The Worlds Cotton Supplies

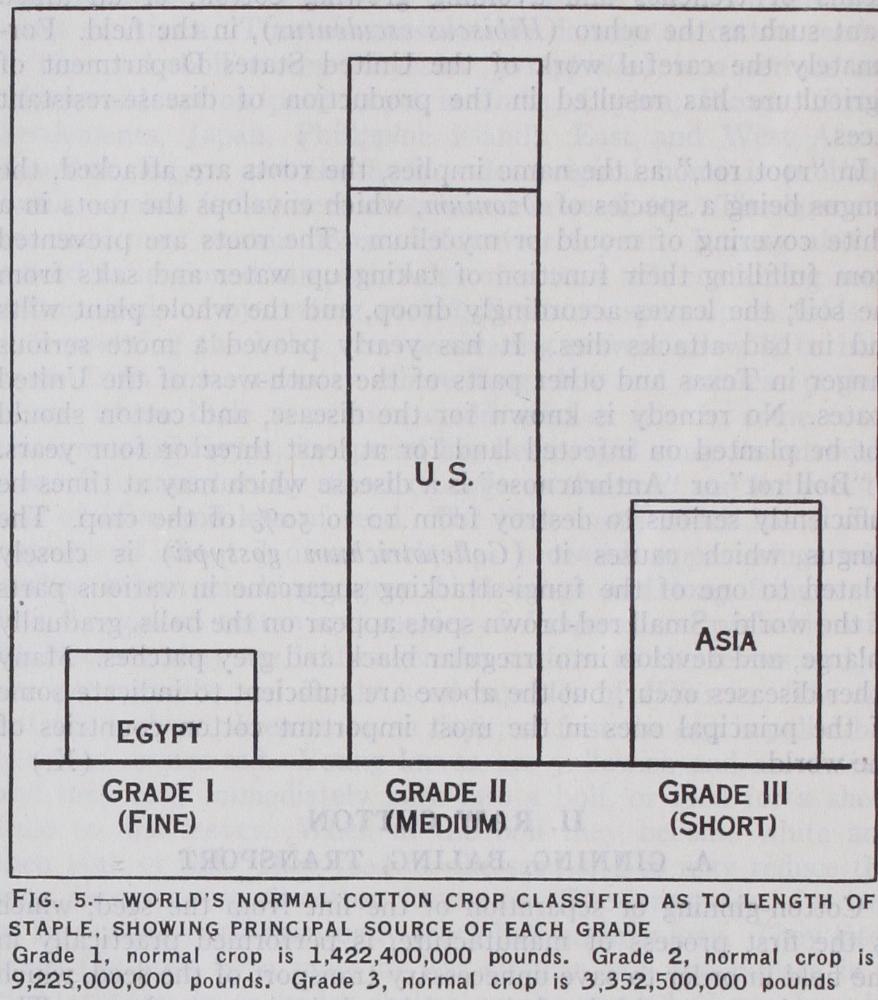

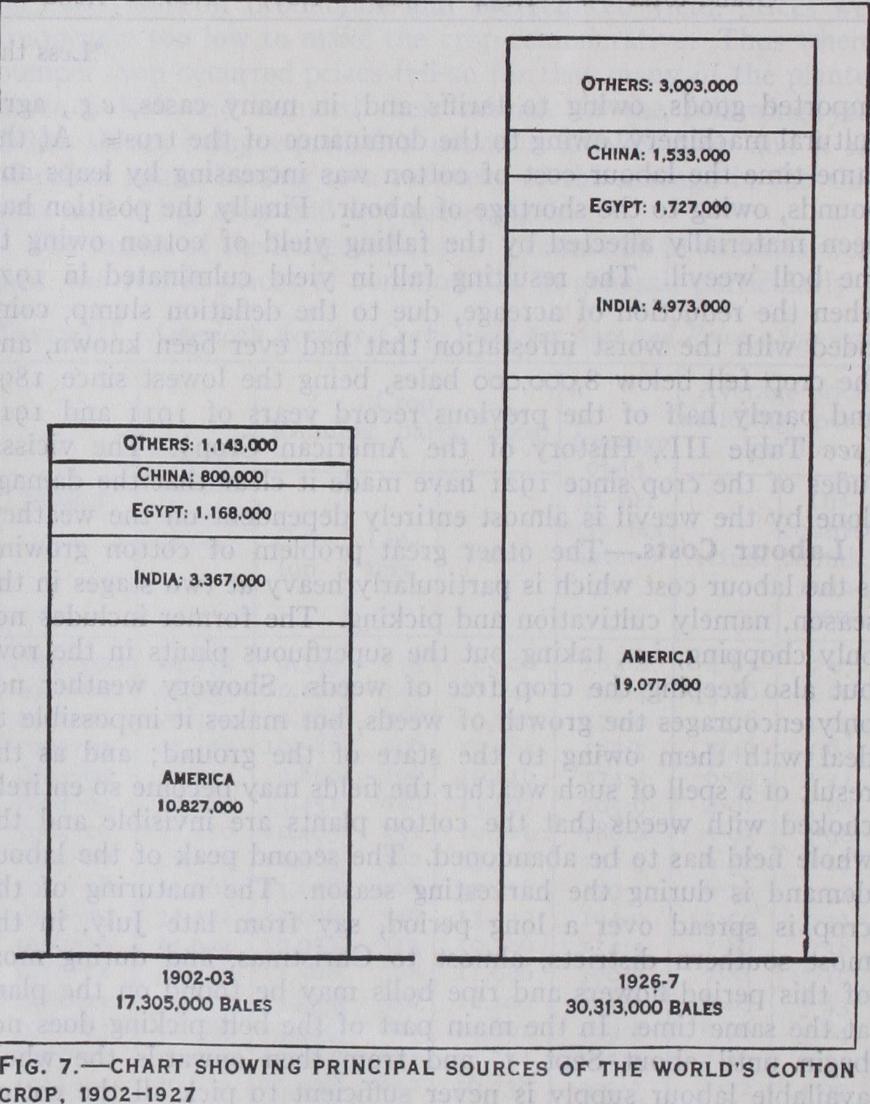

THE WORLD'S COTTON SUPPLIES The world's cotton supplies are so widely distributed and vary so greatly in quality and value that some principle of classifica tion is necessary to obtain a comprehensive and intelligible view of the supplies as a whole. From a manufacturing point of view the most convenient classification is according to the length of staple. On this principle all the world's cottons may be roughly classified into three main grades which may be called fine, medium and short staple ; and in Table I. the world's principal crops and many of the smaller ones are divided into these three grades with an indication of their staple length, the counts to which they will spin and their relative commercial values. It must be kept in view, however, that this classification is very uncertain and changes frequently. Some of the crops included in Grade I., e.g., Uganda, are very little better than the best varieties of Grade II. Again the division of certain crops between different grades is rather arbitrary and varies from season to season; e.g., the pro portion of the Brazilian crop which might be regarded as falling into Grade I., or the division of the Russian and Chinese crops between Grades II. and III. The table also indicates the propor tion of each grade grown in the British empire.

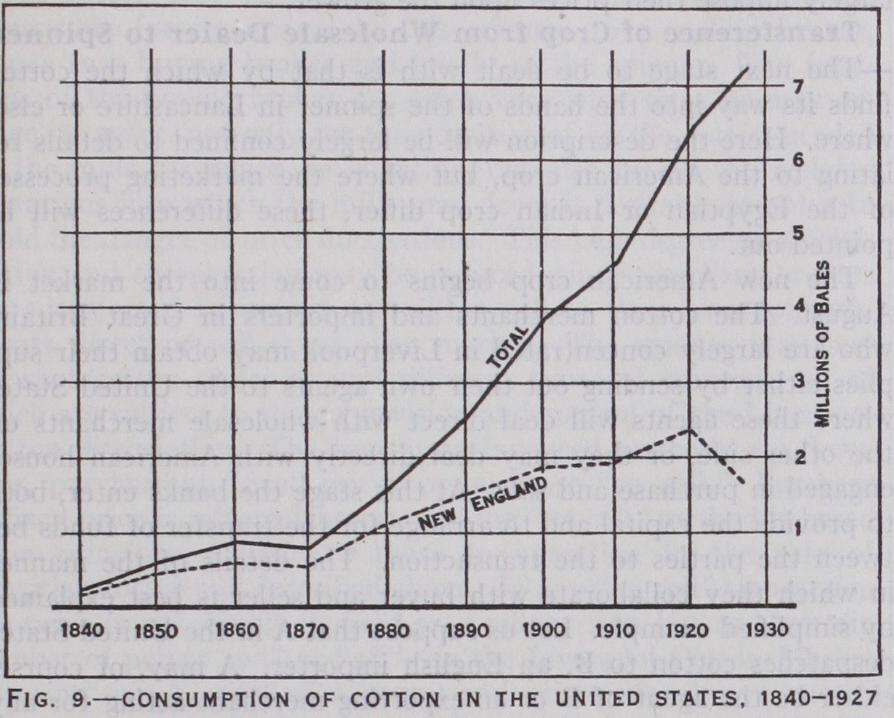

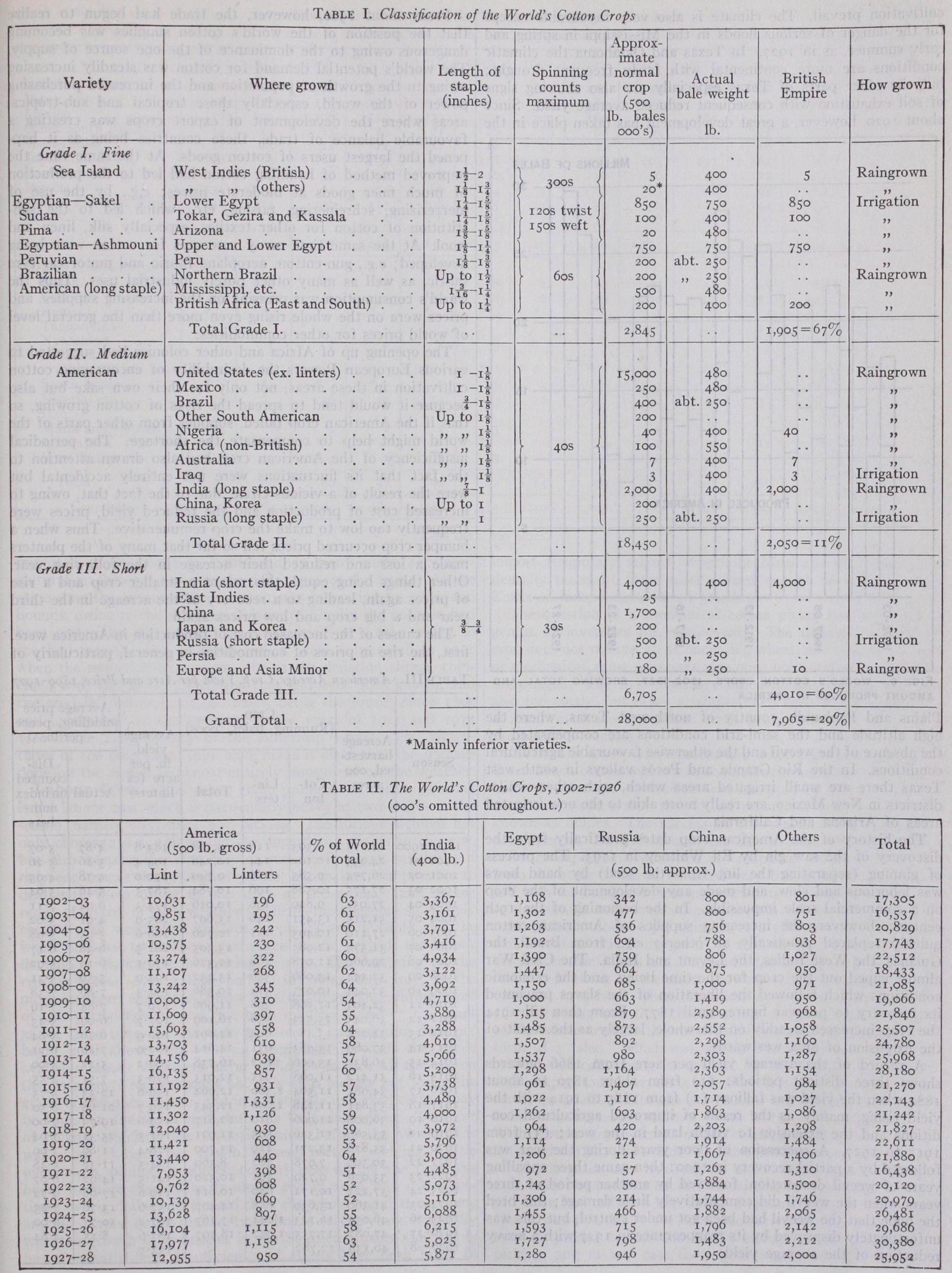

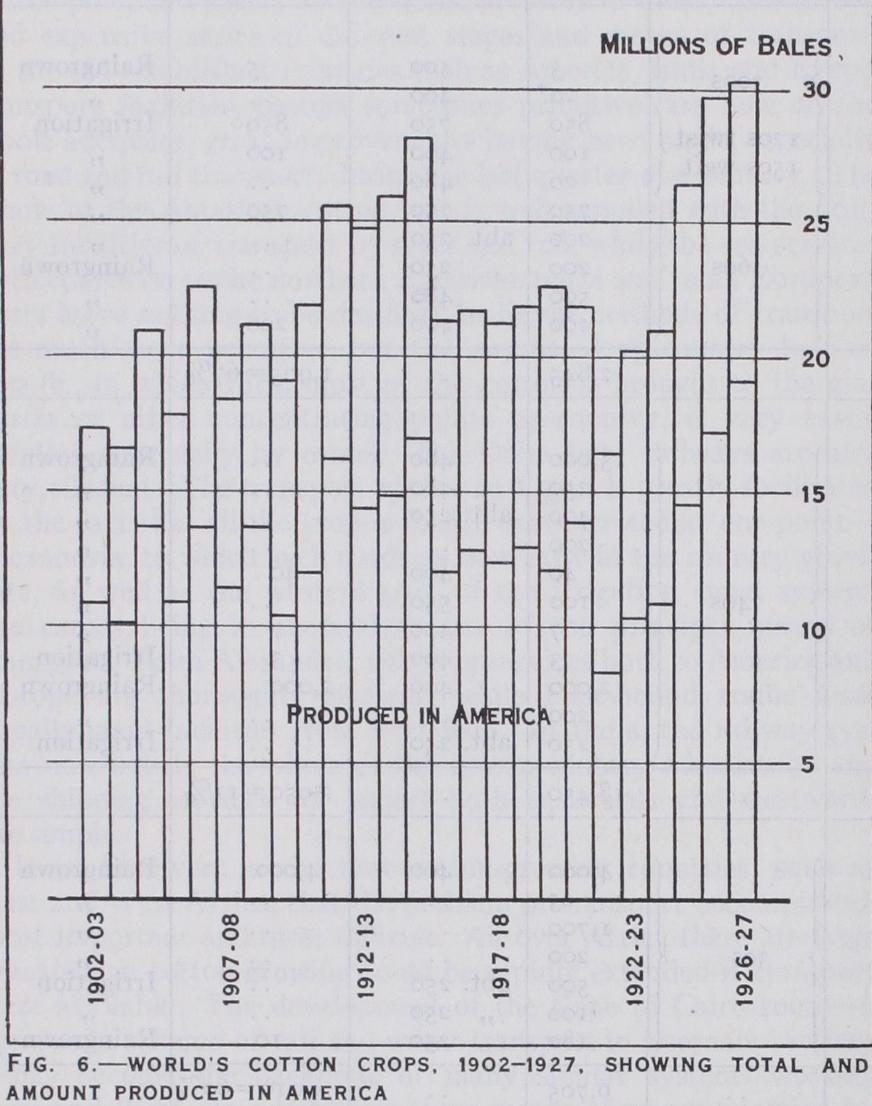

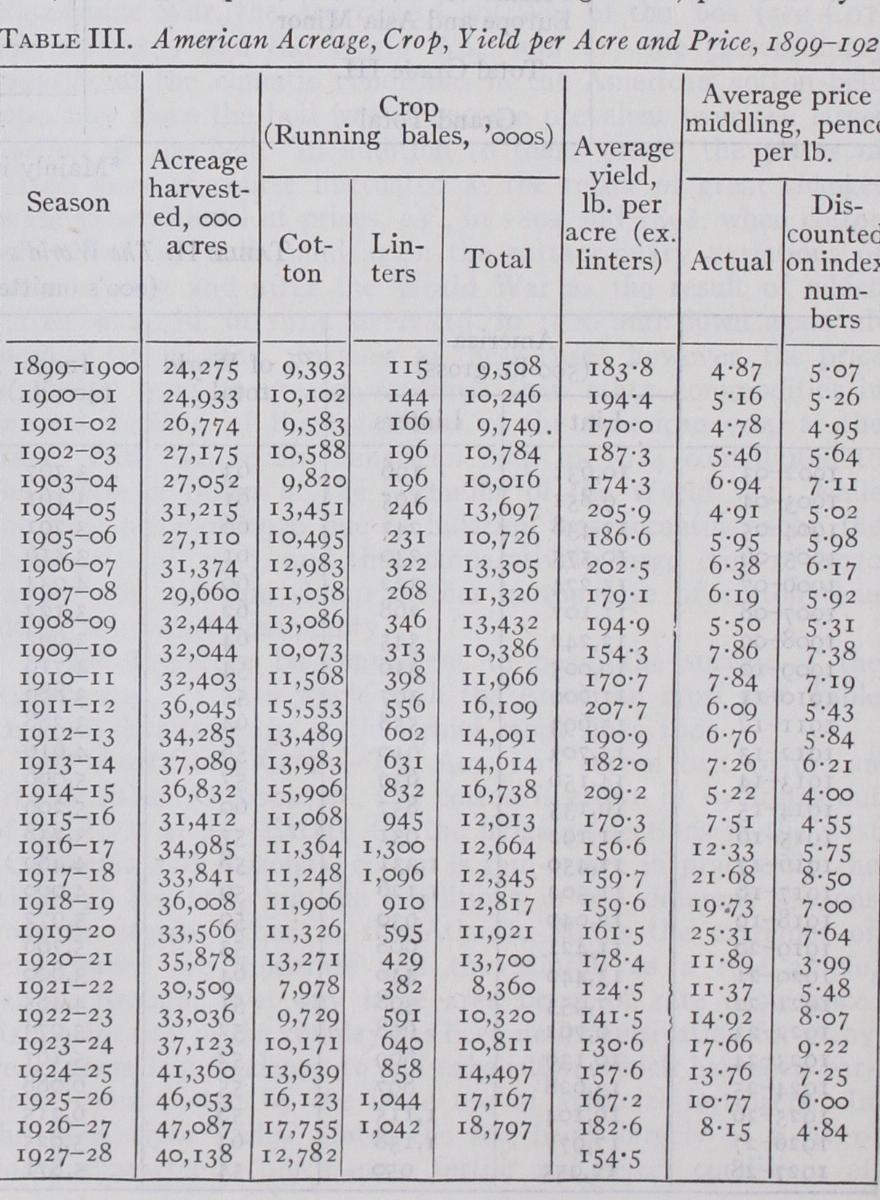

The outstanding feature of the cotton industry which is the source of most of its difficulties is the extraordinary variation of the world's supplies from one season to another, producing very severe fluctuations in prices, and as the cost of the raw material forms a very Iarge proportion of the cost of production of the finished article, and the consumption of cotton goods depends very largely on their price, these fluctuations are a serious handi cap to the development of a steady trade. The main cause of this irregularity of supplies lies in the fact that for nearly a century the American crop has dominated the world's supply, being sometimes as much as two-thirds of the whole, and the supply of American cotton has been extraordinarily variable. The main causes of this variation have been (1) wars, e.g., the Napoleonic War, the American Civil War of the '6os (see COT TON FAMINE) and the World War, and (2) the extraordinary vagaries of the climatic conditions in the American cotton belt, especially since the boll weevil became prevalent over the larger portion of the belt. In addition to these causes the prices of cotton have of course fluctuated as the result of great changes in the general level of prices, e.g., in 1894 and 1898, when cotton was below 3d. a lb., and again the extraordinary variations of prices during and after the World War as the result of which cotton was 43d. in 1914, over 31d. in 1920 and down again al most to 6d. in 1921. In most of these cases, however, the price of cotton went to greater extremes than other commodities in general, because of the conditions of the American crop at the time. Thus the record American crop in 1914 contributed to the slump in prices at the beginning of the World War, while the high price of 1920 due to inflation was accentuated by the short crop of 1919, and comparatively large crop of 1920 carried the deflation slump farther in the case of cotton than almost any other commodity.

It will therefore be convenient to begin the survey of the world's supplies as a whole with the American crop, but Table II. gives details of the world's chief crops since 1902.

The

American American cotton belt covers an area of about 7oo,000sq.m., and cotton is grown in 19 States out of the total of 48. Except for the irrigated sections in the west (California and Arizona), cotton is rain-grown in practically the whole of the belt, but the conditions in the different sections vary in degree. Thus in the Atlantic States the extremes of temperature are moderate and the rainfall as a rule ample, serious drought over any large area being of rare occurrence. As a great deal of the country has been under cultivation for many years there is a tendency to soil exhaustion, which has been par tially counteracted by the large use of artificial fertilizers. In the Mississippi Valley States the soil being largely of a river borne character is much more fertile and better conditions of cultivation prevail. The climate is also very favourable except for the danger of serious floods in the Mississippi in spring and early summer, as in 1927. In Texas and Oklahoma the climatic conditions are more continental with fairly frequent drought ; but the older parts of Texas especially are also showing signs of soil exhaustion with consequent reduced average yield. Since about 192o, however, a great development has taken place in the Plains and Panhandle country of north-west Texas, where the high altitude and the semi-arid conditions are compensated by the absence of the weevil and the otherwise favourable agricultural conditions. In the Rio Grande and Pecos valleys in south-west Texas there are small irrigated areas which, with other similar districts in New Mexico, are really more akin to the new irrigated areas of Arizona and California.

The history of the American crop dates practically from the discovery of the saw gin by Eli Whitney in 1793. The process of ginning (separating the lint from the seed) by hand bows was laborious and slow, and made any development of the crop on a commercial scale impossible. In the beginning of the i 9th century, however, the increasing supplies of American cotton quickly replaced practically all others; e.g., from Brazil, the Guianas, the West Indies, the Levant and India. The Civil War almost wiped out the crop for the time being, and the economic conditions which followed the liberation of the slaves prevented its recovery to pre-war figures until 1877. From then till 1914 the crop increased steadily on the whole, largely as the result of the extension of area westwards.

A record of the average yield per acre from 1866 onwards shows three distinct periods: (I) from about 18 7o to about 1884 when the yield was falling; (2) from 1885 to 1914 with the yield rising, mainly as the result of improved agricultural con ditions and the extension to virgin land in the west; (3) from 1915 to 1927. A succession of poor years during the war was followed by a partial recovery in 1920; then came three appalling years of weevil destruction, followed by another period of three years when the weevil did comparatively little damage; this bred the hope that the weevil had been got under control, but this was unfortunately disproved by its reappearance in 1927 with a heavy reduction of the average yield.

From about 'goo, however, the trade had begun to realize that the position of the world's cotton supplies was becoming dangerous owing to the dominance of the one source of supply. The world's potential demand for cotton was steadily increasing owing to the growth of population and the increased purchasing power of the world, especially those tropical and sub-tropical areas where the development of export crops was creating a favourable balance of trade, these countries being as it hap pened the largest users of cotton goods. At the same time the improved method of handling cotton had led to the production of much finer goods at moderate prices; e.g., by the use of mercerizing, schreinering, raising, etc., which led to the sub stitution of cotton for other textiles, especially silk, linen and wool. At the same time many new uses for cotton were being developed; e.g., gun-cotton, aeroplane fabric and motor car tyre fabric, as well as many other purely industrial uses. Thus the world's consumption was pressing on the increasing supplies, and prices were on the whole rising even more than the general level of world prices for other commodities.

The opening up of Africa and other colonies had suggested to various European Powers the desirability of encouraging cotton cultivation in these areas, not only for their own sake but also because it would tend to spread the risks of cotton growing, so that if the American crop failed, supplies from other parts of the world might help to compensate the shortage. The periodical insufficiency of the American crop had also drawn attention to the fact that its fluctuations were not entirely accidental but were the result of a vicious circle, due to the fact that, owing to increased cost of production and the reduced yield, prices were frequently too low to make the crop remunerative. Thus when a bumper crop occurred prices fell so far that many of the planters made a loss and reduced their acreage in the following year. Other things being equal, this meant a smaller crop and a rise of prices again, leading to a recovery of the acreage in the third year and a big crop and low prices again.

The causes of the increased cost of production in America were, first, the rise in prices of commodities in general, particularly of imported goods, owing to tariffs and, in many cases, e.g., agri cultural machinery, owing to the dominance of the trusts. At the same time the labour cost of cotton was increasing by leaps and bounds, owing to the shortage of labour. Finally the position had been materially affected by the falling yield of cotton owing to the boll weevil. The resulting fall in yield culminated in 1921 when the reduction of acreage, due to the deflation slump, coin cided with the worst infestation that had ever been known, and the crop fell below 8,000,000 bales, being the lowest since 1895 and barely half of the previous record years of 1911 and 1914 (see Table III., History of the American Crop). The vicissi tudes of the crop since 1921 have made it clear that the damage done by the weevil is almost entirely dependent on the weather.

Labour Costs.—The other great problem of cotton growing is the labour cost which is particularly heavy at two stages in the season, namely cultivation and picking. The former includes not only chopping, i.e., taking out the superfluous plants in the row, but also keeping the crop free of weeds. Showery weather not only encourages the growth of weeds, but makes it impossible to deal with them owing to the state of the ground ; and as the result of a spell of such weather the fields may become so entirely choked with weeds that the cotton plants are invisible and the whole field has to be abandoned. The second peak of the labour demand is during the harvesting season. The maturing of the crop is spread over a long period, say from late July, in the most southern districts, almost to Christmas, and during most of this period flowers and ripe bolls may be found on the plant at the same time. In the main part of the belt picking does not begin until about Sept. 1, and from then onwards the whole available labour supply is never sufficient to pick all the cotton that is open. Frequent rains not only stop picking but lower the grade of the open cotton, and in a wet year unpicked cotton may be found in the fields right into the following spring. The cost of picking which in the Atlantic States before the World War was about 75 cents per zoo lb. of seed cotton (yielding a little over 3o lb. of lint or ginned cotton) rose during the post war boom to more than twice as much, and in 1926 was still some times over a dollar. In the old days the whole population, young and old, turned out at picking time, but in recent years, especially with the growth of industries in the Southern towns, the supply has frequently been insufficient and efforts have been made to import temporary labour, especially Mexicans in Texas. Inci dentally many of these have earned enough to settle down in Texas as independent cotton growers.

The question of a mechanical cotton picker has exercised the genius of inventors for many years. The difficulty is that the crop does not mature all at once, like wheat, and a picker, human or mechanical, must select the ripe open bolls and leave the others undamaged. The first machines failed in this respect and were also too costly, but other attempts have been made and in 1927 a number of new machines were being tried out with better prospects of success.

Meanwhile a new development had taken place since the World War. Much cotton was lost in the fields through the failure of the bolls to open and a machine was invented by which such bolls could be cracked and the cotton extracted, such cotton being known as bollies. The success of this machine led to a further development. Instead of applying this process only to unopened bolls the experiment was tried of "snapping" off all the ripe bolls from the stalk which is rendered very brittle by the first frost ; and with the improved cleaning machinery it soon became difficult to distinguish such snapped cotton from cotton which had been hand picked. About 1926 this led to a still greater development which contained in it the germs of a revolution. In the great new districts of the Plains and Panhandle the cotton-plant grows very small and, owing to the short growing season, it rarely matures until the first frost, when the whole crop opens at once. It oc curred to someone that the snapping process could be applied to the whole crop by the most primitive kind of machine in the form of a "sled," which was simply a box with a V-shaped slot erected vertically along its centre. Drawn through the field this sled simply tore everything off the plant, but as most of the leaves had fallen after the frost there was nothing left but the bolls, and the result was not much worse than snapped cotton. With further improvement of the cleaning machinery in the gins it turned out that this sledded cotton produced lint which though of a lower grade than hand-pifked cotton was quite merchantable, and under the peculiar conditions existing in 1926 when the price of cotton had fallen to hopelessly unremunerative levels, sledding cotton was practically the only alternative, for the market price even of picked cotton was hardly enough to cover the cost of picking, and in any case the labour supply was entirely inade quate for the huge crop made in the Plains that year. The question whether this method can be extended to other parts of the cotton belt where the character of the plant and the condi tions of harvesting are different in the essential respects, re mained still the subject of acute controversy.

At the same time the growing realization that the conditions under which cotton was being grown were entirely uneconomic owing to the high labour cost had led to efforts to apply mechanical methods to the other operations of cotton growing, and it had been found that where it was possible to apply large scale methods, e.g., by the use of tractors and three or four row cultivators, etc., the cost of production on farms of reasonable size could be materially reduced. It seemed therefore as if the whole future of cotton growing was entering on a new phase.

Other Crops.

The shortage of the American crop had di rected attention primarily to the search for other cottons of about the same staple length. Most of the other principal crops, e.g., Indian or Egyptian, were either distinctly below or above the American, and, as will be seen from the classification table, there was a conspicuous lack of other growths capable of direct substi tution for American. Attention was first turned to the possibil ities of India for the production of cotton a little longer than the normal crop, but progress in that direction was necessarily slow, and in the meantime attention had been directed to other areas, mostly in the American continent, where cotton growing had been long established and the quality was approximately similar to American. The chief of these areas was Brazil, where a commer cial crop of about 600,000 bales was available in addition to a con siderable amount used for purely domestic consumption. The enormous area of Brazil contains a large number of separate cot ton-growing areas which may be roughly classified into two dis tricts, namely southern Brazil (Sao Paulo, etc.), where consider able quantities of cotton of imported American types were grown but were mostly utilized by the local mills. In various districts of northern Brazil (especially Ceara) there was also a consider able crop of cotton of an entirely different type, mostly tree cot tons allied to the long staple Barbadense varieties, and frequently of very good staple, often 14in. and sometimes more. The agricul tural conditions of Brazil as a whole were apparently very favour able for the extension of cotton growing—unlimited land, sufficient rainfall especially in the south, while in the north the tree cottons proved highly drought resistant, with very heavy yields. But in every other respect conditions are far from favourable. The lack of both capital and labour, the uncertainty of political conditions and the traditional unsatisfactory methods of handling the crop were apparently insuperable obstacles to the rapid development of an export crop. Seed selection was almost non-existent, while the habit of mixing different cottons at the gins seriously lowered the commercial value of the better grades, and in spite of the inducement of high prices about 1923 it was doubtful whether any really large increase of the crop was likely.In Peru (crop, about 200,000 bales) the conditions are in most respects entirely different from those of Brazil. The rainfall on the west coast being negligible, cultivation is confined to the nar row valleys of the rivers fed by rains and snow from the moun tains, which provide easy facilities for irrigation. The varieties of cotton originally grown were mostly tree cottons, the chief being known as rough and smooth, the former possessing a pecu liar harsh wiry character which made it particularly suitable for mixing with wool, while smooth was apparently of American origin. In recent years Egyptian cotton had been introduced with some success, though it did not maintain its original character, probably owing to the mixing of the seed and bad handling of the crop. But the chief development was the introduction about 1918 of a new white smooth variety of American origin called Tanguis, which had become very popular during the period of American scarcity and it largely ousted other `growths. In the Trans-Andine districts of Peru there are also large possibilities of developing cotton growing, but the difficulties of the long transport to the river Amazon and thence to the Atlantic made development very slow. General conditions in Peru are much better than in Brazil, transport being facilitated by the numerous small ports and short railways leading up the river valleys, while the conditions of hand ling and marketing the crop are much superior, owing to the fact that the trade is mostly in the hands of a few large European houses.

Other countries in South America with considerable possibilities for cotton growing are Colombia and Venezuela, but the total crops are less than Ioo,000 bales altogether, and are mostly used in domestic consumption. In the Argentine and Paraguay consid erable developments have taken place since the World War, but owing to the lack of labour and experience and the absence of an adequate commercial organization for the handling and marketing of the crop the total is still small, say under 150,000 bales.

British, French and Dutch Guiana (Surinam), especially the last, were once very important sources of supply, but seem to have fallen out almost entirely since the '6os. Almost all of the small republics which constitute Central America have tried cot ton at various times but with no substantial results.

Mexico (crop about 250,000 bales) completes the tale of the Latin-American countries with similar characteristics, namely enormous possibilities, but very small achievements. The area available for cotton growing is probably as large as the whole of the United States cotton belt and offers every variety of condi tion both for irrigation and rain grown cotton. The labour sup ply is ample, but political and economic conditions have always been unfavourable and the crop barely suffices for the needs of the local mills. The north-west corner of Mexico, including the lower end of the Imperial valley, is practically part of the new irrigated area of California, and its crop is so identified with the other that the statistics are generally given along with those of the American crop.

India.

Turning now to those countries the bulk of whose crop is not in Grade II., but which have recently made efforts to increase their contributions to that grade, the most important of these is India. As will be seen from Table II. of the world's crops, the Indian crop is the second largest in the world. The cotton from which the traditional Dacca muslins were made must have been very fine, though it is said to have been of comparatively short staple. Certainly in modern times there is no trace of any cotton in India that could be called long staple in comparison with the other fine cottons of the world, Egyptian and Sea Island, and the bulk of the crop is shorter even than the lowest American staple, say inch. Repeated efforts were made as far back as the days of the East India Company to develop longer stapled cottons in India by the introduction of exotic types, mostly American, but few of these survived. One exception, however, Dharwar American, grown in southern Bombay, has in recent years become the basis of new efforts which have resulted in the development of a really substantial supply of cottcji of about an inch staple, especially in the new irrigated districts of the Punjab. In Madras there have always been finer and longer varieties and these have been supplemented since 190o by further introduction of exotic varieties, especially Cambodia. The result is that since the World War, and partly as a result of the work of the Indian cotton com mittee appointed in 1917, India has been producing a really sub stantial amount—probably i million bales—of cotton of $in. and above, which has found a ready market not only in the Indian mills and those of China and Japan, but also during the years of American scarcity, on the Continent and even in England.

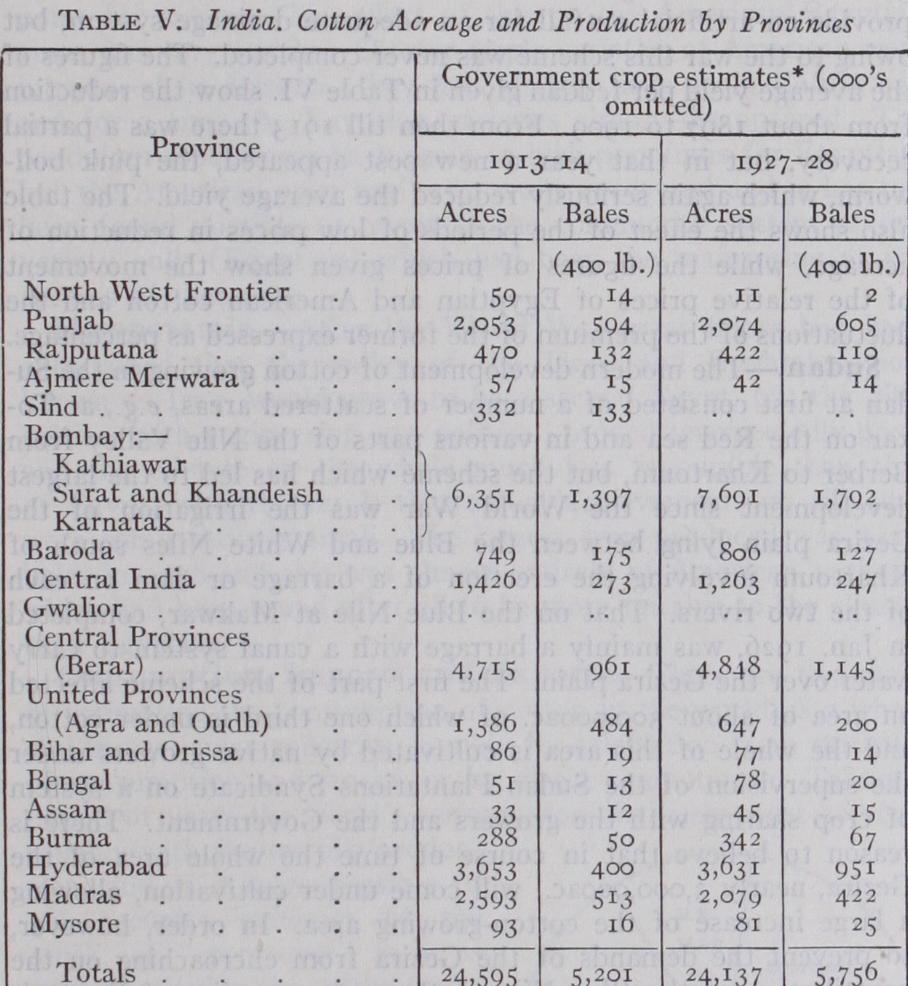

The cotton-growing areas in India are so widely spread and conditions vary so much from one province to another that space prohibits any description in detail, but Table V. shows the acreage and production by provinces.

*The Government crop estimates are generally about 20% lower than 'the estimated commercial crop.

China.—As the bulk of the Indian crop is in Grade III. it is more convenient to deal here with the rest of that grade. Few people are aware that the third largest crop in the world is that of China. Cotton growing is widely spread in many parts of the country, especially in the coastal regions of the north from Tien tsin to Shanghai and the valleys of the rivers Hwangho and Yangtse-Kiang. Unfortunately the statistics available are very unreliable. At times the crop has been put as high as 4 or 5 million bales, but probably 2,000,00o would be nearer the truth. A very large part of the crop is used in purely domestic consump tion, especially for wadded garments. The cotton grown is mainly of the eastern short-staple varieties, but before the World War considerable efforts had been made to develop cottons of Ameri can type, and these had met with substantial success. Little of this cotton, however, found its way into the world's markets, being mostly used in the Chinese and Japanese mills.

Japan formerly had some relatively small areas of cotton grow ing, but since they acquired control of Korea (Chosen) their efforts have been transferred there. As in China the native cotton is of the eastern short-staple varieties, but substantial progress has been made in the development of American types. The total crop probably amounts to about 200,000 bales. There is a number of other small cotton-growing areas in the East Indies, including French Indo-China and Siam, but the total amount is negligible.

Russia.—The greatest modern development of cotton growing in Asia, apart from India, has been in Russia. Russian Turkestan is probably one of the oldest cotton-growing countries in the world and from about the beginning of the loth century much work had been done in reviving its cultivation. Irrigation is essential, the rainfall being negligible; there still exist in the country many ancient irrigation works, some of which have been restored to use, and on the whole the similarity of the conditions to those of Egypt is striking. The crop is widely spread through the provinces of Ferghana, Tashkent, Samarkand, Trans-Caspian, Bokhara and Khiva, and there is another entirely separate area in Transcau casia. In 1915 the crop had reached a total of nearly i i million bales, but the war and the revolution in Russia resulted in abso lute dislocation of the whole economic system of the country which was fatal to the cotton crop of these remote southern dis tricts. They were entirely dependent on the rest of Russia for food supplies and when these supplies disappeared cereals had to be grown in the cotton country, with the resulting reduction of cotton acreage. Since the war recovery has been very slow, as will be seen from Table II., and in 1927 the total was still far short of the 1915 record. The cotton grown was again mainly of the Asiatic short-staple varieties, but in certain districts a good deal of American had been grown before the World War. Prac tically the whole of the crop went to the Russian mills. In Persia and Afghanistan small quantities of cotton had also been grown before the World War, the former finding its way through Russian channels and the latter through India. In Asia Minor, the Ger mans before the war had developed two promising cotton-growing areas, namely in the Cilician Plain near Adana and at Aidin near Smyrna. A little cotton had also been grown in Syria, and men tion may also be made of various small areas in Cyprus, Crete, Malta and various European settlements along the north coast of Africa and even in some parts of southern Europe, Turkey, Bulgaria, Albania, Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy and Spain.

Africa.—Returning to Grade II. the most interesting develop ment of the loth century has been Africa, largely as the result of the work done by the British Cotton Growing Association and other similar organizations developed by European countries which have colonies in that area, namely France, Germany, Bel gium, Portugal and Italy.

In West Africa the first experiments were made in the form of large estates run by Europeans with wage-paid native labour, but this was soon abandoned in favour of the policy of independent native growers, while the association undertook the work of seed supply and distribution and the ginning, baling and export of the crop.

Many areas in West Africa have been tested, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, Gambia, etc., but latterly efforts have been concen trated in Nigeria, where substantial results have been achieved, the crop in 1925 being 40,00o bales of Soo lb. The native varieties are mostly short staple and are at a disadvantage owing to the very small outturn (percentage of lint to seed cotton), but efforts to introduce more profitable varieties of American type have latterly achieved considerable success, especially in northern Nigeria.

Since the war the work of the Association has been extended to Uganda, which has now achieved the largest single crop of any one district in Africa except Egypt (157,00o bales of Soo lb. in 1924), and also to Tanganyika, Nyasaland, northern and southern Rhodesia. In the Union of South Africa after the war consider able expansion of cotton growing took place, but labour and other climatic conditions there are very different from most of the others above mentioned and success on a really large scale is problematical. Other European Powers have developed cotton growing in their African possessions with varying degrees of success.

Fine Cotton.

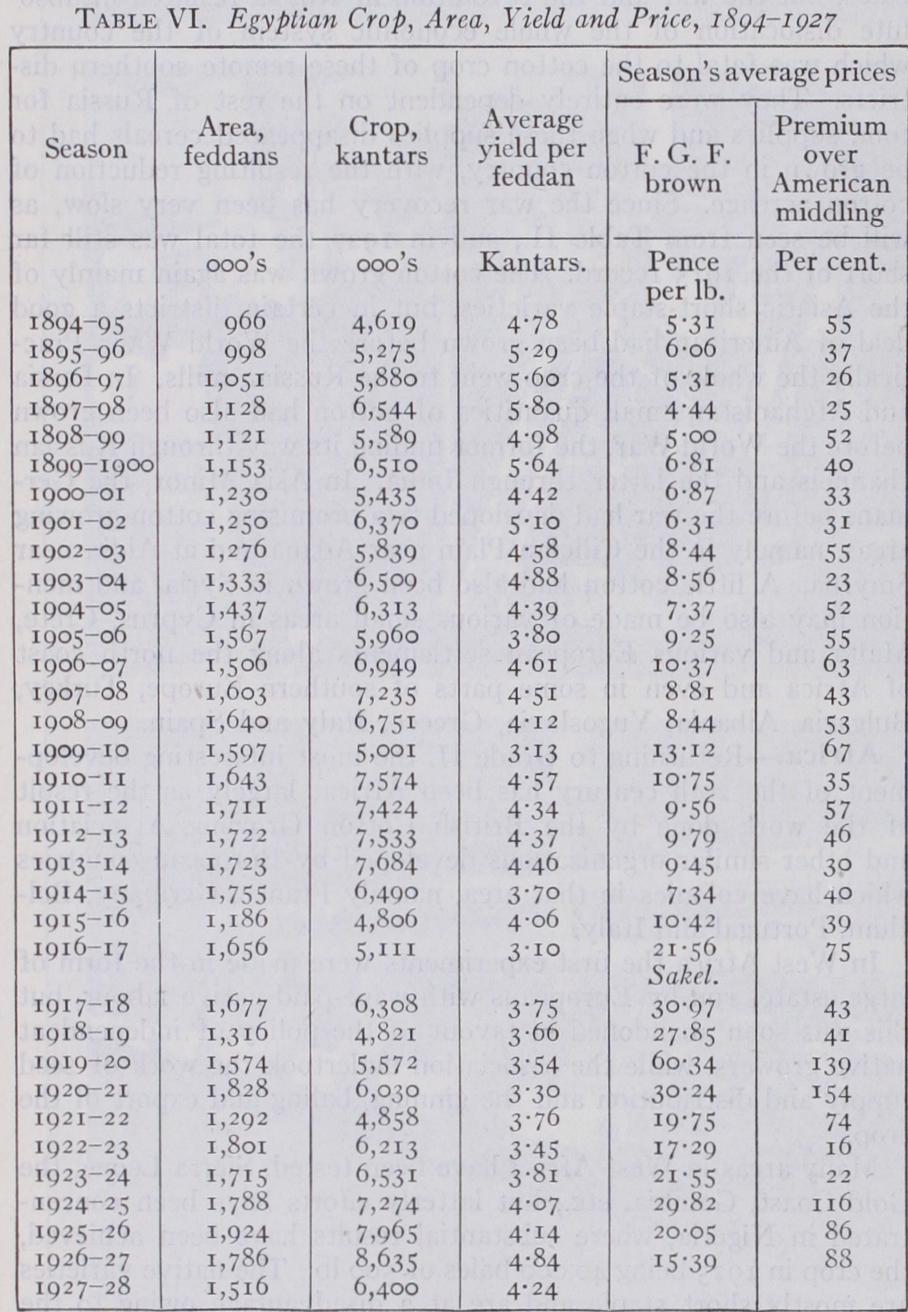

Prior to the World War the finest cotton in the world was supplied mainly from the Sea Island districts of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, the crop fluctuating between 6o,000 and 120,000 bales, but this crop was practically wiped out by the advent of the boll weevil to these districts about 1918 and since then the only supplies of this superfine cotton have been from the British West Indies. Before the war these had amounted to 6,000 bales, but they also suffered very severely during the war from the competition of sugar and have ever since then been more than 5,000 bales. Some of the other West Indian islands belonging to foreign Powers (now including the United States) also produce small quantities of good Sea Island, and certain other islands in the Pacific, Hawaii, Fiji, Tahiti, etc., also produce small quantities. The main bulk, however, of the fine cotton supplies now consists of Egyptian cotton. The total cultivable area of Egypt is less than 6,000,000 acres and of this nearly 2,000,000 were under cotton in 1925. Table VI. gives the history of the crop since 1894 A f eddan =1-038 acres; kantar = 99 • 049 lb.

As rainfall in Egypt is almost negligible except near the sea, cotton growing is entirely under irrigation. The history of the modern irrigation system dates from the introduction of the mod ern Egyptian cotton about 182o. At that time the system was entirely what is known as "basin" irrigation, under which the whole cultivable area was divided into great basins of about 40,000 acres each divided off by great earthen banks, and into these the flood waters were carried by short canals producing complete sub mersion during the period of the flood, after which the water was run off again as the level in the main channel of the Nile fell. This system, however, rendered cotton growing impossible and "perennial" irrigation was introduced under which a limited supply is given throughout the whole year. The history of the modern irrigation system may be divided into three periods : (I) up to 1885 when the great barrage at the bifurcation of the two branches of the Nile just below Cairo (which had been begun under Mohammed Ali in 1842) was repaired and completed by British engineers; this rendered possible the full utilization of the natural supply in the Nile ; (2) the next stage was the erection of the Aswan Dam completed in 1902, a great storage reservoir which is filled at the close of the flood and held until the following spring, when it is doled out through the summer by the system of "rotations" to maintain the level of the river and the great canals leading from the barrage. Other barrages were also erected at Esna and Assiut to feed similar canal systems in Upper Egypt and at Zifta on the Damietta branch below the Cairo barrage to feed a supplementary system of canals in the Delta ; (3) the addi tional supply thus provided having proved insufficient the Aswan Dam was raised in 1912. In the meantime the extension of per ennial irrigation and the increase of the supply, accompanied by an insufficient provision of drainage, had raised the subsoil water table in the lower parts of the Delta and in 19o9 a peculiar com bination of flood conditions brought matters to a head and caused colossal damage to the crop of that year. After prolonged con troversy a great scheme was inaugurated by Lord Kitchener to remedy the lack of drainage by enclosing and pumping out the great salt lakes along the Mediterranean coast, which would then provide an artificial outfall for an adequate drainage system, but owing to the war this scheme was never completed. The figures of the average yield per feddan given in Table VI. show the reduction from about 1897 to 1909. From then till 1913 there was a partial recovery, but in that year a new pest appeared, the pink boll worm, which again seriously reduced the average yield. The table also shows the effect of the periods of low prices in reduction of acreage, while the figures of prices given show the movement of the relative prices of Egyptian and American cotton and the fluctuations of the premium of the former expressed as percentage.

Sudan.—The modern development of cotton growing in the Su dan at first consisted of a number of scattered areas, e.g., at To kar on the Red sea and in various parts of the Nile Valley from Berber to Khartoum, but the scheme which has led to the largest development since the World War was the irrigation of the Gezira plain lying between the Blue and White Niles south of Khartoum involving the erection of a barrage or dam on each of the two rivers. That on the Blue Nile at Makwar, completed in Jan. 1926, was mainly a barrage with a canal system to carry water over the Gezira plain. The first part of the scheme affected an area of about 30o,000ac. of which one third is under cotton, and the whole of this area is cultivated by native growers under the supervision of the Sudan Plantations Syndicate on a system of crop sharing with the growers and the Government. There is reason to believe that in course of time the whole area of the Gezira, nearly 3,00o,000ac., will come under cultivation, allowing a large increase of the cotton-growing area. In order, however, to prevent the demands of the Gezira from encroaching on the contribution of the Blue Nile to the water supplies of Egypt it will be necessary to convert Lake Tsana, across the Abyssinian border, into a great storage reservoir, and negotiations with the Abyssinian Government for this purpose had been going on for some years before 1927.

The dam on the White Nile at Gebel Auli just south of Khar toum is to supplement the irrigation system of Egypt by holding back the flood waters of the White Nile till after the crest of the Blue Nile has passed Khartoum, thus prolonging the period of the flood in the main Nile and at the same time reducing the danger of the flood from being too high for the banks which con fine the river in its course through Egypt. In course of time it may be necessary to supplement this further by controlling the waters in the upper regions of the White Nile and finally perhaps by converting its main source, the Victoria Nyanza, in Uganda, into a further storage reservoir. When that is finished the whole system of the White Nile from the sea to Abyssinia and Uganda will become one huge irrigation unit.

In 1927 the great bulk of the crop grown in the Sudan was of the Egyptian Sakel varieties and of very good quality, but in certain smaller districts on the River Nile American varieties had been found more suitable to the climate. In the far south of the Sudan there are also great possibilities for the development of rain-grown cotton where the climate again changes to monsoon type, but this will probably have to wait until the development of the irrigated districts has made further progress.

American-Egyptian.

In the detached districts lying towards the west coast of the United States, namely the Salt River valley of Arizona and the Imperial valley of California great irrigation developments had taken place before the World War which nat urally suggested the cultivation of Egyptian cotton and for a time this met with substantial success, though against considerable difficulties; e.g., the heavy cost of picking owing to the less open character of the boll. In 192o the total crop of these areas, including a number of other smaller valleys, had reached a total of 91,691 bales. This development was greatly favoured by the heavy premium on Egyptian cotton during the years 1919 and 1920 which resulted from the inordinate demand by America for Egyptian cotton for use in motor car tyre fabric. This, however, brought its own remedy, compelling the tyre makers to find ways of making the fabric from less expensive cotton, e.g., Peru vian, long staple American, etc., but this was followed by a reac tion in 1923 when the peculiar conditions of the American market resulted in the premium on Egyptian falling almost to vanishing point for a time. The effect of this on the American Egyptian areas was very serious. Shorter staple varieties of American were introduced in Arizona (they had already been so in California) and for a time the Egyptian varieties almost disappeared. The pendulum soon swung back again to high premiums for Egyptian, but the American crop has never quite recovered and it has not been found possible to revert to the community system of one variety only (Egyptian) which had been the mainspring of the success of that crop.the World War great hopes had been entertained that the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, now known as Iraq, would prove to be a second Egypt, but the diffi culties, both engineering and political, proved unexpectedly great and the climate on the whole much less favourable than that of Egypt, with the result that actual 'achievements up till 1927 were comparatively small. The largest crop produced was 3,000 bales in 1926 and this was almost entirely of American varieties which had been found after all to be more suitable to the climate than Egyptian.

Consumption, Imports and Exports.

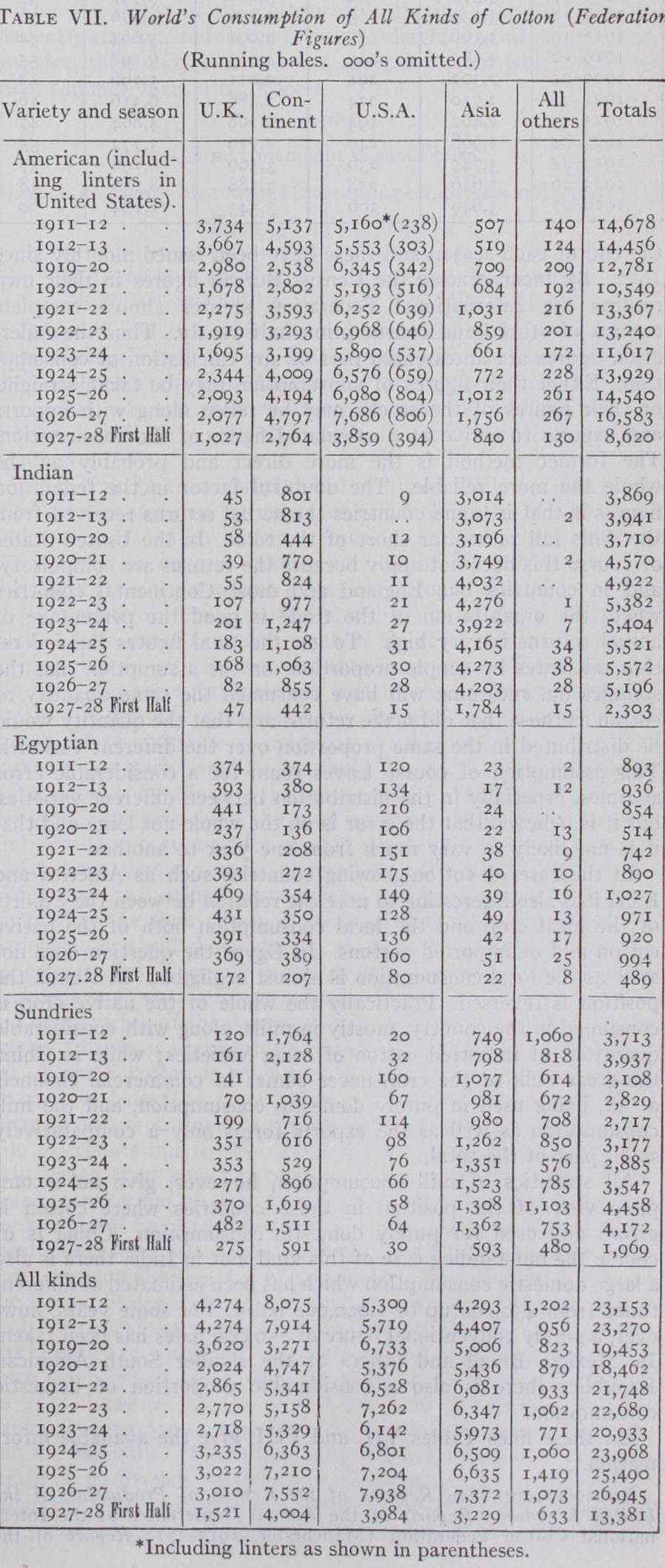

There are two ways of estimating the consumption of cotton in the world as a whole and in particular countries, namely by calculation from statistics of consumption and stocks, or by direct computation. Taking a period of years the world's consumption obviously must coincide roughly with the world's produc tion, and if it were possible to get accurate statistics of the stock, or "carry-over" as it is usually called in the cotton trade, at the end of each season, that would be the most correct guide to consumption. Unfor tunately these carry-over statis tics, even in the case of Ameri can and Egyptian where the information most nearly ap proaches completeness, are sub ject to a good deal of con troversy and include a number of doubtful items of which, however, the total is relatively small. In the case of Indian the carry-over figures are still more difficult, while for all the other varieties included in what are known in Liv erpool as "outside growths" there are hardly any statistics at all, especially as to the stocks in the countries where they are grown.In the case of those countries which do not produce cotton, such as Great Britain, the corresponding method of taking the imports less re-exports and allowing for stocks should be a good guide to consumption ; but again the stocks in mills as well as at the ports and in warehouses must be arrived at, and that can only be done by direct computation. The compilation of statistics of stocks at ports and in warehouses is fairly easy, but the com pilation of mill stocks could not be undertaken until the estab lishment of the International Federation of Master Cotton Spin ners' and Manufacturers' Associations provided an organization which represented the bulk of the cotton mills in every important cotton-spinning country throughout the world except America. From 1905 the federation published half-yearly statistics of mill stocks. In the United States the Census Bureau of the Depart ment of Commerce has for many years published statistics of stocks in public warehouses and in consuming establishments at the end of each season and these have been issued monthly since 1912. By incorporating the Census Bureau figures in their own returns the International Federation secures almost complete returns of stocks and consumption half yearly. Thus the feder ation figures are an essential part of any calculation of consump tion. Either their figures of consumption may be taken straight, or their figures of the stocks may be taken along with imports and exports to arrive at a calculated figure of the consumption. The former method is the more direct and probably on the whole the more reliable. The doubtful factor in the federation figures is that in some countries the actual returns received from the mills fall rather far short of the total. In the United States of course this does not apply because the returns are compulsory, and in countries like England and most Continental countries where the organization of the trade is good the percentage of actual returns is very high. To get the total figures the federa tion calculates by simple proportion, on the assumption that the spindles not returning will have consumed the same quantity of cotton as those that did make returns and that the quantity would be distributed in the same proportion over the different varieties. This assumption of course leaves room for a considerable error at times, especially in the distribution between different varieties, but it is believed that the error is on the whole not large and that it is not likely to vary much from one year to another.

In the case of cotton-growing countries such as America and India it is also interesting to note the relation between the exports of the local crop and the local consumption both of the native cotton and of imported cottons. In Egypt the question does not arise as the local consumption is almost negligible. In Russia the position is reversed. Practically the whole of the native crop is consumed in the country, mostly in mills, along with considerable quantities of imported cotton of other varieties; while in China the great bulk of the crop never comes in commercial channels at all, being used in purely domestic consumption, and the mill consumption as well as the exports forms only a comparatively small part of the total.

All statistics of mill consumption, however, give an incom plete view of the position in those countries where cotton is grown and used for purely domestic consumption. China is of course the outstanding case of this kind, but in India there is also a large domestic consumption which has been estimated at different times from 450,000 up to I,000,000 bales. For some years, how ever, a purely conventional figure of 750,000 bales has been taken. In Mexico, Brazil and others of the smaller South American Republics there is also a considerable proportion of domestic consumption.

On these lines Tables VII. and VIII. give the available infor mation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-See

Reports of the Census of Production of the Bibliography.-See Reports of the Census of Production of the United Kingdom; Reports of the Annual Conferences of the Inter national Cotton Federation (Manchester, 1915-27) ; Report of the Board of Trade Committee on the position of the Textile Trade after the World War (Cd. 907o, 1918) ; Report of the Empire Cot ton Growing Committee (Cd. 523, 1919) ; Report of the Indian Cotton Committee (Calcutta, 1919) ; W. L. Balls, Handbook of Spinning Tests for Cotton Growers (192o) and A Method for Measur ing the Length of Cotton Hairs (1921) ; Reports of the British Cotton Growing Association (Oldham, 1922 et seq.) • International Cotton Bulletin (Manchester, 1922 et seq.) ; J. A. Todd, The World's Cotton Crops (reprinted 1923) ; Empire Cotton Growing Review (1924 et seq.) ; J. Hubback, Cotton Growing Countries, Present and Potential (Intern. Inst. of Agric., Rome, 1926) ; W. H. Hubbard, Cotton and the Cotton Market (2nd ed., 1927) ; "Cotton Futures," Cotton Year Book 1927; J. A. Todd, The Cotton World (1927) . (J. A. T.) The cotton crop enters largely into international trade, influenc ing balances of trade, foreign exchanges and the purchasing power of nations. It is not unnatural that such a crop, grown in many different countries varying widely in agricultural efficiency, in dustrial and commercial' development and transport facility, should be marketed and financed by many different methods. Broad descriptions on this subject are therefore dangerous, for the infinite variety of local circumstances may provide innumerable exceptions to any explanation of the system which is most general in one country or one cotton-growing district.The progress of cotton from the planter to the spinner, who may be in the same or another country, may conveniently be divided into two sections. Each year as the cotton crop ripens and is picked, the first task is that of collection from the numerous growers, and the concentration of the new crop at centres which are conveniently placed within the cotton-growing area. This process of local marketing is the first important phase in the transfer of cotton towards the final consumer. It is a process which in most countries is carried out along lines which are curi ously unscientific and perhaps wasteful. To a very great extent this is due to the conditions under which the world's cotton crop is grown. The bulk of it is grown on farms which are very small in acreage. The average size of holding of cotton growers in the United States is not more than eight to nine ac. where labour is scarce and 3o-4oac. where much machinery is used. In Egypt the average holding is about three feddans and there is a con tinual tendency towards subdivision. In India, where agricultural production is based upon the needs of the family, the holding ranges from about eight cultivated acres in Madras to a half cultivated acre in the more densely populated parts of Bihar. When it is further recollected that the majority of these cotton growers are illiterate, uneducated men with little or no capital, the importance of and necessity for the middleman, providing capital and means of collection, storage and ginning, becomes ap parent. The multitude of growers demands an army of middle men. Neither are the functions of such middlemen confined to an interest in the crop from the time of picking. Middlemen, in a variety of ways in different countries, help in large measure to finance the actually growing crop. The average grower often has so little capital reserve that he must find someone who will finance him in the purchase of seed, manure, machinery and, in a degree which will depend upon the financial strength of the middleman and the extent to which the local or central banks will grant advances upon the ultimate security of a growing crop, it is often the merchant who aids in this early stage.

Important as is the material collection of each annual cotton crop at the network of small markets and finally within a smaller number of larger spot markets the second process, in the final disposal of the crop, is even more important in the determination of the price at which cotton will ultimately find its way into the hands of the spinner. This is the set of transactions which takes place upon the organized cotton markets in the world—Liverpool, New York, Alexandria, New Orleans and Chicago—where wide spread dealings in future contracts in effect create one market for cotton with prices from hour to hour reacting sympathetically in every country in the world. Lest this division of the subject which has been made into local marketing and the transactions of the large future markets cause misunderstanding it ought to be made clear that the two processes do not necessarily succeed each other chronologically. Contracts for the future delivery of cotton may, of course, be made, either on or off exchanges for very many months in advance and, in the big exchanges, a regular commerce exists in such contracts relating to each of the succeeding 12 months. The crop, in effect, is being bought and sold and its probable quality and quantity influencing existing prices long be fore it arrives at the local market. But for more detailed descrip tion it is necessary to consider each important growing country in turn.