The Worlds Cotton Power Looms

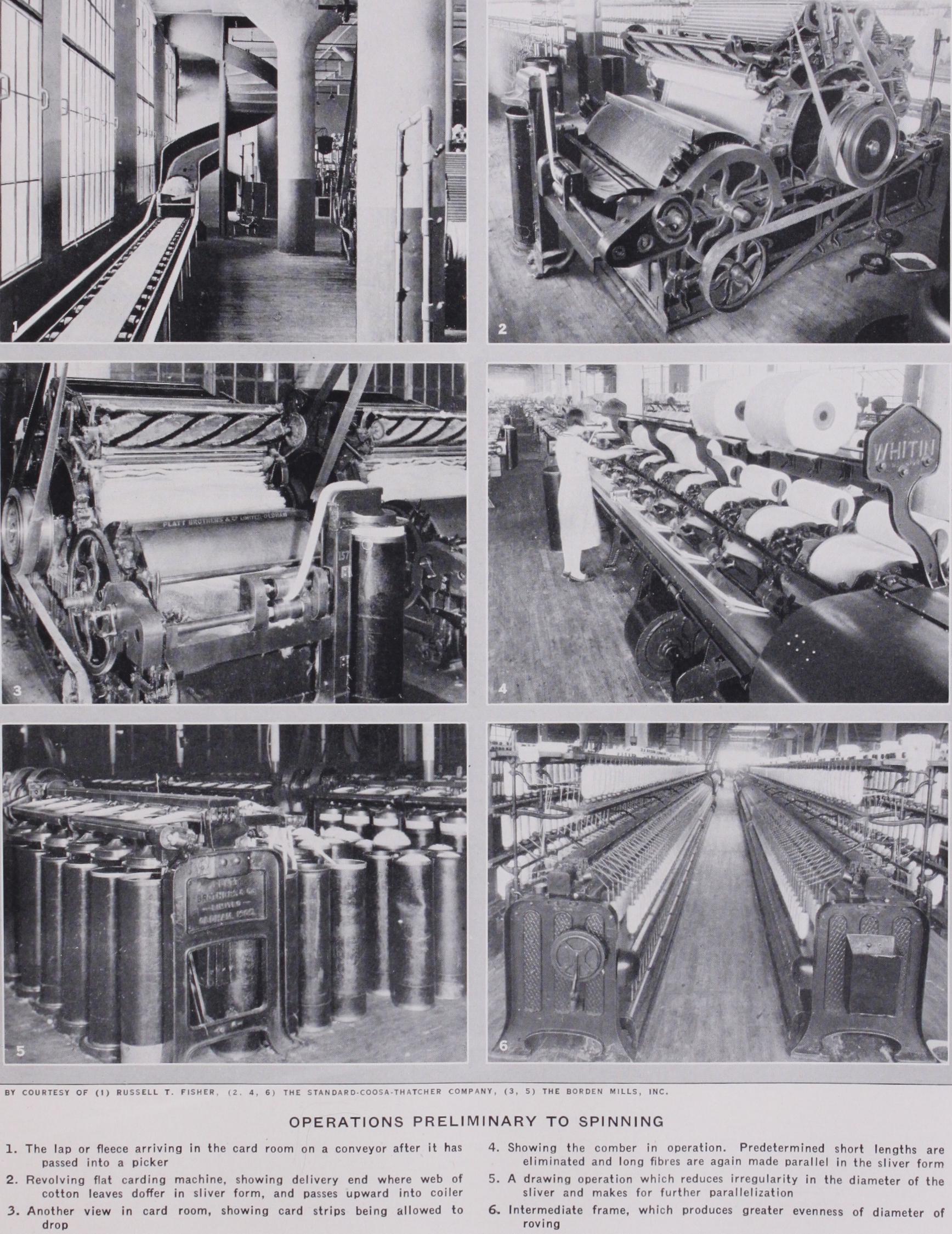

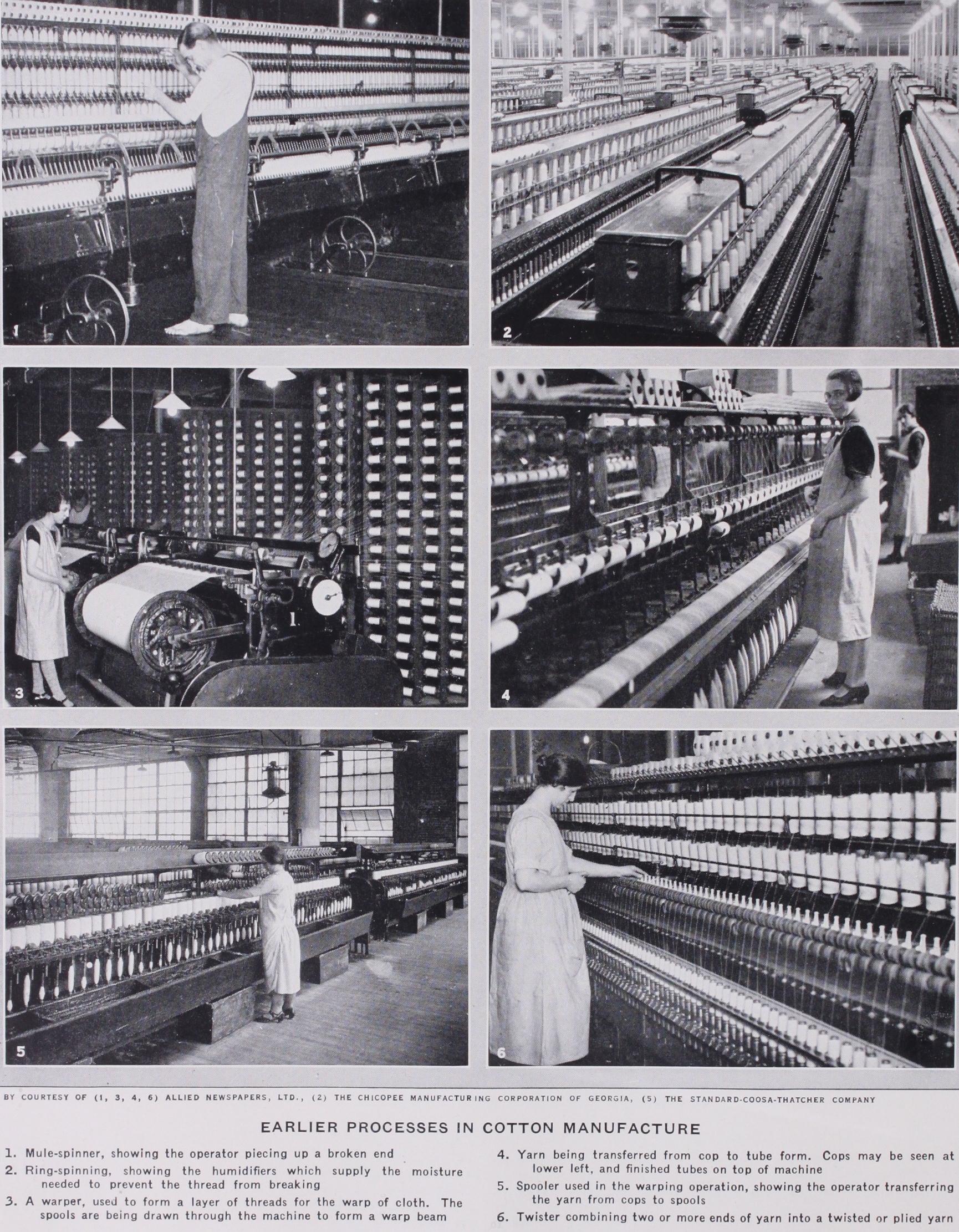

THE WORLD'S COTTON POWER LOOMS Statistics of the power looms of the world are neither so com plete nor so conclusive as those for spindles. They are incomplete because, on the weaving side of the world textile trade, there is no organization responsible for the collection of statistics such as the International Federation of Master Cotton Spinners on the spin ning side. They are inconclusive because of the numberless types of looms which exist, each type representing a different weaving capacity, or a weaving capacity in a specialized line of goods. At the one end, in very many countries—particularly in the East— some looms worked by power show little advance upon the hand loom. At the other the most modern type of power loom, with its automatic action and the slight demand which it makes upon the skill and intelligence of the operative, is a unit of potential cloth output quite different from the machines, long installed and but partially adapted to cope with recent changes in the quality and types of cloth demanded, which are found on a large scale in Lancashire. It is important, therefore, to treat all such statistics with caution. Two looms in one country may represent the same potential productive output as one loom in another.

According to the latest information published in Skinner's Tex tile Directory the distribution of looms between the nations of the world was as follows :— In the world as a whole there are two mule spindles to each three ring spindle, but the proportions vary widely from country to country. In Great Britain, where the finest goods are made and where two-thirds of the total mules in the world are found, there are more than three mules to each ring spindle. In most other countries, particularly in the East and in the United States, the mule spindles are overwhelmingly outnumbered, a sure proof of the low average counts spun there, and if the counts of yarn are low, the fabric is not so closely woven.

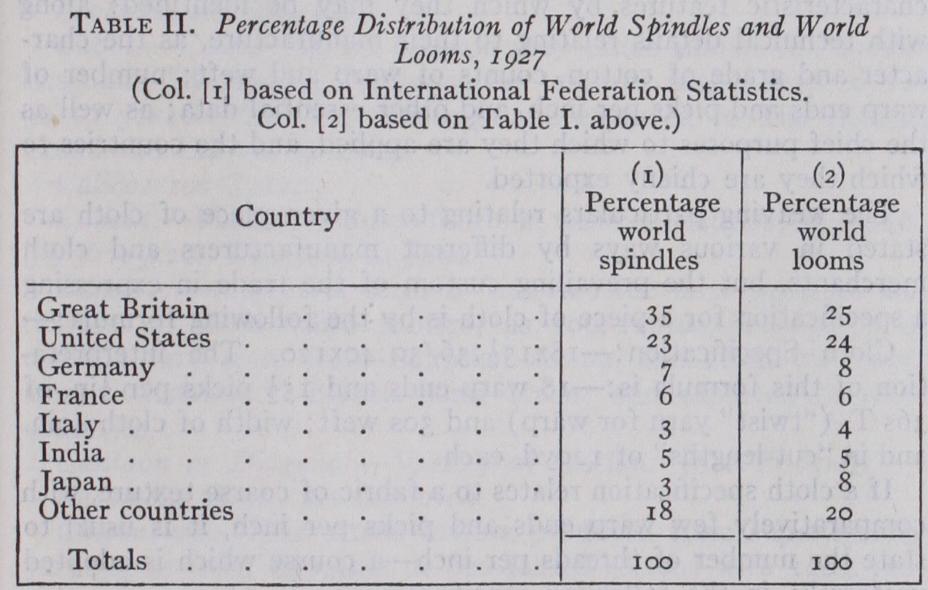

Similar conclusions are reached by comparing the numbers of spindles consuming the different types of cotton. Egyptian cotton is not only the finest obtainable, but it is almost indispensable for the production of the highest quality yarn. The figures published by the International Federation of Master Cotton Spinners show that only about one in every six spindles is engaged in spinning Egyptian and that nearly 7o% of the spindles spinning Egyptian cotton are to be found in Great Britain, though there are indica tions that other countries are beginning to increase their output of the finest yarns. The position in this respect at the beginning of 1927 was as follows:— Great Britain and the United States of America have about equal numbers with more than three times as many looms as their nearest competitors, Germany and Japan. France, India and Italy are next in order of size. Great Britain and the United States have between them about half the power looms in the world, whilst the seven countries specially named in the table have some 8o% of the world total.

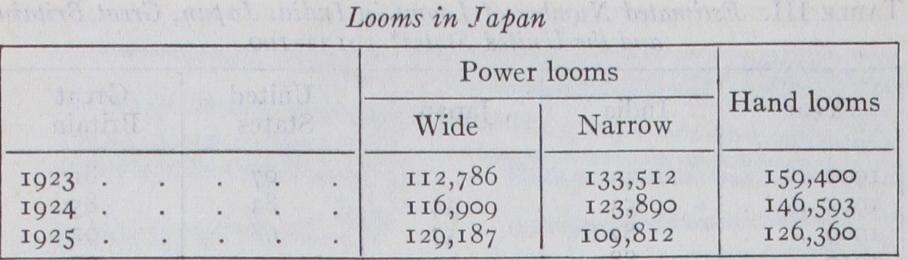

A comparison of this distribution with that of world spindles produces interesting and suggestive conclusions. In the table be low the statistics of the International Federation of Master Cot ton Spinners are used for the "Spindle" column and the percen age distribution of looms based upon the figures already quoted. The outstanding features of Table II. are the abnormally high percentage of spindles to be found in Great Britain and the remarkably high percentage of looms attributed to Japan. The spindle capacity of Great Britain is much more significant in world affairs than her loom capacity. It appears that the devel opment of the cotton industry in Great Britain has taken a form in which the spinning section is very much dependent for normal prosperity upon the production of large quantities of yarn which will be absorbed not by the home looms, but either by the export yarn trade or by the other textile industries in the country—wool, hosiery, lace—which use large quantities of cotton yarn for mixing with their own special fibres. The abnormal posi tion of Japan is not easy to explain. Many of the looms in that country—in 1924 more than 5o%—were "narrow" looms and therefore of fairly low productive capacity. The number of hand looms in that country has decreased appreciably in recent times and the spindles existing have been working double time over long periods so that the output of yarn has been much greater than the spindleage would suggest. But these facts provide only a partial explanation of a rather perplexing discrepancy which could prob ably be fully elucidated only by a detailed, technical census and study of the mechanical equipment of the industry and the normal methods of industrial organization.

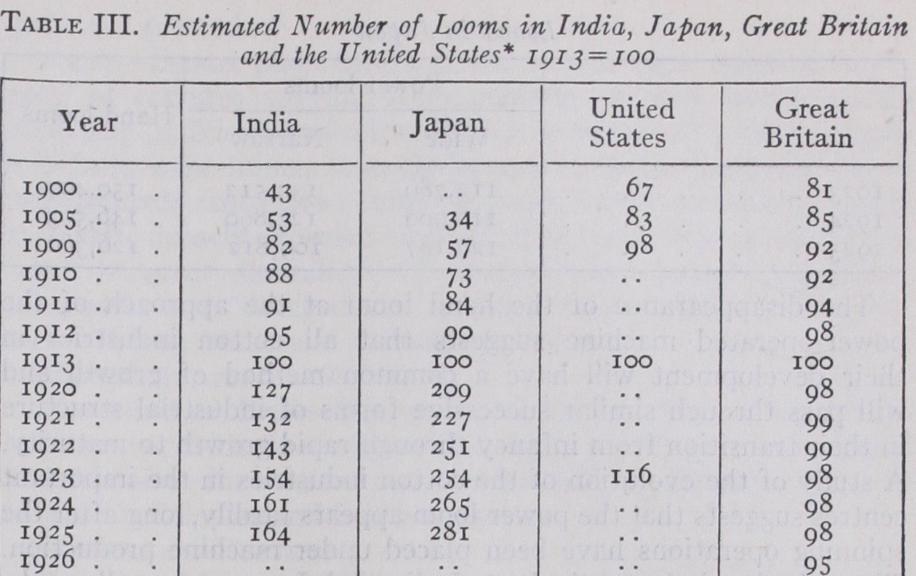

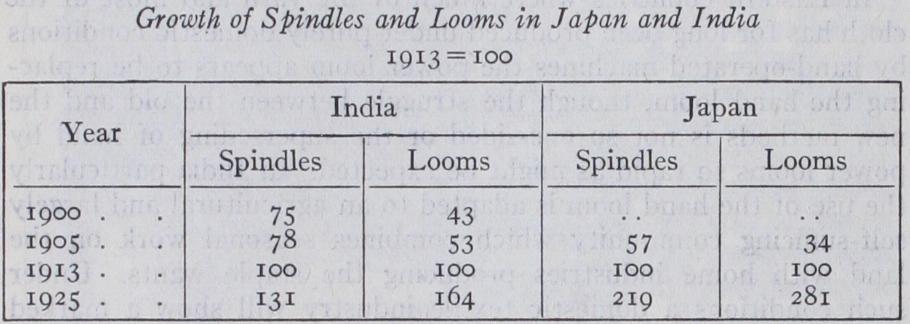

If the task of estimating the existing distribution of looms in the world is difficult, that of calculating the growth of loom power in any country during a period of years is doubly hazardous, since the type of loom employed may have considerably changed, thus invalidating the accuracy of any statistics. It is almost certain, to take one example, that those countries in which the cotton in dustry has developed rapidly in the last r o-20 years will have textile machinery rather more modern and therefore rather more scientific and efficient than those countries in which, during this period, size has remained comparatively constant. On the other hand it must not be overlooked that the increased amount of textile machinery in Japan or India contains many second-hand spindles and looms shipped from countries where the cotton industry developed comparatively early. In Table III. is shown the percentage growth of looms in Great Britain, India, Japan and the United States. The figures for Japan are based upon a sample only of the total industry, but as the sample is one of so% it is probably adequate. The most marked growth is that of Japan. Between 1905 and 1913 the number of looms in creased almost threef old and there was a similar increase between 1913 and 1925 despite the damage caused by the earthquake in 1923. In India the increase is less marked but is yet important enough to disclose the reason for the increased competition pro vided by this country since the World War. The looms in the United States are increasing slowly where the progress is confined almost wholly to the industry of the Southern States, whilst in Great Britain the comparative maturity of the industry before the war is revealed by the slight increase from r 90o to 1913 and the depression since r920 by an actual decrease in the number of looms.

*Based on figures from:— India: Bombay Cotton Mill Owners' Year Book.

Japan: Japan Cotton Spinners' Association, Osaka.

United States: Statistical Abstract of the United States Bureau of Census.

Great Britain: Worrall's Cotton Trade Directory.

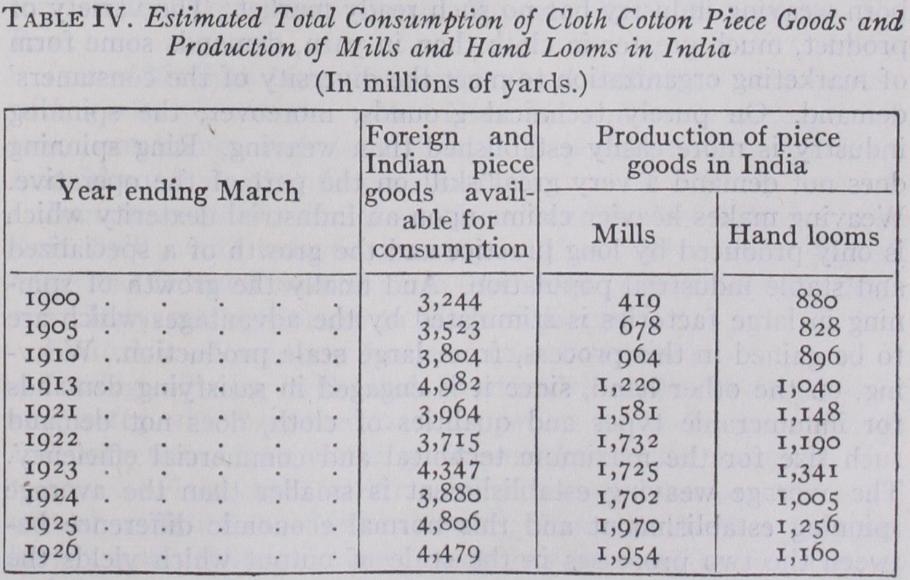

In Eastern countries where much of the yarn and most of the cloth has for long been produced under purely domestic conditions by hand-operated machines the power loom appears to be replac ing the hand loom, though the struggle between the old and the new methods is not so one-sided or the superseding of hand by power looms so rapid as might be expected. In India particularly the use of the hand loom is adapted to an agricultural and largely self-sufficing community which combines seasonal work on the land with home industries producing the staple wants. Under such conditions a domestic textile industry will show a marked capacity to resist the competition of machine-made products and a habit of recuperating whenever the machine goods become too high in price. During the World War, when outside supplies of cloth were scarce in India, the production of hand looms actually increased and the abnormally high prices which ruled for cotton goods between r 92 r and 1925 further stimulated home production. But the inevitable superiority of machine-made goods in the long run, both on the score of price and quality, will ultimately bring a larger proportion of total consumption within the domain of the machine. This is going on in both India and Japan, though in the latter country the statistics are too fragmentary completely to justify the general opinion of those who are in closest contact with economic change and who assert that such a movement is occurring. In India, however, hand loom production of cloth now represents a smaller proportion of total consumption than for merly. Table IV., which reveals this, is taken from the Report of the Indian Tariff Board, 1927.

The only other information of the same kind which can be relied upon is that for Japan in the years 1923-24-25, which shows, however, that even between these three years there was a con siderable decrease in hand looms.

The disappearance of the hand loom at the approach of the power-operated machine suggests that all cotton industries in their development will have a common method of growth and will pass through similar successive forms of industrial structure in their transition from infancy through rapid growth to maturity. A study of the evolution of the cotton industries in the important centres suggests that the power loom appears tardily, long after the spinning operations have been placed under machine production. The spinning industry in both India and Japan was well estab lished bef ore cloth began to be produced on any large scale on power looms, and the history in the 20th century is that of the number of power looms increasing more rapidly than that of spindles in order to produce a normal balance. Thus, in India and Japan, looms increased much more rapidly than spindles from 1900 to 1925.

Once something approximating to an equilibrium between spin dles and looms has been established, as is the case in Great Britain and the United States, then this marked divergence in the rate of growth will tend to disappear, but apparently it is normal for a growing cotton industry to concentrate early upon the production of mill-made yarn and to turn to factory-made cloth much later in its development.

The reasons for the retarded appearance of the power loom are not difficult to discover. A spinning industry from its inception finds an immediate and ready market for its yarn among the owners of hand looms who previously will have provided them selves with yarn laboriously spun on the old spinning wheel. When both the yarn and cloth are produced on hand-operated machines there is usually a shortage of yarn, since the spinning jenny makes yarn much less quickly than it can be woven into cloth on the hand loom. That was the experience even in England in the early stages of development of the cotton industry. A new born weaving industry has no such ready market. The variety of product, much greater in cloth than in yarn, demands some form of marketing organization to meet the diversity of the consumers' demand. On purely technical grounds, moreover, the spinning industry is more easily established than weaving. Ring spinning does not demand a very great skill on the part of the operative. Weaving makes heavier claims upon an industrial dexterity which is only produced by long practice and the growth of a specialized and stable industrial population. And finally the growth of spin ning in large factories is stimulated by the advantages which are to be gained in this process, from large scale production. Weav ing, on the other hand, since it is engaged in satisfying demands for innumerable types and qualities of cloth, does not demand such size for the maximum technical and commercial efficiency. The average weaving establishment is smaller than the average spinning establishment and this normal economic difference be tween the two processes in the scale of output which yields the best results may well have operated at the early stages of indus trial development to check the appearance of a power-operated weaving industry at all.