Organization of the Cotton Industry

ORGANIZATION OF THE COTTON INDUSTRY The broad plan of this article is to study in detail the organiza tion of the cotton industry in Great Britain, since that is the most highly developed in the world, and then to pass on to consider how far the organization of industries in other countries shows variations from this.

The British Cotton Industry.

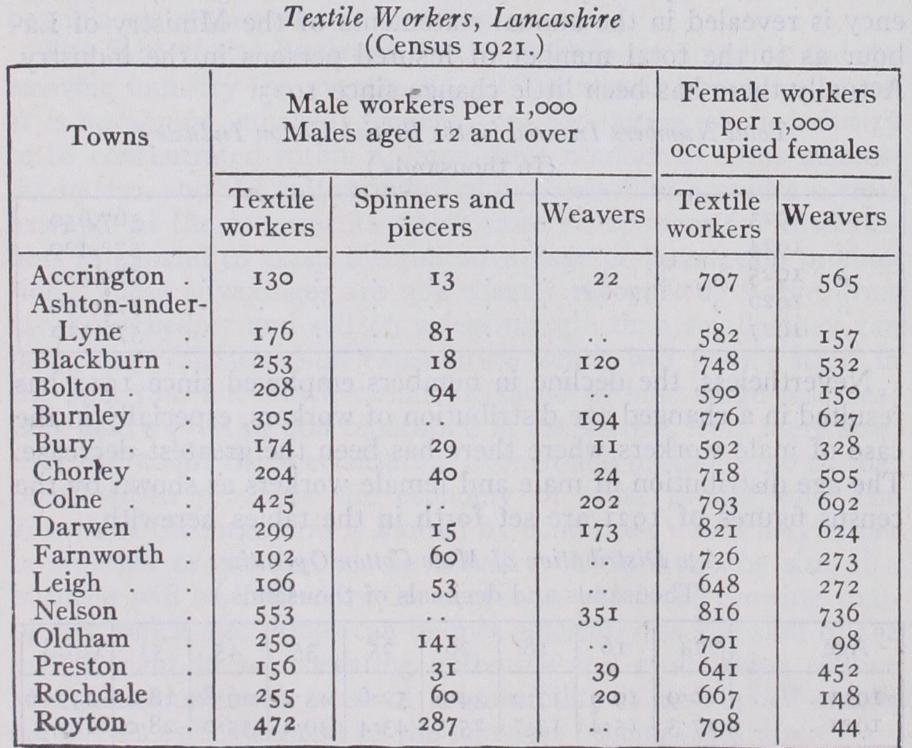

The cotton industry is con centrated almost wholly in Lancashire and the adjoining fringes of Cheshire and Derbyshire. But within the county itself there is further subdivision and specialization, since the processes of spinning and weaving are carried out in different areas and, within each area one finds the production of coarse goods and fine goods, each localized in its own special district. The spinning area is con centrated in the south-eastern part of the county, consisting of two contiguous areas, the smaller round Bolton and the larger round Oldham, connected by a number of small spinning towns. The weaving area lies immediately to the north of the spinning area, separated from it, but linked to it, by a number of towns doing both spinning and weaving. The weaving area also is sub divided into two groups of towns, one round Burnley and the other round Blackburn. Thus, the cotton industry is centred in the south-eastern quadrant of Lancashire, the main town lying on the fringe of the highland formed by a spur of the Pennines. The spinning towns lie on the southern and the weaving towns on the northern slopes of the moorland. The sharp distinction between spinning and weaving areas is disclosed by a table show ing the chief spinning and weaving towns.It will be seen that both Manchester and Liverpool are rela tively unimportant centres of production. They are the commer Chief Spinning Areas (Towns with outlying districts possessing more than a million spindles.) cial centres of the industry, whilst the spinning mills and weaving sheds are found in the smaller towns within the cotton area. Both the spinning and weaving areas are further divided rather sharply between the towns which produce coarse products and those engaged in the output of finer quality goods. Thus, on the spinning side, the Bolton district produces nearly the whole of the fine yarn made from Egyptian cotton, whilst the Oldham district confines itself largely to spinning coarser counts of yarn from American cotton. It is also possible to assign different parts of the weaving area to the production of different types of cloth. Nelson and Colne specialize in the weaving of fine cloth, particularly from dyed yarn. Burnley and Blackburn are interested in the weaving of coarse goods such as dhooties and sheetings for the Indian market. These distinctions must not be stressed too sharply, but they are sufficient to give to each town a special type of product and a peculiar dependence upon conditions in the market which takes these goods. It must not be supposed that this localized distribution of spinning and weaving is a fixed ar rangement. There has been some change within the last 5o years. There seems to have been a tendency for the proportion of spin dles and looms concentrated in the larger centres to decrease with proportionate advantage to the smaller centres. Moreover, the effect of the depression of ter the World War falling, as it did, unequally on different sections of the industry, may ultimately produce some redistribution.

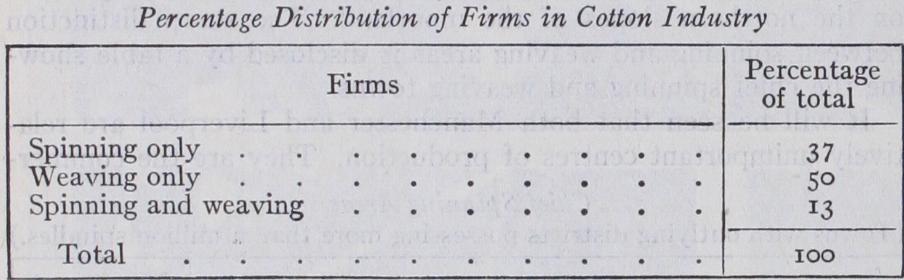

Another aspect of the specialization which must be regarded as characteristic of the industry is seen in the sharp distinction be tween spinning and weaving firms. As a general rule a firm con fines itself to spinning or to weaving, whilst the number of "com bined" firms, both spinning and weaving, is small. The following table, based upon the evidence given by the Manchester Chamber of Commerce before the Company Law Reform Committee, 1925, brings out this point clearly.

This natural stratification of the industry has had an important influence upon its history since the World War. The sharp cleav age between firms engaged in different processes has produced associations covering the different sections, but no association which would consider the interests of the industry as a whole. The result has been a lack of co-ordination, with each section con sidering the others guilty of unfair practice, and each anxious to exact the maximum return for its services without regard for the possible consequences to general interests.

The Size of the Business Unit.

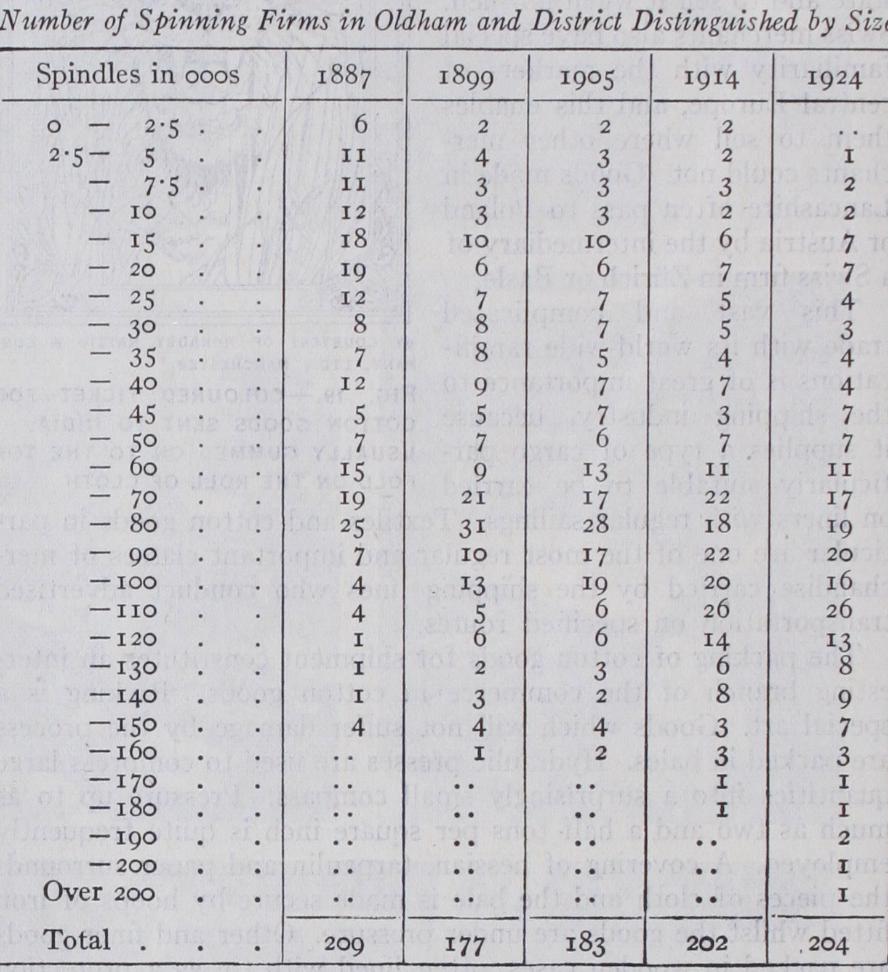

Both in the spinning and the weaving industry the average size of business is becoming larger. It is an almost universal tendency for the output of an industry to be concentrated within a diminishing number of firms increas ing in size, and the cotton industry in Lancashire provides a clear example of the movements which exist everywhere for the busi ness to expand to grasp the full advantage of large scale produc tion. These advantages are now clearly recognized. Large firms can buy cheaper and sell on a less margin than small; they can meet large initial capital expenditure which will justify itself in the long run, but which cannot be faced without large reserves; they gain a prestige and reputation in the market from mere size; they can adopt the specialization of men and machines up to that point which produces the economy of mass production. The growth of the large firm is limited by conditions which may either be internal or external to the industry. Ultimately the size of a business will be limited by the degree to which the growing com plexity which size brings can be met efficiently by the skill of the management in so delegating authority and establishing routine administration that a sense of responsibility is maintained among employees as the control of the manager becomes less direct.The purely productive concerns in the cotton industry shelve much of their commercial risk and thus facilitate the growth of large scale businesses. A spinner, through the use of the "futures" market and the purchase of cotton "on call," can move on to other shoulders the risks of price fluctuations in his raw material. He is not called upon to grant long credits on the yarn he has sold. The weaver also does not work to stock to any great extent; his commercial risks are taken by the shipping merchant, who gives a contract for the cloth to be woven and finances it during the finishing stages, giving the weaver prompt payment. The increase in size of the business unit is shown clearly in the results of an investigation made among the Oldham spinning firms by Mr. T. S. Ashton, of Manchester university.

In the table above, by the term "firm" is meant a business hav ing one or more mills in the same district. But it is obvious that, with the growth of large joint-stock companies, mills within the same business may be found in many parts of Lancashire. The extreme development of this widespread financial control is found in the appearance of combines among spinners.

No comparable figures classifying weaving establishments ac cording to size are available, but it can safely be generalized that the average weaving firm is smaller, measured by capital and la bour employed, than the average spinning firm, and that weaving firms have shown less tendency to concentration. The variety in the demand for cloth is greater than that for yarn, so that the weaving business must constantly face a market fluctuating as the tastes of consumers vary, whilst the spinner is less subject to this difficulty since the change of demand from one type of woven goods to another may leave the yarn required for the cloth exactly the same. Beyond this, however, the weaving firm, in its growth, attains the position of maximum technical efficiency much earlier than the spinning firm. The very large spinning firm has an appre ciable advantage over the small firm, but the large weaving firm has no such marked technical superiority over its smaller fel low. The difference between the size of spinning and weaving firms is due both to differing market conditions and varying factors of industrial technique.

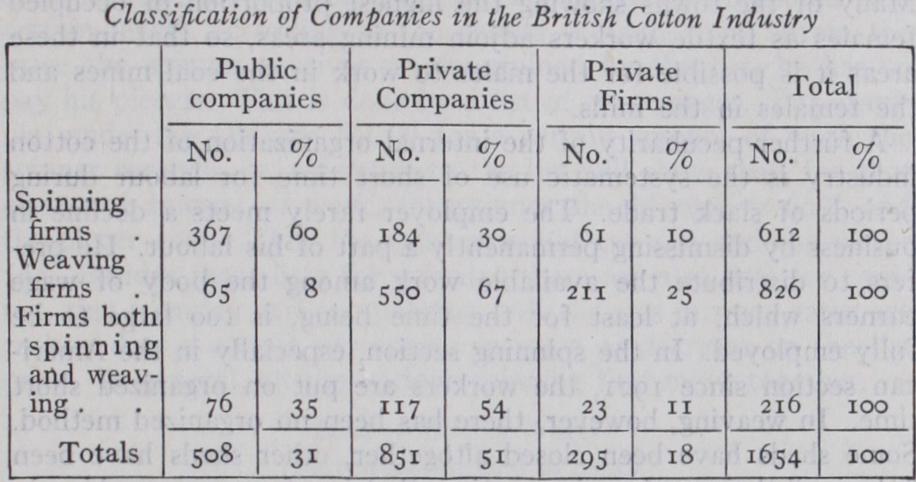

Methods of Capital Accumulation.—The spinning and weaving firms have always been financed locally to a large degree. The fact that there is no large issuing house in Manchester and that strong opposition always existed to the fusion of London and Manchester banks is proof of the financial isolation which has accompanied the geographical concentration of the industry. It is important here to distinguish between spinning and weaving firms. Most of the weaving firms are either private firms or pri vate companies; they can therefore make no public appeal for capital and they must find new capital through the personal sav ings of the owners or the investments of those who live in the dis trict and have a detailed knowledge of the prospects of each of such firms. The spinning firms, on the other hand, are, for the greater part, public joint-stock companies. This is brought out clearly by a table presented by the Manchester Chamber of Com merce to the Company Law Amendment Committee of 1925.

The normal pre-war method of financing a spinning mill was to combine small calls on share capital with loan money, a method of borrowing unique in British industry. Thus, before the World War, when a company was formed to erect or acquire a mill, a large amount of share capital was issued, but only a small propor tion—perhaps 5s. per Lr share—would be called up. The remain ing capital would be found through individuals depositing loans with the firm. Such loan money would bear interest at anything from 3-5% ; the lenders would have no security beyond that of ordinary creditors, so that the loans were not debentures; but withdrawal of loans could be made at short notice. It was nor mally the custom of the spinning firms to take loans up to the capital remaining unpaid on the shares so that unpaid share capi tal provided security to some degree for loans otherwise unse cured. The banks provided little accommodation, since the spin ner and weaver reduced their commercial commitments to a mini mum, rarely worked to stock save during depression and had small need of financial aid from outside bodies. This use of loan money is probably adopted from the early cotton factories, a num ber of which were co-operative undertakings but which changed into joint-stock companies. The early co-operators were not rich men and could only subscribe money in small amounts. To over come the difficulty of lack of capital it was necessary to borrow money on loan. These loans were of ten in large amounts, but the firms were willing also to accept smaller amounts. The success of this method of capitalization and the ease of borrowing in pros perous times appealed to other mills and especially to the new mills started in the booms of 189o, 1900, 1907 and 192o. • This method of raising capital has but few points in its favour and many against it. It may be argued that to grant facilities to the workers to use the firms in which they are engaged as sav ings banks with the same ease of investment and withdrawal will, to some extent, identify their point of view with that of the em ployers and tone down the naturally sharp cleavage of interest between the two groups. And in the past, it has been refreshing to find that confidence between masters and men which the small size of business in the Lancashire cotton industry long retained and which necessarily preceded the widespread growth of loans. But the loan system finds few supporters, since the post-war de pression clearly revealed its limitations. It is undesirable for the worker to find employment and invest his slight capital in the same business or industry, and the cotton operative after 1921 often found his savings and his employment disappearing together.

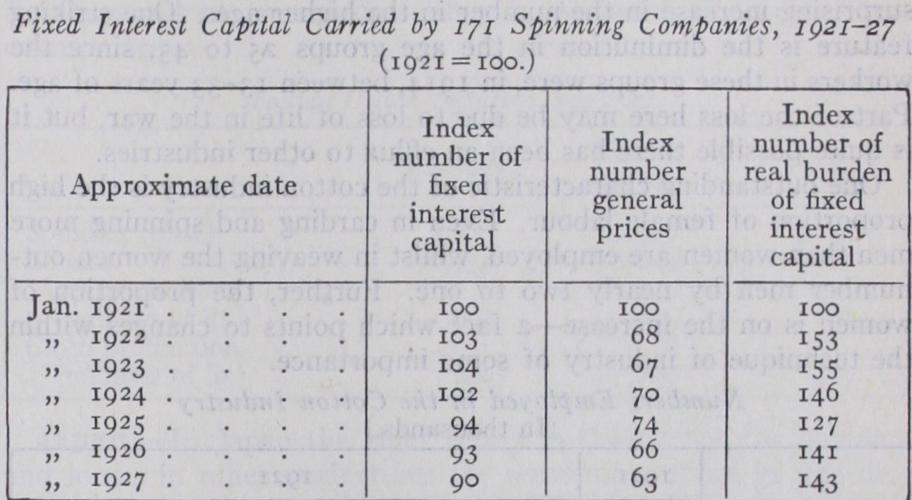

Businesses which have a large proportion of capital in forms upon which fixed interest must be paid are peculiarly susceptible to movements in general price levels. A fall in price increases the real burden of the fixed money sums which are to be paid in inter est ; a rise in price creates a corresponding advantage, but it also encourages the business reaping the advantage to capitalize and often over-capitalize this gain. Thus although, taking Jan. 1921 as a base (= r oo), the total fixed interest capital of 171 spinning companies had fallen to 90 in Jan. 1927, yet, by making allowance for price changes in the interim the real burden of the interest charges had risen from r oo to 143. The following table shows this.

The existence of large sums of loan money robs a business of the power to meet depression by a cutting of costs until the con sequent fall in prices re-establishes the volume of demand. People will lend freely when trade is good. When trade is bad the loan holders may either leave their capital with the company, in which case interest has to be paid upon it whether profits are being made or not ; or they may withdraw their loans, in which case the com pany is still more embarrassed by having to find ready funds to repay the loans. So long, however, as immediate resources for this repayment could be found by calls upon shareholders, the corn pany would still remain solvent. But even this safeguard was ig nored during the post-war boom when debentures and other mort gages more than covered the uncalled capital and the loanholders were left quite defenceless.

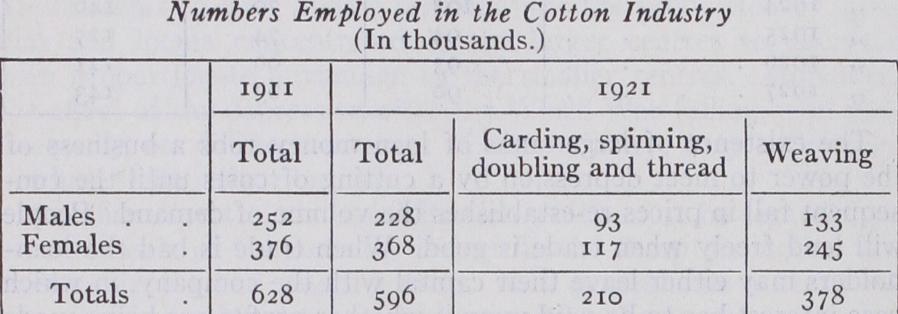

Labour.—In 1921 there were 596,00o men and women in the cotton industry of Great Britain. Thus, in numbers employed, the cotton industry is only half the size of the coal industry, but more than twice the size of the woollen industry. By com parison of the census figures of 1911 and 1921 a decrease of 32,00o workers, mostly men, is shown in the industry. This de cline is partly due to the loss of male labour and the decrease in the number of new entrants during the war, and the increased use of female labour, either to replace absent men or to meet the con ditions following the increased use of the ring spindle. The depres sion after 1921 probably caused some reduction in the total num bers engaged in the industry. Although no figures are obtainable which are directly comparable with the census figures, the tend ency is revealed in the annual statements of the Ministry of La bour as to the total number of insured persons in the industry. Actually there has been little change since 1923.

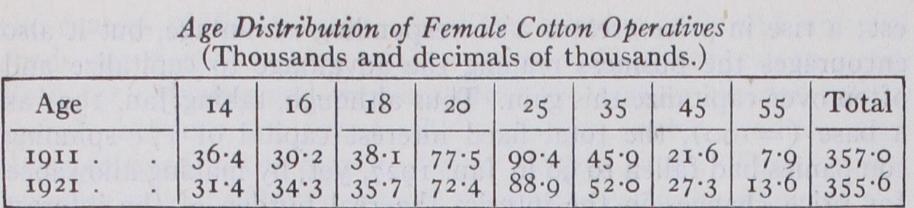

Nevertheless, the decline in numbers employed since 19 r 1 has resulted in a changed age distribution of workers, especially in the case of male workers where there has been the greatest decrease. The age distribution of male and female workers as shown by the census figures of r021 are set forth in the tables herewith_ The effect of the general decline in numbers is evidenced by the decrease in the age groups below 25, but there has been a rather surprising increase in the number in the higher ages. One striking feature is the diminution in the age groups 25 to 45, since the workers in these groups were, in 1914, between 13-33 years of age. Part of the loss here may be due to loss of life in the war, but it is quite possible there has been an efflux to other industries.

One outstanding characteristic of the cotton industry is the high proportion of female labour. Even in carding and spinning more men than women are employed, whilst in weaving the women out number men by nearly two to one. Further, the proportion of women is on the increase—a fact which points to changes within the technique of industry of some importance.

Although the county of Lancashire has within its borders prac tically the whole of the British cotton industry, it must not be presumed that Lancashire is entirely dependent on the cotton in dustry. In point of fact, less than 1 o% of the male workers in the county are engaged in the industry, while the metal industry, on the other hand, has 12% of the male workers. For females, how ever, the importance of textile occupation is predominating, one third of the occupied females being thus engaged.

A glance, however, at the distribution of the operatives over the county shows that the majority of the spinners live in the towns in the south-east corner of the county round Bolton and Oldham. The majority of the weavers are grouped round Burnley and Blackburn. The textile occupations are, however, particularly associated with the smaller towns. The proportion of textile workers in certain areas is shown in the table below. Textile workers may include some wool operatives, but, broadly, textile workers here may be taken as cotton workers. It should be noted that the table below gives the predominant class of occupation in each case, not the absolute importance, since 2o% of the work ers in one area may mean a greater actual number than 3o% in another.

Weaving is so largely a woman's occupation that even in such distinctive spinning towns as Oldham and Bolton, female weavers outnumber female spinners and piecers; in Bolton by almost four to one. It is natural, therefore, that it should be in the weaving areas that the largest proportion of occupied females are em ployed as textile workers. One further fact should be noticed. Female textile workers are not so much concentrated in the smaller towns as in the case of male, while, in certain areas, es pecially in the coalfields, they are found in large numbers. There is a special association between mining and textile manufacture. Many of the towns showing the highest proportion of occupied females as textile workers adjoin mining areas, so that in these areas it is possible for the males to work in the coal mines and the females in the mills.

A further peculiarity of the internal organization of the cotton industry is the systematic use of short time for labour during periods of slack trade. The employer rarely meets a decline in business by dismissing permanently a part of his labour. He pre fers to distribute the available work among the body of wage earners which, at least for the time being, is too large to be fully employed. In the spinning section, especially in the Ameri can section since 1921, the workers are put on organized short time. In weaving, however, there has been no organized method. Some sheds have been closed altogether, other sheds have been "playing" their workers in rotation, that is, of 12 men working in a weaving shed, each man is unemployed for one week every 12 weeks. In other mills, workers have been only working three in stead of the usual four looms.

Such a method is probably justifiable where the depression is temporary, but it becomes dangerous when trade permanently declines, since it impedes that flow of labour from the industry necessary to re-establish a normal level between the supply and demand for employees. Labour in the cotton industry is naturally immobile. That is due, among other factors, to the high pro portion of women workers ; to the long association of special workers to special firms and to the long experience which an op erative must have before he will be put in charge of a set of mule spindles. The system of short time working, therefore, in tensifies the difficulty which the industry has in ridding itself of surplus labour.

Wages and Trade Unions.

Trade unionism is strong among the workers in the cotton industry. No accurate figure can be given of the total number of members of trade unions, but the Ministry of Labour statistics show that at least 65% of the workers are in unions. Almost all the spinners are members of either the Amalgamated Society of Operative Cotton Spinners and Twiners, created in 1853, or the Amalgamated Association of Card Blowing and Ring Room Operatives which was founded in 1886. The former body is divided up into 18 districts and five provinces of which the Oldham province is probably the most important, controlling 8,000 spinners and 6,75o piecers. Piecers are not organized into separate unions, but are admitted as mem bers of piecers' associations controlled by the spinners' unions. Trade unionism is not so strong or so centralized in weaving, principally because the majority of weavers are women. The overlookers are joined together in the General Union of Asso ciations of Loom Overlookers, founded in 1884, whilst the general body of weavers are organized into the Northern Counties Amal gamated Association of Weavers, into which weavers' assistants are admitted as members. Besides these big unions there is a number of smaller craft unions.No attempt is made to bind all the cotton operatives into one close union. The United Textile Factory Workers' Association, which comprises nine amalgamations of cotton trade unions and represents 300,00o members, is only periodically called to con sider such questions as factory legislation.

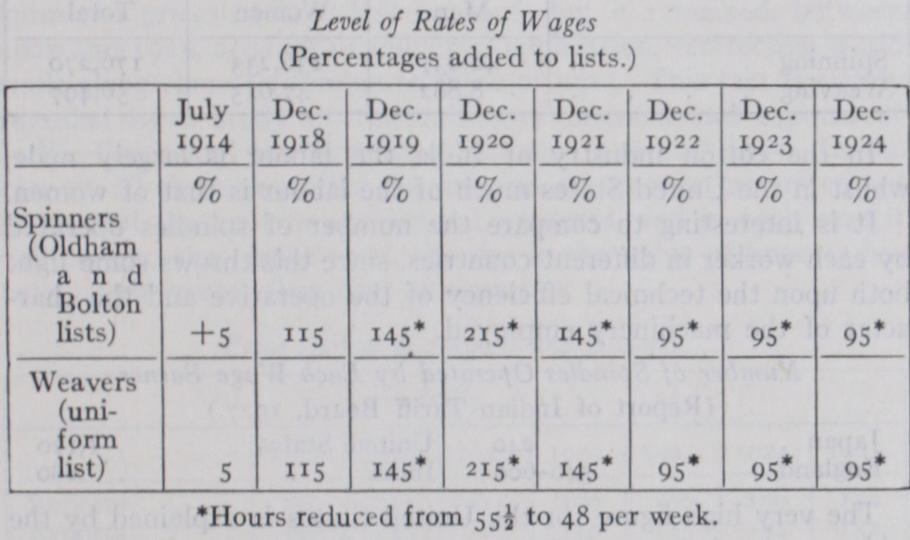

Wages paid for spinning yarn or weaving cloth are, in most cases, paid according to the piece price lists. These lists are tabu lated statements giving the details of payment to the operative for each class of work done according to output. They date from the beginning of the 19th century and have been revised from time to time, but they retain in principle their original form.

They are statements of the method of payment to the worker according to the amount of his production.

In the spinning section, wages are governed by various lists, the chief of which are the Oldham and Bolton lists. There are other lists in use in Ashton-under-Lyne, Preston, Burnley and Blackburn. The Bolton list was first prepared in 1858 and the Oldham list in 1876. The difference between the two is that while, under the Oldham list, payment is made on the number of hanks on the length of yarn spun, under the Bolton list payment is made on the weight of yarn spun. Actually there is little differ ence between the two, since the given weight of yarn should be a certain length according to the counts of yarn spun. From the price the spinner receives as determined by the list, he has to pay his piecers. This is done by a list of percentages. For exam ple, under the Oldham list, if for a certain amount of work the spinner receives f2, reference to the list will show that, for that class and amount of work, the spinner should receive 6o% and the piecer 40%. Thus the spinner would get 24s. and the piecer 16s. Besides these lists for spinning there are also lists for card ing, ring spinning and cop packing. All changes in wage rates are reckoned as a certain percentage increase or decrease on the list price. In general, all the various spinning lists move together.

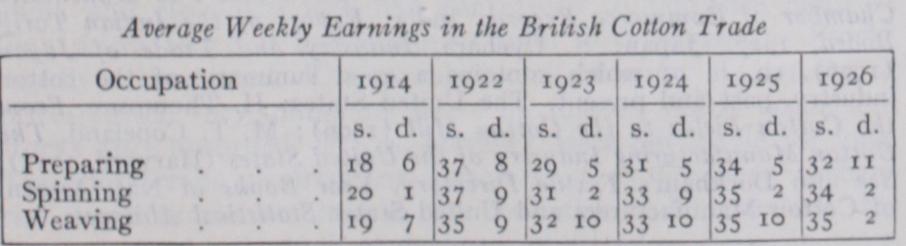

In weaving, although there are many lists governing the vari ous classes of work, there is one general list known as the uniform list for plain goods which was adopted in 1892 and now serves as a standard for the building up of smaller lists for fancy and coloured goods. The introduction of the use of artificial silk, while it did not affect spinning, caused trouble in weaving. A tern porary arrangement was made at first granting extra payment to operatives weaving artificial silk, but later a separate list was made. After 18 months' negotiation the list was finally adopted in Oct. 1925. These lists do not give a clear idea of the actual earnings of cotton operatives at any particular time. The only information as to variation in actual earnings is that collected by the Ministry of Labour. Each month they obtain from employers particulars of the total number of wage earners and total wages paid to those workers. The number of returns, however, are perhaps too small to be very accurate, but they give an index of actual earnings.

The figures include the effect of short time, overtime and piece work and are for the month of June each year except for 1926, where, to avoid the effect of the general strike, the figure for the month of April is used. The special enquiry of the Ministry of Labour in 1924, which covered 75% of the workers, showed that average weekly earnings for all workpeople was 36s. zod., for men 475. and for women 28s. 3d.

Internal Organization in Other Countries.—There is a striking difference between the internal structure of the Lanca shire cotton industry as it has already been outlined and that of many of the other important cotton industries in the world. The first and most noticeable dissimilarity is that whereas the bulk of the spindles and looms in Great Britain are concentrated within a short radius of Manchester, in other countries no such localiza tion exists, and the industry is either scattered thinly over large areas or concentrated at several points geographically remote.

India.—Thus in India nearly half the industry is found in Bombay and the remainder either in Ahmedabad or other up country areas.

Japan.—In Japan the chief centre is Osaka, but the spindles and looms in other prefectures far outnumber those in this dis trict. The distribution of spindles and looms in Japan is changing rapidly.

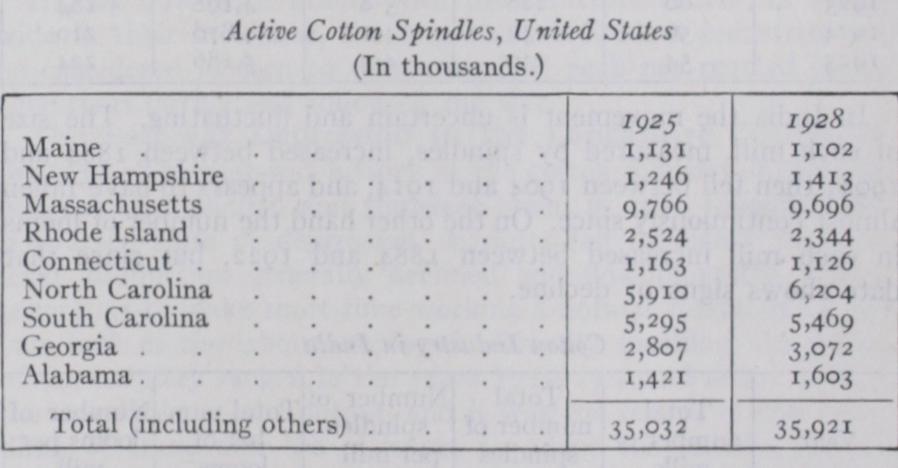

United States.—In the United States the industry is found almost equally divided between the New England and the cotton growing States of the South (April, 1928, New England 44%; cotton-growing States, 51% ; others 5%), though the tendency is for the development of the latter at the expense of the former. In the North, Massachusetts contains more than half the spindles, whilst in the South, North and South Carolina are the points of concentration. The numbers of spindles in the States possessing more than a million are shown below.

An even more significant difference between Lancashire and most other countries is that the specialization of business upon single processes is almost peculiar to the former. In India, Japan, America, Germany and Italy spinning and weaving are largely carried on by one firm. The reasons why the newer industries should in this way have adopted a form of industrial organiza tion quite distinct from that adopted in Great Britain are not apparent. It may be that the tremendous production in Lan cashire and the partial monopoly which was thus created made possible a form of specialization which the smaller scale of pro duction in other countries has not yet justified. Moreover, since ring spinning is the common method in countries other than Great Britain the combination of spinning and weaving saves heavy transport charges. On the ring-frame the yarn must be wound on wooden bobbins, whilst with the mule-frame it may be wound either on paper tubes or even on the bare spindle. The transport of ring-frame yarn would involve the payment of freight charges on these heavy wooden bobbins. Combined firms save this cost. Moreover, the advantages of specialization only be come apparent when an industry is so highly localized that the transfer of semi-finished products from one firm to another can be easily and cheaply effected. Where the businesses in the indus try are widespread then each business will be tempted to take up spinning and weaving, both to guarantee itself a supply of yarn for weaving or a market for its yarn, and to save transport costs which would be incurred in buying yarn elsewhere. But the sys tem in Lancashire has often been called into question, and the difference between it and that of many other countries explained on the ground that new industries are adopting methods of effi ciency which Lancashire producers have been regrettably tardy in imitating. Certainly the system of extreme specialization has its drawbacks. It involves the constant movement of the product, in its progress towards the finished state, from one set of hands to another, thus making the period of production longer and swelling the cost of production by transport charges. It creates beyond this the need for a large group of middlemen between stages, whose commissions increase the final cost. It has produced a horizontal organization of the industry with each section at tempting to extract from the final price the highest possible figure for itself.

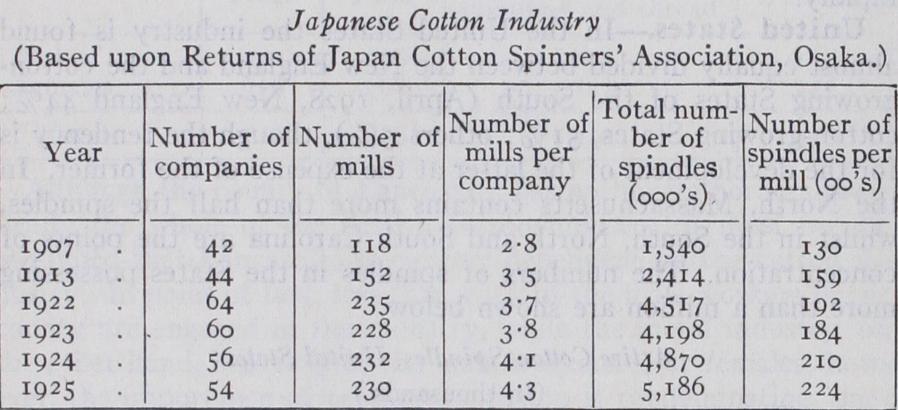

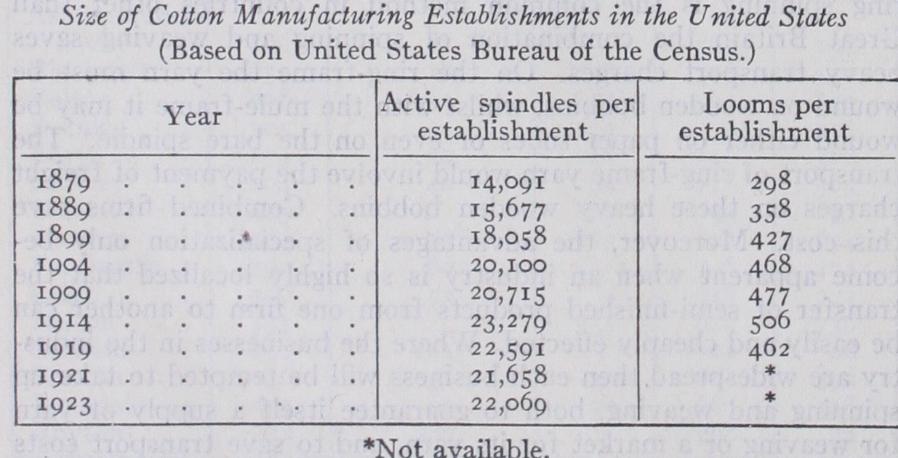

The study of changes in the average size of the individual busi ness discloses interesting international diversities. It has already been pointed out that in Lancashire the large business is absorb ing an increasing proportion of the trade. This movement has its counterpart in Japan, where the numbers of spindles per estab lishment has increased and the number of establishments con trolled by each company risen. It is apparent, therefore, that technical development and financial concentration are going hand in hand.

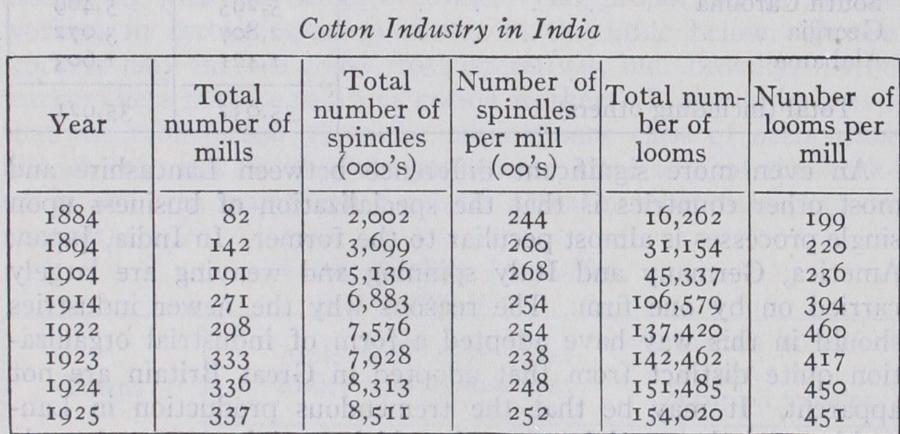

In India the movement is uncertain and fluctuating. The size of each mill, measured by spindles, increased between 1884 and 1904 ; then fell between 1904 and 1914, and appears to have fallen almost continuously since. On the other hand the number of looms in each mill increased between 1884 and 1922, but since that date shows signs of decline.

In the United States the same tendency towards a decline in average size has existed since 1914.

The cause of this setback in both India and the United States appears to be the same. In both countries the development of the industry is taking the form, not of growth around the old and well established centre, but of the appearance of mills in fresh areas. Naturally the new mills thus springing up are, on the whole, smaller than those which have had opportunity to grow to maturity elsewhere. Thus, in India, the mills of Ahmedabad are smaller than those in Bombay and the mills of the cotton-growing States of the United States smaller than those of the New Eng land States. But this condition is probably temporary. With time, youthful firms attain the size of maturity and gradually we may expect the disappearance of the purely transient factors which have operated in these two countries and the re-establishment of the inevitable movement towards large scale, both in spinning and weaving.

Labour conditions also vary from country to country. The high proportion of women workers in Lancashire has already been pointed out. In Japan the importance of female labour is much greater still, since over the whole of the industry more than three women are employed to each man.

In the cotton industry of India the labour is largely male, whilst in the United States much of the labour is that of women.

It is interesting to compare the number of spindles operated by each worker in different countries, since this throws some light both upon the technical efficiency of the operative and the char acter of the machinery employed.

Number of Spindles Operated by Each Wage Earner (Report of Indian Tariff Board, 1927.) Japan . . . . 240 United States . . . 1,120 England . • • 540-60o India . . . . i8o The very high figure for the United States is explained by the widespread existence of ring spinning, which makes less demand upon the spinner than the mule spindle found largely in England. The high figure for Japan suggests that the labour in the former country is more competent industrially than in India and that Japan is steadily building up a permanent and skilled population of textile workers. The disparity between the Western and the Eastern countries is very great and largely offsets the difference in wage levels to which reference is so often made.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Great

Britain: Sir S. J. Chapman, The Lancashire Bibliography.-Great Britain: Sir S. J. Chapman, The Lancashire Cotton Industry (Manchester, 1904) ; Final Report of the First Census of Production in the United Kingdom, 1907 (1913) ; Sir S. J. Chapman and T. S. Ashton, "The Sizes of Businesses mainly in the Textile Industry," Journ. Royal Statis. Soc. 0914); Census of Population of United Kingdom, 1921 (Lancs. vol., 1923) ; G. W. Daniels and J. Jewkes, "The Crisis in the Lancashire Cotton Industry," Econ. Journ. (1927), and "The Comparative Position of the Lancashire Industry and Trade," Manchester Statis. Soc. (1927) ; Final Report of the Third Census of Production in the United Kingdom, 1924 (1927) ; Committee on Industry and Trade, Survey of Textile Indus tries (1928) . See also The Cotton Year Book and The Manchester Chamber of Commerce Record. India: Report of the Indian Tariff Board, 1927. Japan: S. Uyehara, Industry and Trade of Japan (1926), ch. ii. of which contains a good summary of the cotton industry, past and present. The United States: H. Thompson, From the Cotton Fields to the Cotton Mill (1906) ; M. T. Copeland, The Cotton Manufacturing Industry of the United States (Harvard, 1912). See also Dockham's Textile Directory, Year Books of Nat. Assocn. of Cotton Manufacturers and United States Statistical Abstracts.The outstanding result of the World War was to reduce the demand for the cotton goods of Lancashire and to apply a stim ulus to the textile industries of the East and the United States of America in such a way that the centre of gravity in matters textile moved away from the United Kingdom. All war sets up stresses in the finely adjusted economic system built up slowly in times of peace. The World War was particularly destructive of the conditions demanded for free and ample international trad ing. The cotton trade feels the worst effect of such dislocation ' since, for the most part, the raw material is grown in one group of countries and manufactured into fabric in another. The war produced the national antagonism of peoples previously engaged in lucrative commerce ; it temporarily swept away the credit facilities ; it weakened transport and communications for many years; it impoverished whole nations, bringing them to the state that, having nothing to sell, they could buy nothing; it produced a crop of small nations all anxious to encourage native industry and exhibit their new-found sovereignty by the erection of tariff barriers inimical to the highest general prosperity.

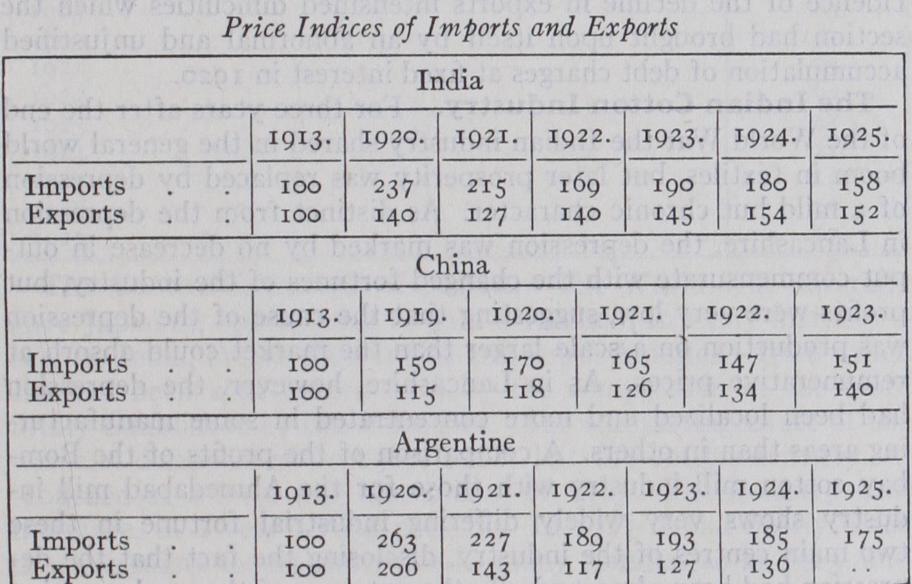

The political results of the war were not, however, so perma nent nor so deep-rooted as certain economic consequences. After the war there was a very marked tendency for the price of manu factured goods in the world to become dearer in relation to agri cultural products. The result was that a given unit of manufac tured goods commanded a larger unit of agricultural commodi ties than it could have commanded in 1913. This produced in the Eastern races—largely engaged in agriculture and consuming vast quantities of machine-made cotton cloth—a considerable decline in purchasing power and a falling off in the quality of the cotton cloth bought. The divergence between world agricultural and industrial prices became less by 1928, but it remained, between 1920 and 1925, a factor of universal application, redirecting world trade along channels foreign to those of 1913. This fact is clearly revealed by a study of the values of imports and exports of India, China and the Argentine between 1913 and 1925. In the case of all three countries the imports are largely manufactured goods and the exports agricultural products, and in each case it will be seen that, since 1913, the rise in the value of imports has been much greater than that of exports.

The post-war period had been one of sudden and abnormal fluctuations in prices. In 192o there was an almost world-wide boom in textiles, a feverish and unhealthy prosperity of industries engaged in meeting wants which had remained unsatisfied during the war. The prices of cotton, yarn and cloth rose to amazing heights. The bubble soon burst. Prices fell rapidly. Dealers in India and elsewhere who had contracted to purchase cloth at high prices found it impossible to fulfil their contracts. Stocks rapidly accumulated. The cumulative effect was a violent sag of prices to the very minimum where liquidation slowly began and stocks were absorbed. Prices, however, were not stable for long. The short crops of American cotton 1922-24 produced a sharp rise in prices and resulted in the confusion and loss which this produces among the bulk of dealers and manufacturers. In 1925, when the cotton world had accustomed itself to the high plateau of prices of the three previous seasons, the American crop reached i 8,000,000 bales and prices again fell considerably to below i s. per lb. and continued low in 1926 and 1927. The effect of these constant oscillations was to make all sections of the cotton indus try chary of holding large stocks. In Japan, where organized marketing and the use of "hedges" are not yet highly developed, the spinner must hold large supplies of cotton to meet his require ments for the following three to six months, and the fall in prices after 1925 shook many firms severely. Dealers, either wholesale or local, will always try to avoid the accumulation of large stocks when there is the possibility that prices may fall rapidly and leave them with a dead loss. The post-war textile market was one of hand-to-mouth buying and selling. The confidence of the markets was shaken by a series of unfortunate events ; there was a reluc tance to engage in long term commitments. This development had both its advantageous and its undesirable side. Large stocks are apt, during a period of depression, to clog the market and delay recovery. But without substantial stocks a market can never have the stability and general confidence which these stocks engender. Whilst merchants and dealers prefer to give small orders at frequent intervals rather than large orders for bulk output, the spinner and weaver must also be engaged fitfully, spasmodically and, therefore, in a manner which prevents his gaining the economies which come from constant running of plant in a well established routine manner. Such were the conditions in I92o-27.

The World War does not appear, however, to have reduced the volume of the consumption of cotton cloth in the world. Habits of consumption change only slowly and continually tend to re assert themselves. The decreased purchasing power of the Eastern nations has, apparently, reflected itself to a greater degree in the consumption of coarser goods than in the decline of the total amount of cloth used. Estimates on this point can only be rough, but the two investigations which have been made (Memorandum on Cotton—International Economic Conference, Geneva, 1927, and The Comparative Position of Lancashire Industry and Trade, by G. W. Daniels and J. Jewkes) on this point reach the same general conclusion that the outstanding fact in the post-war textile world—the decline of the Lancashire cotton industry—cannot be explained by any shrinkage of the world consumption of cotton cloth.

Having now dealt briefly with those factors which are world wide in their incidence, the important individual industries will be considered in turn to determine how each has reacted to the conditions during and following the war.

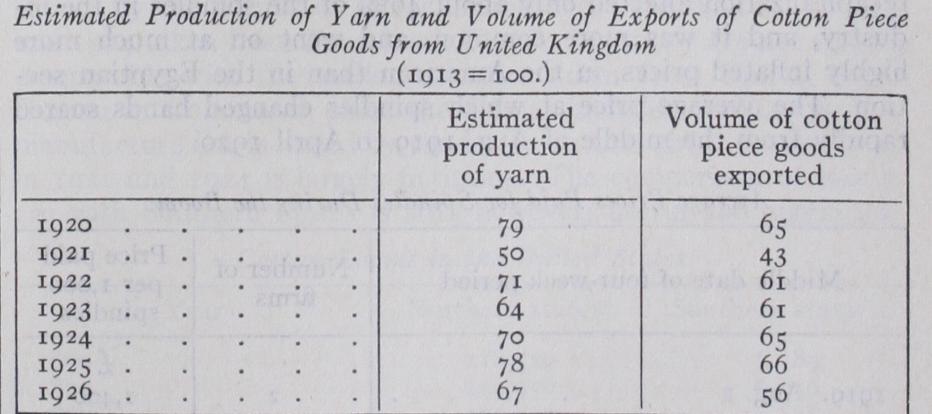

The Post-war Depression in the Lancashire Cotton In. dustry.—The post-war history of the cotton industry in England was one of a sudden and transient boom in 192o followed by a protracted state of depression. Exports fell far below the 1913 level, production generally declined and unemployment was so general as to make short-time working a normal condition for the vast bulk of the labour employed. Broadly speaking, the output of the industry ranged in the years r 921-2 7 round about 70% of the standard pre-war output, and it was the results of this dwin dling of trade and the attempts to adapt the industry to the reduced demand which constituted the significance of the period. The table below shows the decline in both exports of cotton piece goods and production of yarn within the industry.

The depression was not felt equally in every section of the in dustry. It was localized in a manner determined by circumstances both internal and external. The decline in Lancashire's markets for cotton goods was more marked in the case of countries taking the coarser and cheaper kinds of cloth than in that of countries which consumed the finer and more expensive products. The re action of this was to concentrate the worst effects of the depres sion in those areas where the coarse materials were largely turned out. Thus, on the spinning side, districts such as Oldham and Royton which produced the low counts of yarn showed greater unemployment and a larger decline in trade than areas such as Bolton and Leigh, which were, and are, engaged in spinning the long staple Egyptian cotton from which the specialties are pro duced. The same difference of industrial experience according to the quality of output is to be found on the weaving side, where areas such as Colne and Nelson showed a higher general prosperity between 1921 and 1927 than Blackburn, Darwen or Accrington, where the bulk products for low Indian demand were woven. The finishing trades in the Lancashire industry have avoided the losses of the spinners and weavers since the trusts have been able to avert the competition for a reduced volume of trade, and, by the establishment of minimum prices, to make large annual profits throughout the whole of the depression.

The cause of the excessive dwindling of the export markets for coarse goods was the existence of foreign competition. The production of the finer types of cotton cloth demands a high degree of technical knowledge on the part of directors and man agers and an advanced state of industrial application and manual dexterity on the part of employees. Neither was likely to exist in the new textile industries which have taken trade from Lanca shire. Their competition, therefore, confined itself largely to the less expensive end of the range of textile products and in this they gained the advantage from the use of the most modern automatic machinery, which, whilst unsuited for a production of finer cloths, made few demands upon the intelligence of the operatives and was well adapted for turning out standard bulk lines at prices lowered by the use of mass production methods.

One or two transient factors operated on occasions after 1920 to impede the recovery of an industry whose difficulties were caused by other and more fundamental conditions. The policy of deflation, adopted between 1921 and 1924, naturally harassed exports whilst it was in process, and the sudden resumption of the gold standard appears to have caused a sharp, if temporary, re duction in exports and employment. The high price of American cotton in the seasons 1921-24, due to abnormally low crops, pre vented the fall in the cost of production that had necessarily to precede any enlargement of demand. Both these factors had dis appeared by 1927 and yet the fundamental maladjustment of the industry to the changed conditions of the post-war economic sys tem prevented even a distant approach to conditions of prosperity.

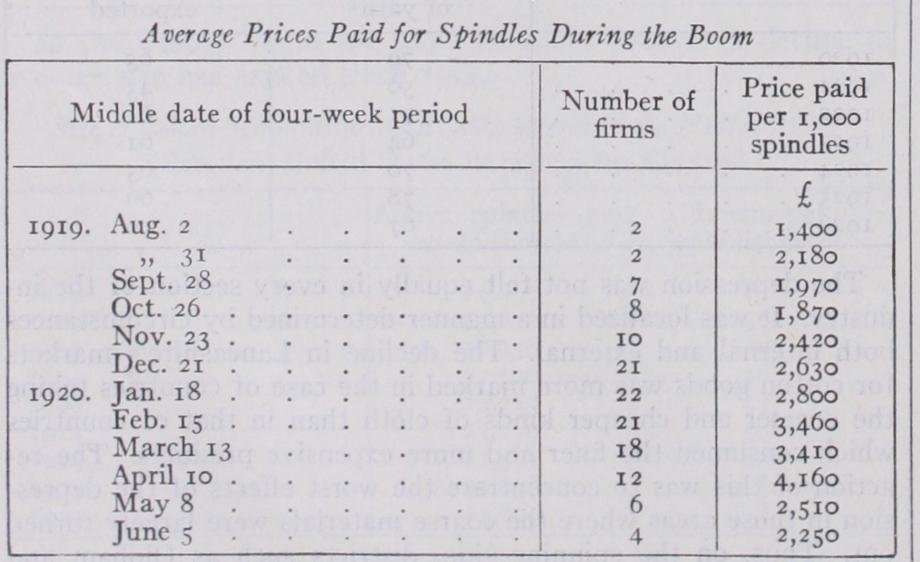

Apart from questions of technical efficiency, the greatest hin drance to the forcing down of cost of production which might have enabled the industry in Great Britain to restore or main tain its position, was the existence, in the spinning industry, of a heavy debt burden of debentures, loans and bank overdrafts upon which interest had to be paid which, in turn, was placed upon the selling price. That burden was largely created during the boom in cotton in 1919 and 1920, when spinning mills fre quently and rapidly changed hands at highly inflated prices. This recapitalization affected only about 46% of the spindles in the in dustry, and it was more common, and went on at much more highly inflated prices, in the American than in the Egyptian sec tion. The average price at which spindles changed hands soared rapidly from the middle of Aug. 1919 to April 1920.

But the dangers of this abnormally swollen capitalization of a large proportion of the spindles in the American spinning sec tion were not to be found so much in the transfer of spindles at heightened prices as in the method, which was general during the boom, of raising but a small proportion of the purchase price by capital actually paid up, and leaving the remainder to be found either by the issue of debentures, the invitation for the deposit of loans or the use of bank overdrafts. Taking a sample of 129 important spinning companies which underwent reconstruction nearly half the purchase price was left to be raised in this way.

Financial Reconstruction of 129 Spinning Companies in Lancashire Cotton Industry Total Purchase Price . . . . . . . . 38,257,000 Paid-up Share Capital plus Premiums paid on Shares . 21,372,000 Total Amount to be raised by loans, bank overdrafts and debentures . L16,885,000 When the boom broke, as suddenly as it had arisen, the recon stituted companies found themselves faced with these existing debt burdens which became more onerous with the fall in the price level. The interest charges on these debts made a necessary and inescapable addition to the cost of production. In order to meet these heavy and constantly recurring demands for the pay ment of interest on fixed interest securities, spinning companies resorted to selling of yarn at prices which, while unremunerative, supplied immediate funds for this purpose. The result was wide spread depression, for which the only remedy appeared to be a decline in the cost of production stimulating demand and provid ing full-time for spindles reduced to an economic capital basis.

The depression in Lancashire between 1920-2 7 was, therefore, a depression of the American section of trade. The peculiar in cidence of the decline in exports intensified difficulties which the section had brought upon itself by an abnormal and unjustified accumulation of debt charges at fixed interest in 1920.

The Indian Cotton Industry.

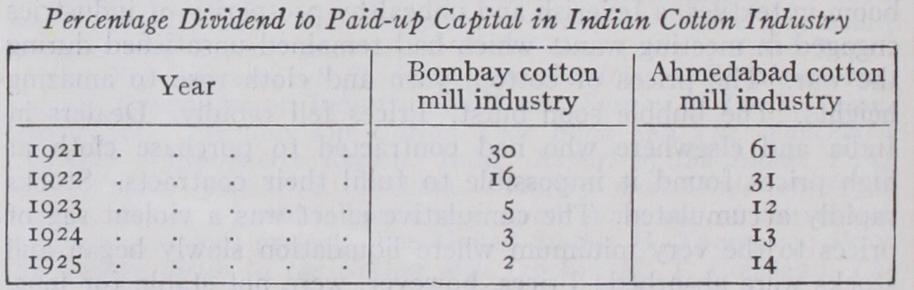

For three years after the end of the World War the Indian industry shared in the general world boom in textiles, but later prosperity was replaced by depression of a mild but chronic character. As distinct from the depression in Lancashire, the depression was marked by no decrease in out put commensurate with the changed fortunes of the industry, but profits were very low, suggesting that the cause of the depression was production on a scale larger than the market could absorb at remunerative prices. As in Lancashire, however, the depression had been localized and more concentrated in some manufactur ing areas than in others. A comparison of the profits of the Bom bay cotton mill industry with those for the Ahmedabad mill in dustry shows very widely differing industrial fortune in these two main centres of the industry, disclosing the fact that the de pression had been almost wholly the outcome of the weak position of the Bombay mills since 1921, due, according to the Tariff Report of 1927, to over-investment in the boom period.

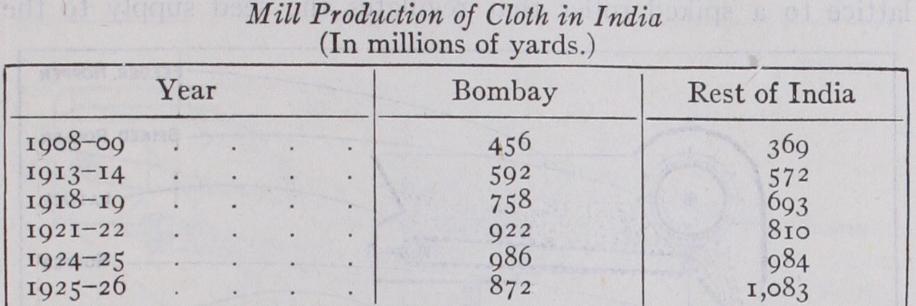

The varying prosperity of the two sections of the industry since 1920 was but a special case of the general movement for cotton manufacture to move from Bombay to Ahmedabad or other up country centres. That change was beginning to take place be fore the war, but it was hurried on by war conditions and the post-war boom. The reason for this industrial shift was the lower cost of production at which yarn and cloth could be made in the centres outside Bombay. In particular, wage costs were much lower in the up-country centres than in the Bombay district, where labour was beginning to demand a higher standard of living than is customary in other parts of the country. The cost of fuel and power was higher in Bombay than in Ahmedabad, as were the charges for water and local taxation. The cost of raw material and the advantages to be gained from proximity to markets prob ably showed little difference when comparing the two centres, but the high labour costs in Bombay were sufficient to turn the scale to its disadvantage. The changes in the importance of the two sections are shown in detail below.

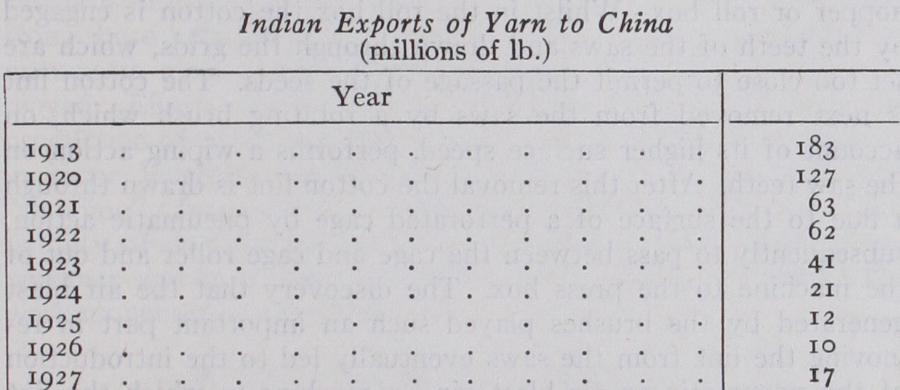

Af ter the end of the war the Indian industry, and particularly the Bombay section, felt seriously the effect of the development of the cotton mill industry in China. Bef ore the war the exports of yarn from India to China ranged between i 5o and 200 million lb. But the growth of spindles in China from about 5oo,000 in 1913 to over 3,000,00o in 1925, combined with the increased com petition of Japan in that market, caused a remarkable, and prob ably permanent, decrease in these exports. Much of that yarn was exported from the Bombay industry and with its decline dis appeared one of the methods by which the overhead costs of that industry were formerly spread thinly over a large production. The decline is shown in the table.

The Cotton Industry of Japan.

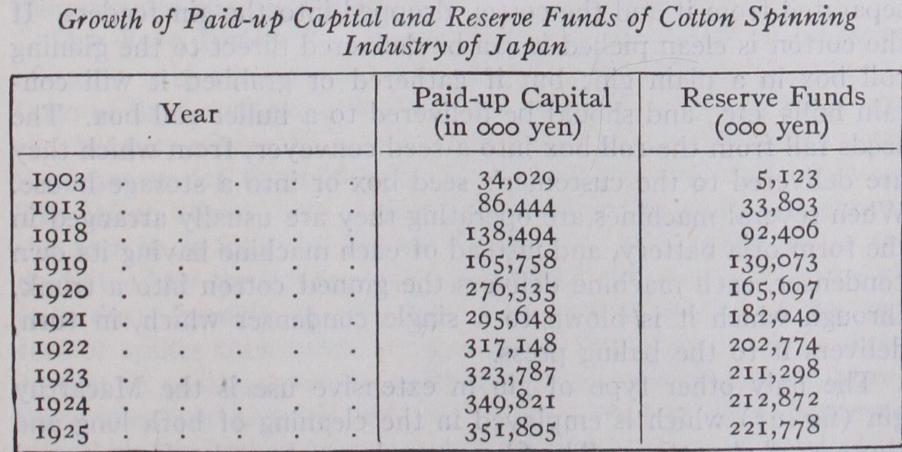

The World War naturally gave Japan an opportunity to gain a foothold in many markets— such as India, Dutch East Indies and South America—from which she had been kept before 1913 by the competition of the more firmly established cotton industries. The stimulating effect of the war had disappeared by 1927, but it left the cotton industry es tablished at a level well above that of 1913. The industry was, therefore, in a very strong position. In 1927 it had nearly three times as many looms and twice as many spindles as in 1913, and it was rapidly producing a body of industrial workers whose skill would enable the output of much finer cloths than had been pro duced in the past, and it controlled in large measure the growing textile industry of China. The extremely strong capital position 9f the industry was the result of the far-sighted policy adopted by the mill owners in building up, out of the large profits being made during the war, capital reserves which were strong enough to carry the mills over the difficulties of the years of ter the war, and which were available to meet immediately the heavy losses caused by the earthquake of 1923. This is clearly shown below.

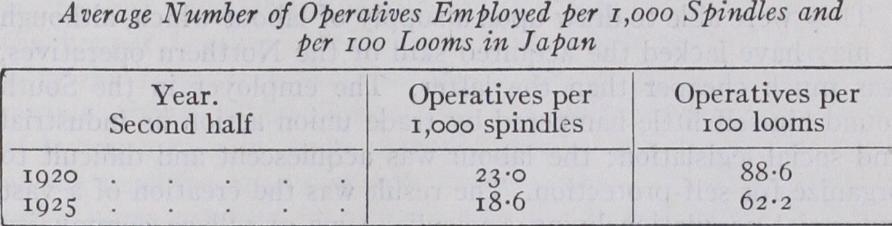

The tendency which has been noticed for the cotton industry in India to expand in new areas finds its counterpart in Japan, where the former concentration of spindles in Osaka began to break down after the war with the growth in outside districts. At the end of 1925, 24% of the total spindleage was to be found in the prefecture of Osaka, but the price of land there had become so high with the concentration of industry and population that this percentage tended to decrease as the cotton mills in Aichi, and particularly Nagoya, developed. The war-boom prosperity was not allowed to wane from any lack of technical efficiency. Elec tricity has largely replaced steam as the motive power and the bulk of the mills now use electricity with a consequent reduction in the cost of production. Either as the outcome of the increased efficiency of the operatives or the use of machinery more easily controlled, or both, the number of operatives employed per active spindle or loom decreased in the manner shown by figures taken from W. B. Cunningham's report on the Cotton Spinning and Weaving Industry of Japan.

The result of this technical improvement was the movement of the industry towards finer production shown both by the higher range of counts which are now being spun and the increased con sumption of American cotton.

The United States Cotton Industry.

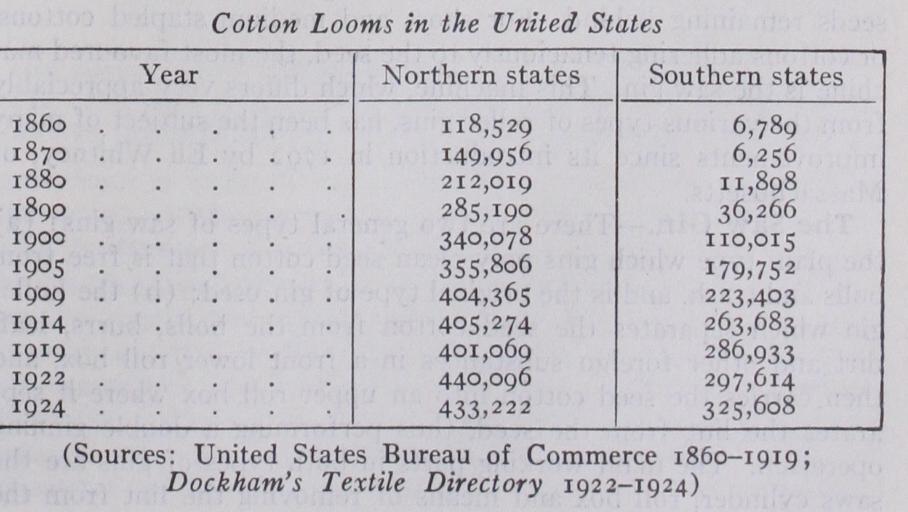

The cotton industry of the United States experienced neither the abnormal stimulus of war felt by the Eastern countries nor the drastic check imposed upon the Lancashire industry by the post-war conditions. Its his tory since 1913 has, therefore, been less eventful than the turbu lence of decline or growth in many other countries. But if, to the outside world, the industry presents an aspect of stability and nor mality, from within it shows sign of rapid and significant re transference and redistribution.The industry has for long been concentrated in two areas. The New England States were the original home of cotton manufac ture, but towards the end of the 19th century spindles and looms began to be established in the Southern States and particularly in the cotton-growing States. Up to 1913 both sections showed rapid growth based upon the steadily increasing demands of the home market. After the conclusion of the World War that position changed. The New England textile industry felt a depression as long continued and almost as keen as that in England. The in dustry of the Southern States gathered strength and impetus until it rivalled its competitor in output and in capital equipment. The speed with which the new overhauled the old industry is shown by the figures of looms established. The figures for 1922 and 1924 taken from Dockham's Textile Directory are not strictly comparable with the earlier statistics taken from United States Bureau of Commerce, since the former includes certain types of manufacture not included by the latter, so that the increase shown in 1922 and 1924 is largely fictitious. The comparison of North ern with Southern States is still, however, useful and significant.

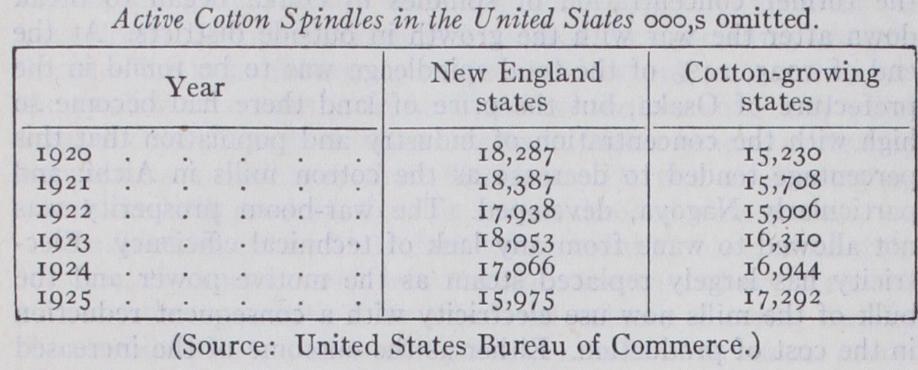

On the spinning side the cotton-growing States actually sup planted the New England States.

The industry, in the years after the war, was readjusting itself to the new relation of productive costs in the two areas. The Southern States had the advantage of working near to the supplies of raw material and thus eliminating heavy railway freights.

They were able to draw upon a supply of labour which, although it may have lacked the acquired skill of the Northern operatives, was much cheaper than the latter. The employer in the South found himself little hampered by trade union action or industrial and social legislation; the labour was acquiescent and difficult to organize for self-protection. The result was the creation of a vast industrial population living a peculiar type of village community life, reserved, intolerant, bearing upon it the industrial irregularity and inconsistency of a people who still show signs of their pre viously, isolated, agricultural existence.

movement of agricultural and industrial prices since 1913 is given in Memorandum on Balances of Payments and Foreign Trade Balances, 1911-25, vol. i., issued by the League of Nations, 1926. The Report of the Indian Tariff Board, 1927, gives a detailed account of the Indian industry since 1913. The conditions in Japan are outlined in W. B. Cunningham, Report on the Cotton Spinning and Weaving Industry in Japan, 1925-26. For the recent changes in the United States, Holland Thompson, Cotton Mill People of the Piedmont; M. A. Polwin, The New South; B. Mitchell, The Rise of the Cotton Mills in the South, and F. Tannenbaum, Darker Phases of the South, should be consulted. (J. JE.)