Czechoslovakia

CZECHOSLOVAKIA was an independent republic in Cen tral Europe, proclaimed on Oct. 28, 1918, and confirmed by the peace treaties after the World War. It comprised the lands of the ancient kingdom of Bohemia (q.v.), Slovakia (q.v.) and the autonomous territory of Ruthenia (q.v.). After having been de prived of about one-third of her territory and transformed into a federated state of the Czechs, Slovaks and Ruthenians in Oct. 1938, this new Czecho-Slovakia or the Second Republic, as it was called, ceased to exist in March 1939, Germany annexing the lands of Bohemia, Slovakia becoming nominally independent and Ruthenia incorporated into Hungary.

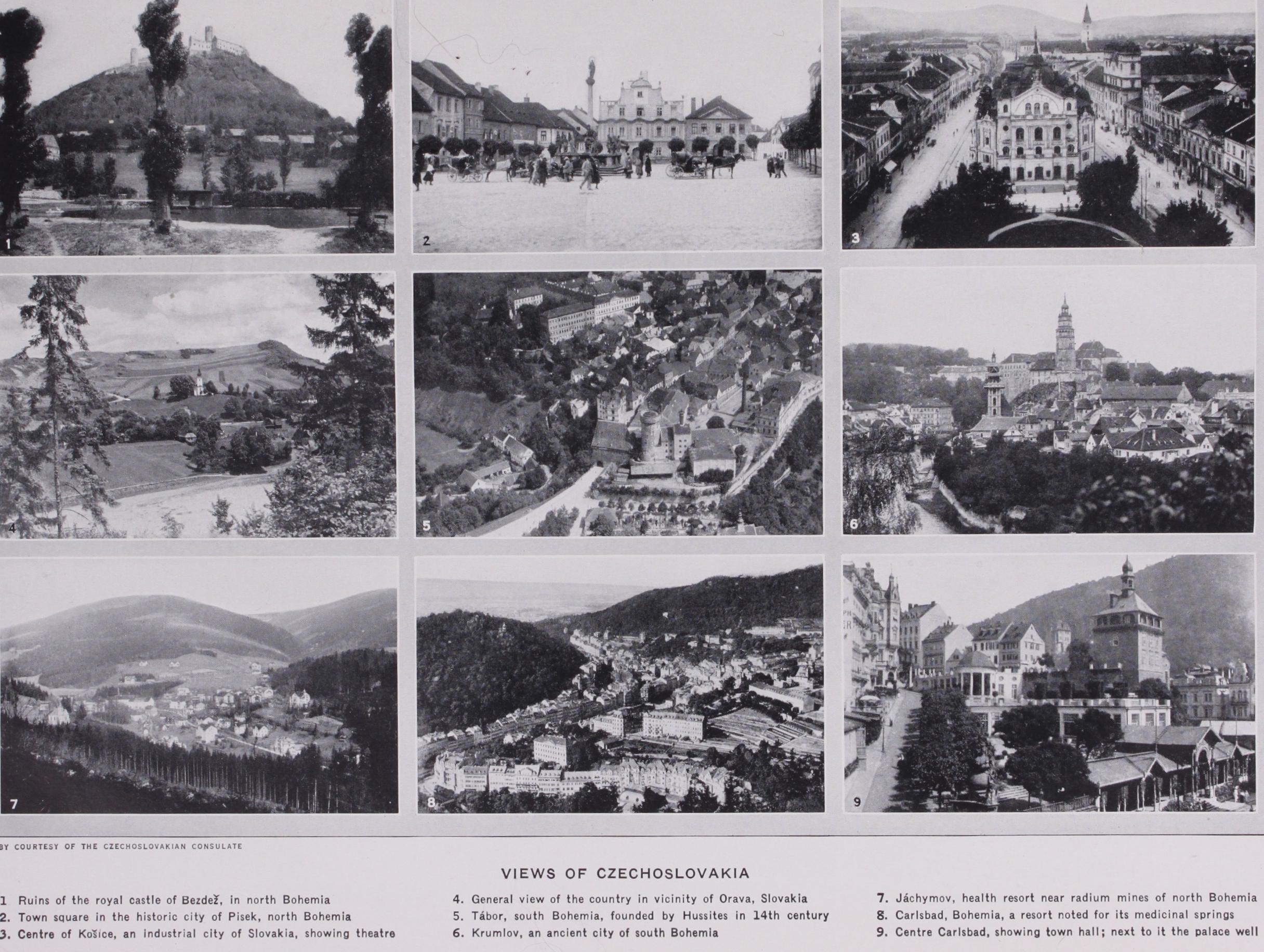

During her existence Czechoslovakia occupied a position of greatest strategic and political importance in the heart of Europe. The territory it occupied lies athwart a maze of frequented routes and forms a zone of contact between the Germanic and Slav worlds. It comprises two highly contrasted types of land form, each having a characteristic natural endowment. One, the old resistant upland region including Bohemia and parts of Mora via and Silesia, on account of the surrounding mountain ranges a natural bastion in Central Europe, gravitates mainly towards the North sea, is rich in mineral wealth and has deeply experienced the force of French and Germanic cultural influences, which are reflected in its advanced agriculture and industrialization, dense population and network of communications, and the modernism of its outlook which is definitely Western, progressive and demo cratic. The other, the folded ranges of the Carpathians (q.v.), has been naturally and politically drawn toward the Danube and the less progressive pastoral and agricultural region of Europe. Here, a sparse and disseminated population still clings to the old cus toms and primitive methods which are fostered by an isolation in mountain-girt basins. The administrative problem, faced by Czechoslovakia, of reconciling the divergent interests within the country was difficult, and the shape and physical structure of the country combined to increase the severity of the task. The W.-E. length amounted to 594mi., whereas the breadth varied from 175mi., to less than 45 miles. The capital, Prague (q.v.), had a peripheral location and was difficult of access from the remote and self-contained eastern districts with which it had originally few affinities and whose wider contacts had been traditionally established in the direction of the middle Danube. In spite of these difficulties Czechoslovakia succeeded in building up a mod ern and progressive state based upon an appreciation of the de mands arising from diversity of natural endowment and historical experience and of the necessity of combining regional autonomy with the needs of a common protection of progressive standards of democracy and national development.

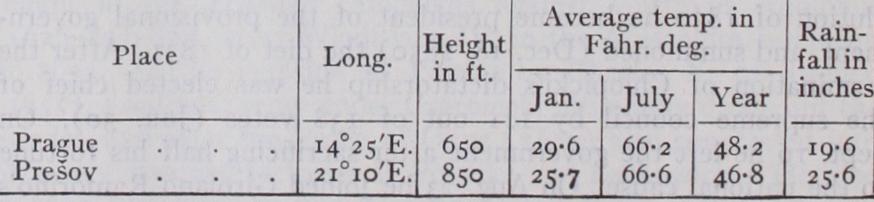

Climate and geographic formation are equally advantageous for agriculture. Climatically the country is transitional from oceanic to continental, as the following table shows: Variations in altitude and exposure, however, prevent uniformity and are important in agriculture. Thus, in the sheltered parts of the valleys of the Morava and Elbe and in the basins of the Car pathians that open southward the vine appears, while fruits and maize ripen and the lower slopes and plains offer striking contrasts to the raw and rainy highlands. As in the Eastern Alps enclosed basins suffer from inversions of temperature, but settlement and cultivation here rise to a height fully 600ft. above the limit in the former region. Precipitation is distributed advantageously for agriculture, fully two-thirds of the annual total falling in the spring and summer months. Heavy winter snowfalls are com mon in the highland regions and navigation on both Elbe and Danube is usually interrupted by ice for six to eight weeks.

Relief and climate combine to make Czechoslovakia one of the richest forest lands in Europe; conifers cover 55% of the forested area, deciduous growth 30%, the remainder being mixed wood land. The limit of tree growth varies from 5,000f t. in the Tatra mountains to 4,000f t. in the East Carpathians.

Population, Religion and Settlement.

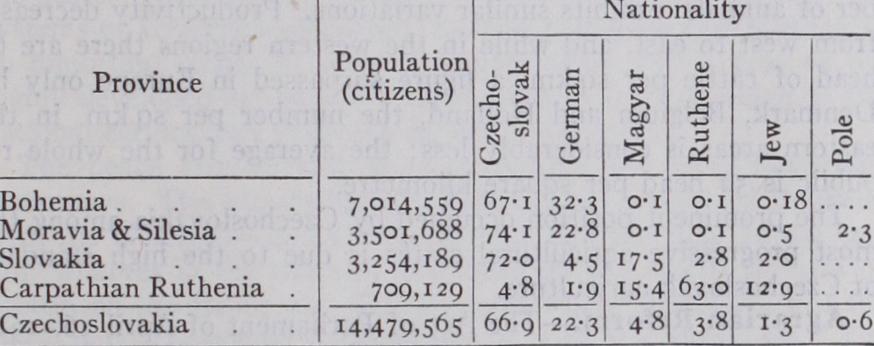

The population of the republic at the 1930 census was 14,729,536, of whom were foreigners. The following table shows the distribution of the native population according to provinces, together with the percentage figures for the principal nationalities represented :— This ethnic variety of the population presented a great diffi culty for Czechoslovakia. The young state, however, succeeded gradually in overcoming these difficulties by a strict application of its democratic constitution and of the principle of the equality of all citizens before the law, by providing all the minorities as amply with schools and cultural institutions in their own lan guages as the Czechoslovaks themselves enjoyed, and by trying to draw the minorities into active and constructive participation in the administration. Nevertheless the large German minority which lived mostly in compact blocks along the north-western and south-western frontiers in the most highly industrialized zones of the country,. and the Magyar minority living compactly in the southern plains of Slovakia contiguous with Hungary, continued to demand the grant of more extensive autonomy.

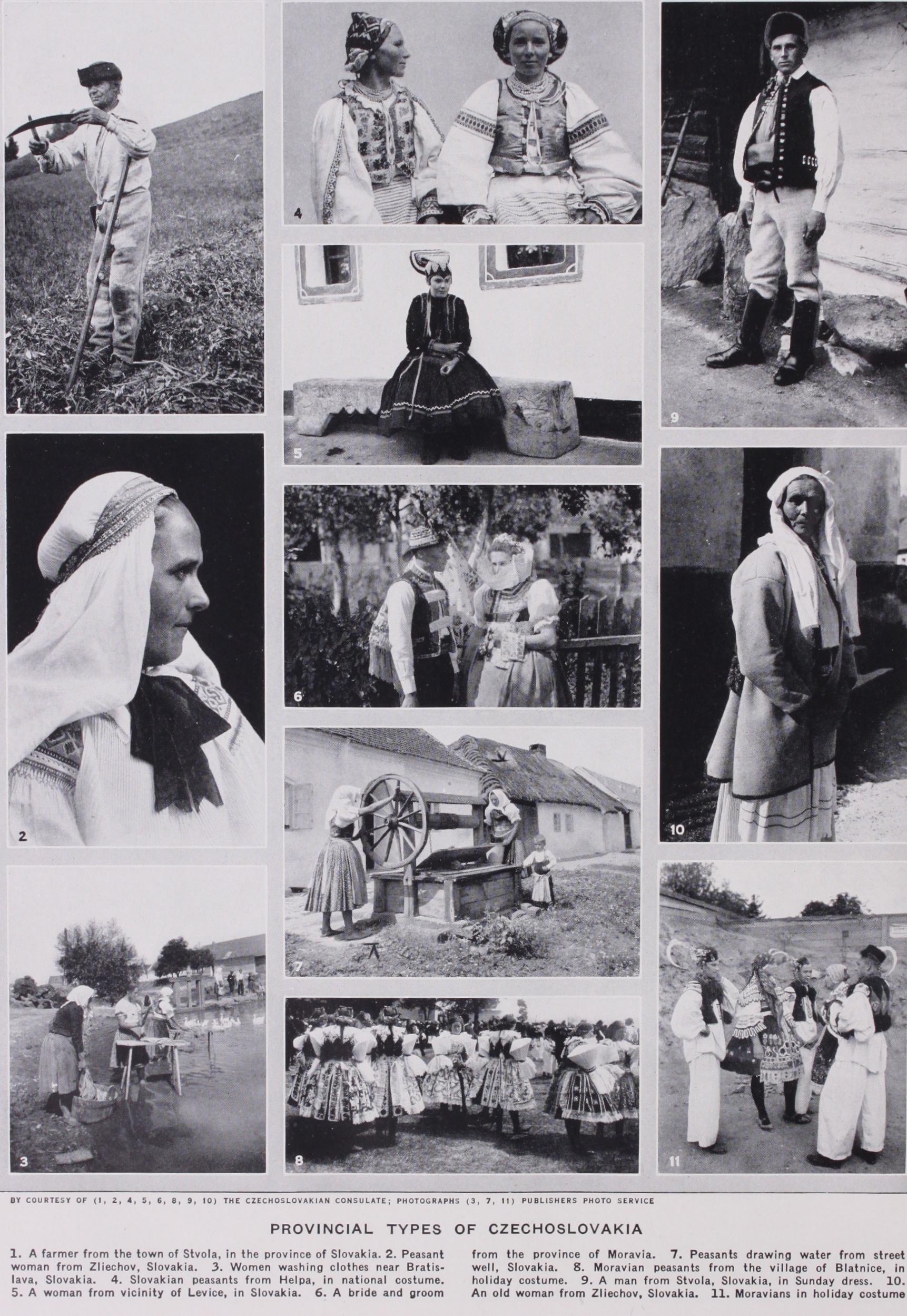

A similar demand for autonomy was also raised by part of the Slovak population which amounted to some 25% of the 9,688,77o persons classified as Czechoslovaks. The Slovaks, although racially and linguistically most closely related to the Czechs, nevertheless had been separated from them politically for many centuries and for historical as well as economic reasons their cultural level was in general much lower than that of the Czechs. In fact, passage eastward through the country marks a decrease in density of population consequent upon the change from industry to agri culture, a change from Roman to Greek form of religion, the ap pearance of more primitive house-types and a rapid increase in the proportion of illiterates. The house-types and village-forms reflect the differences of peoples and occupations as well as the physical contrasts from region to region. The modern ferroconcrete build ings of the industrialized western towns scale down to the rude wooden hutments of pastoral Ruthenia; the solid four-square form of the German varies only in the height and nature of its roof according to local climatic conditions and is an informative contrast to the smaller half-timbered house of the Czech and the thatched wooden structures of the Slovak. Correspondingly cus toms, social organization and dress vary considerably from those of advanced civilization to others that have scarcely altered through the centuries and recall vividly patriarchal times.

According to the census of 1930, 10% of the population lived in the five cities of over roo,000 inhabitants and 69.9% of the population lived in rural or small urban communities of less than 5,000 inhabitants. Of the whole population of the country 116 were men, 7,586,420 were women. The population had shown a considerable natural increase in the decade from 1920 to 1930. This natural increase amounted for the whole republic to 9.67%. Characteristically it was lowest in the most western part of Czechoslovakia, in the province of Bohemia, where it amounted only to 6.11%. And it rose from there until it reached 22.50% in the most eastern part of the republic, in Ruthenia.

The dominant religion was Roman Catholicism which was pro fessed in 1930 by 73.54% of the population. Of the other Chris tian denominations the Protestants numbered 7.67%, the Czecho slovak Church 5.39% and the Greek Catholic Church 3•97%. The number of Jews amounted to 2.42%. Their percentage was lowest in Bohemia with 1.07%, higher in Slovakia with 4.11% and high est in Ruthenia with 14.14%. (W. S. L.; H. Ito.) In no other department of the state activities was there so energetic an endeavour to ensure the independent existence of the new republic as in that of finance and currency. In this re spect there was a twofold aim : to achieve an equilibrium of the state finances and establish a stable currency. In both re spects the administration was highly successful.

The budget estimates for the four years 1935-38 amounted in millions of crowns: The total national debt amounted in 1938 to 47,094 million crowns as against 37,969 million crowns in the year 1933. Of this debt 36,843 million were internal debts, 8,251 million for eign debt, and 2,000 million note debt as a result of the monetary reform.

Currency.

One of the most important acts of the first Gov ernment of Czechoslovakia was the establishment of an inde pendent currency early in 1919. For this purpose it was decided to collect and stamp all the bank-notes of the Austro-Hungarian Bank, which were then circulating upon Czechoslovak territory, as well as the deposit accounts in Czechoslovak branches of the Austro-Hungarian Bank, totalling about 10 milliard crowns. Dur ing the process of stamping, about 2.7 milliard crowns were re tained as a compulsory state loan in order to reduce the amount of paper money in circulation, and the stamped bank-notes were declared to be state notes with a face value in Czechoslovak crowns. At the same time a temporary bank of issue was estab lished under the title of "Banking Office of the Finance Ministry." The stamped bank-notes were later replaced by independent state notes in equal proportion. In order to defray the value of the uncovered state notes and the deposit accounts taken over from the Austro-Hungarian Bank, a tax on capital was levied, the estimated yield of which was 7.5 milliard crowns. Of this sum nearly 5 milliards had been paid off by the end of 1927, leaving a remainder of the "State Notes Debt" of about 41 milliard Czechoslovak crowns. Neither was the Banking Office, managed by a board of directors appointed by the finance minis ter, nor was the National Bank of Czechoslovakia, which took over the former's functions on April 1, 1926, permitted to grant the state any loan, either direct or indirect.The financial and economic difficulties after the World War, the chaos prevailing in the currencies in the neighbouring states, and the comparative ignorance of Czechoslovakia abroad caused the exchange rate of the Czechoslovak crown to fluctuate up to 1922, although the financial administration continued to pur sue sound principles. From the year 1922, however, the exchange rate of the crown was stabilized at about loo crowns to $3 (U.S.). Thus, as a result of the energetic and judicious currency policy inaugurated by Dr. Ragin, the Czechoslovak crown maintained its stability and its relatively high exchange value at a period when the currencies of the neighbouring states were hopelessly unstable and depreciated. This caused Czechoslovakia to be de scribed as "an island in a sea of inflation." The National Bank of Czechoslovakia was set up in 1926 with a share capital of originally $12,000,00o which was, however, changed in 1934 to 405,000,00o crowns. The bank was under legal obligation to maintain the currency at the exchange level of 1 oo crowns to $2.9o–$3.o3 on the New York Stock Exchange. Thus Czechoslovakia was brought into line with the countries possessing a gold exchange standard. The gold and gold exchange cover ratio to the bank-note circulation and sight liabilities amounted to 42% on Dec. 31, 1926. In Oct. 1929 the final aim of the administration, to establish an effective gold standard currency, was realized and the value of the crown was fixed at 44.58 milligrams of fine gold. The gold content was, however, reduced in Feb. to milligrams, and was further reduced in Oct. 1936 to between 3o.21 and 32.21 milligrams. The cover of notes was reduced legally in 1934 to 25%, to consist only of gold.

Banking and Credit.—Among the oldest financial institu tions existing upon the territory of the former republic were the communal savings banks. As a result of the development of industry, notably about the middle of the i9th century, these were followed by deposit banks, and as agriculture continued to progress a number of co-operative institutions were established in the rural districts. At the end of 1935 the savings banks, the activities of which were strictly defined by special regulations, numbered 356, their total book deposits amounted to 18,810 mil lion crowns, as against 5,326 million crowns at the end of 1919. There were also in district agricultural deposit banks in Bohemia and more than 7,00o co-operative credit banks in ex istence.

In 1937 Czechoslovakia contained 23 joint-stock banks with a total paid-up share capital of 1,274 million crowns and 55 smaller establishments in the eastern part of the republic with a share capital of 252 million crowns. The financial and credit organiza tion of Czechoslovakia was supplemented by a State-managed postal cheque office in Prague, which was complemented by a postal savings bank.

Czechoslovakia had a highly developed system of public social insurance. On July 1, 1926, the Central Social Insurance Insti tution started its operations based on the capital scheme. This insurance covered accident, sickness, disability, old age and death. In view of the complex character the social insurance was not uniformly regulated. In the year 1935 the number of persons insured against sickness amounted to 3,051,000, those insured against disability and old age to 2,201,000. In taking into ac count their families, the number of persons covered by social insurance in Czechoslovakia amounted to about 8,000,000. The total sum spent by institutions of social insurance in the year for their members amounted to 2,45o million crowns, their total capital to 14,54o million crowns. (V. P.; H. Ko.) Compulsory service in Czechoslovakia was introduced by a law of 1920 and was universal for all male citizens. A French mili tary mission was established in 1919, to remain for ten years, and to this mission a high standard of military efficiency can be attributed. Liability to service lasted from the age of 17 to 6o, but began normally at the age of 20. The president of the re public was the supreme head of the army under the constitution. The army was organized into 4 military areas and comprised 12 infantry divisions and a number of special brigades and troops. Particular attention was devoted to military education. The Czechoslovak army was regarded as one of the finest in Europe, both as regards training and equipment. The average strength of the army in 1937 was 10,0S9 officers and 153,356 other ranks, in addition to 12,647 gendarmerie. There were 6 regiments in the air force, having 566 aeroplanes. There was a small force of armed motor boats for river service on the Danube. (H. Ko.) Occupations.—According to the census of 1930, 34.64% of the population of Czechoslovakia were occupied in agriculture, 34.94% in industry, 7.43% in commerce, 5.53% in transportation and 4.86% in public service and the professions. These figures corn pare with 45.97%, 5.35%, and 3.71% respectively, according to the census of 1900. In Bohemia 24•06% were oc cupied in agriculture as against 56.82% in Slovakia, and 41.78% in industry as against 19•07% in Slovakia.

According to the data of 1936 the total area of the country comprised 5,855,00o hectares of arable land, 1,268,401 hectares of permanent meadows, 102,735 hectares of vegetable gardens, 25, 090 hectares of vineyards, 1,o66,000 hectares of pastures and hectares of forests.

Sugar beet, corn and high-grade barley for beer-brewing are cultivated in the low-lying areas, while in the more elevated regions the cultivation of potatoes, rye and oats predominates; the high lands, except those covered by forests, are used for grow ing fodder crops or for grazing.

The productivity of the soil varies considerably. Thus, in the west, where there is a high technical standard in agriculture, the productivity often exceeds the general maximum figures for Europe as a whole. But in the eastern areas (Slovakia and Car pathian Ruthenia) the productivity is much lower.

The distribution of cattle, which forms 75% of the total num ber of animals, exhibits similar variations. Productivity decreases from west to east, and while in the western regions there are 62 head of cattle per sq.km. a figure surpassed in Europe only by Denmark, Belgium and Holland, the number per sq.km. in the eastern areas is considerably less ; the average for the whole re public is 52 head per square kilometre.

The prominent position occupied by Czechoslovakia among the most progressive agricultural states is due to the high standard of Czechoslovak agriculture.

Agrarian Reform.—The Act of Parliament of April 16, 1919 gave the State the right to take over for partition estates in so far as they exceeded 15o hectares of arable land, or 25o hectares of land of any other category, indemnification being based on the average value between 1913-17. The total area affected by this Act was 926,817 hectares. By the end of 1924, 654,710 hectares had been taken over and redistributed. Of the agricultural land, 52% was allotted to small farmers and 25% to landless peasants. During 1925 a further 253,00o hectares were distributed.

Minerals and Mines.—The mineral wealth of Czechoslovakia was of great importance. The most important items are pit coal and lignite. The former has its chief centres in the Ostrava Karvinna coal-field, which is connected with the German and Polish coal-fields of Upper Silesia. In addition, there are the coal-fields of Kladno and Plzen. Other important coal-fields are near Briix, Komotau and Falkenau. The coal production amounted in 1937 to 16, 7 7 7,00o tons of hard coal and 17,895,0oo tons lig nite. Coal was an important article of export. Besides coal there are to be found iron, graphite, silver, copper, lead and rock salt in Czechoslovakia. Native iron ore was, however, inadequate for the native iron industry, and accordingly much had to be imported.

The abundance of excellent porcelain raw materials, particularly of kaolin, is of great importance both for home industry and for export purposes. The annual yield is about 400,00o tons, obtained chiefly from western Bohemia and southern Moravia. Systematic attention is being devoted to the exploitation of water-power re sources, together with a systematic process of electrification, and large steam-driven central power stations have been erected.

(V. B. ; H. Ko.) Industry.—It has already been pointed out that the agricul tural products of Czechoslovakia provide the raw materials for important agricultural industries. The most important of these is the old-established sugar industry, which is carried on in some 119 sugar factories. The beer-brewing industry had attained a world-wide reputation by reason of the excellent quality of its products. The agricultural industries include also flourishing spirit, malt and foodstuffs industries. Czechoslovakia's smoked meat products, especially hams, are of world-wide reputation. In there were 403 breweries producing 7,744,444 hectolitres of beer.

The abundance of coal and the presence of iron-ore provided the necessary conditions for the development of the metallurgical industries. The output of pig-iron in 1937 was 1,675,064 metric tons and that of raw steel 2,317,634 tons. The glass, porcelain and pottery industries also depended mainly upon the home sup ply of raw materials. All kinds of glass goods were produced ; in addition there were about 70,00o workers, who in their own homes made glass jewellery and beads which are known under the generic name of Gablonz ware. Crystal, ground and coloured Bohemian glass, all of high-grade quality, was largely exported to all parts of the world. The manufacture of porcelain was concentrated mainly in western Bohemia. The large forest areas provided the raw material for the flourishing timber, paper and cellulose in dustries. A great part of the output was exported.

Similarly highly developed were the textile industries which occupied in 193o more than 360,00o workers and the shoe industry of which the most famous establishment was the Bat'a works in Zlin. The textile industries comprised cotton, wool, flax and jute production. The leather industry was making great progress.

Communications and Transport.

In there were 69, 9o3km. of roads ifi Czechoslovakia; the number of automobiles amounted to 91,797 passenger cars, 29,616 trucks and 3,943 buses. There were 15,5o6km. of railway of which 12,385 were owned by the State. These railways formed a direct connection between the systems of Western and Eastern Europe and made Czechoslovakia an important centre of communication. This was as true of the highly developed air service. There were 13 lines operated in the national service and 21 in the international service.The peace treaties had internationalized the most important waterways. The Vltava and the Elbe (Labe) connected Bohemia with the North sea, and Czechoslovakia had the right to use cer tain wharves in the ports of Hamburg on the North sea and of Stettin on the Baltic sea. The Danube, where Bratislava was the chief port, connected Czechoslovakia with the Black sea. The total length of navigable waterways amounted to 418km., of which 2o6km. were represented by the Elbe and Vltava, and 172km. by the Danube. In 1935 the traffic on the Danube amounted to 627,326 tons, on the Vltava and Elbe to 1,9o5,110 tons.

The number of post offices amounted in

to that of the telegraphic offices to 4,784; in the same year there were telephone stations and 683,822mi. of telephone wire.Foreign Trade.—The large export and import trade of Czecho slovakia required it to build up a system of commercial treaties with foreign powers. The guiding principle of Czechoslovak trade policy was that of the most-favoured-nation clause. Upon this principle it constructed its whole system of agreements, which it supplemented by means of tariff conventions for customs purposes. A customs tariff of the former Austro-Hungarian em pire, drawn up in 1906, was adapted to the changed economic conditions by means of a system of co-efficients and became the basis of Czechoslovak customs policy as far as not replaced by any new items. The tariff agreements concluded with France, Italy, Austria, Poland, Greece, Spain, Belgium and Hungary led to a reduction of from 5o% upwards in the customs rates appli cable to more than two-thirds of the industrial products which formed the subject of trade.

Imports and exports amounted in millions of crowns to: Principal articles of import in 1937 were cottons, woollen goods, iron and steel, fruit and vegetables, fats and oils; principal arti cles of export were iron and steel, woollen goods, cotton goods, coal, glass-ware, sugar, cereals, timber and leather. Of the coun tries of origin the mast important were the following, arranged according to their importance in 1937: Germany, United States of America, Great Britain, France, Rumania, Austria, The Nether lands and Yugoslavia. Of the countries of destination the most important arranged in the same way were : Germany, United States of America, Great Britain, Austria, Rumania, Yugoslavia, The Netherlands, Switzerland and France. (J. D. ; H. Ko.) Czechoslovakia was a democratic republic. Legislative authority was exercised by parliament elected by universal, equal, secret and compulsory suffrage, based on the principle of proportional representation, and consisting of two chambers : a chamber of deputies of 30o members, elected for six years, and a senate of 15o members, elected for eight years. The franchise was open to all citizens without distinction of sex who were over 21 or 26 years respectively. Cabinet ministers, who did not need to be mem bers of parliament, were responsible to the chamber of deputies which by a vote of non-confidence could compel the resignation of the Government. A measure passed by the chamber of deputies became law despite an adverse decision of the senate if the cham ber of deputies adhered to the original decision by an absolute majority of all its members.

The president of the republic was elected in a joint session of the chambers for a period of seven years. He could be re-elected immediately for a second period ; for a third term, however, only after the expiration of seven years after the end of his second term. This restriction did not apply to President Masaryk. The president signed all laws enacted by parliament and had the right to return with his comments any measure enacted by it ; such a measure could become law only if repassed by an absolute majority of members of each of the two houses, or by three-fifths of all the members of the chamber of deputies.

The judiciary was separated from and independent of the ad ministration. The judges were appointed permanently and could not be recalled. The constitution guaranteed all citizens of the republic full equality before the law and equal civil and political rights, whatever be their race, language or religion, full personal freedom, inviolability of domestic rights and of the mails, free dom of the press, the right of free assembly and of association, and of the expression of opinion by word, writing or print, freedom of scientific research, of instruction, of conscience and religious creed. All religions were equal before the law. Wed lock, family and motherhood were placed under special protec tion; and special provisions of the constitution protected the rights of all minorities of language, religion or race, guaranteed to them the public maintenance of their schools, and forbad every manner of forcible denationalization. All these guarantees and rights were protected by the supreme administration court ; a constitutional court decided whether laws promulgated by parlia ment were in harmony with the character of the constitution.

Czechs and Slovaks in the Dual Monarchy.—During the century the problem of nationality in central Europe, and particularly in Austria-Hungary, became more and more acute as the process of national revival advanced, notably in the revolu tionary period of 1848. The Poles and Czechs awoke to the knowledge of historical state rights, and all nationalities felt the right to self-determination.

The leading German circles in Austria endeavoured to main tain their hegemony over the non-German nations in the empire and neglected the possibility of solving the nationality problem in the spirit of federalism with equal justice for all. The Czech nation, though possessed of a political consciousness, and with it also the other central European nations, entered the loth century subjected to a foreign regime, the domination of the Germans, the German-Austrians and the Magyars.

It was partly the wars of liberation in the Balkans, but espe cially the World War, which brought about a radical improvement in this state of affairs, bringing the political aspect of Europe more in accordance with its ethnographical aspect.

The Outbreak of War, 1914.

The Czech nation, which in consequence of the Thirty Years' War had been deprived of its political independence, had never abandoned the idea of recovering it, and in the i9th century did much to remove the far-reaching traces which the severe anti-reformation regime of the Habs burgs had left in its organism. Having successfully withstood the absolutist pressure of Germanization in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, while its Slovak kindred were slowly succumbing to the Magyarizing endeavours of the Hungarian state, it clearly saw that the outcome of the World War would have a decisive effect upon its existence. By its traditions, its sympathies and its whole political outlook the Czech nation was on the side of western European democracy and Slavonic Russia and Serbia against the central autocracies for whom the Czechs were called to fight. The opposition of the Czech nation to its political oppressors assumed the form of passive resistance, the passing over of Czech troops in great numbers to the Allies, and secret organizations, the pur pose of which was to prepare for the decisive moment. The brunt of the Czechoslovak revolutionary movement was, however, borne by the political exiles who, having escaped abroad at the begin ning of the World War, began to carry on in the Allied and neutral countries an extensive anti-Austrian action of a diplomatic, propagandist and military character, which aimed at achieving independence for the Czech and Slovak territories.

Organization Outside Austria-Hungary.

The necessity for systematic action abroad, and mainly in western Europe, was soon realized by Prof. Masaryk, the leader of the small Realist Party, who, as a member of parliament and of the Austro-Hun garian delegations, had for many years past—especially during the Bosnian annexationist crisis—been an opponent of reactionary Austria and especially of its provocative and dishonourable foreign policy. As early as the autumn of 1914 it was clear to him that the World War would not be decided on the Russian front, but in the west, and that it would last longer than was imagined by those who, guided by Slavonic sympathies, relied mainly on the strength of Russia. Being warned, on returning by way of Switzerland from an informative journey to Italy in Dec. 1914, that the Austrian police had orders to arrest him on his return, Masaryk decided to remain abroad and to organize the Czech campaign against Austria-Hungary, keeping, as far as possible, in continual touch with the underground activities of his friends at home to make the Czechoslovak question a subject of diplomatic negotiations on the part of the competent official circles of the Entente, which would effect its solution on international lines. For this purpose Masaryk proceeded to organize Czechoslovak settlers or residents abroad in order to make use of their resources and their influence in favour of his program. When the Czecho slovaks abroad were joined by a large number of Czechoslovak soldiers who crossed over to the Allied side, it was possible to consider the formation of special military units and a separate Czechoslovak army within the framework of the Allied armies. In all the Entente States there were spontaneous organizations of Czechs and Slovaks for the purpose of actively supporting the Allies in the struggle against the Central Powers. Czechs and Slovaks in the United States of America soon had an opportunity of doing important work, particularly in taking upon themselves the major part of the financial burden of the campaign.In the political public opinion of western Europe Austria-Hun gary was regarded as an element in the maintenance of European equilibrium. The Czechoslovak problem was looked upon as being an internal problem of the dual monarchy, which certain circles in the Entente were unwilling to alienate by formulating the final and extreme war aims, endeavouring rather to isolate Austria Hungary from Germany and thus weaken the latter, who was re garded as the sole culprit in bringing about the world catastrophe. Up to the moment when Austria-Hungary collapsed it was neces sary to fight against Austrophilism, which was powerful both in the neutral states as well as in the Allied countries and Russia. It was also necessary to struggle against the intensive Austrophile propaganda, by revealing the pseudo-constitutionalism and minor ity rule which were the true foundations of Austria-Hungary.

The Formation of Foreign Committees.

The year 1915 resulted in a mobilization of resources and the distribution of work for the Czechoslovak movement abroad, rather than in any positive successes. Up to the arrival of Dr. Benes (q.v.) in the autumn of 1915 the headquarters of this work were in Switzer land, but after his arrival Masaryk chose London as his seat of action, while Benes, as secretary of the Central Foreign Com mittee, proceeded to Paris with Stef anik, the Slovak scientist, who served as an aviator in the French army. Durich, a Czech agrarian deputy, was entrusted with the task of concentrating the work that had hitherto been accomplished in Russia by means of a unified Czech committee.Steps were very soon taken to form a Czechoslovak foreign committee for the purpose of carrying on a united struggle against Austria. On Nov. 14, 1915 a manifesto was issued, signed by Masaryk and Durich, by the leaders of the Czech colonies in the Entente states and notably also by the Czechs and Slovaks in America. This was the first official pronouncement by the Czechs abroad against Austria-Hungary, in favour of the Entente, and of the independence of the Czechoslovak state. At the begin ning of Jan. 1916 the Foreign Committee was transformed into a National Czech Council, the president of which was Masaryk, the vice-president Josef Durich, and the general secretary Dr. Benes. The Slovaks were represented on this Council by Gen. Stefanik.

The Czechoslovak Legions.

Considerable success and marked progress were achieved by the Czechoslovak movement in Jan. 1917, when the Allies in their reply to President Wilson's note on the peace conditions included the liberation of the Czecho slovaks from foreign rule among their chief war aims. In Russia a Czech brigade had in the meantime made further developments, and in June 1916 the tsar consented to the release of the Slav prisoners of war, but at the instigation of Stiirmer, supported by the tsaritsa, the consent was withdrawn at the beginning of August. In October an independent Czechoslovak division in the Russian army was sanctioned, but scarcely a month later this concession was also withdrawn. The Russian revolution of March 1917 did not bring any immediate advantage to the Czechoslovak movement there. It was not until the Czech regiments distin guished themselves at Zborov on July 2, 1917 that Kerensky was induced to allow additional troops to be recruited from among the Czech prisoners of war. Unfortunately the Russian army was already in a state of collapse and the Government of the March revolution was only short-lived. An agreement was con cluded between the French Government and the Czechoslovak National Council to transport Czech troops to France, and by a decree signed by President Poincare on Dec. 19, 1917 an inde pendent Czechoslovak army was established in France.In Russia, where in the meantime Masaryk had taken charge of the Czechoslovak movement, having left England in May 1917, the establishment of the first independent Czechoslovak body was reached during the interim Government in Oct. 1917.

Developments Within the Dual Monarchy.

In Bohemia in 1916 the Austrian persecution reached its culminating point. Under the military and police pressure no public political life was possible there. Conditions improved, however, after the death of Francis Joseph and the outbreak of the Russian revolution in March 1917. The May manifesto of the Czech authors and the proclamation of the Czech deputies on May 3o, at the first meet ing of the Reichsrat in Vienna, demanding the transformation of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy into a federative state with equal rights for the various nationalities, were the first signs of the coming spring. The representatives of the Czech Social Democrats at the Socialist Peace Congress at Stockholm in June 1917 ad vocated the right of self-determination and a demand for a sovereign Czechoslovak state within a Danubian federation.

The Czech Legions in Siberia.

The autumn Bolshevik revo lution complicated the situation of the recognized Czechoslovak units of the Russian army. Masaryk had already announced the Czechoslovak policy there as one of neutrality and non-interven tion in Russian affairs. On the principle of armed neutrality it was arranged with the Bolsheviks that the Czechoslovak troops should be transported via Vladivostok to France and the first detachment was dispatched at the beginning of November. In France, in Feb. 1918, the National Council had organized among the Czechoslovaks there a system of general conscription for the Czechoslovak legions. At the same time, the representatives of the Czechoslovak armies left France for Italy, where in April 1918 an agreement was reached between Orlando and Gen. Stefanik for organizing legions among the numerous Czecho slovak fugitives there on the Russian model.The clear relationship between the Czechoslovak command and the Bolsheviks, conditioned by the rejection of any plans aiming at intervention against the Bolsheviks, was complicated by the lack of loyalty shown by the Bolshevik Government, which during the transport of the Czechoslovak divisions demanded their dis armament. The incident at Chelyabinsk with the local Soviet in the second half of May 1918, led to the internment of the repre sentatives of the National Council at Moscow and the instruction issued by the Soviet authorities and Trotsky for the forcible dis armament of the Czechs. At the end of May hostilities began be tween the Czechoslovak troops and the Bolsheviks, during which the Czechoslovaks occupied the whole of the railway line as far as Irkutsk and gained possession of the Baikal and Chita railway, 5,000mi. in length.

Masaryk, who in March 1918 left Russia and arrived in May in America, opposed all idea of aimed intervention in Russian affairs, but when the Bolsheviks provoked an armed conflict with the Czechoslovak troops in Siberia, he asked America and the rest of the Allies for military and material help for the Siberian legions, who were suffering especially from lack of equipment. The Allied Governments decided at Washington, notably by an American-Japanese agreement, to grant the military and material assistance asked for (Aug. 3). The military help promised by the Entente was not forthcoming, with the exception of a small Japa nese contingent, but abundant quantities of supplies and equip ment were given. The victory of the Czechoslovak troops on the Volga and in Siberia caused a sensation in the Allied states, so that the Czech success had a considerable moral significance and denoted the strengthening of the Czech cause. What made the Czech achievement particularly valuable was that it had prevented the Soviet Government, and thus also Germany, from obtaining the keenly desired contact with the Siberian supplies of raw materials and foodstuffs, and also that the vast numbers of Ger man prisoners of war in the Siberian camps could not be used for strengthening the German army. Lloyd George (Sept. 11, 1918) thanked the National Council in a telegram for the in estimable services rendered by the legions to the Allies.

Recognition by the Powers.

Great Britain had previously, in a pronouncement of Lord Robert (Viscount) Cecil on May 22, 1918, officially recognized the right of the Czechoslovak na tion to complete independence. When on May 29, 1918 the Government of the United States approved the anti-Austrian resolution passed by the Congress of Oppressed Nations in Rome, which had been organized in April of that year by Dr. Benes on the initiative of Professor Denis, the War Council at Versailles associated itself with this American proclamation, while the prime ministers of France, Britain and Italy, and indeed of all the Allied nations, declared their sympathies with the Czechoslovak and Yugoslav aims for liberation. At the same time, the British Government announced its willingness to recognize the National Council as the leading body of the Czechoslovak movement and also of the army that was fighting on the side of the Entente. The first country to grant actual recognition in this sense was France (June 29, 1918). On June 3o President Poincare, with the representatives of the French cabinet, handed over the colours to the 21st Czechoslovak regiment at Darney, and on the follow ing day the British Government expressed its agreement with the speech made by President Poincare on this occasion.About the same time a second, supplementary agreement was reached with Italy concerning a Czechoslovak army within the framework of the Italian army, and the Government of the United States in its pronouncement identified itself with the complete liberation of all branches of the Slav race under Ger man and Austrian domination. About 50,000 Czechs and Slovaks then offered themselves as volunteers for the army of the United States, apart from those in the Canadian army and in France. By a declaration on Aug. 9 the Government of Great Britain recognized the Czechoslovaks as an Allied nation, the three Czechoslovak armies as a single Allied army carrying on regular warfare against Austria-Hungary and Germany, and the National Council as the supreme body controlling national interests. On Sept. 3, 1918 the British Government recognized the future Czechoslovak Government upon the basis of the National Council and negotiated a convention with the National Council concerning an army and diplomatic relationships on the basis of the analogous international position of Serbia and Belgium. On the same day a similar recognition was obtained from the United States Gov ernment, and on Sept. 9, 1918 the recognition of the Japanese Government in the same sense was obtained.

The success of this intensive diplomatic struggle for inde pendence, carried on partly from Paris by the headquarters of the National Council, partly by Masaryk at Washington, and achieved to a considerable extent through the merits of the Czechoslovak legions, was promoted in no small degree by the resolute action of the Czech political leaders in Austria-Hungary itself. Important in this respect are the manifestos of the Czech deputies of Jan. 6, 1918, the vow made by representatives of all sections of the nation on April 13, 1918 that the struggle for Czech independence should not cease until the final victory, and the May celebrations of the National theatre at Prague, which were attended by representatives of other oppressed nations in Austria, especially the Yugoslays, Poles and Italians—all this enhanced the movement abroad, which in the autumn of 1918 was reaching its final goal.

Declaration of Independence.

Finally, on Oct. 14 Dr. Benes notified the Entente states of the establishment of an interim Czechoslovak Government in Paris in accordance with the decision of the president of the National Council on Sept. 26, and Dr. Benei as minister for foreign affairs was appointed the first Czechoslovak minister to the Entente states. This interim Czechoslovak Government was recognized by the French Govern ment on Oct. 15, and by the Italian Government on Oct. 24, while on Oct. 18, 1918 the interim Government itself proclaimed the independence of the Czechoslovak nation by a declaration dated at Washington. On the same day President Wilson re jected the Austro-Hungarian peace offer of Oct. 7 on the ground that since the issue of his Fourteen Points (q.v.) on Jan. 8, 1918 the Government of the United States had recognized a state of war between the Czechoslovaks and Austria-Hungary, and inti mated to the Austrian Government that it should apply to the National Council which had already been recognized as the de facto Government of the Czechoslovak nation.In Bohemia the socialist parties, especially in the rural districts, had attempted to proclaim a republic on Oct. 14. Wilson's reply, rejecting a peace offer by the Emperor Charles, was published in Austria-Hungary on Oct. 21, and within a week, notably through the collapse of the army, all the conditions were fur nished for the capitulation of Austria-Hungary, which took place in the night between Oct. 27 and 28. On Oct. 24 the Czech deputies had already obtained permission from the emperor to proceed to Geneva for the purpose of conferring with Benes there. The National Committee at Prague, however, did not await their arrival but drew its own conclusions from the Austrian capitulation, and on Oct. 28, by its first law, proclaimed the independence of the Czechoslovak state, taking into its hands the administration of the Czech territories without encountering any considerable opposition from the army or from the author ities. Two days later, on Oct. 30, by a manifesto of the Slovak National Council at Turcansk' Sv. Martin, Slovakia pronounced itself in favour of Czechoslovak unity.

Oct. 28 remains the symbol of the national liberation from the centuries of Habsburg bondage, although the actual transforma tion was carried out early in the subsequent days by an agreement between the Government of the Czechoslovak state in Paris and the National Committee, which took over all the commitments of the former. The conferences at Geneva also gave the renewed state its definite form of a democratic republic. On Nov. 13 the National Committee issued an interim constitution and a day later there was a meeting of the Czechoslovak National Assembly con stituted in accordance with the proportional numerical strength of the individual political parties, containing 256 (later 27o) members, of which 44 were Slovaks. There were no Germans among them, the German representatives having refused partici pation. At this first meeting of the National Assembly Masaryk was unanimously elected the first president of the Czechoslovak republic, and on the basis of the interim constitution the National Assembly elected its first Government. The prime minister was Itramai, the foreign minister Benes, and the minister for war Gen. Stefanik. On Dec. 21 the president returned to Prague, and his inaugural message, pronounced in the National Assembly on the following day and containing a concise survey of the Czechoslovak movement for independence abroad and a plan for the further consolidation of the republic, concludes the revolutionary period and begins the constructive period' of the state. The Peace Conference had yet to define only a few details of the relations of Czechoslovakia to its neighbours and to the other members of the comity of nations. (T. G. M.) 1918-1935 The Kramar` Ministry.—The first ("Revolutionary") Czecho slovak ministry consisted of four Agrarians, three Czechoslovak (national) Socialists, three Social Democrats, three National Dem ocrats, one People's Party and one Slovak member. Benes and tefanik were non-party. During its eight months of office the Government had to maintain the integrity of the national terri tory, to keep the administration working and to defend the in terests of the country at the Peace Conference. Further, it had to face the problems arising out of the economic difficulties of the period, especially as regards provisioning, and out of the international situation of the new state. It dealt with all these tasks successfully.

First, it put down the attempted insurrections in the German speaking districts of Bohemia and Moravia, which had attempted to unite with Austria. In Slovakia there were grave difficulties owing to the departure of most of the Hungarian bureaucrats, the hostility of the Magyar and Magyarophile elements of the population and to the fact that the frontiers were not yet regu lated. On Feb. I, 1919 the Slovak Government was formally in stalled at Bratislava. After the Communist Party came to power in Hungary there were further grave complications. The Hun garian communist troops invaded Slovakia, which Czech troops were occupying. They were repelled with the help of the Allies, who, as a result of this episode, fixed a of demar cation which was maintained without great change when the frontier was finally traced on June i 2, 1919. Similarly in Teschen (Tesin) the situation was grave owing to the conflict with the Poles, who had occupied part of this territory. The Czech Govern ment in its turn occupied Teschen and there were conflicts at tended by bloodshed. The Peace Conference had to intervene. An armistice was concluded on Feb. 19 and the dispute was referred to diplomatic negotiations (see TESCHEN).

This Government carried through much important financial and social legislation. It effected the financial and economic separation of Czechoslovakia from Austria (notably by Rasin's legislative measures of Feb. 1919), secured the food supply, tem porarily threatened by the effects of the World War, through pur chases from abroad, and laid the foundations of political and eco nomic democracy. The chief measures included the new com munal suffrage, the eight-hour day, and the commencement of the land reform; measures which both realized the ideals held by the nation and averted the danger of an extremist social move ment.

The First Tusar

municipal elections of June 15, 1919 clearly showed that the composition of the Government and of the National Assembly did not correspond with the real numerical importance of the different parties. The cabinet accordingly resigned, and on July 8, 1919 President Masaryk ap pointed a second cabinet under Tusar, a leader of the Social Democrats. The new Government represented a coalition of the parties which had been most successful in the elections. Besides Tusar (minister president) it included three other Social Demo crats, four Czechoslovak Socialists, four Agrarians and two Slovaks, Benes retaining his portfolio.During the period of office of Tusar's cabinet Czechoslovakia consolidated her international situation. The interests of the country were successfully defended at the Peace Conference. On Sept. i o, 1919 the Treaty of St. Germain with Austria had been signed and on the same day the so-called "little treaty" of St. Germain, which guaranteed the rights of minorities in Czecho slovakia. Under the guidance of Benes commercial relations were developed between Czechoslovakia and her neighbours. The re lations between Austria and Czechoslovakia soon became friendly and the ground was prepared for future political agreements.

In its financial and social policy this Government continued the work of its predecessor. A number of foreign loans were raised to meet urgent requirements, a fiscal reform was carried through and an extraordinary levy on capital imposed. The chief social measures were the Works Councils Act and the act establishing profit-sharing in the mining industry. The most important task of Tusar's cabinet was the elaboration of the constitution. In view of the attitude adopted by most of the German population it was resolved that this should be voted by the revolutionary National Assembly rather than by a nationally elected parliament. A special commission elaborated its general principles and its text. Several points—the question of a second chamber, of the separation of church and state, of the system of military organ ization, and especially of the incorporation of the language laws in the constitution—gave rise to vehement debate before the constitution was finally adopted on Feb. 29, 192o.

The Second Tusar general elections were held in April 1920. The result showed that the Czechoslovak Socialists and Agrarians commanded a majority in the country. Tusar therefore formed a second cabinet, in which Benes again held the portfolio of foreign affairs.

Assembling in May, the new National Assembly, in joint ses sion of both chambers, re-elected M. Masaryk as president of the republic by 284 votes out of 41i. On June 1 the new cabinet read its program, which envisaged an advanced democratic and social policy. Appealing to the German "representatives, Tusar declared that if the two nations had hitherto failed to co-operate, this was not due to the fault or the wishes of the Czechoslovak majority but to the attitude of the Germans themselves. The reply of the German bourgeois parties, however, which was re peated in a modified form by the German Socialists, showed their intention of persisting in their negative policy towards the re public. The German problem remained as far as ever from a solution.

A split in the Social Democratic Party, with the left wing join ing the Third International, forced the resignation of the cabi net in Sept. 1920. It was replaced by a cabinet under Cern, made up largely of high public officials. The new situation paved the way for a coalition of five Czechoslovak parties, the Social Democrats, the Czechoslovak Socialists, the National Democrats, the Agrarians and the People's Party. These five parties formed a Council of Five, the so-called Petka, to insure contact and or ganized collaboration between the Government and the majority. This paved the way for the formation of a new parliamentary Government.

The Benei Cabinet.—As soon as the Social Democrat Party had reconsolidated itself after its break with the Communists, it expressed its readiness to re-enter the Government. The cabinet of officials was accordingly replaced by a new parliamentary Government in the shape of the Benei cabinet, which was con structed on Sept. 27, 1921. The Government majority included the five great Czechoslovak parties, and also enjoyed the support of the minor Czechoslovak parliamentary groups, so that it could thus command a secure majority of i8o votes in the chamber against the 78 of the national minorities and the 25 Communists. Benes became premier, his cabinet included three Social Dem ocrats, three Agrarians, two Czechoslovak Socialists and one Na tional Democrat. The premier, who also acted as foreign minister, and the ministers of finance, the interior and Slovakia, were non party men. Benei' appointment was in general well received; the German press and deputies regarded it as a hopeful symptom.

The

Government remained in office from Sept. 26, 1921 to Oct. 7, 1922. The foreign situation during this year was par ticularly full of incident, including the second attempt at res toration (Oct. 20, 1921) of the ex-King Charles in Hungary, as a result of which Czechoslovakia commenced mobilization, the conclusion of a political convention with Poland (Nov. 6, 1921), which, however, remained unratified (see LITTLE ENTENTE), of a treaty of guarantee and arbitration concluded on Dec. 16, 1921 at Lamy (Lana) with Austria, the Conference of Genoa in March and April 1922, the negotiations for the expansion and strengthen ing of the Little Entente and the difficulties arising out of the fresh financial collapse in Austria in 1922. These questions pre occupied the attention of the Government somewhat to the ex clusion of internal affairs. The internal economic situation was difficult and the cost of living high, both for general reasons and owing to the sudden rise of the Czech crown. There were serious labour troubles, such as the miners' strike of Feb. 1922 and the strike in the metal industry in May 1922.The history of the Benes cabinet so conclusively proved the feasibility of a concentration cabinet that when it resigned, on Oct. 5, 1922, the system was maintained on an even broader basis. The new ministry was formed on Oct. 7, its head being Svehla, leader of the Agrarian Party and one of the most in fluential members of the Petka.

The Svehla

new cabinet consisted of five Agrarians (including the premier), five Social Democrats, three Czechoslovak Socialists (including Benes, who retained the port folio of foreign affairs), two members of the People's Party and two National Democrats (including Rasin, who again took the ministry of finance). Its program was presented on Oct. 24 in the form of three exposés by Svehla, Benes and Rasin re spectively. This Government was successful in decreasing the coal tax and the tax on property, to the benefit of industry and agriculture, and it was also able to maintain the stability of the exchange and to carry through the important measure of social insurance of both workmen and independent persons. It failed, however, to solve by inter-party agreement the question of agri cultural tariffs, a point on which Agrarian interests, and especially the Agrarian Party, laid the greatest stress. In June 1925 a temporary solution was reached by the introduction of the so called sliding customs tariff ; yet this expedient, while represent ing the maximum of concessions which the Socialists were willing to grant, was not permanently satisfactory to the Agrarians. The result was a permanent discord, which was even increased by the events of , July 1925.The chamber met on Sept. 18 to discuss the budget estimates, which, for the first time, provided for a surplus of revenue. The budget was passed (the Germans abstaining}, but the chamber was unable to carry through a bill which introduced a slight amendment in the electoral system (dividing Prague into two constituencies). It was obliged to abandon the rest of its pro gram. The two chambers were dissolved on Oct. 16, and new elections for both fixed for Nov. 15.

Second Svehla Cabinet and Second Cabinet of Officials. —The results of the elections brought about a considerable re arrangement of the strength of the parties of the coalition. The People's Party gained greatly, the Agrarians to a lesser extent, the Social Democrats were weakened, mainly because Communist candidates split the labour vote. The National Democratic Party was also weakened. In general, however, the five coalition parties did not lose their ability for government, especially as they were joined by the Traders' Party as a sixth member, which almost made up for the losses which they had sustained.

On Dec. 9 Svehla's second cabinet was formed, its constitution being as follows: Agrarians four, Social Democrats three, Czecho slovak Socialists three, Czechoslovak People's Party three, Traders' Party one, National Democrats one. Two places were occupied by non-party ministers, one of these being Englis, the minister of finance. The position of the socialist parties in this Government was much weaker, and their collaboration with the non-socialists more difficult. After the Government had passed the decree of Feb. 1926 for the enforcement of the Minorities law, the growing tension led to its resignation.

It was succeeded by a fresh Government of officials under Dr. Jan Cerny, only Benes, Englis and Kallay being included from the former Government. The Czechoslovak bourgeois parties, the Czechoslovak-German Farmers' Party and the Christian Socialists formed the Government coalition, all socialist parties being in the opposition. The customs Tariff bill was approved, after a heated struggle, on June 12, 1926, being followed by the State Employ ment bill, the Congrua bill (ministerial salaries) and the "refund ing bills" (sugar tax and increase of the tax on alcohol).

(K. SE. ; H. Ko.) The Development after 1927.—On Oct. 12, 1926 a new par liamentary Government was appointed, which for the first time was based on the collaboration of Czech and German bourgeois parties. Two Germans, representing the German Catholic Party and the German Agrarians, participated in the cabinet, the head of which was again Svehla. The adherence of the Germans, who from 1926 until 1938 participated actively in the administration of the country, seemed to bring the solution of the German minor ity problem nearer. The Slovak Peasant Party which was autono mist and clerical in its outlook, also joined the Government in Jan. 1927 and as one of its representatives Josef Tiso entered the cabinet. On July 1, 1927 the republic was divided for administra tive purposes into four parts, Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, Slovakia, Carpathian Ruthenia. This division allowed the granting of larger regional autonomy, thus trying to fulfil the wishes of the Slovak autonomists.

The good relations with the Slovak Popular Party were, how ever, disturbed, when in 1929 one of its leaders, Dr. Tuka, was tried for separatist agitation and treasonable relations with Hun gary, and was condemned to fifteen years of imprisonment. New elections on Oct. 31, 1929, changed the composition of the parlia ment, and on Dec. 8, 1929, a new cabinet was appointed under Udrial, a Czech Agrarian as prime minister, and with the partici pation of Czech and German bourgeois and socialist parties. The number of German representatives in the cabinet remained at two, a Social Democrat and an Agrarian, but was later raised to three by the inclusion of a German clerical. President Masaryk had been re-elected on May 27, 1927 for a second period of seven years. The Government of Mr. Udrial was followed by a cabinet under Malypetr, a Czech Agrarian himself, and the composition of the cabinet did not fundamentally differ from the preceding one. It had been appointed on Oct. 3o, 1932, and was re-appointed with a somewhat changed personnel on Feb. 14, New elections were held on May 19, 1935. These elections were held largely in the shadow of the changed international situa tion. The problem of the German minority in Czechoslovakia was transformed from a problem of internal policy which was well on its way toward solution, into a problem of international policy and was made subservient to the German attempt at expansion and domination over central Europe.

The New

remarkable stability of Czechoslo vak democracy expressed itself also in the unbroken continuity of the leadership of the republic. The first president, Thomas G. Masaryk, the president liberator, remained the head of the state he had done so much to create and to shape, from the fall of 1918 until Dec. 1935. When he had to resign on account of his ad vanced age (he was then in his 86th year) he was succeeded by Dr. Eduard Benes, who was elected by a large majority on Dec. 18, for the presidential term of seven years. Dr. Benes had been the closest disciple and collaborator of Masaryk for more than twenty years, and had since 1918 been minister of foreign affairs of Czechoslovakia. As a statesman, as a sociologist and as a student of ethics, Benes followed closely the line of his prede cessor. Masaryk, although in failing health, lived on for two more years; his death on Sept. united the whole nation in an impressive demonstration for the great humanitarian democrat. On Nov. 5, Dr. Milan Hodia, a member of the Agrarian Party and a Slovak, became prime minister. Dr. Kamil Krofta, a distinguished historian, took over the foreign office on March 1, 1936. Both continued in office until the September crisis of The Rise of National Socialism.—The accession to power of the National Socialist Party in Germany, the growing strength of Nazi Germany in international relations, the spread of fascist in fluence and of a chauvinistic and exaggerated nationalism through out central Europe, the weakening of the League of Nations and of the ideals for which it stood, all that was reflected in the atti tude of the German minority in Czechoslovakia. Since 1926 Ger man ministers had participated in Czechoslovak cabinets. This rapprochement between the two races coincided with a general improvement created by the Locarno Pact. But the German mi nority continued to feel themselves treated as second-rate citizens. Undoubtedly some of their grievances were legitimate. Czech in fluence and numbers were constantly growing in predominantly German districts. The Czech language was given a prominent place, Czech officials and police were employed in German cities and districts. In economic enterprises, financed by the Govern ment, Czech employers and workers were given preference in Ger man territory. But viewed in the light of the position of minorities generally throughout central and south-eastern Europe there is no doubt that the situation of the German minority in Czechoslo vakia was relatively good, and that the democratic liberties were shared equally by the Germans with all the other nationalities of Czechoslovakia. The discontent of the Germans was aggravated by the general economic crisis which hit the predominantly indus trial and less fertile parts of Czechoslovakia, inhabited by the Ger mans, much more heavily than the more agrarian districts.The Czechoslovak Government dissolved on Oct. 4, the two extremist German nationalistic parties, the Nationalists and the National Socialists. A few days later a young teacher of gym nastics, Konrad Henlein, formed a new party, the Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront, later called the Sudetendeutsche Partei, or Sudetic German Party (the Sudeten is the name for the mountains sep arating Bohemia from Germany). The new party professed loy alty to the Czechoslovak state, but imitated the German National Socialist Party in its authoritarian totalitarianism, in its racial in terpretation of history and in its fight against liberalism and so cialism. This party became at the parliamentary elections of May the strongest German party, gaining about two-thirds of the German vote. The other three German parties, the Agrarian Party, the Clerical Christian Social Party and the Social Demo crats, co-operated with the Government and entered a coalition cabinet with the Czech parties. The Sudeten Party demanded the autonomy of the Sudetenland and above all a complete change in Czechoslovakia's foreign policy and her re-orientation into the German orbit. These demands of the Sudeten Party were sup ported by the German press in the Reich which launched from time to time vehement attacks against Czechoslovakia.

International Policy.

By her geographic position Czecho slovakia was the pivotal point in the struggle for a balance of power in Europe and in the efforts to maintain democracy in cen tral Europe. This strategic position of Czechoslovakia grew in im portance, as Germany resumed her expansion eastward in an effort to establish her control over the Danubian basin, to strengthen her potentiel de guerre by the economic resources of central and south-eastern Europe and by helping fascism to become the dom inating political philosophy in all the countries which would fall under her influence. Against this drive for the expansion of Ger many's strategic and economic power Czechoslovakia relied upon the League of Nations to which she always had faithfully adhered, and made her relations with the other members of the Little En tente, Yugoslavia and Rumania, closer by the pact of Feb. 16, The alliance with France, which had been a cornerstone of Czechoslovak policy since her foundation, became more intimate and was reaffirmed in a number of solemn declarations. Under the influence of France Czechoslovakia altered also her attitude toward the Soviet Union, being one of the last states to extend recognition. After France had concluded a defensive pact of mutual assistance with the Soviets, Czechoslovakia followed suit on May 16, At the same time the Czech Government concentrated its atten tion on strengthening its army which was raised to a very high standard and was in training, equipment and efficiency equal to the best armies of Europe. A line of most modern fortifications, a second "Maginot" line, was built along the German frontier to protect the country against any surprise attack. The armament works of Czechoslovakia, especially the famous Skoda Works in Pilsen, were world renowned. In addition to her reliance upon world democracy, upon her friends and upon her army, Czecho slovakia pursued an active policy for improving her relations with her neighbours. The Czechs tried to promote the ideal of an economic and a diplomatic co-operation between the states of central Europe for the maintenance of their independence and their traditions. The relations with Austria became more cordial, and better relations with Hungary were established than there had existed since the end of the World War. Definite prospects of a peaceful consolidation and development of the central European situation appeared toward the end of Efforts at Czech-German Conciliation.—To lessen the pre vailing tension the Government of Dr. Hodia started negotiations with the three German parties who were co-operating with the Government. Only three major parties remained outside the coali tion, the Sudeten German Party, the Communist Party and the Slovak People's Party, the latter a reactionary clerical party with fascist tendencies under the leadership of Father Andreus Hlinka. On Feb. 18, 1937 an agreement was concluded between the Gov ernment and the three German parties within, whereby the Ger mans were promised their just share in public economic enter prises, their due representation in civil service and certain im provements in the thorny question of the inequality of the Czech and German languages. Certain steps were taken toward satisfying the demands of the Slovaks and of the Carpatho-Russians for au tonomy. But all these measures were carried out only slowly and did not keep pace with the rapidly changing international situation where Germany was striding fast to attain her ends.

After the Annexation of Austria.

Chancellor Hitler in his speech on Feb. 20, 1938 had declared that the German minority in Czechoslovakia as well as the Germans in Austria should feel confident of the Reich's support. Nine days later Field Marshal Goring warned that "since the Fuehrer made the proud statement that we would no longer tolerate that ten million of our German brothers across the frontier should be oppressed," the soldiers of the German air force knew that they must "stand for this word of the Fuehrer until the end." Ten days later German aeroplanes and troops moved into Austria and the country was annexed. This fact rendered the situation of Czechoslovakia even more precari ous. It aroused in the German minority the definite expectation that within a brief time Chancellor Hitler would "liberate" them. In this mood many Germans joined the Nazi Party. Of the three German parties co-operating with the Government, the Agrarians and the Christian Social Party dissolved and joined the Sudeten Party, the German Social Democrats also withdrew from the cabi net. The demand of the Sudeten Germans for autonomy was now taken up by the Hungarian and Polish minorities and by the Slo vak People's Party. The Czech Government promised to grant further concessions to the German minority, but the eight de mands laid down by Henlein in a speech at Carlsbad on April 24, proved unacceptable, because they included not only a complete autonomy for the Germans, but an insistence upon the acceptance of the totalitarian Nazi philosophy, incompatible with the demo cratic character of Czechoslovakia. The Sudeten German Party, which on May 13 created its own uniformed storm troopers, be came more and more insistent, frequent incidents resulted, govern mental authority in the Sudeten districts was undermined, the fol lowers of Henlein terrorized the German Socialists and Democrats. A general feeling prevailed that on May 21 German troops would move into the Sudetenland to support a Sudeten revolt. A quick mobilization of part of the Czech army, carried through with greatest preciseness and efficiency, forestalled, at least for the time being, any such move. But the German Government ordered on May 29 a sharp increase in the German army which was raised during the early summer to the strength of 1,500,00o men under arms, and concentrated about 5oo.000 conscripted labour upon the rapid construction of impregnable fortifications on Germany's western front.Meanwhile negotiations continued between the Czech Govern ment and the different minorities, especially the Sudeten Germans, about a general revision of the status of the minorities in Czecho slovakia. These negotiations were hindered by the violent cam paign of abuse and hatred carried on by the German press and radio against Czechoslovakia. Under these circumstances and with Germany's threat of war against Czechoslovakia more and more imminent, the British Government sent, at the end of July, Lord Runciman to mediate between the Czechs and the Sudeten Ger mans. The Czech Government submitted proposals for far-reach ing concessions to the Sudeten Germans, embodying most of their demands for self-government. But the Sudeten Germans refused, under the pretext of minor incidents, to negotiate. At the same time Chancellor Hitler in his speeches during the month of Sep tember sounded a more and more warlike note. With the danger of armed conflict rapidly growing the British and French Govern ments started negotiations with Germany. As the result of these negotiations they forced Czechoslovakia to accept the German de mands for a dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. The Czech Gov ernment had not even been consulted during these negotiations. Finding itself forsaken by its allies, it had no other choice than to become resigned to the establishment of German undisputed hegemony in central Europe at the expense of Czechoslovakia, but also at the expense of democracy, of the prestige and position of Great Britain and France, and of the League of Nations.

After the Pact. of Munich.

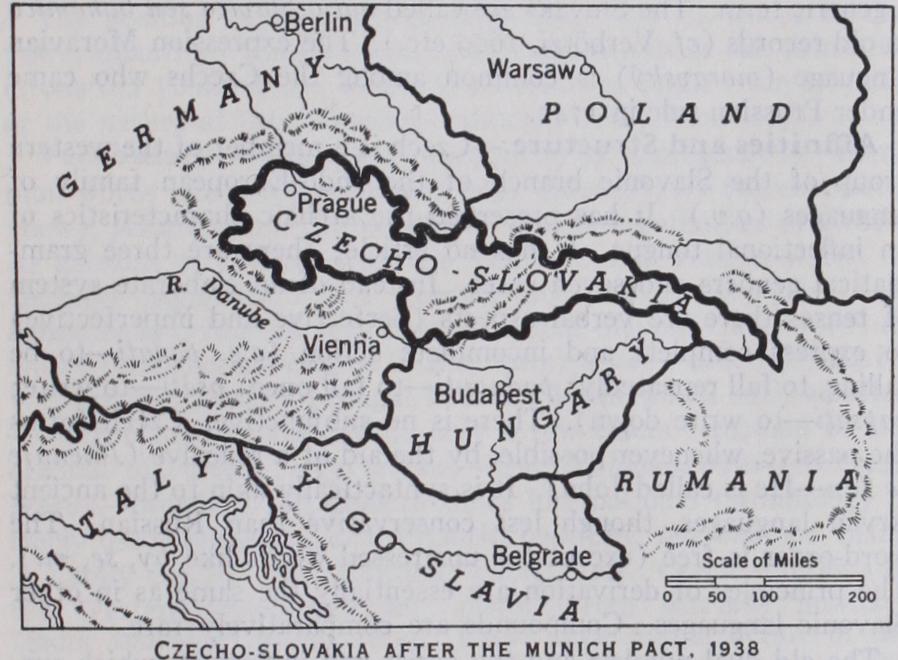

The accord of Munich of Sept. 30, 1938 sealed the fate of Czechoslovakia. On September 22 the Government of Dr. Hodia had resigned and General Jan Syrovy, the inspector general of the army, had formed a new cabinet. This cabinet was now faced with the task of carrying through the ces sion of all the territory inhabited, according to the census of 1910, by a German majority, to Germany, and to face similar claims on the part of Poland and Hungary. The Polish claims were fully granted, those of Hungary, after long negotiations, were settled on November 2 by a judgment of the German and Italian foreign ministers who acted as arbiters. Meanwhile, on October 5, Dr. Benes resigned as president of the republic, a second cabinet of General Syrovy's was formed with Dr. Frantisek Chvalkovsky as foreign minister, who was well known for his sympathetic attitude toward Germany and Italy. This cabinet carried through the dif ficult transition from a democratic Czechoslovakia, relying upon the League of Nations and the western democracies, to a new fed erative state Czecho-Slovakia, with fascist tendencies and entering entirely the political, economic, strategic and cultural orbit of Germany. Thus the First Czechoslovak Republic created by Masaryk was followed by a Second Republic thy; tendencies and ways of life of which differed fundamentally from its predecessor.

The Second Czecho-Slovak Republic.

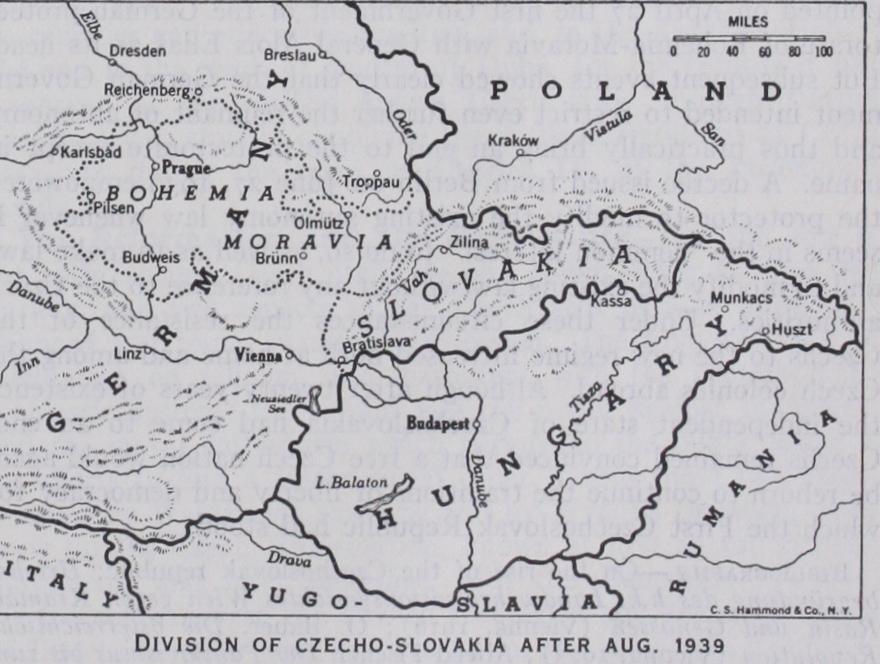

Czechoslovakia lost 28,68o sq.km. to Germany, 11,830 to Hungary, and 1,086 to Po land. Her area after the Pact amounted to 98,912 square kilo metres. Of her population she lost 3,576,719 to Germany, to Hungary and 230,282 to Poland. Among this population lost there were about 1,202,000 of Czech and Slovak nationality who now formed minorities in Germany, Hungary and Poland. The total population of the new Czecho-Slovakia amounted to 9,807,096 or two-thirds of the original population.The new Czecho-Slovakia was a federal state consisting of Bo hemia and Moravia with 49,362 sq.km., Slovakia 38,456 and Ruthenia 11,094. Bohemia and Moravia contained more than two thirds of the present population, namely 6,804,876. The three federated Slav nationalities, the Czechs (6,453,857), the Slovaks (2,055,802) and the Ruthenes (512,289), formed together 93.4% of the whole population. The remaining national minorities, the Germans, Hungarians, Jews and Poles, were numerically in significant.

The relations between the Czechs and the Slovaks were regu lated in a way similar to that existing in the Dual Monarchy of the Habsburgs after 1867. Although numerically much inferior, the Slovaks set the pace of the development of the Second Republic and led the distinct swing to right-wing fascism which became characteristic of the Second Republic. The Slovak Government under Monsignor Josef Tiso, the successor of Father Hlinka who had died in Aug. 1938, established a one-party rule, created a fascist militia, and started a violent anti-Semitic campaign copy ing the German example. The development in the western part of the country went in the same direction although much slower and under preservation of certain features of an "authoritarian" de mocracy. The Czechs knew that they depended for their survival entirely upon the goodwill of Nazi Germany. They had therefore to adapt their whole economic, political and cultural life to this new situation. The Czech parties were dissolved, the Communist Party outlawed, anti-Semitism grew rapidly under German propa ganda. The democratic period of Czechoslovakia, the memory of Masaryk, the personality of Benes, were violently attacked by the new forces which had come to the fore among the Czechs. The Czech Conservative parties formed a party of National Unity which became the majority party in the Czech parliament, op posed by a Czech labour party which tried to maintain, as far as it was possible in the new situation, certain traditions of the demo cratic past.

The Czecho-Slovak parliament accepted on Nov. 22, 1938 the autonomy statute for Slovakia. On Nov. 3o it elected Dr. Emil Hacha, the president of the supreme administrative court, presi dent of the new republic. A new cabinet was appointed under Rudolf Beran, who had been for many years an advocate of a Germanophile policy. The new Government sanctioned the build ing of a German corridor across Czecho-Slovakia, to connect Ger man Silesia with Vienna. This corridor was to be regarded as part of the German political and customs territory, and to be under German sovereignty. In addition to this road a canal was to be built by Germany across Czecho-Slovakia, connecting the Danube with the Oder, and thus to bring the countries of central and south eastern Europe into the German economic and political orbit.

German influence made itself also heavily felt in Carpatho Ruthenia which was, under the new premier, Monsignor August Volosin, transformed into the spear-head for the "liberation" of all Ukrainians, living in Poland and the Soviet Union, by Germany.