Table Cutlery

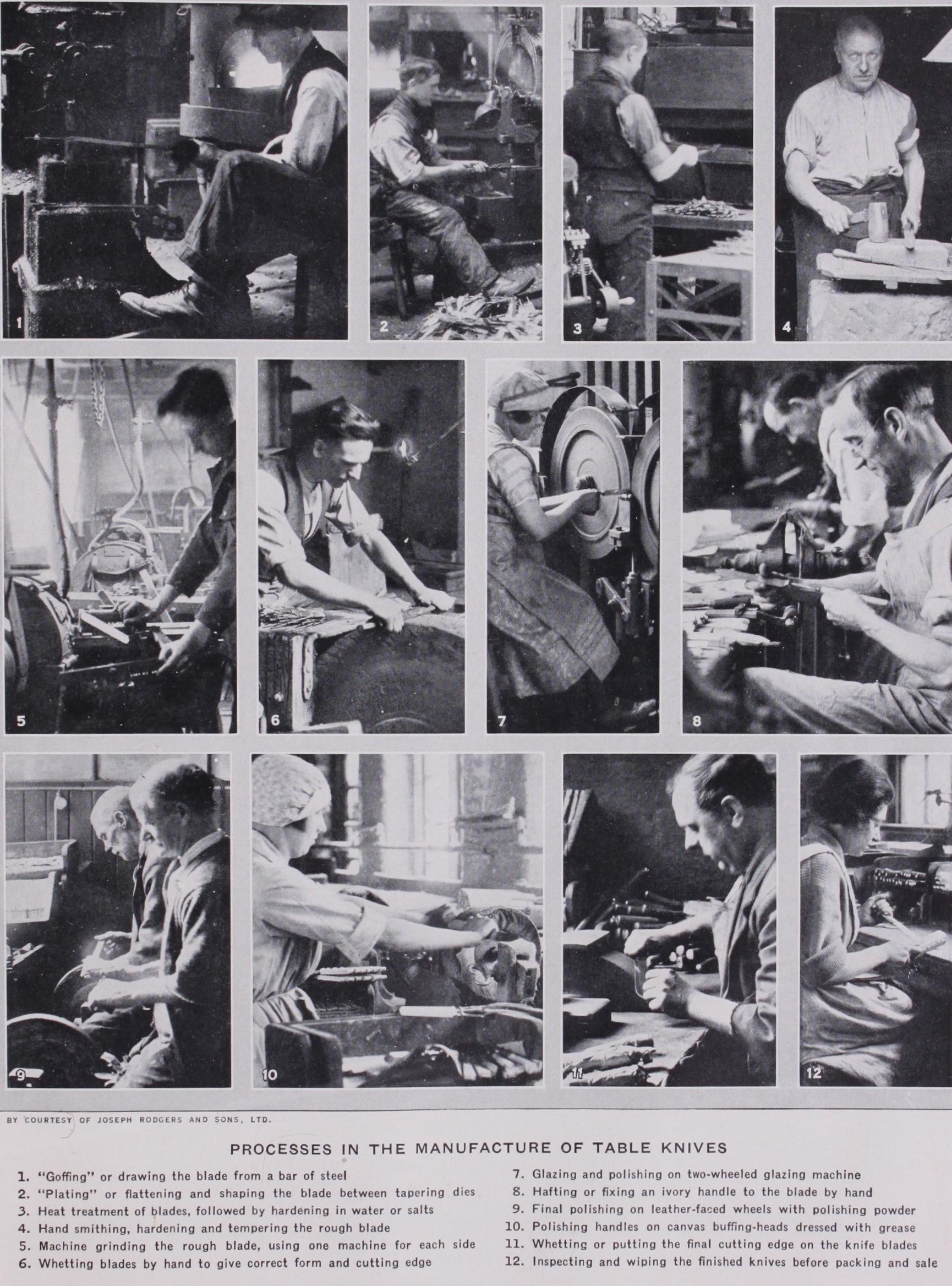

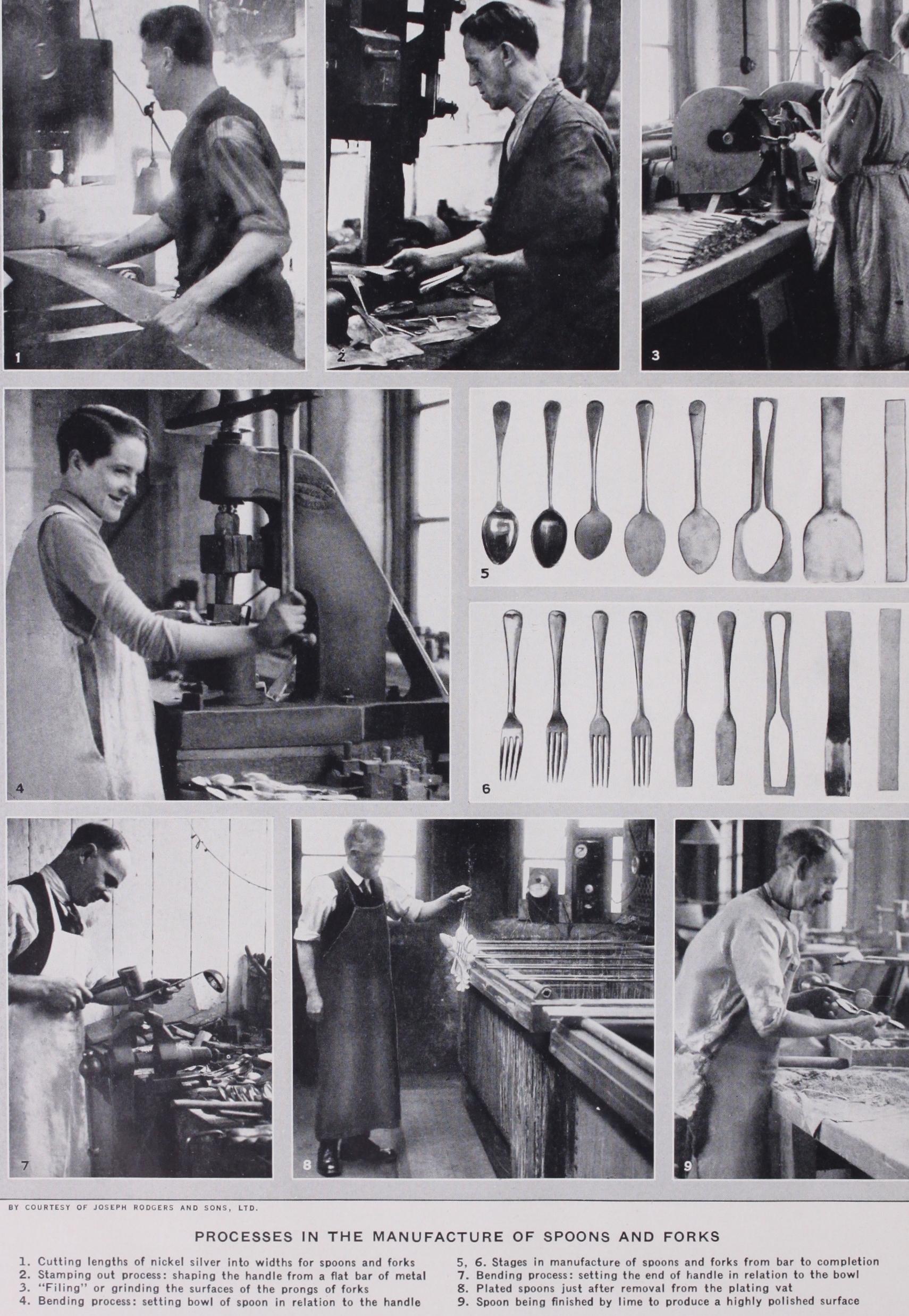

TABLE CUTLERY The production of blades for table cutlery is accomplished in three successive stages: the first consisting of forging the steel into the desired shape, the second in grinding the steel to a cutting edge and imparting a polish to the steel, and the third in finishing the blade and fitting the handle.

Forging.—The better quality of knives are hammered by ma chinery from short, square bars of good steel. The blade receives many hundreds of blows in being forged down to the desired pat tern. This hammering, like the old hand-forging, it is claimed, imparts to the blade the valuable quality of resisting wear and retaining a sharp cutting edge.

A shoulder or "bolster" is usually forged, or rolled, at the handle end of the blade, and the forging is continued below the bolster to form the "tang" or prolongation of the blade for inser tion into the handle.

The introduction of machinery into the forging processes in volved in table-knife forging has had the effect of creating in Sheffield a new subsidiary trade called "the golfing trade." Hardening and Tempering.—Af ter the blades are forged or cut out they are hardened by heating in a suitable furnace to the correct temperature and then quenched, that is, immersed in a cooling liquid. The temperature of heating required for the "stainless" steel is higher than that required in the case of other steels, the temperature of heating being in the one case 174o° F and in the other i400° F before quenching. Various mediums are used for quenching purposes, water being the one most com monly adopted. After hardening, the blades are very brittle and are much too hard for regular use. They are then tempered by re heating to a low temperature (39o° F) and again quenched. This latter treatment gives the blades the right amount of toughness combined with hardness.

A number of interesting instruments for obtaining the exact measure of hardness of the material have been introduced.

Grinding.—The blade is now subjected to the next stage, that of grinding. Machinery has largely superseded craftsmen in the grinding of table-knives; there are, however, many hand-grinders employed in Sheffield, Solingen and Thiers. In a few cases they use the same equipment driven by a water-wheel, which was in use more than a century ago. Prior to 1914 the grinders used exclusively a sandstone grinding-wheel for grinding down the forged blade to a knife blade having an even, fine cutting edge, and having a back of increasing thickness from the point of the blade to the handle. This caused a fine dust from the grind stone, and although in most cases it was saturated with water it was extremely injurious to the lungs of the grinder and resulted in a disease known as "silicosis." This injurious effect upon the health of the workman is recognized by the British Government, which requires the payment by the employer of compensation under certain conditions.

The grindstones from 5 f t. to 6ft. in diameter, when new, are made to revolve in a trough containing sufficient water to wet the surface of the grindstone. In some cases the sandstone has been replaced by an artificial abrasive wheel which has the ad vantage of being a "healthy" wheel, but the cost unfortunately is many times the cost of the sandstone.

The grinders use the wheels differently in various centres. In Sheffield they sit on a "horsing" which is mounted over the wheel, and the men exert a pressure of the work on the wheel by stand ing up slightly and putting the weight of the body on the work. In Solingen the wheel is made to revolve in front of the grinder, whilst in Thiers the men lie flat on boards placed over and behind the grinding wheels. In all cases the wheels revolve so that the periphery moves away from the worker and not towards him.

After the grinding operation has been completed the blades are fitted with handles. A wide range of material is used for the handles, varying from ivory or silver in the most expensive knives to wood in the very cheap knives. The material which is most popular in Europe is celluloid, whereas in the United States preference is given to the solid steel handle.

Carvers are made up in sets consisting of knife, fork and steel for sharpening the knife. The carving fork is the sole remaining example of the old steel forks used formerly with the table knives. The fork is provided with a guard made in various de signs to prevent the blade from cutting the hand during use.

Another form of kitchen knife is the "bread knife." Some of these knives are made with a wavy edge, others are made with saw teeth cut into the finished knife, the object being to be able to cut newly-baked bread.

Table cutlery has been recently extended to include a small knife, generally made in fancy patterns with coloured handles, called a "tea knife." It is popular in cafes, where it is frequently used when eating pastries.

Pocket Knives.—The production of pocket knives commenced with the "Jack" knife, and at first was confined to heavy knives containing one blade which would open and close into a groove in the handle. Later a spring was used to secure the blade in both positions. Pocket knife manu facture is therefore known as "spring knife" cutlery. Then other blades were introduced, and the knife containing a small blade at one end and a larger blade at the other end became known as the "pen knife," due to the use of the smaller blade for sharpen ing quill pens.

Pocket knives are made in a great variety of patterns, some firms alone offering them in a thousand different forms. The more expensive are finished by jewellers, the cutlers supplying the skeleton knife without the covering. The jeweller then com pletes the knife by fitting gold scales, and some of these are even inlaid with precious stones.

The fitting of the spring knife calls for highly skilled work, as the slightest variation in the length of the spring, or the joints, will affect the correct position of the blade when open or shut.

The blades of pocket knives are made from high-grade steel, and they are tempered slightly harder than table knives, this operation calling for much skill.

The pocket knife which is fitted with a variety of articles, such as corkscrew, pricker, scissors, etc., is known as a "sporting knife." This type of knife lends itself to many extreme uses, for example a pocket knife made for an engineer includes a foot fold ing rule, calipers and screw-driver, in addition to the blades.

Razors.—Razors are of very remote origin, and their manu facture is carried on in most cutlery centres. The finest steel is used for the blades, which are most accurately ground and care fully whetted to produce the fine shaving edge. The hollow ground razor is made in various patterns known as "full hollow," "three-quarter hollow," and "half hollow." The full-hollow razor is ground to an extremely thin part about the middle of the blade and is increased in thickness towards the edge, finally tapering off to the cutting edge. The essential qualities of the blade are its proper hardness and its extremely fine cutting edge.

Many attempts have been made in the past to introduce safety devices for razors, but it was not until the advent of the "Gillette" razor that this problem was satisfactorily solved, and later other types have been successfully introduced.

The safety razor consists of a small blade secured by a holder and to which is fitted a guard. The guard keeps the edge of the blade from coming into actual contact with the skin. It is, how ever, possible for a careless individual to cut himself even with this precaution, especially if he tries to use it at a wrong angle or uses the corner of the blade. The safety blade is of simple form; straight of edge, and lends itself to production by machine methods, eliminating most of the grinding required for ordinary hollow-ground razors. On the other hand, the safety blade in use must be kept clean. The blades, unless exceptional care is taken, require renewing frequently. To avoid this expense a stropping device is included in some patterns.

The principle of fitting a guard has been extended and applied to the ordinary hollow-ground razor, thus converting the plain razor into a safety razor. Another pattern of safety razor adopts the hollow-ground Made of the ordinary razor using a small section of this blade.

Scissors.—Scissors are largely produced by forging the two parts in drop stamps from a milder quality of steel than is used for razors or pocket knives. The parts are "dressed up" and "put together," and, in order to prevent the scissors from working loose, the screw which holds them together is tightly fitted and made from hard steel. There are two interesting features of fitting scis sors, the first is that the blades are slightly bent towards each other, so that they make a close contact on the cutting edge, and in addition there is provision made in the joints for ensuring this contact.

Scissors are sometimes made with shaped bows so that the thumb and fingers can operate with more ease. These shaped scissors are sometimes produced from malleable castings and the blades made from steel are later fitted to the castings. Another process is to die-cast the parts in aluminium and fit steel blades to them, the latter possessing the advantage of being very light and of having an attractive appearance. There are many types of household scissors in addition to dressmaking, embroidery and manicure patterns, whilst for trade purposes there are scis sors made for tailors, weavers, gardeners, cattle marking and many others. Many forms of cutting instruments cannot be strictly defined as domestic articles, such as knives for kitchen purposes, paper knives, and knives for shoemakers, painters, and many other trades.

The Craftsman.—One of the most interesting features of the cutlery trade is the survival of some of the old guild conditions, particularly in Sheffield. The practice of dividing the trade into three sections of forging, grinding and finishing still continues.

It is in the grinding section particularly that many old customs are maintained. The workmen in some cases work at communal factories, called tenement factories, or "wheels," which are put up for the purpose of obtaining rents from any grinder who de sires accommodation. The grind er pays rent and he obtains a trough in which he fits his grind ing wheel, and in addition he is supplied with power to drive it and light. In some factories a small weekly charge is made for light.

The craftsmen are in many cases free to go and return from work at any time to suit their own convenience. They work for any employer who will provide them with work, but as there is no contract of service they are prevented from coming within the provisions of certain factory legislation, such as the Work men's Compensation Act.

In the early days of cutlery manufacture, both in England and on the Continent, guilds or companies of cutlers were estab- - lished, the object being to protect the trade, maintain the quality of production and regulate the conditions under which the trade was carried on, including the number and training of apprentices. Some of these companies became very powerful and exerted con siderable influence over the welfare of the trades.