The Fifth Crusade

THE FIFTH CRUSADE (1218-1221) The glow and glamour of the crusades disappear save for the pathetic sunset splendours of St. Louis, as Dandolo dies, and gal lant Villehardouin drops his pen. But before St. Louis sailed for Damietta there intervened the failure of one crusade, and the secular and diplomatic success of another. The fifth crusade is the last started in that pontificate of crusades—the pontificate of Inno cent III. It owed its origin to his feverish zeal for the recovery of Jerusalem, rather than to any pressing need in the Holy Land. Here reigned, during the 4o years of the loss of Jerusalem, an almost unbroken peace. Malik-al-Adil, the brother of Saladin, had by 1200 succeeded to his brother's possessions not only in Egypt but also in Syria, and he granted the Christians a series of truces (1198-1203, 1204-1o, 1211-17). While the Holy Land was thus at peace, crusaders were also being drawn elsewhere by the needs of the Latin empire of Constantinople, or the attractions of the Albigensian crusade (see ALBIGENSES). But Innocent could never consent to forget Jerusalem, as long as his right hand re tained its cunning. The pathos of the Children's crusade of 1212 only nerved him to fresh efforts. A shepherd boy named Stephen had appeared in France, and had induced thousands to follow his guidance : with his boyish army he rode on a wagon southward to Marseille, promising to lead his followers dry-shod through the seas. In Germany a child from Cologne, named Nicolas, gathered some 20,000 young crusaders by like promises, and led them into Italy. Stephen's army was kidnapped by slave-dealers and sold into Egypt; while Nicolas's expedition left nothing behind it but an after-echo in the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. But for Innocent these outbursts of the revivalist element, which always accompanied the crusades, had their moral: "the very children put us to shame," he wrote; "while we sleep they go forth gladly to conquer the Holy Land." In the fourth Lateran Council of 1215 Innocent found his opportunity to rekindle the flickering fires. Before this great gathering of all Christian Europe he proclaimed a crusade for the year 1217, and in common deliber ation it was resolved that a truce of God should reign for the next four years, and for the same period all trade with the Levant should cease. Here two things were attempted—neither, indeed, for the first time'—which 14th-century pamphleteers on the sub ject of the crusades unanimously advocate as the necessary con ditions of success ; there was to be peace in Europe and a com mercial war with Egypt. This statesmanlike beginning of a cru sade, preached, as no crusade had ever been preached before, in a general council of all Europe, presaged well for its success. In Germany (where Frederick II. himself took the cross in this same year) a large body of crusaders gathered together : in 1217 the south-east sent the duke of Austria and the king of Hungary to the Holy Land; while in 1218 an army from the north-west joined at Acre the forces of the previous year. Egypt had already been indicated by Innocent III. in 1215 as the goal of attack, and it was accordingly resolved to begin the crusade by the siege of Damietta, on the eastern delta of the Nile. The original leader of the cru sade was John of Brienne, king of Jerusalem (who had succeeded Amalric II., marrying Maria, the daughter of Amalric's wife Isa bella by her former husband, Conrad of Montferrat) ; but after 'A canon of the third Lateran Council (1179) forbade traffic with the Saracens in munitions of war; and this canon had been renewed by Innocent in the beginning of his pontificate.

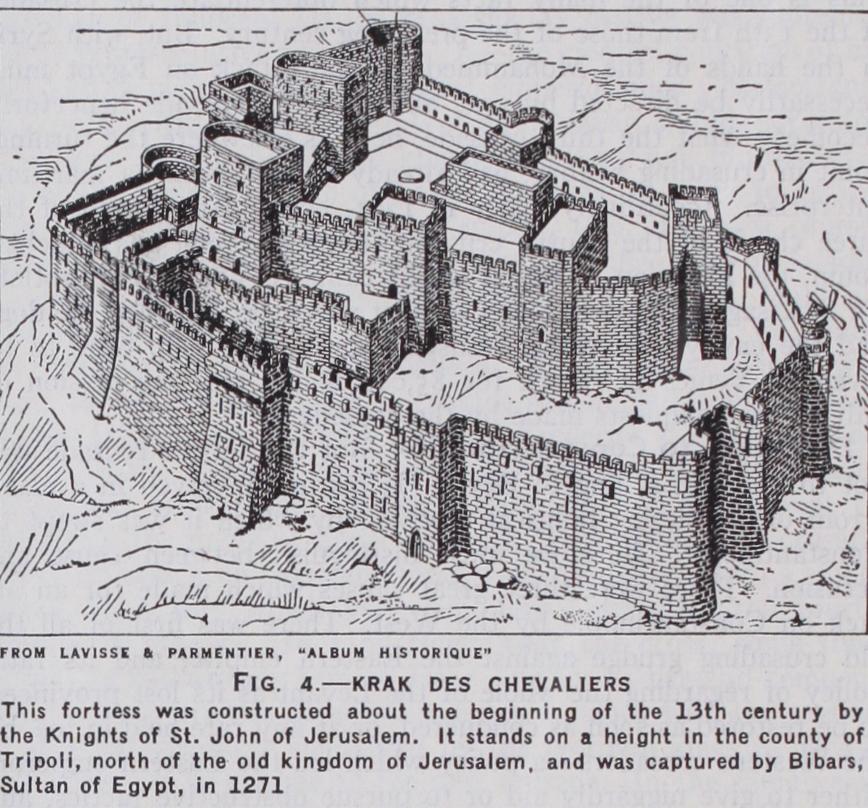

the end of 1218 the cardinal legate Pelagius, fortified by papal letters, claimed the command. In spite of dissensions between the cardinal and the king, and in spite of the offers of Malik-al-Kamil (who succeeded Malik-al-Adil at the end of 1218), the crusaders finally carried the siege to a successful conclusion by the end of 1219. The capture of Damietta was a considerable feat of arms, but nothing was done to clinch the advantage which had been won, and the whole of the year 1220 was spent by the crusaders in Damietta, partly in consolidating their immediate position, and partly in waiting for the arrival of Frederick II., who had promised to appear in 1221. In 1221 Hermann of Salza, the master of the Teutonic order, along with the duke of Bavaria, appeared in the camp before Damietta; and as it seemed useless to wait any longer for Frederick II., the cardinal, in spite of the opposition of King John, gave the signal for the march on Cairo'. The army reached a fortress (erected by the sultan in 1219, after wards, from 1221, the town of Mansura) , and encamped there at the end of July. Here the sultan reiterated terms which he had already offered several times before—the cession of most of the kingdom of Jerusalem, the surrender of the cross (captured by Saladin in 1187), and the restoration of all prisoners. King John urged the acceptance of these terms. The legate insisted on a large indemnity in addition : the negotiations failed, and the sultan pre pared for war. The crusaders were driven back towards Damietta; and at the end of Aug. 1221 Pelagius had to make a treaty with Malik-al-Kamil, by which he gained a free retreat and the sur render of the Holy Cross at the price of the restoration of Dam mietta. The treaty was to last for eight years, and could only be broken on the coming of a king or emperor to the East. In pursuance of its terms the crusaders evacuated Egypt, and the fifth crusade was at an end. It is difficult to decide whether to blame the legate or the emperor more for its failure. If Frederick had only come in person, a single month of his presence might have meant everything: if Pelagius had only listened to King John, the sultan was ready to concede practically everything which was at issue. Unhappily Frederick preferred to put his Sicilian house in order, and the legate preferred to listen to the Italians, who had their own commercial reasons for wishing to establish a strong position in Egypt, and to the Templars and Hospitallers, who did not feel satisfied by the terms offered by the sultan, because he wished to retain in his hands the two fortresses of Krak and Monreal.

'He had promised the pope, at his coronation in 1220, to begin his crusade in August 1221. But he declared himself exhausted by the expenses of his coronation ; and Honorius III. consented to defer his crusade until March 1 2 2 2. The letter of the pope informing Pelagius of this delay is dated June 20; it would probably reach his hands after his departure from Damietta ; and thus the cardinal gave the signal for the march, when, as he thought, the emperor's coming was imminent.

Ti3E SIXTH CRUSADE The sixth crusade succeeded as signally as the fifth had failed; but the circumstances under which it took place and the means by which it was conducted made its success still more disastrous than the failure of 1221. The last crusade had, after all, been under papal control : if Richard I. directed the third crusade, and the policy of the Hohenstaufen and the Venetians directed the fourth, it was a papal legate who steered the fifth to its fate. The crusade of Frederick II. in 1228-29 finds its analogy in the pro jected crusade of Henry VI. ; it is essentially lay. It is unique in the annals of the crusades. Alone of all crusades (though the fourth crusade offers some analogy) it was not blessed but cursed by the papacy : alone of all the crusades it was conducted without a single act of hostility against the Mohammedan. St. Louis, the true type of the religious crusader, once said that a layman ought only to argue with a blasphemer against Christian law by running his sword into the bowels of the blasphemer as far as it would go: Frederick II. talked amicably with all unbelievers, if one may trust Arabic accounts, and he achieved by mere negotiation the recovery of Jerusalem, for which men had vainly striven with the sword for the 4o years since 1187. It was in 1215 that the leader of this strange crusade had first taken the vow ; it was 12 years afterwards when he finally attempted to carry the vow into effec tive execution. Again and again he had excused himself to the pope, and been excused by the pope, because the exigencies of his policy in Germany or Sicily tied his hands. After the failure of the fifth crusade—for which these delays were in part responsible —Honorius III. had attempted to bind him more intimately to the Holy Land by arranging a marriage with Isabella, the daughter of John of Brienne, and the heiress of the kingdom of Jerusalem. In 1225 Frederick married Isabella, and immediately after the marriage he assumed the title of king in right of his wife, and exacted homage from the vassals of the kingdom'. It was thus as king of Jerusalem that Frederick began his crusade in the autumn of 1227. Scarcely, however, had he sailed from Brindisi when he fell sick of a fever which had been raging for some time among the ranks of his army, while they waited for the crossing. He sailed back to Otranto in order to recover his health, but the new pope, Gregory IX., launched in hot anger the bolt of excom munication, in the belief that Frederick was malingering once more. None the less the emperor sailed on his crusade in the summer of 1228, affording to astonished Europe the spectacle of an excommunicated crusader, and leaving his territories to be invaded by papal soldiers, whom Gregory IX. professed to regard as cru saders against a non-Christian king, and for whom he accordingly levied a tithe from the churches of Europe. The paradox of Frederick's crusade is indeed astonishing. Here was a crusader against whom a crusade was proclaimed in his own territories; and when he arrived in the Holy Land he found little obedience and many insults from all but his own immediate followers. Yet by adroit use of his powers of diplomacy and by playing upon the dissensions which raged between the descendants of Saladin's brother (Malik-al-Adil), he was able, without striking a blow, to conclude a treaty with the sultan of Egypt which gave him all that Richard I. had vainly attempted to secure by arduous fighting and patient negotiations. By the treaty of Feb. 18, 1229, which was to last for ten years, the sultan conceded to Frederick, in addition to the coast towns already in the possession of the Christians, Nazareth, Bethlehem and Jerusalem, with a strip of territory connecting Jerusalem with the port of Acre. As king of Jerusalem Frederick was now able to enter his capital : as one under excommunication, he had to see an interdict immediately fall on the city, and it was with his own hands—for no churchman could perform the office—that he had to take his crown from the altar of the church of the Sepulchre, and crown himself king of his new kingdom. He stayed in the Holy Land little more than a month after his coronation ; and leaving in May he soon over 'John of Brienne had only ruled in right of his wife, Mary. On her death (1212) John might be regarded as only ruling "by the courtesy of the kingdom" until her daughter, Isabella, was married, when the husband would succeed. That, at any rate, was the view Frederick II. took.

came the papal armies in Italy, and secured absolution from Gregory IX. (Aug. 1229). By his treaty with the sultan he had secured for Christianity the last 15 years of its possession of Jerusalem (1229-44) : no man after Frederick II., until our own day, ever recovered the holy places for the religion which holds them most holy. Yet the Church might ask, with some justice, whether the means he had used were excused by the end which he had attained. After all, there was nothing of the holy war about the sixth crusade : there was simply huckstering, as in an Eastern bazaar, between a free-thinking, semi-oriental king of Sicily and an Egyptian sultan. It was indeed in the spirit of a king of Sicily, and not in the spirit—though it was in the role—of a king of Jerusalem, that Frederick had acted. It was from his Sicilian predecessors, who had made trade treaties with Egypt, that he had learned to make even the crusade a matter of treaty. The Norman line of Sicilian kings might be extinct ; their policy lived after them in their Hohenstaufen successors, and that policy, as it had helped to divert the fourth crusade to the old Norman objective of Constantinople, helped still more to give the sixth crusade its secular, diplomatic, non-religious aspect.

Forty years of struggle terminated in the possession of Jeru salem for i 5 years. During those 15 years the kingdom of Jerusalem was agitated by a struggle between the native bar ons, championing the principle that sovereignty resided in the collective baronage, and taking their stand on the assizes, and Frederick II., claiming sovereignty for himself, and opposing to the assizes the feudal law of Sicily. It is a struggle between the king and the haute tour: it is a struggle between the aristo cratic feudalism of the Franks and the monarchical feudalism of the Normans. Already in Cyprus, in the summer of 1228, Fred erick II. had insisted on the right of wardship which he enjoyed as overlord of the island', and he had appointed a commission of five barons to exercise his rights. In 1229 this commission was overthrown by John of Ibelin, lord of Beirut, against whom it had taken proceedings. John of Beirut, like many of the Cypriot barons, was also a baron of the kingdom of Jerusalem; and re sistance in the one kingdom could only produce difficulties in the other. Difficulties quickly arose when Frederick, in 1231, sent Marshal Richard to Syria as his legate. This in itself was a serious matter; according to the assizes, the barons maintained, the king must either personally reside in the kingdom, or, in the event of his absence, be represented by a regency. The position became more difficult, when the legate took steps against John of Beirut without any authorization from the high court. A gild was formed at Acre—the gild of St. Adrian—which, if nominally religious in its origin, soon came to represent the political opposition to Fred erick, as was significantly proved by its reception of the rebellious John of Beirut as a member (1232). The opposition was success ful: by 1233 Frederick had lost all hold on Cyprus, and only re tained Tyre in his own kingdom of Jerusalem. In 1236 he had to promise to recognize fully the laws of the kingdom : and when, in 1239, he was again excommunicated by Gregory IX., and a new quarrel of papacy and empire began, he soon lost the last vestiges of his power. Till 1243 the party of Frederick had been success ful in retaining Tyre, and the baronial demand for a regency had remained without effect ; but in that year the opposition, headed by the great family of Ibelin, succeeded, under cover of asserting the rights of Alice of Cyprus to the regency, in securing possession of Tyre, and the kingdom of Jerusalem thus fell back into the power of the baronage. The very next year (1244) Jerusalem was finally lost. Its loss was the natural corollary of these dis sensions. The treaty of Frederick with Malik-al-Kamil (d. 1238) had now expired, and new succours and new measures had become necessary for the Holy Land. Theobald of Champagne had taken the cross as early as 123o, and in 1239 he sailed to Acre in spite of the express prohibition of the pope, who, having quarrelled with Frederick II., was eager to divert any succour from Jerusalem itself, so long as Jerusalem belonged to his enemy. Theobald was followed (124o-41) by Richard of Cornwall, the brother of Henry III., who, like his predecessor, had to sail in 'Amalric I. of Cyprus had done homage to Henry VI. from whom he had received the title of king (1195).

the teeth of papal prohibitions; but neither of the two achieved any permanent result, except the fortification of Ascalon. It was, however, by their own folly that the Franks lost Jerusalem in 1244. They consented to ally themselves with the ruler of Da mascus against the sultan of Egypt; but in the battle of Gaza they were deserted by their allies and heavily defeated by Bibars, the Egyption general and future Mameluke sultan of Egypt. Jerusalem, which had already been plundered and destroyed earlier in the year by Chorasmians (Khwarizmians), was the prize of victory, and Ascalon also fell in 1247.