Physical Properties of Crystals

PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF CRYSTALS Many of the physical properties of crystals vary with the direction in the material, but are the same in certain directions; these directions obeying the same laws of symmetry as do the faces on the exterior of the crystal. The symmetry of the internal structure of crystals is thus the same as the symmetry of their external form.

(a) Elasticity and Cohesion The elastic constants of crystals are determined by similar methods to those employed with amorphous substances, only the bars and plates experimented upon must be cut from the crystal with known orientations. The "elasticity surface" express ing the coefficients in various directions within the crystal has a configuration symmetrical with respect to the same planes and axes of symmetry as the crystal itself. In calcite, for instance, the figure has roughly the shape of a rounded rhombohedron with depressed faces and is symmetrical about three vertical planes. In the case of homogeneous elastic deformation, produced by pressure on all sides, the effect on the crystal is the same as that due to changes of temperature; and the surfaces expressing the compression coefficients in different directions have the same higher degree of symmetry, being either a sphere, spheroid or ellipsoid. When-strained beyond the limits of elasticity, crystalline matter may suffer permanent deformation in one or other of two ways, or may be broken along cleavage surfaces or with an irregu lar fracture. In the case of plastic deformation, e.g., in a crystal of ice, the crystalline particles are displaced but without any change in their orientation. Crystals of some substances (e.g., para-azoxyanisol) have such a high degree of plasticity that they are deformed even by their surface tension, and the crystals take the form of drops of doubly refracting liquid which are known as "liquid crystals." (See O. Lehmann, Fliissige Kristalle, Leipzig, 1921.) In the second, and more usual kind of permanent deformation without fracture, the particles glide along certain planes into a new (twinned) position of equilibrium. If a knife-blade be pressed into the edge of a cleavage rhombohedron of calcite (at b, fig. 91) the portion abcde of the crystal will take up the position a'b'cde. The obtuse solid angle at abecomes acute (a'), whilst the acute angle at b be comes obtuse (b') ; and the new surface a'ce is as bright and smooth as before. This result has been effected by the particles in successive layers gliding or rotating over each other, without separation, along panes parallel to cde. This plane, which truncates the edge of the rhombohedron and has the indices { I I O } is called a "glide-plane." The new portion is in twinned position with respect to the rest of the crystal, being a reflection of it across the plane cde, which is therefore a plane of twinning. This secondary twinning is often to be observed as a repeated lamination in the grains of calcite composing a crystal line limestone, or marble, which has been subjected to earth movements. Planes of gliding have been observed in many minerals (pyroxene, corundum, etc.) and their crystals may often be readily broken along these directions, which are thus "planes of parting" or "pseudo-cleavage." The characteristic transverse striae, invariably present on the cleavage surfaces of stibnite and kyanite are due to secondary twinning along glide-planes, and have resulted from the bending of the crystals.

One of the most important characters of crystals is that of "cleavage"; there being certain plane directions across which the cohesion is a minimum, and along which the crystal may be readily split or cleaved. These directions are always parallel to a possible face on the crystal and usually one prominently devel oped and with simple indices, it being a face in which the crystal molecules are most closely packed. The directions of cleavage are symmetrically repeated according to the degree of symmetry possessed by the crystal. Thus in the cubic system, crystals of salt and galena cleave in three directions parallel to the faces of the cube { I00 } , diamond and fluorspar cleave in four direc tions parallel to the octahedral faces {III }, and blende in six directions parallel to the faces of the rhombic dodecahedron { II o} . In crystals of other systems there will be only a single direction of cleavage if this is parallel to the faces of a pinacoid; e.g., the basal pinacoid in tetragonal (as in apophyllite) and hexa gonal crystals; or parallel (as in gypsum) or perpendicular (as in mica and cane-sugar) to the plane of symmetry in monoclinic crystals. Calcite cleaves in three directions parallel to the faces of the primitive rhombohedron. Barytes, which crystallizes in the orthorhombic system, has two sets of cleavages, viz., a single cleavage parallel to the basal pinacoid { oor} and also two di rections parallel to the faces of the prism { I Io } . In all of the examples just quoted the cleavage is described as perfect, since cleavage flakes with very smooth and bright surfaces may be readily detached from the crystals. Different substances, however, vary widely in their character of cleavage; in some it can only be described as good or distinct, whilst in others, e.g., quartz and alum, there is little or no tendency to split along certain direc tions and the surfaces of fracture are very uneven. Cleavage is therefore a character of considerable determinative value, espe cially for the purpose of distinguishing different minerals.

Another result of the presence in crystals of directions of mini mum cohesion are the "percussion figures," which are produced on a crystal-face when this is struck with a sharp point. A percussion figure consists of linear cracks radiating from the point of impact, which in their number and orientation agree with the symmetry of the face. Thus on a cube face of a crystal of salt the rays of the percussion. figure are parallel to the diagonals of the face, whilst on an octahedral face a three-rayed star is developed. By pressing a blunt point into a crystal face a somewhat similar figure, known as a "pressure figure," is pro duced. Percussion and pressure figures are readily developed in cleavage sheets of mica (q.v.).

Closely allied to cohesion is the character of "hardness," which is often defined, and measured by, the resistance which a crystal face offers to scratching. That hardness is a character depending largely on crystalline structure is well illustrated by the two crystalline modifications of carbon : graphite is one of the softest of minerals, whilst diamond is the hardest of all. The hardness of crystals of different substances thus varies widely, and with minerals it is a character of considerable determinative value; for this purpose a scale of hardness is employed. (See MIN ERALOGY.) Various attempts have been made with the view of obtaining accurate determinations of degrees of hardness, but with varying results; an instrument used for this purpose is called a sclerometer (from crrcX npos, hard) . It may, however, be readily demonstrated that the degree of hardness on a crystal face varies with the direction, and that a curve expressing these relations possesses the same geometrical symmetry as the face itself. The mineral kyanite is remarkable in having widely different degrees of hardness on different faces of its crystals and in differ ent directions on the same face.

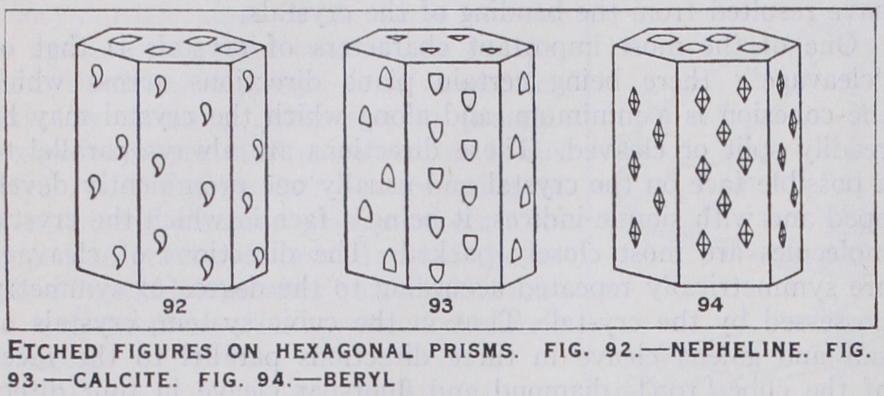

Another result of the differences of cohesion in different direc tions is that crystals are corroded, or acted upon by chemical solvents, at different rates in different directions. This is strikingly shown when a sphere cut from a crystal, say of calcite or quartz, is immersed in acid; after some time the resulting form is bounded by surfaces approximating to crystal faces, and has the same symmetry as that of the crystal from which the sphere was cut. When a crystal bounded by faces is immersed in a solvent the edges and corners become rounded and "prerosion faces" developed in their place; the faces become marked all over with minute pits or shallow depressions, and as these are extended by further solution they give place to small elevations on the corroded face. The sides of the pits and elevations are hounded by small faces which have the character of vicinal faces. These markings are known as "etched figures" or "corrosion fig ures," and they are extremely important aids in determining the symmetry of crystals. Etched figures are sometimes beautifully developed on the faces of natural crystals, e.g., of diamond, and they may be readily produced artificially with suitable solvents.

As an example, the etched figures on the faces of a hexagonal prism and the basal plane are illustrated in figs. 92-94 for three of the several symmetry-classes of the hexagonal system. The classes chosen are those in which nepheline, calcite and beryl (emerald) crystallize, and these minerals often have the simple form of crystal represented in the figures. In nepheline (fig. 92) the only element of symmetry is a hexad axis; the etched fig ures on the prism are therefore unsymmetrical, though similar on all the faces; the hexagonal markings on the basal plane have none of their edges parallel to the edges of the face; further the crystals being hemimorphic, the etched figures on the basal planes at the two ends will be different in character. The facial development of crystals of nepheline gives no indication of this type of symmetry, and the mineral has been referred to this class solely on the evidence afforded by the etched figures. In calcite there is a triad axis of symmetry parallel to the prism edges, three dyad axes each perpendicular to a pair of prism edges and three planes of symmetry perpendicular to the prism faces; the etched figures shown in fig. 93 will be seen to conform to all these elements of symmetry. There being in calcite also a centre of symmetry, the equilateral triangles on the basal plane at the lower end of the crystal will be the same in form as those at the top, but they will occupy a reversed position. In beryl, which crystallizes in the holosymmetric class of the hexagonal system, the etched figures (fig. 94) display the fullest possible degree of symmetry ; those on the prism faces are all similar and are each symmetrical with respect to two lines, and the hexagonal mark ings on the basal planes at both ends of the crystal are sym metrically placed with respect to six lines. A detailed account of the etched figures of crystals is given by H. Baumhauer, Die Resultate der Atzmethode in der krystallographischen Forschung (Leipzig, 1894).

(b) Optical Properties The complex optical characters of crystals are not only of considerable interest theoretically, but are of the greatest practical importance. In the absence of external crystalline form, as with a faceted gem-stone, or with the minerals constituting a rock (thin, transparent sections of which are examined in the polarizing microscope), the mineral species may often be readily identified by the determination of some of the optical characters.

According to their action on transmitted plane-polarized light (see POLARIZATION OF LIGHT) all crystals may be referred to one or other of the five groups enumerated below. These groups correspond with the six systems of crystallization (in the second group two systems being included together). The several sym metry-classes of each system are optically the same, except in the rare cases of substances which are circularly polarizing.

(I ) Optically isotropic crystals—corresponding with the cubic system.

(2) Optically uniaxial crystals—corresponding with the tetragonal and hexagonal systems.

(3) Optically biaxial crystals in which the three principal optical directions coincide with the three crystallographic axes— corresponding with the orthorhombic system.

(4) Optically biaxial crystals in which only one of the three principal optical directions coincides with a crystallographic axis —corresponding with the monoclinic system.

(5) Optically biaxial crystals in which there is no fixed and definite relation between the optical and crystallographic direc tions—corresponding with the anorthic system.

Optically Isotropic Crystals.

These belong to the cubic sys tem, and like all other optically isotropic (from 'loos, like, and Tpolros, character) bodies have only one index of refraction for light of each colour. They have no action on polarized light (except in crystals which are circularly polarizing) ; and when examined in the polariscope or polarizing microscope they remain dark between crossed nicols, and cannot therefore be distinguished optically from amorphous substances, such as glass and opal.

Optically Uniaxial Crystals.

These belong to the tetragonal and hexagonal (including rhombohedral) systems, and between crystals of these systems there is no optical distinction. Such crystals are anisotropic or doubly refracting (see REFRACTION : Double) ; but for light travelling through them in a certain, single direction they are singly refracting. This direction, which is called the optic axis, is the same for light of all colours and at all temperatures; it coincides in direction with the principal crystallographic axis, which in tetragonal crystals is a tetrad (or dyad) axis of symmetry, and in the hexagonal system a triad or hexad axis.For light of each colour there are two indices of refraction ; namely, the ordinary index (w) corresponding with the ordinary ray, which vibrates perpendicular to the optic axis; and the extraordinary index (E) corresponding with the extraordinary ray. which vibrates parallel to the optic axis. If the ordinary index of refraction be greater than the extraordinary index, the crystal is said to be optically negative, whilst if less the crystal is optically positive. The difference between the two indices is a measure of the strength of the double refraction or birefringence. Thus in calcite, for sodium (D) light, w= and E = 1.4863 ; hence this substance is optically negative with a relatively high double refraction of co—E= 0.1722. In quartz E and e—w =0.0091; this mineral is there fore optically positive with low double refraction. The indices of refraction vary, not only for light of different colours, but also slightly with the temperature.

The optical characters of uniaxial crystals are symmetrical not only with respect to the full number of planes and axes of symmetry of tetragonal and hexagonal crystals, but also with respect to all vertical planes, i.e., all planes containing the optic axis. A surface expressing the optical relations of such crystals is thus an ellipsoid of revolution about the optic axis. (In cubic crystals the corresponding surface is a sphere.) In the "optical indicatrix" (L. Fletcher, The Optical Indicatrix and the Trans mission of Light in Crystals, London, 1892), the length of the principal axis, or axis of rotation, is proportional to the index of refraction (i.e., inversely proportional to the velocity) of the extraordinary rays, which vibrate along this axis and are trans mitted in directions perpendicular thereto ; the equatorial diameters are proportional to the index of refraction of the ordi nary rays, which vibrate perpendicular to the optic axis. For positive uniaxial crystals the indicatrix is thus a prolate spheroid (egg-shaped), and for negative crystals an oblate spheroid (orange-shaped) .

In "Fresnel's ellipsoid" the axis of rotation is proportional to the velocity of the extraordinary ray, and the equatorial diam eters proportional to the velocity of the ordinary ray ; it is therefore an oblate spheroid for positive crystals, and a prolate spheroid for negative crystals. The "ray-surface," or "wave surface," which represents the distances traversed by the rays during a given interval of time in various directions from a point of origin within the crystal, consists in uniaxial crystals of two sheets; namely, a sphere, corresponding to the ordinary rays, and an ellipsoid of revolution, corresponding to the extra ordinary rays. The difference in form of the ray-surface for positive and negative crystals is shown in figs. 95 and 96.

When a uniaxial crystal is examined in a polariscope or polarizing microscope be tween crossed nicols (i.e.,with the principal planes of the polarizer or analyser at right angles, and so producing a dark field of view) its behaviour differs according to the direction in which the light travels through the crystal, to the position of the crystal with respect to the principal planes of the nicols, and further, whether convergent or parallel polarized light be employed. A tetragonal or hexagonal crystal viewed, in parallel light, through the basal plane, i.e., along the principal axis, will remain dark as it is rotated between crossed nicols, and will thus not differ in its behaviour from a cubic crystal or other isotropic body. If, however, the crystal be viewed in any other direction, for example, through a prism face, it will, except in certain positions, have an action on the polarized light. A plane polarized ray entering the crystal will be resolved into two polarized rays with the directions of vibration parallel to the vibration-ciirections in the crystal. These two rays on leaving the crystal will be combined again in the analyser, and a portion of the light transmitted through the instrument ; the crystal will then show up brightly against the dark field. Further, owing to interference of these two rays in the analyser, the light will be brilliantly coloured, especially if the crystal be thin, or if a thin section of a crystal be examined. The particular colour seen will depend on the strength of the double refraction; the orientation of the crystal or section, and upon its thickness. If now, the crystal be rotated with the stage of the microscope, the nicols remaining fixed in position, the light transmitted through the instrument will vary in intensity, and in certain positions will be cut out altogether. The latter happens when the vibration-directions of the crystal are parallel to the vibration directions of the nicols (these being indicated by cross-wires in the microscope). The crystal, now being dark, is said to be in position of extinction ; and as it is turned through a complete rotation of 36o° it will extinguish four times. If a prism face be viewed through, it will be seen that, when the crystal is in a position of ex tinction, the cross-wires of the micro scope are parallel to the edges of the prism : the crystal is then said to give "straight extinction." In convergent light, between crossed nicols, a very different phenomenon is to be observed when a uniaxial crystal, or ' tion of such a crystal, is placed with its tic axis coincidentwiththeaxisof the scope. The rays of light, being convergent, do not travel in the direction of the optic axis and are therefore doubly refracted in the crystal; in the analyser the vibrations will be reduced to the same plane and there will be interference of the two sets of rays. The result is an "interference figure" (fig. 97), which consists of a number of brilliantly coloured centric rings, each showing the colours of the spectrum of white light ; intersecting the rings is a black cross, the arms of which are parallel to the principal planes of the nicols. If monochro matic light be used instead of white light, the rings will be alter nately light and dark. The number and distance apart of the rings depend on the strength of the double refraction and on the thickness of the crystal. By observing the effect produced on such a uniaxial interference figure when a "quarter undulation (or wave-length) mica-plate" is superposed on the crystal, it may be at once decided whether the crystal is optically positive or negative. Such a simple test may, for example, be applied for distinguishing certain faceted gem-stones : thus zircon and phenakite are optically positive, whilst corundum (ruby and sapphire) and beryl (emerald) are optically negative.

Optically Biaxial Crystals.—In these crystals there are three principal indices of refraction, denoted by a, (3 and y ; of these y is the greatest and a the least (y > (3 > a) . The three principal vibration-directions, corresponding to these indices, are at right angles to each other, and are the directions of the three rect angular axes of the optical indicatrix. The indicatrix (fig. 98) is an ellipsoid with the lengths of its axes proportional to the refractive indices ; OC = y, OB = (3, OA = a, where OC > OB > OA. The figure is symmetrical with respect to the principal planes OAB, OAC, OBC.

In Fresnel's ellipsoid the three rectangular axes are proportional to 1/33, and 1/ y, and are usually denoted by a, b and respectively, where a>b>c : these have often been called "axes of optical elasticity," a term now generally discarded.

The ray-surface (represented in fig. 99 by its sections in the three principal planes) is derived from the indicatrix in the following manner. A ray of light entering the crystal and travel ling in the direction OA is resolved into polarized rays vibrating parallel to OB and OC, and therefore propagated with the veloci ties 1A3 and i/y respectively : distances Ob and Oc (fig. 99) proportional to these velocities are marked off in the direction OA. Similarly, rays travelling along OC have the velocities and i/0, and those along OB the velocities 1/ca and O. In the two directions Opp and Opt (fig. 98), per pendicular to the two circular sections and of the indicatrix, the two rays will be transmitted with the same velocity These two directions are called the optic axes ("primary optic axis"), though they have not all the properties which are associated with the optic axis of a uniaxial crystal. They have very nearly the same direction as the lines and in fig. 99, which are distinguished as the "secondary optic axes." In most crystals the primary and secondary optic axes are inclined to each other at not more than a few minutes, so that for practical purposes there is no distinction between them.

The angle between

Opp and Opt is called the "optic axial angle" ; and the plane OAC in which they lie is called the "optic axial plane." The angles between the optic axes are bisected by the vibration-directions OA and OC; the one which bisects the acute angle being called the "acute bisectrix" or "first mean line," and the other the "obtuse bisectrix" or "second mean line." When the acute bisectrix coincides with the greatest axis OC of the indicatrix, i.e.,the direction corresponding with the refractive index y (as in figs. 98 and 99), the crystal is described as being optically positive ; and when the acute sectrix coincides with OA, the vibration-direction for the index a the crystal is negative. The distinction between positive and tive biaxial crystals thus depends on the relative magnitude of the three principal indices of refraction ; in positive crystals 03 is nearer to a than to y whilst in negative crystals the reverse is the case. Thus in topaz, which is optically positive, the refractive indices for sodium light are a = 1.612o, (3 = 1.615o, y= 1.6224; and for orthoclase which is optically negative, a = i. igo, = 'Y =I•5260. The difference 7— a represents the strength of the double refraction.

Since the refractive indices vary both with the colour of the light and with the temperature, there will be for each colour and temperature slight differences in the form of both the indicatrix and the ray-surface; consequently there will be variations in the positions of the optic axes and in the size of the optic axial angle. This phenomenon is known as the "dispersion of the optic axes." When the axial angle is greater for red light than for blue the character of the dispersion is expressed by p> v, and when less by p

In some crystals, e.g., brookite, the optic axes for red light and for blue light may be, at certain temperatures, in planes at right angles.

The type of interference figure exhibited by a biaxial crystal in convergent polarized light between crossed nicols is represented in figs. i oo and i o i . The crystal must be viewed along the acute bisectrix, and for this purpose it is of ten necessary to cut a plate from the crystal perpendicular to this direction : sometimes, however, as in mica and topaz, a cleavage flake will be perpen dicular to the acute bisectrix. When seen in white light, there are around each optic axis a series of bril liantly coloured ovals, which at the centre join to form an 8-shaped loop, whilst farther from the centre the curvature of the rings is approximately that of lemniscates. In the position shown in fig. ioo the vibration-directions in the crystal are parallel to those of the nicols, and the figure is intersected by two black bands or "brushes" forming a cross. When, however, the crystal is rotated with the stage of the microscope the cross breaks up into the two branches of a hyperbola, and when the vibration directions of the crystal are inclined at 45° to those of the nicols the figure is that shown in fig. ioi. The points of emergence of the optic axes are at the middle of the hyperbolic brushes when the crystal is in the diagonal position : the size of the optic axial angle can therefore be directly measured with considerable accuracy.

In orthorhombic crystals the three principal vibration-direc tions coincide with the three crystallographic axes, and have therefore fixed positions in the crystal, which are the same for light of all colours and at all temperatures. The optical orienta tion of an orthorhombic crystal is completely defined by stating to which crystallographic planes the optic axial plane and the acute bisectrix are respectively parallel and perpendicular. Ex amined in parallel light between crossed nicols, such a crystal extinguishes parallel to the crystallographic axes, which are often parallel to the edges of a face or section ; there is thus usually "straight extinction." The interference figure seen in convergent polarized light is symmetrical about two lines at right angles.

In monoclinic crystals only one vibration-direction has a fixed

position within the crystal, being parallel to the ortho-axis (i.e.,

perpendicular to the plane of symmetry or the plane { oio} ).

The other two vibration-directions

lie in the plane { oio } , but they

may vary in position for light of

different colours and at different

temperatures. In addition to

persion of the optic axes there

may thus, in crystals of this

tem, be also "dispersion of the

bisectrices." The latter may be of one or other of three kinds,

according to which of the three vibration-directions coincides

with the ortho-axis of the crystal. When the acute bisectrix

is fixed in position, the optic axial planes for different colours

may be crossed, and the interference figure will then be

metrical with respect to a point only ("crossed dispersion").

When the obtuse bisectrix is fixed, the axial planes may be

clined to one another, and the interference figure is symmetrical only about a line which is perpendicular to the axial planes ("horizontal dispersion"). Finally, when the vibration-direction corresponding to the refractive index (3, or the "third mean line," has a fixed position, the optic axial plane lies in the plane { ow o } , but the acute bisectrix may vary in position in this plane; the interference figure will then be symmetrical only about a line joining the optic axes ("inclined dispersion"). Examples of substances exhibiting these three kinds of dispersion are borax, orthoclase and gypsum respectively. In orthoclase and gypsum, however, the optic axial angle gradually diminishes as the crys tals are heated, and after passing through a uniaxial position they open out in a plane at right angles to the one they previously occupied ; the character of the dispersion thus becomes reversed in the two examples quoted. When examined in parallel light between crossed nicols monoclinic crystals will give straight extinction only in faces and sections which are perpendicular to the plane of symmetry (or the plane { oio}) ; in all other faces and sections the extinction-directions will be inclined to the edges of the crystal. The angles between these directions and edges are readily measured, and, being dependent on the optical orientation of the crystal, they are often characteristic constants of the sub stance. (See, e.g., PLAGIOCLASE.) In anorthic crystals there is no relation between the optical and crystallographic directions, and the exact determination of the optical orientation is often a matter of considerable difficulty. The character of the dispersion, of the bisectrices and optic axes is still more complex than in monoclinic crystals, and the inter ference figures are devoid of symmetry.

Absorption of Light in Crystals: Pleochroism.—In

tals other than those of the cubic system, rays of light with

ent vibration-directions will, as a rule, be differently absorbed; and

the polarized rays on emerging from the crystal may be of

ent intensities and (if the observation be made in white light and

the crystal is coloured) differently coloured. Thus, in tourmaline

the ordinary ray, which vibrates perpendicular to the principal

axis, is almost completely absorbed, whilst the extraordinary ray

is allowed to pass through the crystal. A plate of tourmaline cut

parallel to the principal axis may therefore be used for producing

a beam of polarized light, and two such plates placed in crossed

position form the polarizer or analyser of "tourmaline tongs,"

with the aid of which the interference figures of crystals may be

simply shown. Uniaxial (tetragonal and hexagonal) crystals when

showing perceptible differences in colour

for the ordinary and extraordinary rays are

said to be "dichroic." In biaxial

rhombic, monoclinic and anorthic) crystals,

rays vibrating along each of the three

cipal vibration-directions maybe differently

absorbed, and, in coloured crystals,

ently coloured; such crystals are therefore

said to be "trichroic" or in general

ochroic" (from 7rXfwv, more, and xpcis,

colour). The directions of maximum

sorption in biaxial crystals have, however,

no necessary relation with the axes of the

indicatrix, unless these have fixed

graphic directions, as in the orthorhombic

system and the ortho-axis in the

clinic. In epidote it has been shown that

the two directions of maximum absorption

which lie in the plane of symmetry are not even at right angles.

The pleochroism of some crystals is so strong that when they

are viewed through in different directions they exhibit marked

differences in colour. Thus a crystal of the mineral cordierite

(called also dichroite because of its strong pleochroism) will be

seen to be dark blue, pale blue or pale yellow according to which

of three perpendicular directions it is viewed. The "face colours"

seen directly in this way result, however, from the mixture of two

"axial colours" belonging to rays vibrating in two directions.

In order to see the axial colours separately the crystal must be

examined with a dichroscope, or in a polarizing microscope from

which the analyser has been removed. The dichroscope, or dichro iscope (fig. 1o2), consists of a cleavage rhombohedron of calcite (Iceland-spar) p, on the ends of which glass prisms w are ce mented : the lens 1 is focused on a small square aperture o in the tube of the instrument. The eye of the observer placed at e will see two images of the square aperture, and if a pleochroic crystal be placed in front of this aperture the two images will be dif ferently coloured. On rotating this crystal with respect to the instrument the maximum difference in the colours will be obtained when the vibration-directions in the crystal coincide with those in the calcite. Such a simple instrument is especially useful for the examination of faceted gemstones, even when they are mounted in their settings. A single glance suffices to distinguish between a ruby and a "spinel-ruby," since the former is dichroic and the latter isotropic and therefore not dichroic.

The characteristic absorption bands in the spectrum of white light which has been transmitted through certain crystals, par ticularly those of salts of the cerium metals, will, of course, be different according to the direction of vibration of the rays.

Circular Polarization in Crystals.—Like the solutions of certain optically active organic substances, such as sugar and tar taric acid, some optically isotropic and uniaxial crystals possess the property of rotating the plane of polarization of a beam of light. This property has also been proved, but much less easily, in certain biaxial crystals. In uniaxial (tetragonal and hexagonal) crystals it is only for light transmitted in the direction of the optic axis that there is rotatory action, but in isotropic (cubic) crystals all directions are the same in this respect. Examples of circularly polarizing cubic crystals are sodium chlorate, sodium bromate, and sodium uranyl acetate; amongst tetragonal crystals are strychnine sulphate and guanidine carbonate; amongst rhom bohedral are quartz (q.v.) and cinnabar (q.v.) (these being the only two mineral substances in which the phenomenon has been observed), dithionates of potassium, lead, calcium and strontium, and sodium periodate; and amongst hexagonal crystals is potas sium lithium sulphate. Crystals of all these substances belong to one or other of the several symmetry-classes in which there are neither planes nor centre of symmetry, but only axes of sym metry. They crystallize in two complementary hemihedral forms, which are respectively right-handed and left-handed, i.e., enan tiomorphous forms. Some other substances which crystallize in enantiomorphous forms are, however, only "optically active" when in solution (e.g., sugar and tartaric acid) ; and there are many other substances presenting this peculiarity of crystalline form which are not circularly polarizing either when crystallized or when in solution. Further, in the examples quoted above, the rotatory power is lost when the crystals are dissolved (except in the case of strychnine sulphate, which is only feebly active in solution). The rotatory power is thus due to different causes in the two cases, in the one depending on a spiral arrangement of the crystal particles, and in the other on the structure of the molecules themselves.

The circular polarization of crystals may be imitated by a pile of mica plates, each plate being turned through a small angle on the one below, thus giving a spiral arrangement to the pile.

"Optical Anomalies" of Crystals.

When, in 1818, Sir David Brewster established the important relations existing between the optical properties of crystals and their external form, he at the same time noticed many apparent exceptions. For example, he observed that crystals of leucite and boracite, which are cubic in external form, are always doubly refracting and optically bi axial, but with a complex internal structure; and that cubic crys tals of garnet and analcime sometimes exhibit the same phenom ena. Also some tetragonal and hexagonal crystals, e.g., apo phyllite, idocrase, beryl, etc., which should normally be optically uniaxial, sometimes consist of several biaxial portions arranged in sectors or in a quite irregular manner. Such exceptions to the general rule have given rise to much discussion. They have often been considered to be due to internal strains in the crystals, set up as a result of cooling or by earth pressures, since similar phe nomena are observed in chilled and compressed glasses and in dried gelatine. In many cases, however, as shown by E. Mallard, in 1876, the higher degree of symmetry exhibited by the external form of the crystals is the result of mimetic twinning, as in the pseudo-cubic crystals of leucite (q.v.) and boracite (q.v.). In other instances substances not usually regarded as cubic, e.g., the monoclinic phillipsite (q.v.), may by repeated twinning give rise to pseudo-cubic forms. In some cases it is probable that the sub stance originally crystallized in one modification at a higher tem perature, and when the temperature fell it became transformed into a dimorphous modification, though still preserving the external form of the original crystal. (See BORACITE.) A summary of the literature is given by R. Brauns, Die optischen Anomalien der Krystalle (Leipzig, 1891).

The thermal properties of crystals present certain points in common with the optical properties. Heat rays are transmitted and doubly refracted like light rays ; and surfaces expressing the conductivity and dilatation in different directions possess the same degree of symmetry and are related in the same way to the crystallographic axes as the ellipsoids expressing the optical relations. That crystals conduct heat at different rates in dif ferent directions is well illustrated by the following experiment. Two plates (fig. 103) cut from a crystal of quartz, one parallel to the principal axis and the other perpendicular to it, are coated with a thin layer of wax, and a hot wire is applied to a point on the surface. On the transverse section the wax will be melted in a circle, and on the longitudinal section (or on the natural prism faces) in an ellipse. The isothermal surface in a uniaxial crystal is therefore a spheroid; in cubic crystals it is a sphere; and in biaxial crystals an ellipsoid, the three axes of which coincide, in orthorhombic crystals, with the crystallographic axes.

With change of temperature cubic crystals expand equally in all directions, and the angles between the faces are the same at all temperatures. In uniaxial crystals there are two principal coeffi cients of expansion; the one measured in the direction of the principal axis may be either greater or less than that measured in directions perpendicular to this axis. A sphere cut from a uni axial crystal at one temperature will be a spheroid at another temperature. In biaxial crysta'_s there are different coefficients of expansion along three rectangular axes, and a sphere at one temperature will be an ellipsoid at another. A result of this is that for all crystals, except those belonging to the cubic system, the angles between the faces will vary, though only slightly, with changes of temperature. E. Mitscherlich found that the rhombo hedral angle of calcite decreases 8' 37" as the crystal is raised in temperature from o° to ioo° C.

As already mentioned, the optical properties of crystals vary considerably with the temperature. Such characters as specific heat and melting-point do not vary with the direction.

(D) MAGNETIC AND ELECTRICAL PROPERTIES Crystals, like other bodies, are either paramagnetic or dia magnetic, i.e., they are either attracted or repelled by the pole of a magnet. In crystals other than those belonging to the cubic system, however, the relative strength of the induced magnetiza tion is different in different directions within the mass. A sphere cut from a tetragonal or hexagonal (uniaxial) crystal will if freely suspended in a magnetic field (between the poles of a strong electromagnet) take up a position such that the principal axis of the crystal is either parallel or perpendicular to the lines of force, or to a line joining the two poles of the magnet. Which of these two directions is taken by the axis depends on whether the crystal is paramagnetic or diamagnetic, and on whether the principal axis is the direction of maximum or minimum magnet ization. The surface expressing the magnetic character in different directions is in uniaxial crystals a spheroid; in cubic crystals it is a sphere. In orthorhombic, monoclinic and anorthic crystals there are three principal axes of magnetic induction, and the surface is an ellipsoid, which is related to the symmetry of the crystal in the same way as the ellipsoids expressing the thermal and optical properties.

Similarly, the dielectric constants of a non-conducting crystal may be expressed by a sphere, spheroid or ellipsoid. A sphere cut from a crystal will when suspended in an electromagnetic field set itself so that the axis of maximum induction is parallel to the lines of force.

The electrical conductivity of crystals also varies with the direction, and bears the same relation to the symmetry as the thermal conductivity. In a rhombohedral crystal of haematite the electrical conductivity along the principal axis is only half as great as in directions perpendicular to this axis ; whilst in a crystal of bismuth, which is also rhombohedral, the conductivities along and perpendicular to the axis are as i .6 :1.

Conducting crystals are thermo-electric : when placed against another conducting substance and the contact heated there will be a flow of electricity from one body to the other if the circuit be closed. The thermo-electric force depends not only on the nature of the substance, but also on the direction within the crystal, and may in general be expressed by an ellipsoid. A remarkable case is,' however, presented by minerals of the pyrites group : some crystals of pyrites are more strongly thermo electrically positive than antimony, and others more negative than bismuth, so that the two when placed together give a stronger thermo-electric couple than do antimony and bismuth. In the thermo-electrically positive crystals of pyrites the faces of the pentagonal dodecahedron are striated parallel to the cubic edges, whilst in the rarer negative crystals the faces are striated per pendicular to these edges. Sometimes both sets of striae are present on the same face, and the corresponding areas are then thermo-electrically positive and negative.

The most interesting relation between the symmetry of crystals and their electrical properties is that presented by the pyro electrical phenomena of certain crystals. This is a phenomenon which may be readily observed, and one which often aids in the determination of the symmetry of crystals. It is exhibited by crystals in which there is no centre of symmetry, and the axes of symmetry are uniterminal or polar in character, being asso ciated with different faces on the crystal at their two ends. When a non-conducting crystal possessing this hemimorphic type of symmetry is subjected to changes of temperature a charge of positive electricity will be developed on the faces in the region of one end of the uniterminal axis, whilst the faces at the opposite end will be negatively charged. With rising temperature the pole which becomes positively charged is called the "analogous pole," and that negatively charged the "analogous pole" : with falling temperature the charges are reversed. The phenomenon was first observed in crystals of tourmaline, the principal axis of which is a uniterminal triad axis of symmetry. In crystals of quartz there are three uniterminal dyad axes of symmetry perpendicular to the principal triad axis (which is here similar at its two ends) : the dyad axes emerge at the edges of the hexag onal prism, alternate edges of which become positively and negatively charged on change of temperature. In boracite there are four uniterminal triad axes, and the faces of the two tetrahedra perpendicular to them will bear opposite charges. Other examples of pyro-electric crystals are the orthorhombic mineral hemi morphite (called also, for this reason, "electric calamine") and the monoclinic tartaric acid and cane-sugar, each of which pos sesses a uniterminal dyad axis of symmetry. In some exceptional cases, e.g., axinite, prehnite, etc., there is no apparent relation between the distribution of the pyro-electric charges and the symmetry of the crystals.

The distribution of the electric charges may be made visible by the following simple method, which may be applied even with minute crystals observed under the microscope. A finely powdered mixture of red-lead and sulphur is dusted through a sieve over the cooling crystal. In passing through the sieve the particles of red-lead and sulphur become electrified by mutual friction, the former positively and the latter negatively. The red-lead is therefore attracted to the negatively charged parts of the crystal and the sulphur to those positively charged, and the distribution of the charges over the whole crystal becomes mapped out in the two colours red and yellow.

Since, when a crystal changes in temperature, it also expands or contracts, a similar distribution of "piezo-electric" (from ire 'etv, to press) charges are developed when a crystal is sub jected to changes of pressure in the direction of a uniterminal axis of symmetry. Thus increasing pressure along the principal axis of a tourmaline crystal produces the same electric charges as decreasing temperature.

Crystals of various substances are extensively used as radio detectors in wireless telephony, but no satisfactory explanation of their action has yet been given. An essential character of crystals is a variation of many of their physical properties with the direction within the crystal—in other words, such properties are vectorial.