International Cricket

INTERNATIONAL CRICKET Europe.-Wherever Englishmen, and especially English sol diers and sailors or missionaries, have gone, they have taken cricket with them. But for the outbreak of the Revolution it would have been played in Paris in 1789 under the auspices of the British Ambassador; the Light Division enjoyed it at Lisbon before the battle of Busaco ; some of the "secretariat" indulged in it on the Prater during the congress of Vienna ; the game had been played in Italy by 1828, in Corfu during the British Pro tectorate (1815-63), in Odessa in 1881, whilst a cricket club was formed in Geneva as early as 185o and in Christiania by 1866. Of European countries to-day the Dutch and the Danes are the keenest and most proficient.

India.-There

was a cricket club in Calcutta before the end of the 18th century, and fostered by the enthusiasm of the Army and the encouragement of such men as Lord Harris, when gover nor of Bombay, the natives rapidly mastered the game; the tri angular tournament between Europeans, Parsees and Hindus dates from 1907, the Mohammedans joining in 1912. The first "test" match with England was played in 1932 in England, when the Indians lost. In India, in 5933-4, the M.C.C. won two matches and drew one. Of test matches played, up to 1935, between Eng land and the West Indies, England won 7, West Indies 3, and 4 were drawn; West Indies winning the rubber against the M.C.C. tourists in 1934-35.

America.-Cricket

has been played all over the American continent, and a match at New York took place as early as 1751. The first team of professional cricketers that ever left England toured the U.S.A. and Canada in 1859, an example that has been enjoyably followed by many subsequent teams, including Kent County in 1904. The compliment has been returned by the Phil adelphians, Pennsylvania and Haverford universities. Though the U.S.A. has produced some fine cricketers, notably the broth ers Newhall in the '7os, J. A. Lester, who captained the Philadel phians in 1904, H. V. Hordern, a first-rate googly bowler, and above all, J. B. King, in 1904, one of the very best bowlers in the world, cricket has never become a national game.

New Zealand.-Cricket

is popular in New Zealand, where the standard of play has recently risen so far as to admit of the playing of "test" matches with England and South Africa. Up to 1932, however, New Zealand had failed to win any of these matches ; England and South Africa having each won two.

South Africa.-Cricket

was brought to South Africa by Brit ish troops in the '4os, Maritzburg and Wynberg being the earliest centres, with Pretoria following in the '6os and Johannesburg later still. The standard of play made a real advance after the first visit of a S.A. team to England in 1894, and ten years later a team captained by the old Cambridge cricketer, F. H. Mitchell, only lost three out of 26 fixtures in England, E. A. Halliwell prov ing himself a great wicket-keeper, J. J. Kotze as fast a bowler as any in England, and J. Sinclair an all-round cricketer of very high class. In 1905 the M.C.C. sent out a strong team under P. F. Warner, only to see it lose four out of the five test matches to a side of great all-round strength, the decisive factor being the googly' bowling of R. O. Schwarz, G. A. Faulkner, A. E. Vogler and Gordon White. It was only fair that the S.A. team that visited England in 1907 should be accorded the honour of test matches; they lost the only one of the three that was finished, but only after a desperate fight in which their bowlers had a very fine English batting side in consistent trouble. Their captain, P. Sher well, made a historic 115 to rescue his team from disaster at Lord's. Another strong M.C.C. XI., sent out in 1909, lost the rubber by three matches to two, only Hobbs, who batted most brilliantly, being able to master the googly bowling ; Fauikner, who scored over 2,000 runs for a South African team touring Australia in the following winter, losing four out of the five tests, was at this time perhaps the finest all-round cricketer in the world.From that tour, however, the googly bowlers never recovered, and the side that completed in the Triangular Tournament of 1912 were outclassed and overwhelmed, an inferiority further emphasized by South Africa's heavy defeat at the hands of the M.C.C. XI. which visited her in 1913. Once again Hobbs was superlative, but an even more decisive factor was the bowling of Barnes who, after taking 34 wickets for 282 runs in the three test matches against them in 1912, proved even more difficult on the matting and had all their batsmen, except H. W. Taylor, at his mercy. Since the war the South Africans have visited Eng land in and have been visited by M.C.C. teams in 1922-23, 1927-28, 1930-31. The achievements of South Afri cans during these post-war matches ranged from heavy defeat in 1924, through a progressive improvement of form, to triumph in when they won the rubber. Within recent memory the out standing feature of S.A. cricket has been the batting of H. W. Tay lor, who can be ranked in the very highest class for style and effec tiveness alike: A. D. Nourse has batted for a quarter of a century with wonderfully consistent success. The most important domes tic cricket in South Africa is an inter-provincial tournament, known as The Currie Cup, inaugurated in 1890 and named after Sir Donald Currie who, with Sir Abe Bailey, was the great patron of cricket there. All South African cricket is played on matting, stretched on turf, as at Cape Town, or on ant-heaps, as at the Wanderers' ground, Johannesburg, the headquarters of the coun try's cricket : this undoubtedly handicaps the South African crick eter when he comes to play under conditions native to the game, a fact that is now recognized and supports a growing movement for the cultivation of turf wickets.

Australia.-The

earliest cricket centre in Australia seems to have been Sydney, where the game took root very early in the 19th century, Hobart, Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide all being converted before 1850. Conditions, except at Melbourne, and the standard of play generally, remained, however, somewhat primi tive until the visit of the first English team in 1861-62, a pro fessional combination captained by H. H. Stephenson and organ ized as a business venture by Spiers and Pond, who are said to have cleared over £ 10,00o as a result. Thereafter, thanks to the coaching of English professionals, the enthusiasm of the Aus tralians, and further visits from English teams in 1863-64, and, under Grace's leadership, in 1873, progress was rapid, and a no table milestone was reached when, in March 1877, Australia won by 45 runs the first of all test matches, a success almost entirely due to an innings of 165 by C. Bannerman. A still more decisive step was taken a year later when the first Australian team visited England : most of the fixtures arranged for them were second class, and so little was generally known of them in advance that a famous English cricketer was heard enquiring about their col our, and Lord's was virtually empty when they drove on to the ground to meet the M.C.C. Before the day was over, F. R. Spofforth and H. F. Boyle had made history by dismissing a really strong M.C.C. eleven for 33 and 19, and winning the match for their team by nine wickets. The monopoly of English cricket was now seriously threatened and the threat became a reality when, after a most honourable defeat in the first home test match at the Oval, in 188o, Australia beat England by seven runs on Aug. 29, 1882, in what is still the most famous of these games, a victory celebrated in the Sporting Times by the obituary notice that created the "Ashes" legend. Though Australian batting had made great strides in this decade, and W. L. Murdoch was estab lished as a batsman equal to any but "`'V. G.," with H. H. Massie, a brilliant hitter and A. Bannerman, a great defensive player, it was the trio of bowlers, Spofforth, Boyle and Palmer, supported by a great wicket-keeper in Blackham, that made the team so formidable. Their bowling was a revelation to English cricketers: Spofforth, originally very fast, but at his best fast medium, with a very fast ball, was universally acclaimed the greatest bowler in the world ; his deadly control of his off-break and, on the field, an almost satanic malevolence of bearing, early won for him the still unchallenged title of "the Demon." Two years later an equally strong side lost the one test match that was finished, but had distinctly the best of the two that were drawn; in the latter of these, at the Oval, Murdoch scored 211, still the highest innings made in an England v. Australia match in England, and only a famous ninth wicket partnership of 151 be tween W. W. Read and Scotton saved England. The years that followed were a black period for Australian cricket, and between Dec. 1884 and Aug. 1893, England won 16 of the 21 games fin ished; in part this was due to the dropping away of the old stal warts and the inability of the still limited cricket resources of the country to find at once adequate substitutes, but internal quarrels also contributed, and some of her elevens were far from representative. Moreover, English cricket was very strong indeed at this time; as batsmen, Grace, Shrewsbury and Gunn were at their best, and F. S. Jackson, then the Cambridge captain, made a wonderful debut in the matches of 1893. The Australians had a splendid all-round player in G. Giffen, and a really great pair of bowlers in C. T. B. Turner (nicknamed "the Terror") and J. J. Ferris who, on the 1888 tour, together bowled nearly 20,000 balls and took 534 wickets out of 663 that fell. But their batsmen were no match for such bowlers as Lohmann, Peate, Briggs and Peel, the slow left-handers being then, as now, a particular thorn in Australian flesh.The tide began to turn in the winter of 1894-95 when a very strong team under A. E. Stoddart, for which the captain, A. C. Maclaren, Ward and Brown batted splendidly, and Richardson bowled in his best form, only just won the odd game out of five. Three years later Stoddart's second team was decisively beaten by four matches to one, and in 1899 J. J. Darling's eleven de feated England at Lord's by ten wickets, and drew the other four games. A new and accomplished generation of Australian players had now arrived : Darling himself, and C. Hill, were a very fine pair of left-handed batsmen, S. E. Gregory, a most consistent run-getter, and a brilliant field, M. A. Noble, a great all-rounder, whilst E. Jones's extreme pace, Howell's off-breaks, and Trumble's mastery of length and pace changes made the attack very formid able. An attempt to recover the Ashes by a team under A. C. Maclaren in the winter of 1901–o2 was heavily repulsed in spite of brilliant batting by its captain, and in 1902 Darling again led a team to victory, defeating England by two games to one. The Australians' three runs victory at Manchester and England's one wicket success in the fifth game at the Oval, are historic in the series. The feature of the tour was the batting of Victor Trumper, a modest genius whose effortless brilliancy has never been sur passed.

In the winter of 1903-04 the M.C.C., determined to restore the prestige of English cricket, themselves organized a team which, under P. F. Warner's captaincy, succeeded in recovering the Ashes; the batting of R. E. Foster who, in his first test match innings at Melbourne, scored 287 runs, of Tyldesley and Hayward, the bowling of Rhodes and the surprise effect of J. Bosanquet's googlies, were the deciding factors. The following year England's success was repeated, when F. S. Jackson, winning the toss in all five games and batting brilliantly himself, led his side to victory in the only two matches that were finished. In the next winter, however, the advance guard of a new generation of players recov ered the honours for Australia, defeating a rather moderate M.C.C. eleven captained by A. O. Jones, by four games to one, and in 1909, Noble, a consummate tactician, profited by some ill judged decisions by the English selection committee, and won two out of the three finished games. The very fast bowling of Cotter, the all-round form of Armstrong and Macartney, and the success of the two young left-handed batsmen, Ransford and Bardsley, were the features of the tour; the latter created a rec ord by scoring a century in each innings of the last test match. Once again the pendulum swung over and in the winter of 191I the splendid batting of the opening pair, Hobbs and Rhodes, and the most formidable bowling of Barnes and F. R. Foster, won decisive victory for P. F. Warner's second M.C.C. XI. This tour set the seal upon Hobbs's batting reputation, whilst Australian opinion was unanimous that Barnes was the finest English bowler they had yet seen; he and Foster, whose pace off the pitch was a revelation to his opponents, took 66 wickets of the 95 that fell, but were well supported by J. W. H. T. Douglas. The Australian team that took part in the Triangular Tournament of 1912 was far from representative, and though they easily accounted for the South Africans, they were no match for a very strong England XI.

The war hit Australia much less hard than England and she was soon into her cricket stride again. A tour in England by an Australian Imperial Forces eleven in 1919 served to introduce J. M. Gregory, for whose pace as a bowler the game in England could offer no approach to a parallel. There now followed the greatest humiliation ever sustained by English cricket when her representatives suffered defeat in eight consecutive tests; weak ness in bowling and fielding was mainly responsible for the loss of all five games by the M.C.C. side which toured under Doug las's captaincy, but at home it was the complete inability of the English batsmen to deal with the fast bowling of Gregory and Macdonald, whose energies were carefully husbanded for the tests, well used by an able captain in Armstrong and ably sup ported by the slow bowling of the captain himself and of A. A. Mailey, a most persevering and successful googly bowler. Eng land made a better showing in the last two test matches which were drawn, and heavy though the blow was to her prestige, her cricketers, in the long run, benefited by this reverse which served to recall the cardinal principles of a straight bat and a good length. Three winters later a M.C.C. team, under A. E. R. Gilligan, though only winning one test match in Australia, gave a much better account of themselves. Hobbs and Sutcliffe did wonders as an opening pair, running up over ioo together four times— thrice in succession. Sutcliffe's first four test match innings were 59, 115, 176 and 124, whilst Hobbs, with three centuries, bring ing his total to nine, surpassed Trumper's previous record of six for the series; unfortunately, the body of our batting was disap pointing and failed to profit by the successful starts. Conversely the Australians, time after time, made splendid recoveries from disastrous starts, for which the bowling of Tate was responsible. This young Sussex professional beat even Barnes's figures by tak ing 38 wickets in the five matches, bowling with a fire and persist ency that won universal acclamation from the Australians, who rated his bowling as high as any that had been seen in their country. The English change bowling was, however, very weak. For the first time in cricket history, eight-ball overs were obliga tory, an innovation confined to Australia and since abandoned. These matches, the first three of which ran to seven days apiece, were premonitory of the endurance tests into which, thanks to the pluperfect pitches formed of the Bulli soil, and the intense deter mination of all batsmen not to get themselves out, cricket in Aus tralia seems fast degenerating.

In 1926, after losing 12 tests out of 13 completed, England at last turned the tables, and after bad weather had played a large part in drawing the first four games, won decisively in the fifth at the Oval which was, in any case, to be played to a finish—an inno vation in England—but for which, as it turned out, four days sufficed. Once again it is a case of Hobbs and Sutcliffe, the fa mous pair defying some very accurate bowling on a very difficult wicket throughout the third morning and laying the foundations for a long score ; in the last innings the Australians quite collapsed before some accurate bowling of the old-fashioned type by Rhodes, who had played his first test match 27 years before, and some good fast bowling by a new star, Larwood of Notts. Hobbs, who in the previous year had, at the age of 42, surpassed "W.G.'s" achievement of 126 centuries, batted with marvellous consistency in these five test matches, scoring 486 runs with an average of 81, and easily outstripping Hill's previous record aggregate of 266 for this cricket. Sutcliffe's batting was on the same level. For Australia, Macartney batted as brilliantly as ever, and Woodfall and Ponsford did excellently on this, their first tour : but the at tack was the weakest for many years and sadly lacked medium paced spin bowling. England's victory created enthusiasm.

Up to and including the tour of the Australian team visiting England in 1934, 134 test matches have been played; Australia won 53 (38 in Australia), England 52, 29 being drawn. Consid ering the initial handicap of inexperience, the disparity in pop ulation, and the natural difficulty of adapting themselves to English conditions, Australian cricketers may well be proud of such a record ; but it is to be remembered that the climate favours athletic development, that the teams that have visited the country from England have often been far from represent ative, and that Australian cricketers, especially the bowlers, play much less first-class cricket than their opponents, and avoid the staleness and overwork which has curtailed many an English bowler's best powers. In a domestic season in Australia, first-class cricket is virtually confined to the inter-state matches of the Sheffield Shield competition, so called because played for a cup presented by Lord Sheffield at the close of the tour which he or ganized to Australia. in 1891-92. In the winter seasons of 1926 and 1927, W. H. Ponsford scored centuries in eleven consecutive matches in these games; and in 1929-3o D. G. Bradman made 452 not out for N. S. Wales v. Queensland at Sydney—the highest individual innings ever played in a first-class match.

The tables opposite summarize the work of the outstanding players in England v. Australia matches to the close of 1934 tour. Amateur Cricket.—Though economic pressure and possibly a changing standard of values is steadily reducing the number of amateurs able and willing to play first-class cricket with any regularity, and though the highest standard of technique must al ways depend upon professional cricketers, especially bowlers, yet amateurs have in the past played a vital part in the game's de velopment, and it cannot to-day dispense either with their leader ship, or with the spirit of enterprise and the attractive method that, as a rule, characterizes their play. Though county elevens have been successfully captained by professionals, notably Notts., and Yorkshire in the middle of the i 9th century, and though such men as Lilley of Warwickshire have captained the Players' eleven with marked ability, professionals as a whole would not welcome the responsibilities involved in regular captaincy, which naturally extend far beyond the field of play. It is not too much to say that some counties have, for a time, at least, been made by their cap tains, amongst whom the outstanding figures in the last half century are perhaps Lord Hawke (186o-1938) (Yorks.), Lord Harris (Kent). A. N. Hornby (Lancs.), J. Shuter (Surrey), I. D. Walker, A. J. Webbe and P. F. Warner (Middlesex), A. O. Jones (Notts.) and S. M. J. Woods (Somerset).

There have, of course, been brilliant professional batsmen— Hammond in 1927 was probably the most attractive in the world —but it is only natural that men who depend on the game for their livelihood should concentrate first on security and that it should be left to the amateur to supply what has been termed "the champagne of cricket." Certainly the great stylists in cricket history have often been amateurs, e.g., C. G. Taylor (1817- 1869) , R. Hankey (183 2-1886) , R. A. H. Mitchell (1843-1 905) , A. Lyttelton (1857-1913), A. G. Steel (1858-1914), A. E. Stod dart (1863-1915), L. C. H. Palairet (187o-1933), A. C. Maclaren (1871– ), the brothers, H. K. (1873– ) and R. E. Fos ter (1877-1914), R. H. Spooner (188o-- ), D. J. Knight (1894– ) and A. P. F. Chapman (1900– ) . Naturally, the ranks of the hitters have been mainly recruited from amateurs, the two greatest of them, by general consent, being C. I. Thorn ton (1850-1929) and G. L. Jessop (1874– )• If Thornton was consistently the longer driver (several hits of 150-16oyd. are au thenticated for him), Jessop, thanks to his extraordinary quick ness of foot and freedom of swing, was the more versatile and the fastest scorer that the game has known. In 190o he made 15 7 runs against the West Indians between 3:3o P.M. and 4:3o P.M., and a rate of ioo runs an hour was normal with him when at his best.

In bowling, the amateurs have, as a rule, been definitely inferior to the professionals, especially in accuracy, but they have num bered amongst them some of the greatest fast bowlers, e.g., Alfred Mynn, Harvey Fellows, a positive terror in the '4os, S. M. J. Woods, C. J. Kortright, W. Brearley and N. A. Knox. Of all bowlers, Kortright is still thought to have been the fastest. Men tion must also be made of one or two slow spin bowlers who stood, in their respective epochs, as figures of creative originality: such were David Buchanan. a slow left-bander who did wonders for "the Gentlemen" between 1868 and ' 74 ; "W. G." himself who, with his flight and generalship was for two decades "the best change bowler in the world"; A. G. Steel who re-discovered the leg-break in the later '7os, and B. J. T. Bosanquet, the inventor of the googly at the beginning of this century. Similarly as V. E. Walker was almost alone in bowling lobs in the middle of the 19th century, so D. L. A. Jephson and G. H. Simpson-Hayward were the sole, though successful, exponents of the art 5o years later.

The Gentlemen v. Players Match.

In any purely domestic season the match played in the middle of July at Lord's between the best amateurs and professionals, stands as the high-water mark, and selection for these elevens is a much coveted distinc tion. The match was first played in i8o6, and not again until 1819, since when it has been played regularly. For many years, the Gentleme.jl were no match at all for the Players, and various handicaps, odds, given men and unequal sized wickets, were vainly tried to equalize the sides. The '4os brought them a spell of some success, due largely to Alfred Mynn, but from 1850-64, the Play ers won every match except that in 1853 when Sir Frederick Bathurst and M. Kempson bowled unchanged throughout both innings. In these dark days the amateurs' batting was hopelessly outclassed. In 1865 "W.G." played for the Gentlemen for the first time, and in the next 16 years he was only twice on the losing side; for this wonderful run of success his personal prowess both with bat and ball was mainly responsible. No cricketer has a record for these matches even comparable with his, but he was well supported by the bowling of his brother, E. M. Grace, and of D. Buchanan, whilst a strong vein of batting talent was running from the 'varsities, Eton and Harrow, notably in the persons of W. W. Yardley, A. Lubbock, the Lytteltons and a little later, A. G. Steel, one of the greatest all-round amateur cricketers, and A. P. Lucas. The Players recovered most of their lost ground in the '8os, but the next decade saw honours fairly divided: in 1894, F. S. Jackson and S. M. J. Woods bowled un changed through the match and won it for a side, the average age of which, leaving out "W. G." was but 25; two years later, one of the strongest of all elevens that have represented the Gen tlemen, won a notable fight by six wickets, and in 1898, a match timed to coincide with "W. G.'s" 5oth birthday, produced cricket wholly worthy of the occasion. The fast bowling of Woods and Kortright, and the batting of Shrewsbury, lent peculiar distinc tion to this epoch.In the present century the match has continued to provide much splendid cricket, though the amateurs of recent years have found the task of dismissing the very strong batting sides of the Players increasingly beyond their powers. In the opening match of this period, R. E. Foster made 102 and 136, but the Players won the game by scoring over 500 runs in the last innings. Three years later the Gentlemen turned the tables when, after being outplayed for two days, they made soo for two wickets—C. B. Fry (232 not out) and A. C. Maclaren (168 not out), adding 3o9 runs in less than three hours.

The centenary celebration in 1906 is always known as "the fast bowlers' match" ; Fielder took all 1 o wickets in the amateurs' first innings, and N. A. Knox and W. Brearley, with H. Martyn of Somerset standing up to both behind the stumps, combined in a terrific in the end, successful assault. In the years just before the World War, the Players were very strong, Barnes bowling superbly, and Hobbs inaugurating an extraordinary series of batting achievements ; but the Gentlemen won a fine victory in 1911, and again in 1914, when J. W. H. T. Douglas bowled with splendid persistency and control of swerve. In the matches since the war the amateurs have won only in 1934, though A. P. F. Chapman and D. R. Jardine have batted admirably. Hobbs, in these games, has a remarkable record, having now scored five centuries since 1919, four in successive years. Amongst the best teams that have appeared in this match may be noted the Gen tlemen elevens of 1878, 1896, 1898, 1906 and 1911, and the Players in 1887 and 1911, whilst some of their post-war sides, if not reaching the highest bowling standard, have been as strong in batting as any of their predecessors. Though never enjoying the same prestige as the Lord's fixture, similar matches between Gentlemen and Players have taken place regularly at the Oval since 186o, at Scarborough since 1885 during the very popular festival there at the end of the season, and, intermittently, at Prince's, London, Brighton and Hastings.

University Cricket.

Though by no means enjoying the virtual monopoly that they once did, the universities of Oxford and Cambridge are still the chief nurseries of amateur cricket the competition for cricket "blues" is keener than ever, and for a young cricketer there can be no more thrilling and exacting moment than his first appearance in the University match. This game was first played in 1827, when Charles Wordsworth (0.) and Herbert Jenner (C.) were captains. With the exception of five games, all at Oxford, it has always been played at Lord's and, apart from the war years, regularly since 1838. Of the 91 matches now played, Cambridge has won 43, Oxford 36, and 10 have been drawn. The match has produced sensations in plenty, notably the finishes of 1870 when F. C. Cobden "did the hat-trick" with the last three balls to win the game for Cambridge by two runs, and of 1875 when the Oxford captain, A. W. Ridley, put himself on with "lobs" at the crisis and won the match by six runs. By common consent the Cambridge XI. of 1878 was the best that has ever appeared in the match ; they won all eight matches they played, annihilated Oxford, and beat the Australians by an innings. The brothers, E. and A. Lyttelton and A. P. Lucas were splendid batsmen, Morton a destructive fast bowler, and A. G. Steel, then a freshman from Marlborough, almost the best all-round player in England. The Cambridge side of 1882 also beat the Australians and was very strong, and so were those of 189o--93 in which G. MacGregor kept wicket to the fast bowling of S. M. J. Woods, and F. S. Jackson played himself into an undisputed place in the England XI., and as many as eight men subsequently appeared for the Gentlemen at Lord's. Since the war they have had good teams in 1920 and 1922. For Oxford the elevens of 1863-4-5 under the captaincy of R. A. H. Mitchell were very strong ; M. C. Kemp led a fine side in 1884 which in cluded seven freshmen, that beat both the Australians and Cam bridge by seven wickets, whilst the batting, and even more the fielding, of H. D. G. Leveson-Gower's team which in 1896 scored 33o in the last innings for six wickets, will long be remembered. It is impossible here to refer to individual performances and players, but mention must be made of the distinguished part played by some families in the match : such were the Lytteltons, Fords, Studds and Ashtons for Cambridge ; the Riddings, Fosters and Evans for Oxford. The Cambridge brothers, C. E. M. and E. R. Wilson, have an astonishing family record. The University match may no longer provide so much of the "champagne of cricket" as of old, but it still remains a unique feature in the English season, a focus for ardent patriotism, a rendezvous where generations of friends and foes renew happy memories, and an arena where the best cricket, especially the fielding, reaches a high level, and the worst is raised to a .higher power by the chivalrous vigour with which the game is fought. Both universities have fine grounds, known at Oxford as "the Parks," at Cam bridge as "Fenners," where a professional coaching staff is en gaged. The colleges also have admirable grounds, though in the last generation lawn tennis has made distinct inroads into college cricket.School Cricket.—Cricket being in origin a boy's game, it is not surprising to find the schools supplying some of our earliest references to it ; it was being played at the Free School at Guild ford in the middle of the 16th century, the Wykehamists were playing it on "Hills" Ioo years later, at Eton the game was firmly established by the beginning of the 18th, the duke of Marl borough was probably playing it at St. Paul's a few years earlier, and Westminster provided at least three men to form the "Star and Garter" committee that revised the laws in 1774. Cricket at Harrow was of rather later growth, possibly introduced by an Etonian headmaster ( !) but certainly established well before the end of the 18th century. The most famous of all school matches, Eton v. Harrow, was first played at Lord's in 1805, the poet Byron being a member of the Harrow team; from 1822 this game has been played virtually without a break and of exactly Ioo matches now played, Eton has won 40, and Harrow 35. Between 1851 and 1869 Eton only won once, and again only once between 1888 and 1903, but the pendulum swung with a vengeance in this century and Eton had a run of successes. Once quite a domestic affair, the match has long constituted almost the climax of the London season and now attracts a huge and bril liantly dressed crowd, an important item in the financial budget of the M.C.C. who dispense a large yearly grant to support cricket at the two schools. In 1825 Harrow first met Winchester at Lord's, and a year later Eton followed suit, thus inaugurating what was known as "the Schools' Week," a triangular contest which lasted till 1854, when Winchester withdrew subsequently playing Eton home and home matches, and reviving the Harrow match after the war. For more than half last century these three schools supplied a very high percentage of university "blues," with Rugby an easy fourth, but following the lead of Uppingham, who had five Cambridge blues in 1876, other schools, noticeably Malvern and Repton, have successfully challenged that monopoly, and the composition of the university teams is now quite catholic, with some of the most notable of recent performances standing to the credit of Rhodes scholars and other students from the Dominions. Rugby and Marlborough, Cheltenham and Hailey bury, Tonbridge and Clifton all play each other at Lord's at the end of the summer term, and these matches are now followed by representative games, organized by the M.C.C., between an eleven selected from the schools that play at Lord's and "the Rest," and subsequently between a public school eleven and the Army. In 1926 a XV. of the public schools played the Australians. Cricket at the schools, from the junior nets at a preparatory school to the matches just mentioned, is now intensively organized, and young cricketers of promise are systematically coached; of the professional coaches, the most famous was H. H. Stephenson at Uppingham in the '7os; of amateurs we may cite the Hon. R. Grimston and the Hon. F. Ponsonby for Harrow, and R. A. H. Mitchell and C. M. Wells for Eton, whilst many others, if less illustrious, have worked most unselfishly and with splendid results in the same cause. Largely as a result the general standard of school cricket has shown a steady advance, immense in the aggre gate since, say, 186o: the best school batsmen have always been able to take their places at once in first-class cricket, but bowlers who have made a similar immediate mark are so few that we can specify A. G. Steel and H. Rotherham of Uppingham, C. L. Town send of Clifton, E. M. Dowson of Harrow, J. N. Crawford of Repton and G. T. S. Stevens of University College school: the latter in 1919 was actually selected to play for the Gentlemen at Lord's, whilst still at school.

Evolution of Technique.—Cricket, the boys' game, was no doubt played in Tudor and perhaps even in Plantagenet times, in a haphazard, makeshift way; in the woodland districts of the Weald, the natural base for attack and defence was the tree "stump," of which the exigencies of Cinque Ports shipbuilding would provide no lack; the mark being low, it would be natural to "bowl" at it. On the down lands, however, the shepherd lads used another mark, the hurdle gate into their sheep pens, consisting of two uprights and a crossbar resting on their slotted the lat ter is still called by stockmen a "bail" and the whole gate a "wicket," deriving its name from the A.S. wican, to give way, i.e., the place where the pen yields and admits entry. The fact that the bail could be dislodged when the wicket was struck made this preferable as a mark to the "stump," and the "woodmen" were converted to its use, preserving, however, a memory of their original habit by applying the term stumps to the hurdle uprights.

The dimensions of this wicket would at first vary widely in different districts; Nyren speaks of "a small manuscript" en shrining the recollections of an old cricketer about the game as he knew it at the beginning of the 18th century. This describes the wicket as 'ft. high by 2f t. wide, with a hole between the up rights into which the ball had to be "popped" (cf. popping crease) to run-out or stump a batsman ; this tradition is also supported by a picture at Lord's, No. 17 in the M.C.C. collection, and the wider than high wicket by other representations of the game. It is probable, however, that this practice was local to the Western Weald, and that the true tradition of the game's home, Kent and East Sussex, is preserved in the first official regulations that we know, the "London Laws" of 1744. These laws clearly represent a sophisticated edition, probably by the cricket committee of the Artillery Ground. of a much earlier and nrohahlv oral version indeed "H. P-T's" pamphlets (see Bibliography) have convinc ingly disentangled the new from the old. The other important authority for the earliest "regulation" game is a Latin poem by William Goldwin, sometime scholar of Eton and King's, published in 1706 as one of a collection called "Musae Juveniles." The original wicket then was 22in. by 6in., the popping crease (or "scratch"—whitening did not come in until "W.G's" time) was 46in. in front of it, and the pitch was 22yd. long. These measure ments all correspond with divisions or multiples of the early Tudor units of length measure, the "gad" of 16 zf t. and the ell or cloth yard of 45 inches. The further evolution of the wicket took place as follows : A middle stump was added in, or shortly after, 1775; by two inches had been added to the height and one to the width, and in 1817 the size of the wicket was increased to its present dimensions (2 Tin. by 8in.) and, perhaps a year later, the original bail was split into two.

The ball was probably much the same in the 17th century as it is today : Duke of Penshurst told Farington, the diarist, in 1811 that his family had been making cricket balls for 25o years. It was certainly leather-covered (coriaceus orbis in Goldwin) and crimson dyed, almost certainly hemp or hair stuffed. By the laws it might weigh anything between five and six ounces; its present precise specifications in weight and circumference were laid down in 1774 and 1838 respectively.

The primitive bat was no doubt a shaped branch of a tree; at the beginning of the 18th century it resembled a modern hockey stick, but was considerably longer and very much heavier, well adapted for dealing with the only form of attack, then at least properly called "bowling." It has been customary to credit the Hambledon men with the invention of "length-bowling," but a poem, "The Game of Cricket: an Exercise at Merchant Taylors' School," published in The Gentleman's Magazine in Oct. 1756, and conceivably the work of James Dance (Love), who entered that school in 1732, refers to the ball as "now toss'd, to rise more fatal from the ground, exact and faithful to the appointed bound," which looks uncommonly like a cult of "length." It is at least certain that the Hambledon cricketers elaborated this instinct into an art : David Harris, learning his lesson from Richard Nyren, became a great bowler with the three sovereign qualities of length, pace and quickness of rise from the pitch. In reaction the bats men, following the example of John Small of Petersfield, one of the most picturesque characters in Nyren's pages, evolved a new technique, meeting the length ball with the straight bat, shortened in the handle and straightened and broadened in the blade; for a time perhaps their play was rather defensive, "puddling about the crease," but a new generation of Hambledon men opened up the game by forward play, quick-footed driving and the cut. Even Harris's bowling was no greater than the batting of William Beld ham (1766-1862) who "took the ball as Burke did the House of Commons, not a moment too soon or too late." In spite of the combination of length with break and swerve and flight, with which the Hambledonians, Lamborn, Noah Mann and Tom Walker are respectively credited, or rather because of the scarcity of men who could master and maintain those arts, the batsmen steadily asserted their superiority, even after the attempt of one, "Shock" White of Reigate, to use a bat of prepos terous width had been defeated by the legislators of 1774 who limited its width to 41in. ; about the same time the original pro vision of "standing unfair to strike" was elaborated into the first l.b.w. law by which the umpire was confronted with the impossible task of deciding whether such obstruction had been deliberate. With the dawn of the 19th century, most bowlers seem to have been favouring the high-tossed, lobbing variety, originally evolved by Tom Walker of Hambledon, hailed by his contemporaries as "baby-bowling," but at first, no doubt by reason of its novelty, highly successful. But the batsmen, notably Beldham, and a lef t handed hitter, John Hammond, soon learnt to "give her the rush," and run-getting once again rapidly increased.

An answer was found in the next great bowling development, "the Round Arm Revolution," or, as it was then called, bowling of the "March of Intellect" style. Though Tom Walker had appar ently attempted something of the sort bef ore the break up of the Hambledon club, and been barred for his pains, the true apostle of the new bowling seems to have been one John Willes of Sutton Valence, inspired, it is said, by the model of a cricketing sister who used to bowl, or throw, at him in practice. From 18o6 to 1822 Willes persevered in his missionary endeavour in face of determined opposition, until he was no-balled for throwing in a great match at Lord's and rode out of the ground and the game for ever. His mantle fell on two great Sussex bowlers, William Lillywhite and James Broadbridge who, perfecting the new style, carried all before them. Eventually, in 1827, three "experimental matches" were played between Sussex and All England, of which Sussex won the first two, and a reconstituted England side the third. Controversy raged furiously, but the M.C.C. wisely moved with the times, though the reshaping of Law X. to their satisfac tion caused them great difficulty; in 1835 it countenanced the hand being raised as high as the shoulder, but ten years later the bowler was taking such liberties that the umpire was then ex pressly forbidden to give him the benefit of the doubt.

The new style was rapidly attended with a great increase in pace : of the new "fast and ripping" school, Alfred Mynn, Samuel Redgate and John Wisden were the first great exponents. As time went on bowlers tended to raise the hand higher and higher in defiance of the law, until it became more honoured in the breach than the observance. Eventually, Edgar Willsher of Kent was no-balled for throwing in a big match at the Oval (Aug. 27, 1862), and the whole fielding eleven, except its two amateur members, left the field in protest. This brought matters to a head and in 1864 the bowler was officially accorded full liberty to bowl. There has, at intervals since, been trouble over the "throwing" question. In the mid-'8os, Lancashire had three offenders in their team, whose activities were, in the end, curbed by the stand taken up by Lord Harris. There was more unfair bowling in the nineties, but the County captains in 190o took concerted action, and to-day the evil is virtually unknown.

With the exception of William Clarke, V. E. Walker and Tinley, of Notts, all three successful "throw-backs" to the old high and lobbing school, most bowling continued to be fast through the middle of the 19th century, and good though such wicket-keepers as T. Box (Sussex), T. Lockyer (Surrey) and Herbert Jenner (C.U.C.C.) were, the role of long stop became most important : in fact, two long stops were at times necessary for dealing with some of the very wild bowling that was all too common, especially in amateur cricket. The number of wides in some of the university and big school matches of this period was really preposterous. Against this onslaught the batsman learnt to protect himself with additional armour : H. Daubeny invented pads in 1836 and N. Felix the tubular batting glove about the same date, whilst in Nixon greatly increased the resiliency of the bat by inventing the cane handle. Fortified by these aids, the batsman refused to be intimidated and actually developed the scope of his art. George Parr, the "Lion of the North," exhibited the perfection of leg hitting; Julius Caesar of Surrey, experimented with "the pull"; William Caffyn of Surrey and Ephraim Lockwood of Yorkshire excelled in the cut. Carpenter of Cambridgeshire was a great back player who was, at the same time, quick on his feet to punish slow bowling, and Thomas Hayward the elder, his compatriot, the first man to develop forcing strokes to the on off the over-pitched ball, whilst the classic principles of elegance and the straight bat, inherited through Fenner and Fuller Pilch, were transmitted in apostolic succession by the Notts. players, Joseph Guy and Dick Daft, to the later generation of Shrewsbury and William Gunn. Though, however, these champions, all, be it noted, professionals, held their own with any bowling they had to meet, the fast bowlers had less gifted men, and dearly all amateur batsmen, rather at their mercy, nor is this surprising when we recall that such men as Jackson of Notts. and Tarrant of Cambridgeshire were as fast as any men bowling to-day, whilst the grounds were incomparably worse. There were, in fact, in the '5os and '6os, only four grounds—The Oval, Brighton, Canterbury and Fenners—where good wickets were the rule, and until 1849, when permission was first given to sweep and roll the pitch at the beginning of each innings, it was unlawful to touch it from beginning to end of a match.

Such was the general state of cricket when W. G. Grace (b. 1848) played his first county match in 1864. Grace is still ac claimed by universal consent the greatest all-round cricketer that the game has yet known and volumes have been written upon his career. No one player has had so decisive an effect on the game, perhaps on any game. By his extraordinary achievements, arrest ing appearance (he was a big man with a black beard who always wore the M.C.C. red and yellow cap), and of lovable, if at times, cantankerous, personality, he concentrated upon himself, and, through himself, upon the game, an attention quite unparalleled before ; wherever he went thousands swarmed to watch ; he was, at least, as well known to every class of Englishman as was Glad stone at his zenith. His personal prowess restored the prestige of amateur cricket in the Gentlemen v. Players matches at Lord's. As a batsman, Grace revolutionized the art : "he turned it from an accomplishment into a science ; he united in his mighty self all the good points of all the good players and made utility the criterion of style; he turned the old one-stringed instrument into the many-chorded lyre. But in addition he made his execution equal his invention." Incidentally, Grace killed fast bowling ; to the very end of his career, pace, even on a fiery wicket, had no terrors for him, and in his prime he dealt with it so mercilessly that its exponents were almost afraid to bowl within his reach.

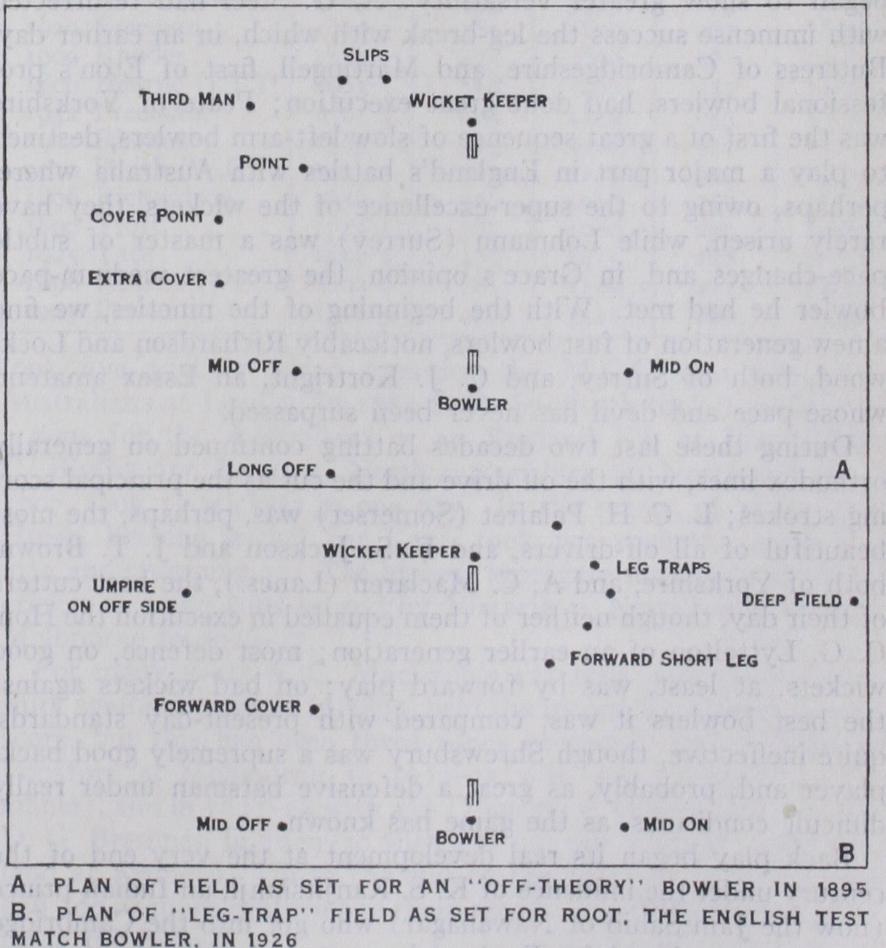

This decline of fast bowling coincided, in the '7os, with a rapid improvement of grounds, due to the advent of the heavy roller even more than to the perfection of the lawnmower, and under "W.G.'s" example, batsmen generally, though they never suc ceeded in imitating his intensely individual methods, adopted a more generally aggressive attitude to the attack. The bowlers sought to hold their own by concentrating on accuracy of length at the sacrifice of pace, and a new school of slow or slow medium bowlers gradually emerged, with Alfred Shaw of Notts. as its model and master. The astonishing accuracy of Shaw's bowling is well attested by the fact that in a cricket career of 3r years he actually bowled 16,922 maidens out of a total of 24,700 overs, his 2,o51 wickets costing him less than 12 runs apiece. The bowlers of this era often sought to curb further the batsmen's aggression by keeping the ball some distance wide of the off stump ; of this "off-theory" bowling, as it was called, the Gloucester amateur, R. F. Miles, is said to have been the originator; Attewell of Notts. was its greatest exponent ; it was accompanied, of course, by a concentration of the fieldsmen on the offside of the wicket, mid on very often being the solitary man left to guard the "on." A few natural "rebels," notably W. W. Read (Surrey) took advan tage of the opportunity to defy the canons of orthodoxy, follow the example of E. M. Grace ("W.G.'s" elder brother) and pull the off-ball round to the denuded on, but for the most part the off theory was countered by a policy of masterly inactivity. It was nothing out of the way, especially with some of the northern professionals, to see a whole over allowed to go by with no attempt made to play the ball. Indeed, the pace of some county cricket became so funereal that interest in the game sensibly flagged and attendances fell off. In a Yorks. v. Notts. match in 1887, three fine days and a fast wicket produced 702 runs in 625 overs. Cricket was in some danger of falling victim to an academic formalism. From such a fate it was saved by a transfusion of new and vigorous blood.

Profiting by the coaching and example of English professionals, some of whom stayed on in their country as coaches at the end of the earliest tours and working at the same with immense enthusi asm, the Australians developed their cricket, especially their bowling, so rapidly that when, on their first visit in 1878, they startled England and f our years later actually defeated her full strength, it was recognized that a further evolution in technique had taken place. Their great bowlers, notably Spofforth, Boyle, Allen and Palmer, combined pace with spin and variety of flight, bowled much straighter than was the convention in Eng land and made full use of a much more elastic field; when the pitch helped his off break, Spofforth would get many wickets from catches by Boyle standing in the then unprecedented place of silly mid-on, some six or seven yards from the bat. Blackham, in standing up to a bowler of Spofforth's pace, dispensing with a long-stop and taking the ball cleanly even on the leg side, set a new standard in wicketkeeping. Gradually English bowling, too, began to show greater versatility : A. G. Steel had resurrected with immense success the leg-break with which, in an earlier day, Buttress of Cambridgeshire, and Martingell, first of Eton's pro fessional bowlers, had done great execution ; Peate of Yorkshire was the first of a great sequence of slow lef t-arm bowlers, destined to play a major part in England's battles with Australia where, perhaps, owing to the super-excellence of the wickets, they have rarely arisen, while Lohmann (Surrey) was a master of subtle pace-changes and, in Grace's opinion, the greatest medium-pace bowler he had met. With the beginning of the nineties, we find a new generation of fast bowlers, noticeably Richardson and Lock wood, both of Surrey, and C. J. Kortright, an Essex amateur, whose pace and devil has never been surpassed.

During these last two decades batting continued on generally orthodox lines, with the off drive and the cut as the principal scor ing strokes; L. C. H. Palairet (Somerset) was, perhaps, the most beautiful of all off-drivers, and F. S. Jackson and J. T. Brown, both of Yorkshire, and A. C. Maclaren (Lanes.), the best cutters of their day, though neither of them equalled in execution the Hon. C. G. Lyttelton of an earlier generation ; most defence, on good wickets, at least, was by forward play; on bad wickets against the best bowlers it was, compared with present-day standards, quite ineffective, though Shrewsbury was a supremely good back player and, probably, as great a defensive batsman under really difficult conditions, as the game has known.

Back play began its real development at the very end of the century under the influence of K. S. Ranjitsinhji, an Indian prince (now the Jam Sahib of Nawanagar) who got into the Cambridge XI. in 1893, played for England in 1896, and was a batsman of great and original genius whose theory and practice has often been summed up in the cliche "play back or hit." He and his friend and disciple, C. B. Fry, at this time the most versatile athlete in Great Britain and as a batsman profoundly influenced by his association with the Indian prince for Sussex, also developed on-side play to an extent undreamt of before, most noticeably in the hook stroke to the short ball and the forcing strokes wide of mid-on from balls pitching on the line of their legs or of the leg-stump. Indeed, these two batsmen may fairly be said to have laid down the lines upon which first-class batting has subsequently moved. Naturally this made for a strengthening of the on-side field, a tendency already set in motion by the success of a group of leg-break bowlers, notably C. L. Townsend, Braund, C. M. Wells and Vine, who bowled at the batsman's legs and leg-stump with considerable spin from leg, and had as many as six of their fieldsmen on the on-side. A reductio ad absurdum of this form of attack was, however, provided by W. W. Armstrong who, in two test matches for the r 905 Australian side, bowled wide of the batsman's legs with virtually all his field to the on, with the sole object of slowing down the English rate of scoring.

The opening years of this century show an orgy of run-getting and drawn games, so formidable as to induce serious debate by the M.C.C. on the reforms desirable to restore a fairer balance be tween bat and ball ; a general meeting of the club agreed so to alter Law X. as to make it no longer necessary for the ball to pitch straight to secure a verdict of l.b.w. The majority, how ever, though large, was not the two-thirds requisite for any alter ation in the laws proper, and the M.C.C. contented itself with a ukase to the counties denouncing the over-preparation of pitches which, at this time, with the help of special clay-dressing—most noticeably Nottingham marl—and of binding solutions such as liquid manure, the groundsmen up and down the country had reduced to a fine art. This appeal by the M.C.C. met with considerable success.

The heavy run-getting of this epoch is not, however, to be put down mainly to the ease of the conditions; it was rather due to a generation of great batsmen—a striking number of them were amateurs—who triumphed over much varied and formidable bowling by methods at once more attractive, more versatile and more individualistic than obtain to-day. As a spectacle, English cricket has never been better than in the years r 9oo–r 905.

The next factor to influence the game--and it did so profoundly —was the so-called "googly" bowling, or the art of bowling at a slow or, at the most, slow-medium pace, an off-break with what appeared to be a leg-break action. This bowling was invented by B. J. T. Bosanquet, first successfully exploited by him in Australia in the winter of r 903-04, learnt from him by his Middlesex col league, R. O. Schwarz, who took the art with him to South Africa, there to see it brought to something like perfection by himself, G. A. Faulkner, A. E. Vogler and Gordon White. The bowling of these four men, whether on their native matting in 1905, or as visitors in 1907 on our own turf wickets, created a real sensation : R. E. Foster, the England captain in the Tests of that year, hailed Vogler as the most difficult bowler in the world, and both he and A. C. Maclaren expressed grave misgivings as to the effect of googly bowling on cricket generally, suggesting that the batsman, if not positively immobilized, would at least be limited to cramped defence. Fortunately the difficulty of combining the googly with a good length, due largely to the physical strain involved, proved too great for most who attempted it, though both England and Australia have since produced successful bowlers of this type— notably D. W. Carr, Freeman, Richmond and R. Tyldesley in England ; H. V. Hordern, A. A. Mailey and Grimmett in Australia.

Nevertheless, the googly's influence on batting, if not decisive, has been considerable ; it has reinforced the tendency towards back-play already discernible before its advent, but on new and unfortunate lines. In his anxiety to delay his stroke until the line of the break shall have declared itself, the batsman tended to play back even to the over-pitched ball, and to reinforce his bat with his legs as a second line of defence. Only too often he contracted the habit of moving back and across the wicket with the right foot, before he knew the length of the ball, facing down the pitch with both feet pointing towards the bowler. The initial position inevit ably denied to him the use of left-arm, elbow and shoulder, and with them the possibility of making any strokes except those executed with the right forearm, i.e., the jab, the hook and the glide.

To such a practice another factor besides the googly substan tially contributed. Ever since Noah Mann, of Hambledori, there have been at intervals in cricket history, bowlers accredited with the gift of the "swerve," i.e., the gift of being able to make the ball change the direction of its flight in the air: the claim was made for Alfred Mynn in the '3os, and can be fully substantiated for Allen of Australia, Walter Wright of Kent, and Rawlin of Middlesex 5o years later, but such men had no idea how and why they swerved; then the American baseball pitchers developed the art, Albert Trott of Middlesex and M. A. Noble of Australia came under their influence, and before the first decade of the new century was ended, swerving was a common phenomenon in English cricket; most right-handers swerved from leg to off and bowled for catches in the slips, but some, such as the great pioneer of the style, J. B. King of Philadelphia, could swerve the ball in from the off, and the left-hand bowlers, such as Hirst and F. R. Foster, were often deadly with the new ball, supported as they were with a semi-circle of close-up fielders, known as leg-traps, ready to catch all edged or mishit balls. Some bowlers, notably Relf, Barnes and J. W. H. T. Douglas, could swerve either way, at least into a head wind. The ability to continue to swerve after the gloss begins to wear off the ball is contingent for most bowlers on one or more of such factors as a suitable breeze, a heavy atmos phere, favourable surroundings, e.g., trees. Contemporary, and in part connected with these developments, there came a much more intelligent and elastic use of the field ; great tacticians, amongst whom the Australian captain Noble was unsurpassed, would study each batsman's strokes individually, and block them with an inner and an outer ring. The on-side became increasingly guarded.

The combined influence of the googly and the swerve dominated English batting in the years immediately after the war with disas trous effects; with very few exceptions the leading batsmen con centrated on back-play, and the right-hand on-side strokes, aban doning almost entirely the drive and the cut ; the weakness of English bowling in that period encouraged them to believe in their method, but they were cruelly undeceived by their own helpless ness before the pace of Gregory and Macdonald, and the accuracy of Armstrong of the 1921 Australian team. Since then English batting has been slowly achieving a reasonable compromise be tween the new style and the old ; it is undeniable that, under the influence of "unlimited" test match cricket in Australia and the yearly increasing rivalry and publicity of county cricket, the game is now less attractive as a spectacle than it was. Admittedly the general level of defence, especially on difficult wickets, is greatly advanced, but first-class batting is much more stereotyped, and less versatile and adventurous. Fortunately there have still been a few—Hobbs, Woolley and Macartney in particular—to prove that genius cannot be fettered, and that it is possible to master the new bowling without sacrificing the glamour and grace of the old batting; but for the most part, first-class cricketers, of whom all other cricketers are only too imitative, have subscribed to the modern doctrine that, even in a game, efficiency must decide.

Some Records and Curiosities.

A list of a few outstanding cricket achievements, compiled by permission, mainly from Wis den's Alranack, in first-class cricket may be interesting.The highest individual innings in a test match was W. R. Ham mond's 336 not out v. New Zealand at Auckland (1932-33) ; six centuries in successive innings in first-class cricket were made by C. B. Fry in 1901 ; 16 centuries in one season of first-class cricket by J. B. Hobbs in 1925; 189 runs in 90 minutes by E. Alletson for Notts. v. Sussex at Brighton in 1911; 555 runs for a first wicket partnership by P. Holmes and H. Sutcliffe for Yorkshire v. Essex at Leyton in 1932; 3,518 runs in a season's first-class cricket by Hayward (T) in 1906. W. G. Grace, be tween 1865 and 1908, scored 54,896 runs and took 2,876 wickets in first-class cricket. In 1895, Richardson (T) took 290 wickets, while in the second Australian tour (188o), F. R. Spofforth took wickets in England; G. H. Hirst in 1906 scored 2,385 runs and took 208 wickets. The feat of scoring over 1,000 runs and taking over zoo wickets in the same season has been ac complished by Rhodes (W.) on 16 different occasions. W. G. Grace played his first match for the Gentlemen v. the Players in 1865 and his last in 1906, scoring in these games 6,008 runs, with an average of 42.6o, and taking 271 wickets for 18.78 runs each. For Australia v. South Africa, at Manchester, in 1912, T. J. Matthews took three wickets with successive balls in each inning —a feat without parallel in test matches. In 1896 A. D. Pougher took five wickets for o runs for the M.C.C. and Ground v. Australians at Lord's. In 1884 F. R. Spofforth took 7 wickets for 3 runs for the Australians v. an England XI. at Birmingham.

C. Blythe for Kent v. Northamptonshire at Northampton, in 1907, took 17 wickets in one day. In the season of 1913, F. H. Huish, keeping wicket for Kent, took 102 wickets, catching 70 men and stumping 32. The highest aggregate innings in first-class cricket is 1,107 runs scored by Victoria v. New South Wales at Melbourne in 1926-27.

For many years A. C. Maclaren's 424 runs, scored for Lanca shire against Somerset in 1895, held the record for a single innings score, but this has been three times exceeded : twice by W. H. Ponsford at Melbourne, in 1922-23 with 429 (Victoria v. Tas mania), and in 1927-28 with 437 (Victoria v. Queensland) ; and by D. G. Bradman in 1929-30 with 452 not out (N.S.W. v. Queens land at Sydney). Up to the end of the season ten players had 100 or more centuries to their credit, J. B. Hobbs' total ) being the highest.

The highest recorded individual score in any match is A. E. J. Collins's 628 in a junior house match at Clifton in 1899, his innings of 6 hrs. 5o mins. being spread over five afternoons.

BIBLIOGRAPHY-I.

For scores, records, etc.: H. T. Waghorn, Cricket Bibliography-I. For scores, records, etc.: H. T. Waghorn, Cricket Scores, (1899) and The Dawn of Cricket (1906) ; Fred Lillywhite and the M.C.C., Scores and Biographies, 15 vols.; Fred Lillywhite, Guide to Cricketers (1849-1866) ; John Lilly white, Cricketers' Companion (1865—i885) ; James Lillywhite, Crick eters' Annual (1872--1900) ; John Wisden, Cricketer? Almanack (1864 to date) .II. For statistics, averages, aggregates 1878-1923: Sir Home Gordon, Cricket form at a glance (1924).

III. For Etymology, Origins and Earliest References: "H. P-T," Iii. For Etymology, Origins and Earliest References: "H. P-T," Cricket's Cradle, Early Cricket, Old-Time Cricket, Cricket's Prime.

IV. General History: H. S. Altham, A History of Cricket (1926), containing an extensive bibliography ; E. V. Lucas, The Hambledon Men (1907) , includes Nyren's work ; J. Pycroft, The Cricket Field (ed. Ashley-Cooper, 1922) ; Chronicles of Cricket (i888) ; C. Box, English Game of Cricket (1877) ; W. G. Grace, Cricket (1891) ; W. W. Read, Annals of Cricket (1896) ; K. S. Ranjitsinhji, Jubilee Book of Cricket (1897) ; Cricket ("Country Life" Library, 1903), admirably illus trated; P. F. Warner, Imperial Cricket (1912) ; Cricket ("Badminton Library," 1920) ; F. Gale, Echoes from old Cricket Fields (1896) .

V. Biographies: R. Daft, Kings of Cricket (1893) ; W. Caffyn, 71 not out (5899) ; A. Shaw, Alfred Shaw, Cricketer (1902) ; W. A. Bettes worth, The Walkers of Southgate (1900) ; Old Ebor, Talks with Old English Cricketers (1900) ; Memorial Biography of W. G. Grace (pro duced by the M.C.C., 1919) ; A. A. Lilley, Twenty-four Years of Cricket (1912) ; Lord Harris, A Few Short Runs (1921) ; P. F. Warner, Cricket Reminiscences (1920) and My Cricketing Life (1921) ; G. L. Jessop, A Cricketer's Log (1922); Lord Hawke, Recollections and Reminiscences (1924) ; G. Giffen, With Bat and Ball (1898) ; F. Iredale, Thirty-Three Years' Cricket (1923).

VI. Technical: Lambert's Cricketer's Guide 0816); N. Felix, Felix on the Bat (1845) ; the "Jubilee" and the "Badminton books" on Cricket (op. cit) ; C. B. Fry, Batsmanship (1912) ; G. W. Beldam and C. B. Fry, Great Batsmen (19o5) ; and Great Bowlers and Fieldsmen (1907) ; M. A. Noble, The Game's the Thing (1926) . The Fry and Beldam books consist of a magnificent collection of action photographs, acutely interpreted.

VII. County Histories: R. S. Holmes, History of Yorkshire County Vii. County Histories: R. S. Holmes, History of Yorkshire County Cricket, 1833-1903 (19o4) ; A. W. Pullin, History of Yorkshire County Cricket 1903-1923 (1924) ; F. S. Ashley-Cooper, Nottinghamshire Cricket and Cricketers (1923) ; Lord Alverstone and C. W. Alcock, History of Surrey Cricket (1902) ; W. J. Ford, Middlesex County Cricket Club, 1864-1900 (1900) ; F. S. Ashley-Cooper, Middlesex County Cricket Club, 1901-192o (1921) ; Lord Harris, History of Kent County Cricket (19o7), with Appendices 1910 and 1924; F. S. Ashley Cooper, Sussex Cricket Champions (1902) ; S. Santall, History of Warwickshire Cricket (1911) .

VIII. England v. Australia: W. Sparks, Test Cricket (1922, AppenViii. England v. Australia: W. Sparks, Test Cricket (1922, Appen- dix, 1925) , full statistics; P. F. Warner, How we recovered the Ashes 5903-4 (19o4) ; P. F. Warner, England v. Australia, 1911-12 (1912) ; M. A. Noble, Gilligan's Men (1925) ; P. F. Warner, Fight for the Ashes, 5926 (1926) ; M. A. Noble, Those Ashes (1927).

IX. Luckin, History of South African Cricket, 2 vols. (1914 and 1927).

X. University Cricket: A. C. M. Croome, Fifty Years of Sport at Oxford and Cambridge (1912) ; P. F. Warner and F. S. Ashley-Cooper, Oxford and Cambridge at the Wicket (1926) ; J. D. Betham, Oxford and Cambridge Cricket Scores and Biographies (1905) ; W. J. Ford, The Cambridge University Cricket Club, 182o-19o1 (1902). There is no history of the O.U.C.C.

XI. School Cricket: Fifty Years of Sport at Eton, Harrow and Win chester (1861-1921) ; F. S. Ashley-Cooper, Eton v. Harrow at the Wicket (1922) ; Sir Home Gordon, Eton v. Harrow at L rd's (1926) ; C. E. S. Mason, Winchester College Matches 1825-98; A. G. Guille mard, Rugby School Cricket Scores, R. W. Turnbull, Chel tenham College Cricket 1855-1900; E. L. Fox, Clifton College Cricket Records, 1863-1901 ; B. Ellis, Charterhouse Records, 1850-9o; A. H. J. Cochrane, Repton Cricket, 1866-1905; W. S. Patterson, Sixty Years of Uppingham Cricket (19o9).

XII. Miscellaneous: F. S. Ashley-Cooper, Lord's and the M.C.C. Xii. Miscellaneous: F. S. Ashley-Cooper, Lord's and the M.C.C. (192o) ; F. S. Ashley-Cooper, Cricket Highways and Byways (1927) ; F. S. Ashley-Cooper, Gentlemen v. Players (1900) ; P. Trevor, Lighter Side of Cricket (1901) ; Neville Cardus, A Cricketer's Book (1922); The best cricket novels are: H. G. Hutchinson, Peter Steele, the Crick eter (18q8) ; B. and C. B. Fry, ".4 Mother's Son" (1907) and J. C. Snaith, Willow, the King. The Cricketer, edited by P. F. Warner, appears weekly through the season. (H. S. A.)