The Crusades of St Louis

THE CRUSADES OF ST. LOUIS The Seventh Crusade.—As the loss of Jerusalem in 1 187 produced the third crusade, so its loss in 1244 produced the seventh : as the preaching of the fifth crusade had taken place in the Lateran council of 1215, so that of the seventh crusade began in the Council of Lyons of 1245. But the preaching of the crusade by Innocent IV. at Lyons was a curious thing. On the one hand he repeated the provisions of the Fourth Lateran Coun cil on behalf of the crusade to the Holy Land ; on the other hand he preached a crusade against Frederick II., and promised to all who would join the full benefits of absolution and remission of sins. While the papacy thus bent its energies to the destruction of the crusades in their genuine sense, and preferred to use for its own political objects what was meant for Jerusalem, a layman took up the derelict cause with all the religious zeal which any pope had ever displayed. Paradoxically enough, it was now the turn for the papacy to exploit the name of crusade for political ends, as the laity had done before; and it was left to the laity to champion the spiritual meaning of the crusade even against the papacy. It was at the end of the year in which Jerusalem had fallen that St. Louis had taken the cross, and by all the means in his power he attempted to ensure the success of his projected crusade. He sought to mediate, though with no success, between the pope and the emperor ; he descended to a whimsical piety, and took his courtiers by guile in distributing to them, at Christmas, clothing on which a cross had been secretly stitched. He started in 1248 with a gallant company, which contained his three brothers and the sieur de Joinville, his biographer; and after wintering in Cyprus he directed his army in the spring of 1249 against Egypt. The objective was unexpected : it may have been chosen by St. Louis, because he knew how seriously the power of the sultan was undermined by the Mamelukes, who were in the very next year to depose the Ayyubite dynasty, which had reigned since 1171, and to substitute one of their number as sultan. Damietta was taken without a blow, and the march for Cairo was begun, as it had been begun by the legate Pelagius in 1221. Again the invading army halted before Mansura (Dec. 1249) ; again it had to retreat. The retreat became a rout. St. Louis was captured, and a treaty was made by which he had to consent to evacuate Damietta and pay a ransom of 800,000 pieces of gold. Eventually he was released on surrendering Damietta and paying one-half of his ransom, and by the middle of May 125o he reached Acre, having abandoned the Egyptian expedition. For the next four years he stayed in the Holy Land, seeking to do what he could for the establishing of the kingdom of Jerusalem. He was able to do but little. The struggle of papacy and empire paralysed Europe, and even in France itself there were few ready to answer the calls for help which St. Louis sent home from Acre. The one answer was the Shepherds' crusade, or crusade of the Pastoureaux —"a religious Jacquerie," as it has been called by Dean Milman. It had some of the features of the Children's crusade of 1212. That, too, had begun with a shepherd boy : the leader of the Pastoureaux, like the leader of the children, promised to lead his followers dry-shod through the seas ; and tradition even said that this leader, "the master of Hungary," as he was called, was the Stephen of the Children's crusade. But the anti-clerical feeling and action of the Shepherds was new and ominous; and moved by its enormities the Government suppressed the new movement ruthlessly. None came to the aid of St. Louis; and in 12J4, on the death of his mother, Blanche, the regent, he had to return to France.

The Mameluk`es.

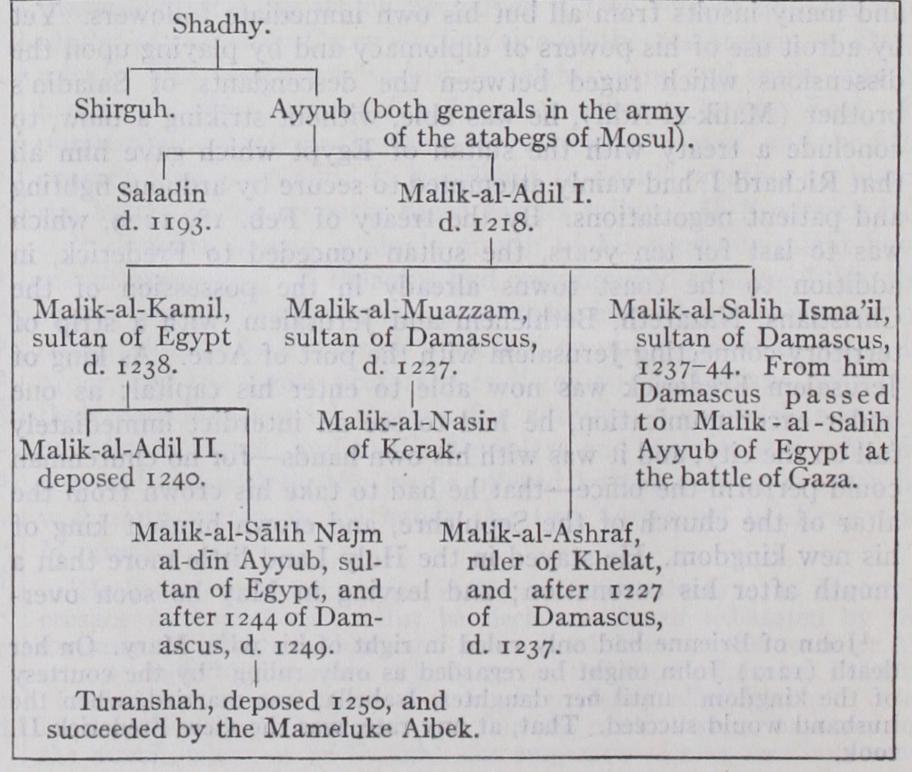

The final collapse of the kingdom of Jerusalem had been really determined by the battle of Gaza in 1244, and by the deposition of the Ayyubite dynasty by the Mame lukes. The Ayyubites had always been, on the whole, chivalrous and tolerant : Saladin and his successors, Malik-al-Adil and Malik al-Kamil, had none of them shown an implacable enmity to the Christians. The Mamelukes, who are analogous to the janissaries of the Ottoman Turks, were made of sterner and more fanatical stuff ; and Bibars, the greatest of these Mamelukes, who had com manded at Gaza in 1244, had been one of the leaders against St. Louis in 125o, and became sultan in 126o, was the sternest and most fanatical of them all. The Christians were, however, able to maintain a footing in Syria for 4o years after St. Louis' departure, not by reason of their own strength, but owing to two powers which checked the advance of the Mamelukes. The first of these was Damascus. The kingdom of Jerusalem, as we have seen, had profited by the alliance of Damascus as early as 1130, when the fear of the atabegs of Mosul had first drawn the two together; and when Damascus had been acquired by the ruler of Mosul, the hostility between the house of Nureddin in Damascus and Saladin in Egypt had still for a time preserved the kingdom (from 1171 onwards). Saladin had united Egypt and Damascus; but after his death dissensions broke out among the members of his family' which more than once led to wars between Damascus and Cairo. It has already been noticed that such a war between Malik al-Kamil and his rivals accounts in large measure for the success of the sixth crusade; and it has been seen that the battle of Gaza (1244) was an act in the long drama of strife between Egypt and northern Syria. The revolution in Egypt in 1250 separated Da mascus from Cairo more trenchantly than they had ever been separated since 1171: while a Mameluke ruled in Cairo, Malik-al Nasir of Aleppo was elected as sultan by the emirs of Damascus. But an entirely new and far more important factor in the affairs of the Levant was the extension of the empire of the Mongols during the 13th century. That empire had been founded by Jenghiz Khan in the first quarter of the century; it stretched from Peking on the east to the Euphrates and the Dnieper on the west. Two things gave the Mongols an influence on the history of the Holy Land and the fate of the crusades. In the first place, the south-western division of the empire, comprising Persia and Ar menia, and governed about 1250 by the Khan Hulaku or Hulagu, was inevitably brought into relations, which were naturally hostile, with the Mohammedan Powers of Syria and Egypt. In the second place, the Mongols of the 13th century were not as yet, in any great numbers, Mohammedans; the official religion was "Shamanism," but in the Mongol army there were many Chris tians, the results of early Nestorian missions to the far East. This 1 The following table of the Ayyubite rulers serves to illustrate the text:— last fact in particular caused western Europe to dream of an alliance with the great khan "Prester John," who should aid in the reconquest of Jerusalem and the final conversion to Chris tianity of the whole continent of Asia. The crusades thus widen out, towards their close, into a general scheme for the Christian ization of all the known world'. About 1220 James of Vitry was already hoping that 4,00o knights would, with the assistance of the Mongols, recover Jerusalem; but it is in 1245 that the first definite sign of an alliance with the Mongols appears. In that year Innocent IV. sent a Franciscan friar, Joannes de Piano Carpini, to the Mongols of southern Russia, and despatched a Dominican mission to Persia. Nothing came of either of these missions ; but through them Europe first began to know the in terior of Asia, for Carpini was conducted by the Mongols as far as Karakorum, the capital of the great khan, on the borders of China. Again in 1252 St. Louis (who had already begun to ne gotiate with the Mongols in the winter of 1248-49) sent the friar William of Rubruquis to the court of the great khan ; but again nothing came of the mission save an increase of geographical knowledge. It was in the year 126o when it first seemed likely that any results definitely affecting the course of the crusades would flow from the action of the Mongols. In that year Hulagu, the khan of Persia, invaded Syria and captured Damascus. His general, a Christian named Kitboga, marched southwards to attack the Mamelukes of Egypt, but he was beaten by Bibars (who in the same year became sultan of Egypt), and Damascus fell into the hands of the Mamelukes. Once more, in spite of Mongol inter vention, Damascus and Cairo were united, as they had been united in the hands of Saladin; once more they were united in the hands of a devout Mohammedan, who was resolved to extir pate the Christians from Syria.

While these things were taking place around them, the Chris tians of the kingdom of Jerusalem only hastened their own fall by internal dissensions which repeated the history of the period preceding 1187. In part the war of Guelph and Ghibelline fought itself out in the East ; and while one party demanded a regency, as in 1243, another argued for the recognition of Conrad, the son of Frederick II., as king. In part, again, a commercial war raged between Venice and Genoa, which attracted into its orbit all the various feuds and animosities of the Levant (1257). Beaten in the war, the Genoese avenged themselves for their defeat by an alliance with the Palaeologi, which led to the loss of Constan tinople by the Latins (1261), and to the collapse of the Latin empire after 6o years of infirm and precarious existence. On a kingdom thus divided against itself, and deprived of allies, the arm of Bibars soon fell with crushing weight. The sultan, who had risen from a Mongolian slave to become a second Saladin, and who combined tie physique and audacity of a Danton with the tenacity and religiosity of a Philip II., dealt blow after blow to the Franks of the East. In 1265 fell Caesarea and Arsuf ; in 1268 Antioch was taken, and the principality of Bohemund and Tan cred ceased to exist. In the years which followed on the loss of Antioch several attempts were made in the West to meet the progress of the new conqueror. In 1269 James the Conqueror of Aragon, at the bidding of the pope, turned from the long Spanish crusade to a crusade in the East in order to atone for his offences against the law matrimonial. An opportune storm, however, gave the king an excuse for returning home, as Frederick II. had done in I2 2 7 ; and though his followers reached Acre, they hardly dared venture outside its walls, and returned home promptly in the beginning of I 2 70. More serious were the plans and the attempts of Charles of Anjou and Louis IX., in which the cru sades may be said to have finally ended, save for sundry dis jointed epilogues in the i4th and 15th centuries.

The Eighth Crusade.—Charles of Anjou had succeeded, as a result of the long "crusade" waged by the papacy against the Hohenstaufen from the Council of Lyons to the battle of Taglia 'Though Europe indulged in dreams of Mongol aid, the eventual results of the extension of the Mongol empire were prejudicial to the Latin East. The sultans of Egypt were stirred to fresh activity by the attacks of the Mongols; and as Syria became the battle-ground of the two, the Latin principalities of Syria were fated to fall as the prize of victory to one or other of the combatants.

cozzo (1245-68), in establishing himself in the kingdom of Sicily. With the kingdom of Frederick II. and Henry VI. he also took over their policy—the "forward" policy in the East which had also been followed by the old Norman kings. On the one hand he aimed at the conquest of Constantinople as Henry VI. had done before; and by the Treaty of Viterbo of 1267 he secured from the last Latin emperor of the East, Baldwin II., a right of eventual succession. On the other hand, like Frederick II., he aimed at uniting the kingdom of Jerusalem with that of Sicily; and here, too, he was able to provide himself with a title. On the death of Conradin, Hugh of Cyprus had been recognized in the East as king of Jerusalem (1269) ; but his pretensions were opposed by Mary of Antioch, a granddaughter of Amalric II., who was prepared to bequeath her claims to Charles of Anjou, and was therefore naturally supported by him. But the policy of Charles, which thus prepared the way for a crusade similar to those of 1197 and 1202, was crossed by that of his brother Louis IX. Already in 1267 St. Louis had taken the cross a second time, moved by the news of Bibars' conquests ; and though the French baronage, including even Joinville himself, refused to follow the lead of their king, Prince Edward of England imitated his ex ample. Louis had been led to think that the bey of Tunis might be converted, and in that hope he resolved to begin this eighth and last of the crusades by an expedition to Tunis. Charles, as anxious to attack Constantinople as he was reluctant to attack Tunis, with which Sicily had long had commercial relations, was forced to abandon his own plans and to join in those of his brother. St. Louis had barely landed in Tunis when he sickened and died, murmuring "Jerusalem, Jerusalem" (Aug. 12 70) ; but Charles, who appeared immediately after his brother's death, was able to conduct the crusade to a successful conclusion. Negotiat ing in the spirit of a Frederick II., and acting not as a crusader but as a king of Sicily, he not only wrested a large indemnity from the bey for himself and the new king of France, but also secured a large annual tribute for his Sicilian exchequer. So ended the eighth crusade—much as the sixth had done—to the profound disgust of many of the crusaders, including Prince Ed ward of England, who only arrived on the eve of the conclusion of the treaty. Baulked of any opportunity of joining in the main crusade, Edward, after wintering in Sicily, conducted a crusade of his own to Acre in the spring of 1271. For over a year he stayed in the Holy Land, making little sallies from Acre, and negotiating with the Mongols, but achieving no permanent re sults. He returned home at the end of 1272, the last of the western crusaders; and thus all the attempts of St. Louis and Charles of Anjou, of James of Aragon and Edward of England left Bibars still in possession of all his conquests.

Two projects of crusades were started before the final expul sion of the Latins from Syria. In 1274, at the Council of Lyons, Gregory X., who had been the companion of Edward in the Holy Land, preached the crusade to an assembly which contained envoys from the Mongol khan and Michael Palaeologus as well as from many western princes. All the princes of western Europe took the cross ; not only so, but Gregory was successful in uniting the Eastern and Western Churches for the moment, and in se curing for the new crusade the aid of the Palaeologi, now thoroughly alarmed by the plans of Charles of Anjou. Thus was a papal crusade begun, backed by an alliance with Constantinople, and thus were the plans of Charles of Anjou temporarily thwarted. But in 1276 Gregory X. died, and all his plans died with him ; there was to be no union of the monarchs of the West with the emperor of the East in a common crusade. Charles was able to resume his plans. In 1277 Mary of Antioch ceded to him her claims, and he was able to establish himself in Acre; in 1278 he took possession of the principality of Achaea. With these bases at his disposal he began to prepare a new crusade, to be directed primarily (like that of Henry VI. in 1197, and like his own projected crusade of 1270) against Constantinople. Once more his plans were fatally crossed : the Sicilian Vespers, followed by the coronation of Peter of Aragon as Sicilian king (1282), gave him troubles at home which occupied him for the rest of his days. This was the last serious attempt which was made in the West at a crusade on behalf of the dying kingdom of Jerusalem ; and its collapse was quickly followed by the final extinction of the kingdom. A precarious peace had reigned in the Holy Land since 1272, when Bibars had granted a truce of ten years; but the fall of the great power of Charles of Anjou set free Kala`un, the suc cessor of Bibars' son, to complete the work of the great sultan. In 1289 Kala`fln took Tripoli, and the county of Tripoli was ex tinguished; in 1290 he died while preparing to besiege Acre, which was captured after a brave defence by his son and successor Khalil in 1291. Thus the kingdom of Jerusalem came to an end. The Franks evacuated Syria altogether, leaving behind them only the ruins of their castles to bear witness, to this very day, of the crusades they had waged and the kingdom they had founded and lost.