with the well-known fact that many familiar animals change their sex. It may, however, be presumed that whatever influence the X chromosome exerts, required the proper co-operation of external agencies; indeed the facts of sex transformation fit in very well with the hypothesis, when they are studied more carefully. Thus Crew (r 92r) found that, whereas the offspring of a normal mating in frogs produces the customary I–I ratio of male and female offspring, a quite different result occurs when we mate with a normal female a male that started its life as a female. Crew reared a generation of 700 offspring of such a cross all females. If the transformed male were, as its former life would suggest, an XX individual in disguise, it could produce no Y-bearing sperm and therefore no male offspring.

In applying the results of cytological studies to the interpreta tion of breeding experiments one group of characters studied by Morgan and his colleagues in the fruit fly Drosophila is of particu lar interest, and is specially significant in relation to the foregoing remarks. A single instance will suffice to make clear the character istic feature of this group. In the wild fruit fly the eye is red; there is a mutant (sport) form with white eyes. A red-eyed fe male crossed with a white-eyed male yields an composed ex clusively of red-eyed individuals; but in the F2, which consists of three reds to one white, all the females are red-eyed, and all the white-eyed individuals are males. Now when a pure red-eyed male is crossed with a white-eyed female the result is quite dif ferent ; all the females in the as before have the dominant redeye; but the males are white-eyed. When the are mated inter se, equal numbers of white-eyed and red-eyed females and males are produced. The inability of the male to transmit red to his offspring of the same sex is readily explained on the assumption that the red gene is linked to something which, if present in the zygote in duplicate, leads to the production of a female, and if present in the zygote unpaired (diagram) leads to the production of a male ; the red-eyed male produces sperm of two kinds, one bearing the "red" gene destined to fertilize an egg which must become a female, and one which cannot bear the red gene and which is destined to lead to the production of another male. This implies that sex itself is pre-determined by genetical factors for which one sex is constitutionally impure, so that a i–r sex ratio is maintained by the normal consequences of mating pure and impure types. Since in this case maleness is the state associated with the single condition and femaleness with the duplex state as regards the sex-linked genes, the male may be represented, symbolically, as Ff and the female as FF, using the symbol F for that which determined femaleness. Actually there is in Drosophila a pair of chromosomes in the female (XX) of equal size represented in the male by an unequally paired chromosome. Thus the female pro duces eggs all having an X chromosome and all capable of carry ing the hereditary factor or gene for the red-eyed condition, while the male produces two sorts of sperm, one having an X chromo some and capable of carrying the gene for redeye, and one hav ing a Y chromosome. Clearly the behaviour of the hypothetical units indicated by the symbols F and f corresponds to the be haviour of the actual chromosomes X and Y. This type of sex linked inheritance occurs in most insects and in mammals; and for reasons given later may be anticipated to occur in practically all higher bisexual animals except birds and Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) .

Sex-linked inheritance was indeed first studied by Doncaster (1905) in the currant or magpie moth, Abraxas. Two varieties of this moth are distinguished by the colour pattern of the wings as grossulariata and lacticolour. If a lacticolour female (in which the wings are of a creamy tint) is mated with a grossulariata (dark-winged) male all the resulting offspring show the dark gros sulariata wing pattern. The grossulariata gene is dominant to the lacticolour gene. When the reciprocal cross is made between a lacticolour male and grossulariata female from a pure stock the grossulariata pattern only appears in the male offspring, all the daughters being of the lacticolour type. It would seem then that the female produces two sorts of gametes, one kind which can carry the factor for the grossulariata pattern and is destined, if fertilized, to become males, and another kind which cannot carry the grossulariata factor and is destined in the ordinary course of events to become females. One may say that the female moth is for certain factors or genes constitutionally heterozygous, and that the grossulariata factor is linked to another factor which, if pres ent in duplicate, determines maleness. Thus the sex of the moth appears to depend on the presence of a double or single component which, when present in duplicate, leads to the production of a male, and may therefore be called the factor for maleness ; and a corresponding type of sex-linked inheritance occurs in birds (canaries, doves, fowls), as shown by the work of Pearl, Bateson, Punnett and others. A straightforward case is provided by the inheritance of colour pattern in the Black Langshan and Plymouth Rock breeds of domestic fowl. If an unbarred hen is mated with a barred cock all the offspring are barred, but only the cockerels are barred in the offspring of the reverse cross between a barred hen and an unbarred cock. Here again the female seems to form two sorts of eggs—one which can carry the barred factor and will become cockerels, and one which cannot bear the barred factor and will develop into pullets. It is thus of no mean interest that the observations of Seiler (1914) and Hance (1927) demonstrate the existence of a pair of chromosomes (XX) in the male of moths and birds unequally mated in the female.

Cytology and Heredity.

The cell doctrine profoundly in fluenced the discussion of the hereditary process long before the chromosome hypothesis emerged in its modern form. In at tempting to understand the tenacity with which the Lamarckian idea, that is to say the supposed inheritance of acquired charac ters, has persisted in biological thought, it must be borne con stantly in mind that embryology is the most recently developed branch of anatomical science. Until the classical researches of van Baer and Meckel in the early part of the i 9th century, the prevailing idea about development was that each organism is from the very first complete in all its parts and only needs growth to make its minute structure manifest to the eye. Caspar Wolff had, it is true, made observations as early as 1759 which led him to enunciate the "epigenetic" as opposed to this "evolutionary" view. He sought to show that the hen's egg is at the beginning without gross anatomical organization, and that structural organ ization within the egg is a gradual development. Nevertheless his work was disregarded at the time, and it was not till van Baer's researches were published about the same time as the formula tion of the cell doctrine that a new attitude to the process of de velopment manifested itself in biological thought. Up till this time the conception of inheritance in biology had been closely analogous to the legal one. The parent was supposed to hand on its characters to its offspring in the same way as the well-to do hand on their belongings. With so erroneous an idea of the nature of development to guide them it is little wonder that the Lamarckian idea flourished. With the discovery of fertilization years after the Origin of Species was first issued, a new orien tation was necessary. Henceforth everything implied by the term inheritance must refer to something contained in either the egg or the sperm, which constitute the only link between parent and offspring. This more concrete approach to the problem of trans mission necessitated a reinvestigation of accepted beliefs, and it is more than a historical accident that Weismann's challenge was thrown to the scientific world contemporaneously with the dis covery of the intimate nature of the processes of fertilization and the maturation of the germ cells.Since the ovum and sperm each arise from a single cell of the parent body, the death of the individual "involves no breach in the continuity of cell-divisions by which the life of the race flows wards." In challenging the Lamarckian doctrine Weismann wrote (1883) : "In taking this course I may say that it is impossible to avoid going back to the foundation of all phenomena of heredity and to determine the substance with which they must be connected. In my opinion this can only be the substance of the germ cells; and this substance transfers its hereditary erties from generation to generation at first unchanged and always uninfluenced in any corresponding manner by that which happens during the life of the individual." Proceeding from this point Weismann endeavoured to show that the inheritance of acquired characters was a logical absurdity. Nevertheless experiments lowed as an inevitable consequence, and two generations of ful experimental work have been quite unsuccessful in ing any authentic evidence for the view that Weismann challenged (see LAMARCKISM). To Weismann's influence more than to any other scientist may be attributed the rapid development of cytology during the last two decades of the i 9th century, minating, when Mendel's work was rediscovered, in the ment of the chromosome hypothesis. Following Nageli, mann himself focussed attention on the importance of the mosomes in hereditary transmission at an early date. But it is important to note that Weismann's ideas were bound up with an entirely erroneous conception of the modus operandi of the chromosomes in the development of the organism. Like Roux, Weismann regarded development as a process of unpacking of the determinants or hereditary factors and distribution of priate units to different regions. Experiment shows that the tary potentialities of different cells of a developing organism are essentially similar, and the fact that all cells of the body have a similar set of chromosomes constitutes no difficulty in the way of acceptance of the chromosome hypothesis in its modern form, as some critics (Dobell and others) appear to think. By the chromosome hypothesis is meant the view that locates the material units of Mendelian segregation in the chromosomes. The respondence of the behaviour of the two was already stated plicitly by Lock as early as i 906, and the work on sex-linked inheritance that grew out of Doncaster's labours from 1906-12 greatly reinforced the idea. But in 1912 the work of Morgan's school placed the question on an entirely new basis by suggesting a cytological basis for "linkage." Mendel had studied inheritance of several different characters simultaneously, and found that they behaved as though they were quite independent, so that at first it seemed as if an almost infinite number of material units be having like the chromosomes would be required to interpret the phenomena of heredity in a single species. This was an obvious obstacle in the way of accepting the view stated above. Bateson and Punnet first showed in sweet peas that some hereditary characters stick together in transmission, as if they were borne on the same chromosome. This is the phenomenon known in genetics as linkage, and one that raises the most interesting issues in relation to descriptive cytology at the moment.

Linkage and the Chromosome Hypothesis.

As an illus tration of linkage the following example from the work of Mor gan and his colleagues since 1913 must suffice. There is a mutant or sport of the fruit fly with black coloration of the body. Cross ing with pure wild stock flies which have grey bodies gives re sults analogous to those obtained with crosses of vestigial-winged and wild stock individuals. The first crossbred generation (F1) are grey; these crossbred flies mated inter se have offspring grey and black in the ratio 3-1. When a "black" fly with vestigial wings is crossed back to the wild parent stock, the individ uals are grey with long wings as in the ebony vestigial cross. Now if the males are mated with females of the black vestigial type the entire progeny are either grey with long wings or black with vestigial wings (r-1) . The same result is obtained in the generation of a cross between a black mutant with long wings and a normal grey fly with vestigial wings, all the progeny being grey with long wings. But if these males are crossed back to the black vestigial females, the offspring are one-half grey with vestigial wings and one-half black with long wings. It is clear in this case that both results are capable of being inter preted as before if we assume that a single pair of structural units is involved in the distribution of both pairs of factors among the gametes. If now, instead of crossing back the males to the double recessive females, the reciprocal mating of the females to the double recessive male type is made, the re sult is slightly different. Taking first the case where both the recessive factors (black and vestigial) were brought in from the same parent, it is found that the back cross of the females instead of giving 5o% black vestigial and 5o% grey long, pro duces 41.5% black vestigial and 41.5% grey long, together with 8.5% black long and 8.5% grey vestigial. Similarly if the females of a cross in which only one recessive factor is intro duced by each parent are back-crossed to the double recessive male, the progeny, instead of being 5o% black long and 5o% grey vestigial, are 41.5% black long and 41.5% grey vestigial together with 8.5% black vestigial and 8.5% grey long. The numerical results are here amenable to interpretation on the assumption that there exists a single pair of structural units carry ing both pairs of factors; but that in 17% of the cases a crossing over of material occurs between the two components. It must not be inferred from this illustration that complete linkage is characteristic of the male and partial linkage of the female in general among animals. The phenomena of complete linkage find a ready explanation in the assumption that the linked factors are borne on identical chromosomes.The appearance of a certain number of exceptional individuals in the F2 generation when the first crossbred parent is a female is explicable on the assumption that, when the chromosomes pail in the reduction division, there is, in a certain percentage of cases, an exchange of materials. This assumption must be treated warily. When, however, the question is probed more thoroughly the ex planation becomes more acceptable. In the first place we have to reckon with the fact that the several hundreds of mutant charac ters in Drosophila which have been studied by Morgan and his colleagues Muller, Sturtevant, Bridges, and others, all fall into four groups. Members of the same group are linked ; members of different groups are transmitted independently of one another, as in the grey-ebony, long-vestigial cross. The fact that there are four such groups, and only four, and that the number of pairs of chromosomes in Drosophila is four, the fact also that one group of linked factors, the sex-linked characters, can be so definitely co-related with the behaviour of the XX, XY pair, can hardly be a mere coincidence.

Now the chromosomes do become twisted in the process of pairing (synapsis) which precedes reduction. And since the split takes place so that it is longitudinal in one plane, some cytologists have actually concluded that crossing over of corresponding lengths from homologous chromosomes takes place, when the split occurs. (This means that although the chromosomes in such a case do not retain their individuality, the separate factors [genes] are unaffected in this respect.) If this were so, it would not be unnatural to suspect that genes dependent on material located in closely adjacent parts of a chromosome would stick together more often than genes located in more remotely located parts of a chromosome, or that, in other words, the extent of crossing over would be related to the loci of the genes. This im plies the possible existence of a quantitative relationship between the cross-over percentage of different pairs of linked factors. Such a relation exists. When the cross-over values of different pairs of factors within a linkage group are scrutinized, they are not found to present a haphazard assemblage. On the contrary they can be arranged in a definite arithmetical series. That is to say, if A and B have a cross-over value of 5% and B and C have a cross-over value of 7%, the cross-over value of A and C is either 12%, the sum, or 2%, the difference. Therefore, on the assumption that the chance of two genes being separated is proportional to their distance apart on the chromosome, the genes of Drosophila mutants may be arranged in linear series each of which is a map of one of its four pairs of chromosomes. The perfect mathe matical regularity of this arrangement is too striking to permit of reasonable doubt regarding the truth of the conclusion.

For illustrative purposes let us take the transmission of two other recessive mutant factors located on the second chromo some of Drosophila, i.e., on one of the large curved pairs in fig. 26. The mutant with purple eyes is a simple recessive to the wild type condition. The mutant with the bent-up "curved wing" is a simple re cessive to the normal long-winged condi tion. In a cross between individuals involv ing the vestigial and curved-wing charac ters the cross-over percentage was 8.2, based on a generation of 1,861 flies. The cross-over value for the purple and curved factors was 19.9, based on a generation of 61,361 flies. The expected cross-over between vestigial and purple factors would therefore be 11.7. In an actual experiment in which 15,210 flies were reared, the cross-over value between purple and vestigial proved to be 11.8. The cross-over value for black and purple was 6.2, based on a generation of 51,957 flies. The expected cross-over value for the black-vestigial cross would therefore be 6.2+11.8=18. In actual experiment, based on 23,731 flies, the value 17.8 was obtained.

The hypothesis outlined is sustained by a further considera tion. There is the very strongest reason for associating the sex linked characters with the X chromosomes, or, as they are some times called, the first chromosome pair in Drosophila. Now, the same relations apply within the X or first chromosome group. The yellow body colour of the mutant known as yellow is a recessive sex-linked character ; so also is the small type of wing known as miniature. Now, when a miniature male is crossed to a yellow female we obtain, as we should expect, normal females and minia ture males. When these are interbred we should expect to get only miniature individuals of both sexes, and 25% normal females in addition, if there were no crossing over between adjacent parts of the same chromosome pairs during reduction. But actually, a certain proportion of normal males and yellow miniature females appear. The amount of crossing over is 34.3% (21,686 flies). Between yellow and the sex-linked white-eye factor the cross over percentage is i • 1. The expected cross-over value for minia ture white is 34.3-1.1 or 33.2. The actual value based on a gen eration of 110,701 flies is 33.2.

Synapsis and Linkage.

The conception of crossing over in the reduction process offers no difficulty, if, as is now generally held with regard to animals, the bivalent chromosomes of the first reduction division are formed by the side-by-side union (para synapsis) of the elements of each chromosome pair. At present the demonstration of actual transposition of adjacent portions of paired chromosomes cannot be observed microscopically with any degree of certainty. The details of the reduction process have on this account, however, acquired considerable theoretical interest and attracted the attention of many investigators. An extensive nomenclature has been introduced for descriptive purposes in this connection, and some of the more commonly used terms may be mentioned, following in the main the system introduced by Von Winiwarter 0900). Immediately after the last telophase preced ing the reduction (also called heterotype or meiotic) division, the chromosomes in the form of attenuated loops with their free ends orientated towards one pole present the appearance of a bouquet : this is the leptotene stage. These are seen to be laterally associ ated in pairs in the succeeding zygotene (Gregoire, 1907) or amphi tene (Jannsen, 1905) stage. They next become shorter, more inti mately associated and contracted to one side of the nucleus, so that the number of loops is now, by fusion of adjacent pairs, half the number in the leptotene stage. This is the pachytene stage. The loops now assume a well-marked longitudinal fission in the plane of fusion, become detached from their polar orientation, and often display twisting of their longitudinal halves. This appear ance is known as the diplotene or strepsitene stage. When the spindle appears and the nuclear outline is lost, the longitudinal halves of the diplotene filaments have been drawn apart and very much condensed to form the characteristic heterotype chromo somes of the first reduction division. The whole series of events is represented diagrammatically in fig. 23. While this is now gen erally admitted to be in broad outline typical of animals of both sexes, the phenomenon of reduction in plants is still subject to much controversy. Perhaps it is worthy of mention, however, that in plants the difficulties of securing satisfactory postmortem preservation (fixation) owing to the wall of cellulose that sur rounds the cell makes it more difficult to obtain a clear picture of the delicate stages of the reduction process than is the case with animal cells. Some botanists maintain that the pairing of the chro mosomes is an end-to-end union (telosynapsis). Such a view offers no material basis for the interpretation of the linear arrangement of the genes, a principle which has now been shown to apply to linkage in plants as well as in animals. More work still remains to be done on synapsis in plants before this difficulty can be surmounted.

Validity of the Chromosome Hypothesis.

It is now appro priate to sum up the present state of the evidence in favour of the chromosome hypothesis.I. Breeding experiments lead to the conception of material units present in the fertilized egg in duplicate, and segregating before the formation of the gametes into maternal and paternal compo nents, one member of each pair and one only being present in each gamete. As is well known, the chromosomes in all animals and plants are present in the fertilized egg in twice the number found to be present in the gametes. Furthermore, in many animals (and plants) from the most diverse phyla, the chromosome complex of a species is characterized not only by a definite number, but a definite configuration. It is possible to distinguish among the chromosomes pairs of different sizes and shapes (this is true of man and many mammals), and the maintenance of this constant configuration implies that when reduction takes place one member of each pair passes into each gamete. In other words, the chromo somes are present in the fertilized egg in pairs, segregating in the formation of the gametes into paternal and maternal components, one member of each pair and one only being represented in each gamete.

2. The material units on which hereditary transmission depends are associated in groups, the members of which are independently segregated with reference to members of other groups. There are four such groups in Drosophila; and in Drosophila there are exactly four pairs of chromosomes. No organism is known in which the number of linkage groups is numerically greater than the number of pairs of chromosomes. Moreover, it may be men tioned that the occurrence of chromosome abnormalities in a few exceptional cases such as the triploid intersexes of Bridges men tioned below has made it possible to identify one small linkage group in the fruit fly with the small fourth pair of chromosomes in Drosophila as definitely as we can locate the X-linked characters with the X or first chromosomes. The two remaining large linkage groups are therefore associated with the two remaining large curved pairs of chromosomes in Drosophila.

3. Lastly with respect to one group of linked characters the sexes are differently constituted. Sex-linked inheritance has been described in several groups of the animal kingdom, including mam mals; there are several such cases in man where, as in Drosophila and the cat, it is the male that produces two types of gametes. In several hundreds of animal species, from the most widely divergent groups, it is now established that one pair of chromosomes which is equally paired in one sex is represented in the other sex by a single member, or a pair of unequal elements.

In this field the coincidence between the genetic and microscopic data has been illustrated still further by the phenomenon of "non disjunction" described by Bridges in connection with several sex-. linked mutant characters, of which our original instance of white eye colour will serve as an example. There appeared among t'he white-eyed mutant stock of Drosophila certain strains of which the females, when crossed to normal red-eyed males, gave a certain proportion of red-eyed males and white-eyed females, in addition to the usual red-eyed females and white-eyed males alone. When the white-eyed female offspring of such abnormal crossings were mated back to red-eyed males, they, in their turn gave all four classes—red-eyed males and females, white-eyed males and fe males. The white-eyed females behaved like their mothers, giving abnormal results in all cases. Certain of the red-eyed females gave normal and half-abnormal results in crossing. Of the male progeny the red-eyed individuals were normal, whereas only half the white eyed individuals were normal, the remainder begetting daughters whose progeny was exceptional. Bridges found that in the abnormal white-eyed females the chromosome complex of the dividing cells showed a Y element in addition to the XX pair.

This is explicable on the understanding that at reduction of the eggs in a certain proportion of cases the X elements failed to dis join, so that the ripe egg contained either two X elements or none at all. If we represent the sperms of a red male as X' or Y, two additional types of individuals will result from the fertilization by a Y or X' sperm respectively, an XXY or white female, and X'O or red male. This accounts for the exceptional individuals in the and accords with the facts elicited. Next consider the results of back-crossing these XXY abnormal white females to a nor mal X'Y male. According to whether the X elements segregate with respect to one another or the Y chromosome, the white females will lay four types of eggs—XX, Y, XY, X. If these are fertilized by a Y sperm which cannot bring in the red factor we get four types : (a) XXY—white females, which will obviously behave in the same way, thus agreeing with breeding experience; (b) YY—individuals with such constitution cannot exist ; (c) XYY—white males, which should produce XY sperms so that, in crossing with normal white females, daughters of the XXY type, producing exceptional progeny would result ; (d) XY—normal white males. When on the other hand, the same four classes of eggs are fertilized by an X' sperm carrying red factor, four red types of offspring would result as follows : (a) X'XX—a triploid female, which usually dies; (b) X'Y—normal red males; (c) X'YX—red females with abnormal offspring ; (d) X'X—normal red females. Thus, the non-disjunction of the X chromosome in the formation of the egg of some of the females of the parental white-eyed stock accounts for the entire series of exceptional genetic phenomena which occur in these strains.

Recently Bridges has shed further light on the genetical aspect of sex-determination by the discovery of non-disjunction in chromosomes other than the sex-chromosomes, sometimes referred to in contrast to the latter as autosomes. In an experiment in which a brown mutant of Drosophila was crossed back to a parental stock, a culture was obtained in which the individuals were almost exclusively females or sex intermediates. These "in tersexes" displayed intermediate sex-characters throughout, nota bly in the abdomen and in the sex-combs of the tarsal joint of the forelegs and also in the genitalia. On the whole they fell into two groups, one tending more to the female, the other to the male con dition. Genetical evidence led Bridges to conclude that for one group of genes at least the female individuals of these cultures were triploid, i.e., inherited a double instead of a single set of genes from their fathers. Microscopic examination of the germ cells revealed the fact that the second and third chromosomes were present in triplicate, while an additional fourth chromosome was present in some but lacking in others, there being thus two degrees of the triploid condition, that with three-fourth chromosomes being more female. The X chromosome was present in duplicate in the intersexes but the females possessed three X elements. Thus using the symbol A for the chromosomes (autosomes) other than the X chromosomes, and X for the sex-chromosomes, the genetical constitution of these intersexes and abnormal females were respectively 3A+ 2X and 3A+3X, as contrasted with the normal female constitution 2A+ 2X. Abnormal males were also found with the constitution 3A+X, as contrasted with the normal male constitution 2A+X. Therefore, if X :A = i or greater than r the individual is a female, if X :A=4 it is a male, but when X :A lies between 1 arid the intersexual condition is manifested (Oats, Oenethera, Datura.) The factorial hypothesis has aroused a good deal of hostility, not unnaturally, for it conflicts with many accepted speculations as to the evolution of living organisms, and disposes of not a few beliefs still professed by many. Nevertheless, the remarkable di versity of inherited characteristics, anatomical and physiological, with which it deals, the truly amazing correspondence between the conclusions derived from experimental and microscopic studies, and finally, the established fact that the nucleus is the only recog nizable cell-element which is universally contributed by the sperm to the development of a new individual can leave little room for doubt in the minds of impartial students of the subject that, in broad general outline, it takes within its compass all the essential phenomena of biparental inheritance.

Experimental Cytology.—Up to the present, the most spec tacular results of the study of cells have arisen by correlating descriptive observation with the conclusions derived from experi mental study of the physiology of inheritance. A promising field has been opened up during the past few decades by the experi mental study of living cells in relation to other aspects of physio logical science. All physiology having as its aim the interpretation of the properties of living matter, i.e., protoplasm, is in the final analysis concerned with the cell, but traditional physiology has studied cells statistically in the mass. Under the term experimen tal cytology may be included those investigations which apply special methods appropriate for the investigation of single cells as units of study. If the results gained so far are of somewhat limited application, there can be little doubt that experimental cytology is destined to make considerable contributions to the analysis of living matter in the long run.

Hitherto investigations under this heading have been concerned pre-eminently with two issues, the permeability of the cell to dis solved substances underlying all the material exchanges on which its chemical activity depends, and the physical properties of the different parts of the cell (elasticity, viscosity, etc.), or of the same parts in different phases of cell activity. Following the work of Overton (1904) a large number of researches have been made upon the penetration of dyes into living cells under different condi tions as a criterion of permeability. Others, following the classical researches of Pfeffer and de Vries, who initiated the study of the physical phenomenon of osmosis, have used the swelling or shrink age of cells in solutions of different concentrations to obtain light on differences in permeability. The action of centrifugal force on granular constituents (Heilbrunn) or magnetic force on particles of iron forced into the cell (Heilbronn and Seifriz) has been employed to study changes in viscosity of protoplasm. None of these methods is entirely satisfactory, and a new approach to the study of such problems has lately been opened up by the methods of microinjection and microdissection (see PROTOPLASM) per fected by Barber, Kite, Chambers, Peterfi and others. It is now possible to inject living cells with a glass needle of o•0005mm. bore, and to remove portions of the nucleus of a cell by these devices. Finally the growth of cells has become a new field of active investigation as the result of the methods of tissue culture developtd by Ross Harrison, Carrel and other workers in America. So far, however, progress has been most conspicuous in the inven tion of methods of assailing the difficult problem of studying such small structures rather than in the theoretical results.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-W. E.

Agar, Cytology (1920) ; E. V. Cowdry, GenBibliography.-W. E. Agar, Cytology (1920) ; E. V. Cowdry, Gen- eral Cytology (Chicago, 1924) ; L. Doncaster, An Introduction to the Study of Cytology, with bibl. (2nd ed. 1924) ; E. B. Wilson, The Cell in Development and Inheritance (3rd ed., rev. and enlarged 1925).(L. T. H.)