Special Curves

CURVES, SPECIAL. Partly due to the studies of the Greeks in pure geometry, but largely to the influence of analytic geometry (q.v.), there have been developed a large number of special curves which have received names which are more or less generally recognized. Such curves may be classified in various ways—curves in a plane or in a space of three dimensions; alge braic and non-algebraic ; alphabetically ; chronologically; etc. For reference purposes, however, it has seemed best to give an initial alphabetical list with references to the numbers of the sec tions, and then to arrange the sections roughly in the order: plane algebraic curves according to degree followed by plane transcen dental curves, general classes of curves, and curves of double curvature, inserting figures to show the general shapes of the most important plane curves considered.

I. Cubical Parabola (F. Parabole Cubique; G. Kubische Para bel), or one of the canonical forms of cubics studied by Newton and a particular case of the Pearls of Sluze. The name is usually applied to the special case y = (see fig.) which was first discussed by Leibniz (1675) who sought that curve for which the subnormal is always inverse ly proportional to the ordinate. It was used (a= i) by Monge (1815) to solve every equation of the form — px — q = o.

2. Semi-cubical Parabola or Neil's Para bola (F. Parabole Semi-cubique or Para bole de Neil; G. Semi-kubische Parabel), = aye, was the first algebraic curve recti fied (Neil, 1659) . It is the evolute of a parabola. Evolutes of parabolas and the lines of curvature of Enneper's minimal surface are the only cubics algebraically rectifiable (Raffy, L'Interm. d. Math., 1894, p. 1o6). In 1687 Leibniz proposed the problem to find the plane curve down which a particle may descend under the ac tion of gravity so as to describe equal vertical spaces in equal times, the initial velocity of the particle not being zero. Huygens found the curve at once to be a semi-cubical parabola, cuspidal tangent vertical, and thus it is called an Isochrone or Isochron ous Curve (F. Courbe [or Ligne] Isochrone; G. Isochrone or Gleacjizeitenkurve), that is a curve down which a particle may descend under the action of any assigned forces so as to describe equal vertical spaces in equal times. For construction of points of the curve see figure.

3. Cissoid of Diodes (F. Cis soide de Diocles; G. Kissoide des Diokles), or 2asin 2 0 cos 8, a curve in vented by Diocles (c. Too B.e.) to solve the problem of the duplica tion of the cube. The area between the curve and its asymptote is three times that of the generating circle. Its polar reciprocal with respect to a circle with centre at its cusp is a semi-cubical parabola. OP = BC, OA = 2a ; see fig.

4. Strophoid (F. Strophoide; G. Strophoid), if oblique (F. oblique; G. skriige), (a— 28)/sin was first con sidered by Barrow (167o). When a=9o° the strophoid is right replaces the cone we get a right strophoid.

5. Folium of Descartes (F. Folium de Descartes; G. Cartes isc/ies Blatt or Descartessches Blatt), = 3axy, a curve with asymptote x+y+a=o, first discussed by Descartes in 1638 (see fig.). The Hessian Curve of a folium of Descartes is another folium of Des cartes.

6. Trisectrix of Maclaurin (F. Trisec trice de Maclaurin; G. Maclaurins Tri sektrix), or or r=asec9-4acos8 = 2asin39/sin2 0 (see fig.), first studied by Maclaurin (1742) who showed that it could be used to solve the problem of trisection of an angle. Re ferred to the focus ( — 2a, o) as origin the polar equation of the trisectrix may be written r = a/cos . Maclaurin noted that the curve goes over into a folium of Descartes by an affine trans formation, showing that the gen eral shape of the two curves is the same.

7. Witch of Agnesi or V ersiera (F. Versiera or Agnesienne or Courbe d'Agnesi; G. Versiera or Agnesische K u r v e ), = (a—y), discussed, and named versiera, by Maria Agnesi (1748), but earlier treated by Fermat (before i 6 6 6 ), and Grandi (1703) who also named it ver siera. The area between the curve and its asymptote y = o is four times that of the generating cir cle. If each of the ordinates of the versiera be doubled, we get the Pseudo Versiera (locus of = (2a — y) first treated by J. Gregory (1658), and later dis cussed by Leibniz (1674) in de riving his formula 7r/4= —1/3 +1/5+1/7+ . . . . (See the figure.) 8. Serpentine (F. Serpentine or anguinee; G. Serpentine or Schlangenkurve) =o(ab>o) (see fig.), associated with the name of Newton who called it anguinea. L'Hos pital and Huygens recognized (1692) that the serpentine could be used as an auxiliary for rectification of the logarithmic curve. Consider the intersection of a cylinder of revolution and a hyperbolic paraboloid with a common tangent plane intersecting the hyperbolic paraboloid in (F. droite; G. gerade), r = a cos 26/cos 9 or = (a — x) (a x) (see fig.). Let g be the generator of a circular cone and t a tangent perpendicular to this generator. Any plane, p, through t will intersect the cone in a conic. The locus of the foci of the conics as p rotates about t, is a strophoid (Casali, 1757); if a cylinder two lines (one of them a generator of the cylinder) making an angle of 45° with one another at the point where the intersection of the planes of symmetry of the surface meets it. The curve of section is a horopter (F. Horoptere; G. Horopterkurve) dis covered in his studies in physiological optics by Helmholtz (1867, Eng. trans. vol. 3, 1925) and whose projection on the tangent plane is a versiera, and on a plane of symmetry through the axis perpendicular to this plane is a serpentine. The tangents to the horopter intersect the plane, through the point of contact of the tangent, perpendicular to the axis, in a cardioid.

9. Trident of Newton or Parabola of Descartes (F. Trident de Newton or Parabole de Descartes; G. Newton's Tridens or Car tesische Parabel). Trident is the name applied by Newton (I 7oi ) to the cubic curve xy = f one form of which is indicated in the figure. Newton observed that exactly this curve was used by Des cartes (1637) to construct a curve of the sixth degree; hence the name Parabola of Descartes.

Io. Cartesian or Cartesian Ovals (F.

Cartesienne or Ovales de Descartes; G.

Cartesische Kurve or Cartesische Ovalen) have been studied by many mathematicians such as Descartes (1637), Newton, Quete let, Chasles, Cayley, Darboux (for bibli ography see Bull. Sc. Math. (2) v. 6, 1882, pp. 40-49 and L'In term. d. Math., v. 3, 1896, p. 239). The Cartesian is the locus, two ovals, of points, P, whose distances from two fixed points (foci, distance c between them) satisfy a linear non-homogeneous rela tion or a linear homogeneous relation = o, where is the distance of P to a third focus collinear with the other two (Chasles, 1837). Hence the equation in rectangular co-ordinates may be written: [ (x2+y2) (I — + — = . When m= ± I the locus be comes an ellipse or hyperbola as it should; when m = we get the Limacon of Pascal for which two foci coalesce at the node.

For different forms of Cartesians see Cay ley, Coll. Math. Papers, v. 2, pp. 374.

27. Cayley's Sextic (F. Sextique de Cayley; G. Cayley's Sextik), or first found by Maclaurin (1718), and indeed as a cardioid pedal, was so named because a detailed study of the curve was first given by Cayley.

28. Watt's Curve (F. Courbe de Watt;

G. Watt'sche Kurve) is the sextic curve generated by a point P of the side BC of a three-bar linkage AB, BC, CD, the points A and B remaining fixed while the others vary (see fig.). If 0 is the middle point of AD, and AO = a, AB = CD = b, BP =PC = c, the polar equation of the locus of P is [asin9± — 6) 1 ] 0 varying from o to ir. If the end of a piston rod is fastened at P to the bar BC it will move up and down approximately in a straight line ("parallel motion") while B and C describe circles. In 1784 this device was patented by James Watt, the inventor of the modern condensing steam-engine. Watt's curve becomes a lem niscate of Bernoulli when c = a, and b = For references to the extensive literature of Watt's curve see L'Interm. d. Math., v. 4, p. 184 seq., and Bull. d. Sc. Math., 1883, p. 145 seq.

29. Pearls of Sluze

(F. Perles de Sluze; G. Perlkurven). Pearls is the name (due to Pascal) of the curves studied by Sluze (165 7 58) and defined by the equation yn = k (a — x) /'xm, where m, it, and p are positive integers. The cubical parabola and the pear shaped quartic are special cases considered by Sluze and Huygens in the course of considerable correspondence connected with pearls of Sluze.3o. Lame Curves (F. Courbes de Lame or Storoides; G. Lame'sche Kurven) is the name applied to the family (x/a)n-{-(y/b)ft= i, discussed by G. Lame (1818), which are algebraic when n is rational, and transcendental otherwise. Par ticular cases are: parabola (n=1), cross curve (n= —2), evolute of a central conic (n = i), and astroid (n=4, a = b). Lame curves with the same exponent, and tangent to one another at the same point P, have the same radius of curvature at P (Fouret, 189o). A number of other general results have been found, and many varieties of the curves considered.

2i. Rhodoneae (F. Rhodonacees or rliodonees or rosaces; G. Rosenkurven), curves r=acosk 0 or r=asink8, so named by Guido Grandi (1723, 1728) because of their fancied resemblance to roses. They are epitrochoids generated by a circle of radius (k—I)a/2(k+I) rolling on a circle of radius ka/(k+i), the generating point of the rolling circle being distant a from its centre. When k is an integer there are k or 2k petals of the rose curves according as k is odd or even. When k is rational there are a finite number of petals, and when k is irrational, an infinite number. When k=3 we have the Tri f olium; k= 2, the Quadri f olium (F. Quadrifolium; G. Quadrifolium or Vierblatt) a sextic curve r=acos29, or (x2-1-y2)3=a2(x2—y2)2 (see fig. no. 26); k= I, the first positive focal pedal of the cardioid. The inverse of a Rhodonea is an Epi [ear, as of corn] (G. Ahrenkurve) The polar reciprocal of an epicycloid or a hypocycloid with respect to a circle concentric with the base circle is an epi. This curve is also one of Cotes's Spirals whose pedal equation is which occur as the path of a particle projected in any manner under the action of a central force varying as the inverse cube of the distance. There are five cases : A= o, loga rithmic spiral; B=I, hyperbolic spiral; according as = (1/a2) ± — do we have rsinhn e= 0, rcoshn 9=a. These five cases are discussed by Cotes in his Harmonia Mensurarum, 1722, pp. 30-35. But rcoslin 8 = a de fines what is usually known as Poinsot's Spiral (F. Spirale de Poinsot; G. Poinsot'sche Spirale) which is mentioned by this eminent geometer as a herpolhode in his celebrated "new theory," of the rotation of bodies.

32. Curve of Pursuit (F. Courbe [or Ligne] de Poursuite or Courbe du Chien; G. Verfolgungskurve or Hundekurve). If a point A describes a known curve, the curve described by a point P, the motion of which is always directed towards A, A and P moving with uniform velocities, is a curve of pursuit. If A moves along a straight line, which may be taken, as the Y-axis, the equation of the locus of P is found to be of the form

if m>i or m

If the point A moves on a circle (Math. Monthly, v. i,

p.

the problem is much more difficult and does not seem to have been finally solved till 1921 (Amer. Math. Mo., v. 28, pp. 54, 91, 278). The discussion leads to a quadrifolium. The problem of three dogs placed at the vertices of an equilateral triangle and starting simultaneously with equal velocities, to chase one another, led to the logarithmic spiral as the curve of pursuit for each dog (Noun. Corresp. Math. v. 3,

pp.

28o). This problem is generalized in Johns Hopkins Univ. Circ., 1908, p.

33. Epicycloid, Hypocycloid (F. Epicycloide, Hypocycloide; G. Epizykloide, Hypozykloide). The epicycloid (hypocycloid) is the curve traced out by a point on the circumference of a circle which rolls without slipping on the exterior (interior) of a fixed circle. If a is the radius of the fixed circle, b the radius of the rolling circle, and h the distance from its centre of the tracing point, the equations of the epicycloid may be written (if h is if b < a. But if b> a, they correspond once more to equations of an epicycloid; and indeed any epicycloid defined by (I) can also be generated by a circle rolling with internal contact on the outside of a fixed circle, e.g., the cardioid (see fig., no. 25). There is a similar double generation of every hypocycloid, a fact first noticed by Daniel Bernoulli (1725). If a : b is a rational number the curves are algebraic and unicursal, e.g., the cardioid, nephroid, tricuspid and astroid; otherwise they are transcendental.

When h is not equal to b the curves are Epitrochoids, Hypotro choids (F. .pitroclzoides, Hypotrochoides; G. Epitrochoiden, Hypotrochoiden) which, for h < b, are curtate epicycloids (F. ac courcies or raccourcies; G. verkiirzte) and, for h>b, prolate (F. allongees or rallongees; G. gestreckte or gedehnte or geschweifte). There is a double generation, by rolling circles, of epitrochoids and hypotrochoids. If b = 4-a, and h+ b, the hypotrochoid is an ellipse (W. Wallace, 1839) ; when h = b, the point traces out the diameter of the fixed circle (Nasir Eddin, about 125o), a result of importance in connection with certain machines. The limacon of Pascal is an example of both a curtate and prolate epitrochoid. When in (I) h = a+ b we get the equation of a rhodonea, which is always an epitrochoid or hypotrochoid (Suardi, 1752; Ridolfi,

The artist Albrecht Diirer seems to have been the first (1525) to have considered a special case of an epicycloid. In the 17th century LaHire, Desargues, Leibniz, Reaumur and Newton con tributed to knowledge concerning the curves; among other things Newton showed (Principia) that all epicycloids and hypocycloids are rectifiable.

Apart from general references given below see E. Wolffing's biblio graphy, Bibl. Math. (2) , (i 9oi) and R. A. Proctor, Cycloid and ... Cyctoidal Curves (London, 1878) ; and for many other beautiful forms of cyclic curves see C. Taylor, Curves Formed by the Action of . . . Geometric Chucks, 2 vols. (London,

; T. S. Bazley, Epicycloidal Cutting Frame (London, 1872) ; and R. E. Moritz, Cyclic Harmonic Curves (Univ. Wash. Pubis. in Math., 1923).

34. Bowditch Curves or Lissajous Curves (F. Courbes [or Fig ures] de Lissajous ; G. Lissajous-Kurven or Lissajoussche Kurven) .

These are curves defined by the equations x=asin(miu+ni), y=

or x = asin (nt+c), y= bsint (i). The curves evidently do not lie outside a rectangle whose sides are tangents and whose ver tices are (±a, ±b). The curves are alge braic and unicursal when n = p/q (p < q ) is rational and transcendental when n is irrational. Such equations, in effect, and corresponding curves seem to have been first studied by Nathaniel Bowditch, author of the well-known book on naviga tion, in connection with the motion of a pendulum suspended from two points (1815, Mem. Amer. Acad., v. 3). The study was suggested by a paper on the apparent motion of the earth as viewed from the moon. When p = q the Bowditch curves are a series of concentric ellipses. If p/q = I we obtain a curve of the fourth order (is c

with one double point, and a parabola (if c =o).

Two forms of these curves as well as three forms for the case p/q= s (all given by Bowditch) are indicated in the figures. For other forms see Geiger and Scheel, Handbuch d. Physik, v. 8 (Ber lin, 1927) and Melde, Lehre von d. Schwingungskurven (Leipzig, 1864). These curves are also met in acoustics; an approximation to some of the curve forms having been given by Thomas Young (Phil. Trans., i800). They were, however, studied in detail by Lis sajous (1857-58) whose name was consequently connected with them. They occur, thirdly, in discussion of geodesic lines on Liou ville surfaces (Enzyk. d. Math. W iss., v. 3, pt. 3, 1927). And finally they are members of a group of curves studied by W. F. Rigge (Harmonic Curves, Omaha, Neb., 1926, the Hagen pendulum illus trations being especially interesting) . If with equations (I) we consider z = bcost we have that every Bowditch curve is the ortho gonal projection of a sine curve developed on a right circular cylin der (see Handbuch, l.c.). For Lissajous curves in space see Melde (1.c.), E. H. Comstock and C. S. Slichter (Trans. Wisconsin Acad., v. II, [ 1898 ] ) , and Zambiasi, Le figure di Lissajous (19°3) .

35. Sinusoidal Spirals (F. Spirales Sinusoides; G. Sinus-spi ralen), rn = a"cosn6, where n is a positive or negative rational number. Particular cases are : line (n = — 1), circle (n= I), parab ola (n= — - ), equilateral hyperbola (n= —2), lemniscate of Bernoulli (n= 2) , cardioid (n = 1) , logarithmic spiral (n = o, Haton de la Goupilliere, 1857), Cayley's sextic (n=), and Tschirnhausen's cubic (n= --I) first shown by Tschirnhausen (169o) to be a catacaustic of a parabola for rays perpendicular to its axis of symmetry. This curve has also been called cubique de l'Hospital, and Trisektrix von Catalan. The equation of this curve as well as those of all other nodal cubics such as the strophoid, trisectrix of Maclaurin, and folium of Descartes, can be expressed in the form X I + Y3 +Z = o, where X, Y, Z are linear functions of x and y which when set equal to zero are the equations of tangents at the points of inflection of the cubic. Sinusoidal spirals were first studied by Maclaurin (1718, 17 2o) who showed : (a) that their positive and negative pedals are again sinusoidal spirals; (b) that a body will trace out a sinusoidal spiral if acted on only by a force, in the direction of the pole, in versely proportional to the power 2n+3 of its distance from the pole. For example, the lemniscate of Bernoulli is traversed by a body acted on by force directed to the double point and inversely proportional to the seventh power of the distance of this point from the moving body.

36. Cycloid (F. Cycloide; G. Cykloide or Zykloide or Rad linie),

one of the most celebrated of all special curves, is the locus of a point on the circumference of a circle rolling along a straight line (see fig. A). Its Cesaro intrinsic equation is R2+s2

where a is the radius of the rolling circle. Sir Christopher Wren discovered (1658) that the length of a single arch is four times the diameter of the generat centre of the rolling circle the equations of the locus are: x = a9 +hsin

y = a — hcose , which define Trochoids which are (h

37. Euler's Spiral or Clothoid or Cornu's Spiral (F. Clothotide or Spirale de Cornu or Spirale de Fresnel; G. Klothoide) is the curve defined by the equations with asymptotic points at (±

-- a7ri/2g), and hence the name clothoid suggesting the spinner among the Fates (see fig.). The intrinsic equation of the curve is Rs =

showing that the radius of curvature of any point of the curve is inversely proportional to the length of arc to that point from some point of reference. All of these results (for half the curve) were found by Euler in his Methodus inveniendi lineas curvas ... , (1744) and in a paper presented to the Academy at St. Petersburg in 1781 wherein he determined the asymptotic points. The curve originated in the consideration of an elastic spring. The similar problem of an elastic lamina was considered earlier (1694) by Jacques Bernoulli but there is no indication that he had any con ing circle. Its area above the base line is three times that of the generating circle, a result approximated by Galileo Galilei (c. 1599) on weighing pieces of paper cut in the forms of the circle and cycloid (a name given by Galilei). But the first exact deriva tion of the area was due to Roberval (1634). The discovery by Huygens (1673) that the evolute of a cycloid is an equal cycloid led to his construction of the isochronal pendulum (see no. 2) generally known as the cycloidal pendulum. The cycloid is a tautochrone (Huygens, 1673) and a brachistochrone (Jean Ber noulli, 1696, see nos. 48, 56). In 1639 Galilei recommended the form of the cycloid for arches of bridges.

If the tracing point

of the rolling circle generating the cycloid be not on the circumference but at a distance ji. from the ception, as Euler had, of the real form of the curve. In the 19th century, through discoveries by Fresnel in connection with the diffraction of light, Euler's spiral, and integrals (for which there are many tables) became of special interest.

Euler's spiral is advocated by many writers as a Transition Curve for railways ; see, for example, A. L. Higgins, The Transi tion Spiral (London, 1921). For different values of m the in trinsic equation Rsm =

represents a clothoid, a logarithmic spiral, the involute of a circle, and a straight line. For a bibliog raphy of Euler's spiral see Amer. Math. Mo., v. 25, pp. 276-282.

38. The family of curves

= a'nO, for which the pedal equa tion is p2(m2r2m+a2m) =m2r2m+2 (Sacchi, 1854) includes four notable curves: (a) Spiral of Archimedes (m=1) (F. Spirale d'Archimede; G. Archimedisclie Spirale) ; (b) Fermat's Spiral (m = 2) ; (c) Hyperbolic [or Reciprocal] Spiral (m= —I) (F. Spirale Hyperbolique; G. Hyperbolische Spirale) ; (d) Lituus (m = —2) (F. Lituus or Trombe; G.

Lituus or Krumrnstab) .

(a) This spiral, r = a 8, in which the length of the radius vector is proportional to the angle, is discussed at length in the book on spirals by Archimedes (c. 225 s.c.) and it seems that it was used by him to solve the problem of squaring the circle. The subnormal of the spiral is always equal to a. Archimedes gave, in effect, the quadrature of the curve, as

/6 (see fig.) . The spiral is the pedal of the in volute of a circle with respect to its centre (Maxwell, 1849). The orthogonal projection of the line of section of a helicoid and a cone of revolution with coincident axes, on a plane perpendicular to the axis, consists of two equal spirals of Archimedes (Pappus, c. 33o; see F.G.IMI., Exercices de Geom. Descr., 4th ed., Tours, 1909, p. 811, seq.).

(b) The spiral

= ate was dis cussed by Fermat (1636) and has the form in the figure. Its inverse with respect to its pole is a lituus.

(c) The hyperbolic spiral, r 8= a, the consideration of which originated with Varignon (1704), was also studied in the 18th century by Jean Bernoulli (1710-13)

and Roger Cotes (1722). The subtangent of the curve is of

stant length, a. If through a point P (r, 6) of the hyperbolic spiral r9=a, a line PP", of length r, be drawn parallel to the axis, the locus of

is a cochleoid. The conical projection of a helix, from a point of its axis, on a plane perpendicular to the axis is a hyperbolic spiral (T. Olivier, 1833) .

(d) The lituus,

=

originated in a study by Cotes (1722) of the curve which is the locus of the point P moving in such a manner that the area of the circular sector POp (see fig.) com prised between OX and OP remains constant.

39. Involute of a Circle (F. Developpante du cercle; G. Kreis evolvente) is the roulette of a point, P, on a straight line which rolls on a circle cen tre 0 (see fig.). Its pedal equation with respect to 0 is

=

its Whewell in trinsic equation

and its Cesaro in trinsic equation

= 2as. Its parametric equations are x = a (cos0-{-0 sin ck ), y = a (sin4 —ccos4). The involute of a circle is the locus of the pole of a logarithmic spiral rolling on a concentric circle (Maxwell, 1849) . The involute of a circle seems to have been conceived in 1693, when Huygens was considering clocks without pendulums which might be of service on sea-going vessels (Huygens, Oeuvres, v. 10. 1905, p. 514). In this connection he originated an apparatus in which the involute plays an essential role. In 1891 it became desirable to enlarge the dome of the Royal Observatory at Green wich ; for various reasons the new dome was made, for the most part, in the form of a surface generated by the revolution of an arc of an involute of a circle (Mo. No. R. Astr. So., v. 51).

40. Cochleoid [snail form] (F. Cochleoide; G. Kochleoide or Schneckenhauslinie or Schraubenkurve) , r = asin 010 (see fig.), was first considered as a quadra trix of a circle in an anonymous paper in the Phil. Trans. (17oo) . The curve was' considered again in correspondence of Goldbach and Daniel Bernoulli (1726) as the locus of the ends of equal arcs measured from the common point of contact of a series of tangent circles. The points of contact of parallel tangents to the cochleoid lie on a strophoid hav ing the pole for double point (Teixeira, 1909). The projection of a cylindrical helix from one of its points on a plane perpendicular to its axis is a cochleoid.

41• Logarithmic [or Equiangular or Logistic] Spiral (F. Spirale Logarithmique [or .quiangle or Logistique] ; G. Logarithmische Spirale) was first discussed by Descartes (1638), in connection with a problem in dynamics, as the curve cutting radii vectores from a fixed point 0 under a constant angle 4). If P (r, 9) is any point on the curve and s is its length from 0 to P, Descartes observed that s = rconst., and hence rectified a curve for the first time (see no. 2) . Loria claims this honour for Torricelli (Accad. d. Lincei, Rendiconti cl. d. sc. fisiche, matem. e nat. v. 6 (2), 1897, p. 318). The intrinsic pedal and polar equations of the curve are : R = as, p = rsin .95, and r = kece (1) where c = cot 4. The form of the curve depends on c and is wholly independent of k. The lengths of radii vectores making equal angles with one another are in geometric progression. That the pole was an asymptotic point seems to have been first noticed by Torricelli (1646). Collins (1675), and Jacques Bernoulli, to whom the name logarithmic spiral is due ("equiangular spiral" originated with Cotes, 1714), noticed (1691) the analogous generations of this spiral and of the loxodrome, and that the latter is a ster eographic projection of the former seems also due to Collins, although the result was first published by Halley (1696) . Among theorems given by Bernoulli (1691-93) are the following: the pedal of a logarithmic spiral with respect to its pole is a loga rithmic spiral ; its evolute is an equal spiral with the same asymp totic point; its catacaustic for rays emanating from the pole as luminous point is an equal spiral. The discovery of such "per petual renascence" delighted Bernoulli, who requested that the spiral be engraved on his tomb with the inscription Eadem rnutata resurgo. That an attempt was made to grant the re quest may be seen at his tomb in the cloister of the cathedral at Basle. If the surface generated by the revolution of a lo garithmic curve about its asymptote intersect a helicoid with the asymptote as axis the orthogonal projection of the curve of section of the surface on a plane perpendicular to the axis is a logarithmic spiral (Chasles, 1837). Sir John Leslie seems to have been the first (1821) to suggest, what was later estab lished, that the septa of the nautilus are in form logarithmic spirals. The curve has also been discussed in connection with ar rangements of florets in sun-flowers, pine cones and other growths. The most complete historical summary of the extensive literature of the logarithmic spiral is given by R. C. Archibald in an appen dix to J. Hambidge, Dynamic Symmetry (New

192o).

42. Frequency Curve or Probability Curve or Normal Curve of Errors (F. Courbe de Probability or Courbe de Possibilite; G. Wahrscheinlichkeitskurve or Fehlerkurve) is the name usually applied to the bell-shaped curve whose cartesian equation is y= (a/ rri)

(I) . This curve originated, in essence, with DeMoivre (1733, see Isis, v. 8, p. 671 seq., and Biometrika, v. 16, p. 402 and v. 17, p. 201), although it has been connected more particularly with the names of Laplace and Gauss (see Trans. Connecticut Acad., v. 4). The equation has been de veloped on various hypotheses the statement of which may be found in works on probability and statistics. Among many tables giving the area, ordinate, and other information, for such curves as the particular case of (I), when a =11, m=1, are J. W. Glover's, Tables of Appl. Math. (1923) . The term Frequency Curves is applied to a great variety of curves ; see, for example, W. P. Elderton, Frequency Curves and Correlation, 2nd ed.

43. Logarithmic [or Logistic] Curve (F. Logarithmique or Logistique; G. Logarithmische Kurve [or Linie] or Exponen tialkurve, or Logistika) is the curve defined by the equation x = alog (y/m) or y = me x/a and consisting of a single branch (for a summary of considerable discussion in this regard see Salmon, Higher Plane Curves, 3rd ed., p. 286) with the axis of X as asymp tote (see fig. in no. 44, locus of P,, where m=a). The curve originated with a problem and discussion about 1640 and then and later in the 17th century (that of the discovery of loga rithms) in connection with the names of Torricelli, James Gregory, Craig, Huygens and others. The characteristic property of the curve as then found was : whatever m may be, the subtangent is constantly equal to a (see fig.). The area between the curve, the asymptote and an ordinate is equal to that of a rectangle with sides respectively equal to the abscissa and subtangent (Torricelli, Huygens).

44. Catenary or Chainette (F. Chainette; G. Kettenlinie) is the form (Galilei thought it a parabola) which a perfectly flex ible, inextensible chain will assume when suspended by its ends and acted upon by gravity alone. Its equation, determined in 1691 by such mathematicians as Huygens and Leibniz, can be written y= 4a (ex/a+e-x/a) =acosh (x/a). Points on the curve may be readily determined from logarithmic curves (see fig.). The tangents at P,

P2 are concurrent. If s represents the length of the catenary measured from its vertex on the Y-axis to any point P,

=

-1-

and s = asinh (x/a) . The Cesaro in trinsic equation is aR =

which is a particular case of the equation

which defines curves named by Cesaro (1886) Alysoid (F. Alysoide; G. Alyseiden). If two opposite edges of a thin inextensible and perfectly flexible rectangular piece of cloth are fixed parallel to each other, and the cloth is exposed to a uniform current of air moving at right angles to the plane which contains the two fixed edges of the cloth the form of equilibrium of the cloth (which is the form of the cross section of a sail filled by wind) is a catenary, or, as Jean and Jacques Bernoulli (1692-95) called it a Velaria (sail curve, G.

Segelkurve or Seilkurve). If the catenary is revolved about the X-axis we obtain a catenoid, which is the only minimal surface of revolution, a surface discussed by Euler as early as

and illustrating important principles in the calculus of variations.

Since a catenary may be regarded as a roulette of the focus of a parabola rolling along a straight line, it has been called also a parabolic catenary. Similar roulettes of an ellipse and of a hyperbola lead to an elliptic catenary and a hyperbolic catenary. The corresponding surfaces of revolution are called respectively Unduloid and Nodoid (see A. G. Greenhill, Elliptic Functions, 1892). Delaunay showed (1891) that surfaces of revolution of constant mean curvature are of the three types here mentioned.

45. Tractrix or Tractory or Equitangential Curve (F. Trac trice or Tractoire or Courbes aux Tangents Egales; G. Zug linie or Traktrix or Traktorie) being equitangential (PN =a, see fig.) is defined by the equations y(I

=

or

) and y=asinu; and

In 1692 Huygens considered this curve in detail and hence the name Traktorie von Huygens has been used ; it was later studied, among others, by Leibniz and Jean Bernoulli. The tractrix (see fig.) is the orthogonal trajectory of circles of radius a with centres on the X-axis (Liouville, 185o). The evolute of the tractrix (locus of P), is the catenary (locus of Pi) The projection N, of

on the X-axis is the end of the tangent PN, which is constantly equal to a. The intersecting surface of constant negative curvature generated by revolving the tractrix about its asymptote is called a pseudosphere (Beltrami, 1865), and its volume is one half that of the sphere of radius OC = a (Huygens, 1692). The "surface of Dini" is a helicoid with the tractrix as meridian curve (Dini, 1865).

If on the tangent PN to the tractrix a point P2 is taken (see fig.) such that

= b, a constant, the locus of P2 as P traces out the tractrix is the Syntractrix (F. Syntractrice; G. Syntrak trix) defined by

i=alog{

l]/y}, and whose intrinsic equation, when b= 2a, may be written R= (a/4) (es/a+e-s/a).

This equation differs but slightly from R = (a/2)

which defines a Catenary of uniform strength (F. Chainette d'Egale Resistance; G. Kettenlinie gleichen Wiederstandes or Longitudinale). Thomson and Tait give the equation of this curve (Nat. Phil., §573; also Coriolis, 1836), in which linear den sity or cross section is so arranged as to be proportional to the ten sion, as eY/a =sec (x/a), which may be written tanh+(y/a) =

The curve was first discussed by Gilbert (1826) in his memoir on suspension bridges. It is the curve which with its catacaustic, for parallel rays, encloses the minimum area (Dun kel, Washington Univ. Studies, v. 8, 1921).

46. Quadratrix of Hippias (F. Quadratrice de Dinostrate; G. Quadratrix des Dinostratus), y=xcot(7rx/2a), rsin9— (2a/7r)6, a curve invented by Hippias of Elis (c. 43o B.c.) and used (by him, apparently) for trisecting an angle (it may be used for dividing an angle into any number of equal parts), but also employed (as the name implies) for squaring the circle. Hippias may have used the curve for this purpose. Sometimes the curve is called the Quadratrix of Dinostratus since he seems to have used it as a quadratrix (c. 35o B.c.) . Suppose OA = a, the radius of the circle with center 0 (see figs.), rotates uniformly to the position OC at the same time that a straight line through A, parallel to the Y-axis, moves uniformly toward the axis, the two lines coinciding with OC at the same time. The locus P of their point of intersection is the quadratrix of Hippias (Pappus, c. 300) ; OD = 2a/lr. Pappus showed that it is an orthogonal

projection of a certain plane section of a helicoid. See fig., p.

47. Anallagmatic Curve (F. Courbe anallagmatique; G. Anall agamatische Kurve, Unverdnderliche Kurve), first discussed by Moutard (1864), is a curve Which inverts into itself (cf. Proc. Edinb. Math. Soc., v. 20). The inverse of any curve possessing a line of symmetry is, in general, anallagmatic. Since bicircular quartics (which include the limacon, cardioid, cartesian, cassinian), as well as the strophoid, the trisectrix of Maclaurin and the cissoid, are the inverses of conics, they are thus anallagmatic. In par ticular, the cartesian is anallagmatic with respect to any of its foci, the power of inversion being the product of the distances of this focus to the other two foci; for the strophoid its vertex is the centre of inversion, and the power of inversion is the square of the distance of the vertex to the double point ; so also for the trisectrix of Maclaurin. The inverse of an anallagmatic curve is anallagmatic.

48. Brachistochrone (F. Brachistochrone or Brachystochrone; G. Brachistochrone or Linie schnellsten Falles) is the curve along which a body moves from one point A to another B, under the action of an assigned accelerating force, in the least time possible. The problem when gravity was the accelerating force was proposed by Jean Bernoulli (1696) as a challenge to mathematicians. Leib niz, Newton, Jacques Bernoulli, and L'Hospital responded with solutions, that the curve was a cycloid. That there is one and only one cycloid arc with the required property was not shown till the i9th century, when an important necessary condition, unstated by Bernoulli, and other things in the theory of the calculus of variations, were formulated. A sinusoidal spiral, = a'tcosn8, is a brachistochrone :or a repulsive force varying inversely as the power 2n-3 of the radius vector (Townsend, 1875). See Appell, Traits de Mec. Rat., V. 2, 3rd ed. (19o9), p. 460, seq.

49. Caustic (F. Caustique; G. Kaustik or Brennlinie). If a ray of light from some source is incident on a curve, the reflected ray will make with the normal to the curve at the point of incidence the same angle as that made by the incident ray. The envelope of the reflected rays is the Caustic by Reflection or Catacaustic of the given curve with respect to the source in question. If the ray, corresponding to an incident ray from some source, makes with the normal to the curve at the point of incidence an angle whose sine is in a constant ratio to the sine of the angle which the incident ray makes with the normal (Snell's law of refraction, before 1626), the envelope of the refracted rays is called the Caustic by Refraction or Diacaustic of the given curve for the source in question. Catacaustic and diacaustic surfaces may be defined in a similar way. The diacaustic of a straight line, 1, with respect to a source, S, is the evolute of an ellipse with foci at S and the reflection of S in 1 (Gergonne, 182o). The diacaustic of a circle is, in general, the evolute of a cartesian (Sturm, 1824). If the source is at an infinite distance the incident rays are parallel. The idea of caustic curves originated with Huygens and Tschirnhausen about 1678 and was developed, among others, by Jean and Jacques Bernoulli and by L'Hospital before the end of the century. About 1822 it was discovered by Quetelet that the caustic (C'), of a given curve (C), for a finite source S, is the evblute of a curve (C"), called Secondary Caustic, which is the envelope of the circles with centres on (C) and passing through S; or the evolute of a curve (C"), which is similar to the pedal of (C) with respect to S, but of double its linear dimensions. Some samples of special curves as catacaustics are as follows: See F. Bosser, Zeit. f. Math. u. Phys., v. 15, pp. 170-206; Geiger and Scheel, Handbuch d. Physik, v. 18 (1927) ; R S. Heath, Treatise on Geometrical Optics (1887) ; Brocard and Lemoyne's work mentioned below ; G. F. Childe, Reflected Ray Surfaces . . . (Cape Town,

bibliography in L'Intermed. d. Math. (1894), p. 19o, and

pp. 208, 321.

50. Evolute (F. Developpee; G. Evolute or Kriimmungsmittel= punktslinie or -kurve). This is the envelope of all the normals to a curve of the locus of the curve's centres of curvature. A curve and its evolute have the same foci. The deficiency of the evolute is the same as that of the primitive curve. For other general properties of such curves see Salmon, Higher Plane Curves, 3rd ed., 1879, p. 82 seq. Evolutes of Epicycloids and Hypocy cloids (e.g., cardioid, nephroid, tricuspid, astroid) are curves of the same type. So also for the cycloid and logarithmic spiral, but the evolute of a parabola is a semi-cubical parabola; of a trac trix, a catenary; of a Cayley's Sextic, a nephroid.

If the evolute be regarded as the original curve, a curve of which it is the evolute is called an Involute (F. Developpante; G. Evolvente or Involute) ; or an involute of a curve is an or thogonal trajectory of the tan gents to the given curve. There are an infinite number of such trajectories for any given curve, and they are Parallel Curves (F. Courbes Paralleles; G. Parallel kurven) ; that is, any two cut off equal lengths on common nor mals. Parallel curves sometimes have a very different appear ance, for example, Cayley's Sex tic and the nephroid. The accom panying figure shows : (a) two parallel curves, 3, 4, of an astroid, 2, one of them an oval, and also (b) the evolute, 1, of this astroid.

The conception of evolutes and involutes originated with Huy gens in his celebrated Horlogium Oscillatorium (1673). The principles underlying the determination of such envelopes, as well as those connected with caustics by Tschirnhausen (1682), were developed into a theory by Leibniz (1692-94), who was the first to consider parallel curves.

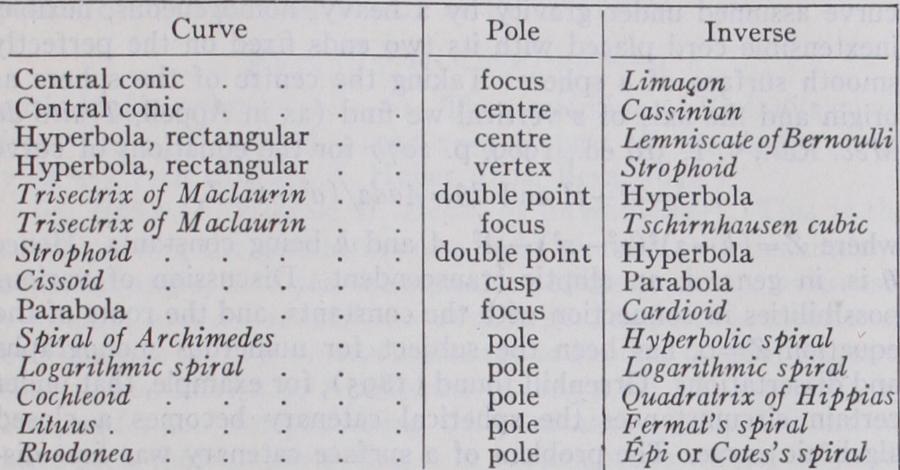

51. Inverse Curves (F. Courbes Inverses; G. Inverse Kurven).

If through a point 0, called the centre of inversion, a line is drawn to any point

of a curve C1, and on

a point P2 is taken such that OP1.OP2 =

a constant,

and P2 are inverse points. As

traces the curve Cl, P2 traces its inverse curve C2. If the power is —

the points

and P2 are on opposite sides of 0. The first examples of this transformation were given by Quetelet (1825). (See also no. 47.) Some examples of curves and their inverses are as follows: 52. Isoptic Curve (F. Courbe isoptique or Ligne isoptique; G. Isoptische Kurve or Kurve gleichen Gesichtswinkels). The locus of the points of intersection of tangents to a given curve (or a pair of curves) meeting at a constant angle is an isoptic curve of the given curve, or curves. When the constant angle is right the isoptic curve is said to be the Orthoptic Curve (F. Courbe Orthoptique; G. Orthoptische Kurve). The isoptic curve of an epicycloid is an epitrochoid (Chasles, 1837) ; of a cycloid a cur tate or prolate cycloid (LaHire, 1704) ; of a sinusoidal spiral another sinusoidal spiral. The orthoptic curve of a tricuspid is a circle ; of an astroid, a quadri f olium; and of a cardioid, a circle and a Limacon of Pascal, which suggests that the isoptic curve of Chasles's theorem should be one or more epitrochoids; indeed the number of such epitrochoids is only finite if the radius of the base of the given epicycloid is commensurable with that of the rolling circle (Duporcq, L'Interm. d. Math., 1896, p. 291). The orthoptic curve of two confocal conics is a concentric circle (Chasles) .

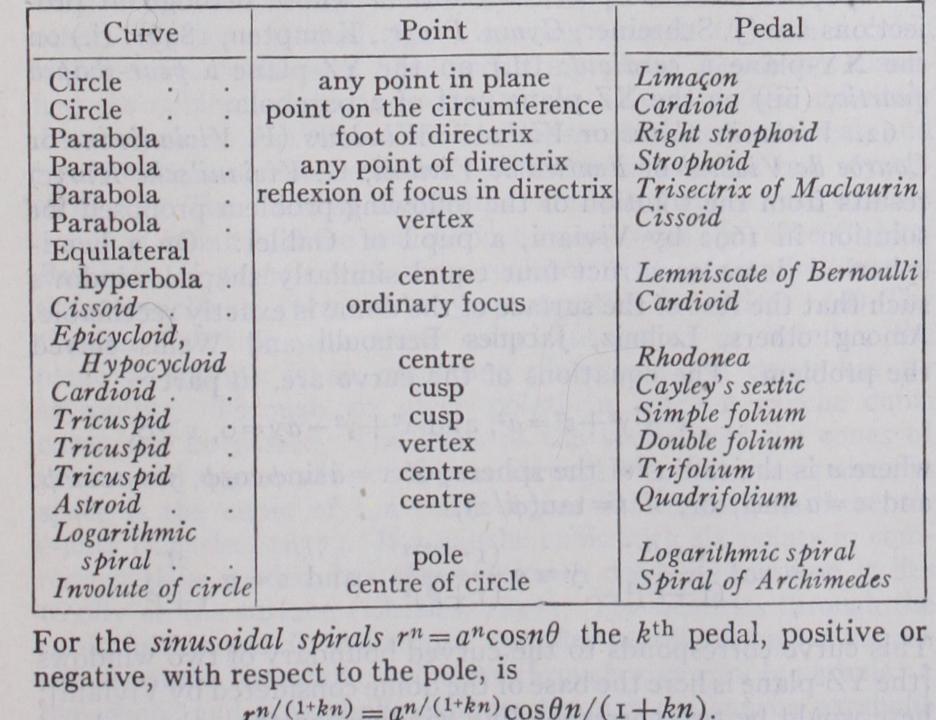

53. Pedal or Pedal Curve (F. Courbe pedale or Podaire; G. Fusipunktkurve). The pedal (CO of a curve (C), with respect to a point 0, is the locus of the feet of the perpendiculars from 0 on the tangents to (C). Maclaurin first introduced (1718) the idea of positive and negative pedals of a curve with respect to a point; (C1) is the pedal or first positive pedal of (C), or (C) is the first negative pedal of (CO. If (C2) is, with respect to the same point, the first positive pedal of (CO, it is the second posi tive pedal of (C) ; and so on. Some examples of pedals are as follows: From this, many results can be stated ; for example : the fifth negative pedal of a cardioid is a Tschirnhausen cubic; the fourth positive pedal of a parabola is a cardioid. The term tangential pedal curve is sometimes used to distinguish it from normal pedal curve where normals play the same role as tangents in the above discussion.

54. Radial or Radial Curve (F. Courbe radiale; G. Radiale) . From a fixed point lines are drawn equal and parallel to the radii of curvature at successive points of a given curve; the locus of the extremities of these lines is the radial curve corresponding to the given curve (Tucker, 1864) . The degree of the radial of an algebraic curve is that of the curve's evolute. The following are some examples (c =curve, r =radial) : c —catenary, r—kam pyle of Eudoxus; c—catenary of uniform strength, r —a straight line; c — tractrix, r—kappa curve; c—cycloid, r —circle, c — cycloid of n cusps, r—rhodonea of n petals; c —tricuspid, r — tri f

c — astroid, r — quadri f olium.

55. Roulette (F. Roulette; G. Rollkurve or Roulette). When a curve rolls, without slipping, on a fixed curve or straight line, any fixed point, P, in the plane of the rolling curve describes a curve called a roulette. The term is also sometimes applied (still limiting motion to that in a plane) to : (a) the envelope of a fixed line in the plane of the rolling curve; (b) the locus of a variable point, such as the centre of curvature of the point of contact of the rolling curve. If 0 is the point of contact of rolling and fixed curves, OP is normal at P (P, fixed) to the curve traced by P (Descartes). If any curve roll on an equal curve, corre sponding points of the curves being in contact, the roulette of any point is a curve similar to a certain pedal of the fixed curve and of double its linear dimensions (Maclaurin, 172o) ; in particular Cayley's Sextic is generated by the cusp of a cardioid rolling, with corresponding points in contact, on an equal cardioid (Mac laurin). The roulette of the vertex of a parabola rolling on a fixed equal parabola is a cissoid of Diocles. The cycloid, epicycloids, epitrochoids and hypocycloids are examples of roulettes. Every rhodonea can be generated as the roulette of a 'circle on a circle (Suardi, 1752, and Ridolfi, 1844). The hyperbolic spiral whose equation is r = a/9 rolled on a logarithmic curve whose equation is y =clog (x/a) traces the axis of y or the asymptote (Maxwell, 1849). The pole of a hyperbolic spiral rolling on a straight line traces out a tractrix (Demoulin, 1891). A helix rolls on a straight line to which it is always tangent while its axis moves in a plane; any point of the helix traces out a cycloid (Besant, 187o). Refer ences may be given to J. C. Maxwell's second published paper in 1849 (Scientific Papers, vol. i.) and to W. H. Besant's Notes on Roulettes and Glissettes (end ed., Cambridge, 189o). Among Glissettes (F. Glissettes; G. Gleitkurven) are the curves: (a) traced out by points, (b) enveloped by a fixed line, in the plane of a curve which is made to slide between given points, or straight lines, or curves, or to glide so as always to be tangent to a line at a fixed point. The envelope-glissette of a given line segment sliding between lines at right angles is an astroid. The point glissette of the focus of a parabola sliding between two lines at right angles is an epi or Cotes's spiral whose equation may be written

An involute of a circle slides on a straight line, always touching it at the same point ; the glissettes of a point and a straight line are respectively a trochoid and an involute of a cycloid (Besant) .

56. Tautochrone (F. Tautochrone or Courbe Tautochrone; G. Tautochrone or Gleichzeitkurve). This is a curve along which a particle acted on by assigned forces will arrive in the same time at a given point whatever initial point is taken on the curve. When gravity is the accelerating force Huygens showed (Hor logium Oscillatorium, 1673) that the inverted cycloid with axis vertical was the tautochrone. The converse problem was solved by Newton (Principia, 1687, bk. 3, sec. 1o). The problem of the tautochrone was notably discussed by Jean Bernoulli (1718), and Euler (1726-72), and Lagrange (1767, Oeuvres, V. 2, 1868, p.

The astroid is a tautochrone for a force perpendicular to a line and proportional to the cube root of the distance to this line (Jullien, 18 5 5) . The cardioid is a tautochrone for a repulsive force varying as the distance, situated on the axis at one-quarter of the distance from the focus to the vertex (Purkiss, 1864) . A

similar result holds for all epicycloids (Purkiss). (See C.

mann, Das Problem der Tautochronen; ein historischer Versuch.) 57. Clelies (F. Clelies; G. Cleliakurven or Clelien) . Let be

the longitude, and 0 the colatitude, of any point P on a sphere of radius a. If this point is moved such that 0 = mnc/), in being a constant, the locus described by P is a cic1ie, discussed by Guido Grandi (1728). When m = 1 we have Viviani's Windows. In Cartesian co-ordinates the equations may be written x = a sinm4 cos4, y = a sinmg5 sin4, z = a cosm4.

The projection of this curve on the XY-plane is the rhodonea,

Grandi applied the name clelies also to curves defined by the equations a sin

a sin

The projection of the first curve on the XY-plane is r = b sinm4 again a rhodonea. The projection of the second curve on the XY-plane is represented by the equation r = a— b sinm4 which is a conchoid of the same rhodonea.

58. Horse Fetter or Hippopede (F. Hippopede; G. Hippopede or P f erde f essel) is a term applied to two different curves dis cussed by the Greeks (cf. Heath, Hist. Greek Math., v. 1, pp.

v. 2, pp.

(a) The horse-fetter of Eudoxus (fl. c. 365 B.c.) is the curve described by a planet about the zodiac circle in his theory of concentric spheres, and it is the curve of section of a circular cylinder and tangent sphere (Schiaparelli, Scritti s. storia d. Astronomica Antica, part 1, t. 2, p. 4o seq.). Let the centre, 0, of the sphere, of radius, a, be the origin ; the axis of y the line through 0 and B, the point of contact of cylinder and sphere ; the axis of z parallel to the generator of the cylinder, then the equations of the horse-fetter are:

+ (y — b) 2 = (a — b)

where b is the distance of the axis of the cylinder from 0. Because of its form, the curve has been called a spherical lemniscate. Its projection in the YZ-plane is part of the parabola

2 by — 2ab = o. The YZ-plane and XY-plane are planes of symmetry and B is a double point. The stereographic projection of the horse-fetter with respect to the point (o, a, o) is the hyperbola (a — b)

—

= a

When b = a/ 2 the horse fetter, which Eudoxus introduced into geometrical discussion, becomes part of Viviani's curve.

(b) The plane curve hippopede, referred to by Proclus, appears to be one of the spiric lines of Perseus (c. 75 B.c,), that is one of the curves formed by a plane section of an anchor ring parallel to its axis. When the plane is tangent to the anchor ring internally, the section is a hippopede whose equation is

=

If the distance of the plane from the axis is equal to the radius of the generating circle of the ring (c = 2a) the hippopede is a lemniscate of Bernoulli.

59. Loxodrome or Rhumb Line or Spherical Helix (F. Loxo dromi-e; G. Loxodrome or Rhumblinie) is usually defined as the curve cutting the meridian of a sphere at a constant angle; it is a double spiral having the north and south poles for asymptotic points. The curve was first conceived by Pedro Nunes (155o). If the constant angle is 3, p is the longitude and 0 the colatitude of a point on the loxodrome its equation may be written x = sin0 cos 0, y = sink sin 0, z = cosq5, where 0= —tan33logtan(4/2). The orthogonal projection of this curve on the XY-plane is

= 2 or

where h = cotf3, Poinsot's Spiral (see no. 31) . The stereographic pro jection of a loxodrome from one of its poles on the plane of the equator is a logarithmic spiral. Nunes had the idea (not yet dead) that a loxodrome joining two points on a sphere was the shortest distance on the sphere between those points. Support of this view may have been found by some in the fact that on Mercator charts (1569) the spherical loxodrome becomes a straight line. In the i9th century intelligent mariners realized that great circle sailing should replace loxodromic paths for shortest dis tances. The most notable history of the loxodromic line is that of S. Gunther, Studien z. Gesch. d. Math. u. Phy. Geographic, pt. 6 (Halle, 1879).

The general question of loxodromes on any surface of revolu tion was studied for the first time by J. G. Walz in 174i. But Scheffers introduced the idea (1902) of a loxodrome as a space curve and not a surface curve, a curve which cuts all planes of a pencil under a constant angle. Loxodromes are space W-curves of Klein and Lie (1870) ; see Enzykl. d. Math. Wiss., v. 3, p.

6o. Spherical Catenary (F. Chainette Spherique or Catenaire Spherique; G. Sphdrische Kettenlinie). (a) This is the form of a curve assumed under gravity by a heavy, homogeneous, flexible, inextensible cord placed with its two ends fixed on the perfectly smooth surface of a sphere. Taking the centre of the sphere as origin and the axis of z vertical we find (as in Appell, Traite de Mec. Rat., v. 1, 3rd ed., 1909, p. 207) for the equations of curve

and

where Z=

A and h being constants. Hence 0 is, in general, an elliptic transcendent. Discussion of various possibilities in connection with the constants, and the roots of the equation Z=o, has been the subject for numerous monographs and dissertations. Greenhill found (1895) , for example, that under certain circumstances the spherical catenary becomes a closed algebraic curve. The problem of a surface catenary was first dis cussed by Bobillier (1829) for any surface.

(b) Gudermann defined a spherical catenary by the equation tan0= coshm4, without any reference to mechanics but simply from analogy with the equation of the plane catenary curve (Grundriss d. analyt. Sphdrik, 183o and Crelle's Journal, v. II, 1834). He showed that this catenary is an evolute of the spherical loxodrome

61. Spherical Epicycloid (F. Epicycloade Spherique; G. Sphd rische Epizykloide). This curve is the locus of a point on the circumference of a circle which rolls on the circumference of a fixed circle, the plane of the rolling circle always making with that of the fixed circle a constant angle, w. These curves were first studied by Hermann (1728) as a result of a problem pro posed in 1718 by Offenbourg: To construct on the surface of the sphere a window with contour algebraically rectifiable. (It would seem as if the problem had been suggested by that of Viviani's windows, no. 62.) Hermann's mistake in imagining all such curves rectifiable was pointed out by Jean Bernoulli (1742) and the only possible case for this was indicated. Clairaut, Gudermann and Lexell were other workers in this field. (See H. M. Jeffrey, Quart. bourn. Math., v. 19, 1883, p. 44 seq.) The equations of such curves may be written x = acos0— b [I —cos(a0/b)]coswcos0+asin(a0/b)sin0, y = asin0— b [1—cos(a0/b)]coswsin0—asin(a0/b)cos0, z= a [1—cos(a0/b)]sinw, and define spherical curves, algebraic and unicursal if a/b is rational, and transcendental if a/b is irrational. If a = b and w = 7r/2, we have a Spherical Cardioid whose orthogonal pro jections are (J. Schreiner, Gymn. Progr., Kempten, 1896) : (i.) on the XY-plane a cardioid; (ii.) on the YZ-plane a pear-shaped quartic; (iii.) on the XZ-plane part of a parabola.

62. V iviani's Curve or Viviani's Windows (F. Vivianienne or Courbe de Viviani or Fenetre de Viviani; G. Viviani'sche Kurve) results from the solution of the following problem proposed for solution in 1692 by Viviani, a pupil of Galilei: On a hemi spherical dome construct four equal similarly shaped windows such that the rest of the surface of the dome is exactly rectifiable. Among others, Leibniz, Jacques Bernoulli and Wallis solved the problem. The equations of the curve are, in part: the hemispheres. The area of the hemisphere left is

The orthogonal projection of Viviani's curve on the XZ-plane is half of the eight curve,

=

—

and on the YZ-plane is a portion of the parabola

= a(a —y). The stereographic projection of Viviani's curve on: (I) the XZ-plane and with the point (o, a, o) as pole is half of the equilateral hyperbola 0—

(2) on the XZ-plane with the point (o, — a, o) as pole is half of the lemniscate of Bernoulli

(3) on the XY-plane with the point (o, o, a) as pole is part of the strophoid

—

with double point at (o, a, o). The projection of Viviani's curve from (o, o, o) on the plane z= a is part of the kappa curve

=

(See T. Huber, Diss. Bern, 1916.) 63. Helix (F. Helice; G. Helix, or Schraublinie). This is the curve cutting the generators of a right circular cylinder under a constant angle, 0. Then the equations of the curve are x = a cos 8, y = a sin 9, and z= a 6 cott3 ; s= a e cosec13. The helix is mentioned by Geminus (c. 7o B.C.) and a passage in Proclus (c. 46o) suggests that it was known to Apollonius (c. 225 B.c.) . It was used by Pappus (c. 300) for producing the quadratrix of Hippias and we have seen that by projecting it in various ways we get a cycloid a trochoid, a cochleoid and a hyperbolic spiral. Its orthogonal projection on a plane parallel to the axis of the cylinder is a sine curve (Pitot, 1724). The ratio of the radii of curvature and torsion of the helix is constant (Lancret, 5802). Puiseux found (1842) that the only curve for which the radii of curvature and torsion are constant is the right circular helix. The helix is a special case of Bertrand Curves for which a linear relation between curvature and torsion exists. A moving straight line always meeting a helix and intersecting its axis orthogonally traces out a right circular helicoid which is the only real minimal ruled surface (Catalan, 1842).

The curve which cuts the generators of a cone of revolution under a constant angle is a Cylindro-Conical Helix or Conica Loxodrome (F. Helice cylindro-conique or Spirale logarithmique conique; G. Zylinderkegelschraubenlinie) and was first discussed by Guido Grandi (I 7o 1) . Its equation may be written Grandi noted that this helix cuts also under a constant angle the generators of a cylinder,of which one generator coincides with the axis of the cone and whose base is a logarithmic spiral having its pole on this axis. A certain logarithmic spiral on the XY-plane, and with pole at the origin, is an involute of Grandi's helix (1826) .

64. Cubical Conic Sections (F. Coniques Cubiques; G. Ku bische Kegelschnitte), which may be obtained as the line of in tersection of two cones of thy. second order, or of two hyperboloids of one sheet, with a common generator, was first discussed by Mobius in his Der barycentrische Calcul (Leipzig, 1827), and later studied by Chasles (2837), Cayley (2845), Cremona (186 2) and others. Mobius showed that a moving tangent to such a cubic traces out a conic on a fixed osculating plane. Seydewitz classi fied the cubics (1847) according to the nature of their infinitely distant points : (a) The Cubical Ellipse which has one real, and two conjugate points at infinity ; this curve has one real asymp tote. ( b) The Cubical Hyperbola which has three real distinct points at infinity; three real distinct asymptotes. (c) The Cubical Parabolic Hyperbola with three real points at infinity but two of them coincident; three real asymptotes, two coincident. (d) The Cubical Parabola with three coincident points at infinity ; the plane at infinity is an osculating plane and the curve has no asymptote. Through six given points in space . gauche cubic curve can be passed. The locus of the vertices of the cones of the second degree which all pass through the six given points in space is the cubic of the third degree determined by these six points (Chasles, 1837). If a gauche cubic with six points in com mon with a quadric has also a seventh point in common it lies wholly on the surface (Chasles, 1857). The quadrics through the cubic form a pencil. An elliptic cylinder passes through a gauche ellipse; three hyperbolic cylinders through a gauche hyperbola; a hyperbolic and a parabolic cylinder through the gauche parabolic hyperbola; and a parabolic cylinder through the gauche parabola. The numerous results found for such cubics are summarized in Ency. d. Sc. Mathem., t. 4 v. 4, pt. I, Paris, 1914, p. 119 seq. See also 0. Staude, Kubische Kegelschnitte (Leipzig, 1913), and P. W. Wood, The Twisted Cubic with some account of the Metri cal Properties of the Cubical Hyperbola (1913) . Interpretations of the invariants and covariants of a binary cubic in terms of the geometry of a twisted cubic are given in Grace and Young, Algebra of Invariants (1903).

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-The

principal general sources are: F. G. Teixeira, Bibliography.-The principal general sources are: F. G. Teixeira, Traite d. Courbes Spec. Remarquables, 3 v. (Coimbre, 1908-15), also in Obras s. Math., v. I, 2, 7; G. Loria, Spezielle algeb. and transz. ebene Kurven, 2nd ed., 2 v. (Leipzig, 1910—II) ; G. Loria, Curve Sghembe Speciali, 2 V. (Bologna, 1925) ; G. Brocard, Notes de Bibl. des Courbes Geometriques, 2 v. (lithogr., Bar-le-Duc, 1897-99) ; H. Brocard and T. Lemoyne, Courbes Geometriques Remarquables, v. I (all publ.) (5959) ; Enzyklopadie d. math. Wiss., v. 3, parts 2 and 3 (Leipzig, 1902 27) ; H. Wieleitner, Spez. ebene Kurven (Leipzig, 1908) ; Pascal-Tim erding, Repertorium d. hoh. Math., Geometrie, 2 ed., 2v., (Leipzig, 1910-22). (R. C. A.)