Animal Distribution in the Sea

ANIMAL DISTRIBUTION IN THE SEA The distribution of life in the sea is dependent on factors partly physical, partly chemical. Density and viscosity are the primary factors governing the floating of organisms in the water. (See PLANKTON.) The pressure of the water increases with the depth. A column of sea water of average density measuring 10.07 metres exerts a pressure of one atmosphere per sq.m. of surface, so that in the greatest known depths of the ocean (10,793 metres), a pressure of almost 1,072 atmospheres prevails. The pressure of the water, however, has no perceptible influence on the distribu tion of the animals. Animal life is present at great depths, and the plankton and fishes of the open sea may undertake, in one night, vertical migrations of 30o metres and more without being injured by alteration of the pressure by about 3o atmospheres.

The brittle star Ophiocten sericeum, is present in depths varying from 6 to 4,370 metres; it is eurybathic. Species confined to particular depths are termed stenobathic; e.g., the reef-building corals, which flourish only to a depth of 3o metres.

Waves.—The movements of the water, which at different times and places undergo many changes, are of particular importance to animal life. Waves reach to depths of several hundred metres. Currents may reach similar depths. The breakers make a heavy demand on the coastal dwellers; in the North sea the strength of their impact averages 15 tons per sq. metre. Animals dwelling on rocky coasts within the region of the breakers must protect them selves from injury. This is accomplished either by the animals attaching themselves to the substratum, or by the formation of strong shells. As examples of fixed animals the acorn-shells (Balanus) may be mentioned; others which adhere by a strong foot are the gastropods (Patella, Littorina); the mussel Mytilus anchors itself by its byssus threads. In the deeper layers where movements are felt, sessile animals are able to bend, and have some elasticity of movement ; in still waters they are rigid; e.g., the Bryozoon, Caberea boryi, in the North sea. Marine currents are very important for the distribution of fixed animals, since they serve as means of transport for the free-living larvae.

Temperature.—Temperature is very important. The tem perature of the surface water decreases, in general, towards the poles, but this is modified by warm and cold currents. The tem perature decreases, also, with depth, and at the bottom is down to about zero. Owing to the great surface currents, more water is carried towards the poles than away from them, and, as the cold water at the poles is heavier than the water of the equatorial regions, there is a steady shifting of the deeper layers towards the equator. These cold, deep currents cannot penetrate secondary seas separated from the main ocean by ledges not far below the surface.

Related animals show marked variations under the influence of differences of temperature. Frequently the size of individuals of the same species increases with decreasing temperature towards the poles and in deep water layers. The shell of the gastropod Nassa clausa reaches a height of I2.7MM. in the Skagerak; at Spitzbergen it measures 38mm. Similarly, the Isopod, Serolis bromleyana, measures i6mm. at depths of 73o metres, and at 3,600 metres, 54mm. Giant species, i.e., species which greatly ex ceed in size related forms, are found comparatively frequently in polar seas and in deep water. This may be ascribed to the influ ence of temperature. The hydropolyp, Branchiocerianthus imper ator, which attains a height of 2 metres in depths of more than 3,000 metres, is an example. Other effects of low temperature are the greater amount of yolk in the eggs, and the frequent occur rence of brood-nursing. The multitude of brood-nursing forms in all classes of echinoderms in the Arctic and Antarctic is re markable. It is noteworthy that the annelid Cirratulus cirratus, which in temperate seas deposits its eggs, at the Falkland islands practises brood-nursing.

The cold waters of the Arctic and the Antarctic are sharply divided from one another by warmer seas. To many cold-steno thermal animals this barrier is insuperable. Eurythermal animals may, indeed, be distributed through all seas, notwithstanding the variety of temperature. The fact that many species present at both poles are absent in the intervening regions has attracted particular attention. Since, in general, the area of a species is continuous, this bi-polarity requires explanation. Bi-polarity of species is by no means common. Some apparently bi-polar species are found in the intervening regions in the cold deep strata, e.g., Calanus finmarchicus. In other instances the two polar forms are also related to a species found in the intermediate region. Thus, the bi-polar Foraminiferan Globigerina pachyderma is re lated to G. dutertrei of warm seas. Bi-polar species, therefore, are derived from cosmopolitan through parallel modification of periph eral forms under the influence of environment.

Chemical Composition.

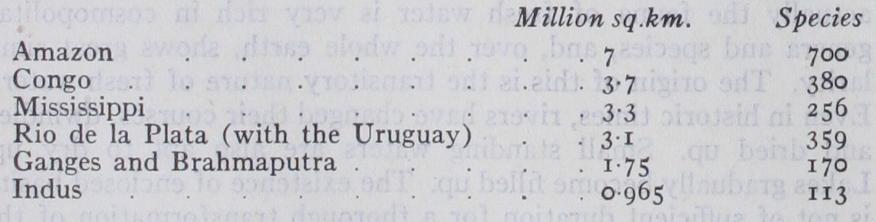

The chemical composition of the sea is very uniform, in consequence of the general mingling of the Iv.) ters. The salinity at a depth cf 3oo metres is about 35, but is lower in surface water in estuaries, and in polar regions when the ice is melting. Considerable variations in salinity are found only in secondary seas shut off from the general mixture of the waters. These have a higher or lower salinity according to the ratio between the amount of river-water received and the amount of evaporation taking place. The Red sea has a high salinity (over 4o%), so has the Mediterranean (38%) ; the Baltic has a low salinity. In the Baltic the influence on the animal popula tion of the decrease in salinity is very striking. The number of species decreases, in proportion to the decrease in salinity, in an easterly direction (see Table).

The size of the species also decreases in the same direction. The edible mussel (Mytilus edulis) at Kiel, attains a length of riomm., further in the Baltic, it measures over 5omm., in the Gulf of Fin land 27mm., in the Gulf of Bothnia, 2IMM.

The quantity of carbon dioxide, nitrogenous salts and other ma terials necessary to plants in the water of any region is particu larly important in determining the amount of life. If these ma terials are abundant, plant life flourishes and consequently animals find plenty of food. The sources of this food are, first, the products of animal metabolism and of the disintegration of dead organisms. Carbon dioxide and nitrogenous salts are only of use, however, in the upper, illuminated strata of the water, where the light is sufficient to supply energy for the assimilation processes of plants. The dead bodies of organisms which inhabit the open sea sink to the bottom, and, in great depths of the ocean, are withdrawn from the metabolic cycle. Their disintegration pro ducts can be used only in shallow seas where mixture of the water takes place right down to the bottom. In deep seas they may be of use in places where rising currents bring water from the depths to the surface. It happens, therefore, that coastal regions, shallow seas like the North sea, and banks such as the Dogger, show great wealth of life. Rising currents are found chiefly on the west coasts of continents where, owing to prevailing winds off the land, the surface water is driven away from the coast, and a compensating current from the depths flows towards it. No sea water is so teem ing with life as those currents which set in towards the land in tropical regions, e.g., off the coasts of Portugal and Chili. A quan tity of fertilizing matter for plants is brought down to the sea, particularly by rivers. The region most richly supplied with river water is the Atlantic-Arctic, into which more than half the earth's surface is drained. The Pacific is the poorest in this respect, particularly in its eastern portion. This, with its great depth, accounts for the poverty of its life compared with other oceans.

Oxygen is present everywhere in sufficient quantity in the sur face waters of the open sea. In the depths, the influx of currents of polar surface water brings sufficient oxygen, and, since the disintegration of dead organisms goes on very slowly in the cold water of these depths, this oxygen is not used up in the process. In secondary seas where such currents are absent matters are different. In the eastern Mediterranean, the deeper layers of the water lack oxygen, and have a large quantity of carbon dioxide; on this account they contain hardly any life. This also applies to the greatest depths of the Baltic. In the Black sea, some Nor wegian fjords, and in Walfisch bay on the west coast of Africa, the bottom water contains sulphuretted hydrogen produced by the disintegration of organic remains.

The Zones of Life in the Sea.

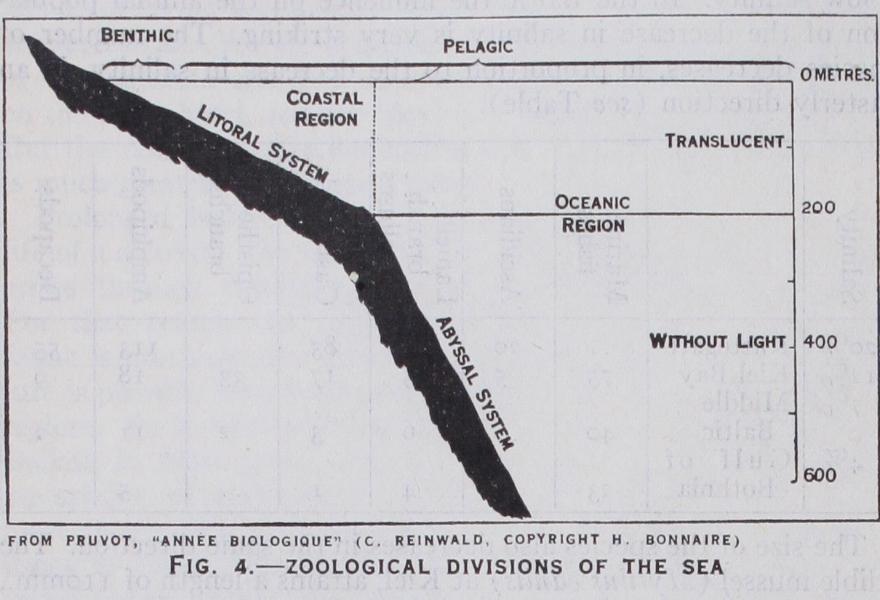

In the biocycle "the sea" two principal regions may be distinguished. These differ completely in their conditions of life, and, therefore, in their animal popula tion also (fig. 4). They are the "benthic region" (floor of the sea), and the "pelagic region" (open sea). The benthic fauna consists of animals attached to the sea bottom. Pelagic animals are not attached to the bottom, and maintain themselves floating or swimming in the water. Benthic and pelagic regions can be sub divided into two areas, that penetrated by light (on an average from the surface down to 200 metres), and a dark or abyssal region. The illuminated portion of the benthic region is termed the "littoral zone." Littoral Zone.—In the littoral zone the bottom may be firm or shifting. A shifting bottom shows a flat surface, and varies accord ing to its constituents, gravel, sand or mud. Rocks form a hard bottom, and the coast in such places is generally precipitous. The kinds of animals found in the littoral are determined by the type of bottom and by the movements of the water. The littoral is divided into three zones according to the movements of the water; (I) the tidal zone, between high and low tide marks, (2) the shal low water zone, or region affected by the waves, (3) the still water zone, which extends from the shallow water zone to the upper limit of the abyssal region.

A stony shore in the tidal zone is almost entirely without life, all organisms being killed by friction of the stones against one another. In shallow water, sandy bottoms which are of ten dis turbed are not inhabitable for many animals. In places, however, where plants (Zostera, Posidonia) flourish, the sand is bound together, and animals find hiding places under the leaves and among the roots ; sessile animals can find places for attachment ; food (mud, detritus) is present, so that here a characteristic fauna is established. In deeper water, and in the shelter of projecting islands and sandbanks, a rich fauna may develop also near the surface, on sand and ooze. Sessile animals, certainly, are not often found on shifting bottoms, owing to the danger of being buried; but oysters settle on the shells of molluscs, or on stones, and the edible mussel (Mytilus) attaches itself by its byssus to the float ing branches of Fucus. On the other hand, shifting bottoms teem with animals which burrow under the surface, and so render them selves invisible to enemies. Such are the lob-worm (Arenicola), and other annelids, Balanoglossus, the heart urchin (Echinocar dium), and numerous bivalves, which usually have smooth, flat shells for digging, and which obtain food and oxygen from the surface by siphons (fig. 5) . These are followed into the sand by the starfish Astropecten aurantiacus and the predatory snail Natica. Crustaceans, amphipods, shrimps and the lancelet, Am phioxus, also burrow in the sand. Flat fishes, the star-gazer (Uranoscopus), weever (Trachinus) and blenny (Blennius) work themselves in just beneath the surface, gazing upwards with eyes situated on the upper surface of the head. The sand shelters also minute animals which find room for movement between the sand grains :—acoelous Turbellarians, Archi-Annelida, Tardigrada and Gasterotricha. The principal animals found on the sand are the ophiuroids, some gastropods (Turritella, Aporrhais), annelids and crabs.

Rocky coasts, in contrast to flat, shifting bottoms, offer a firm substratum for plants (particularly Laminaria and Fucus), and for sessile animals. Clefts, holes and caves offer shelter from the force of the waves. Sessile animals fix themselves by preference to the kelp, and to its places of attachment. Some construct hid ing-places by boring holes in the rocks, e.g., the boring sponge, Vioa, the boring bivalves Pholas and Lithodomus, and sea urchins such as Strongylocentrotus. Those animals, however, which dwell upon the rock surface, are armoured and protected against attack by hard shells or by weapons. Sponges have sharp spicules of silica, polyps and Anthozoa stinging-cells (cnidoblasts), echino derms spiny armour, snails and bivalves strong, often spiny shells. Many crustaceans on rocky bottoms have spiny cuticles; some, however, hide themselves by placing algae, sponges, or polyps on their backs, while some of the fishes have poisonous spines (Scorpaena). Animals dwelling within the region of the breakers require protection against the battering of the waves, and so are firmly attached (see above). This region exercises a keen selective influence ; only a few species can withstand the force of the waves, but this affords them protection from enemies. Thus the edible mussel (Mytilus) has a wide distribution in the littoral region, but usually is represented by solitary individuals; in the region of the breakers, however, where they are not exposed to attack, mussels are packed together in large numbers.

Coral reefs may be compared to rocky coasts. They consist of the dwellings of the reef-building corals, which attach themselves to the firm substratum, and offer dwellings and hiding places for many kinds of animals. These reefs are confined to a belt in the tropical seas, extending from 30° N. to 2 7 ° S., since the coral polyps require a temperature of at least 20.5° C. This accounts for their absence on the west coasts of Africa and America, where cold currents set in towards the shore. Calcareous algae, Bryozoa, some gastropods and other organisms take part with the corals in the formation of the reef. Reef-building corals cannot live below a depth of about 3o metres, since they live in symbiosis with algae (Zooxantliella), which inhabit the walls of the enteron of the polyp, and require light for assimilation. The delicate colours of corals are obtained from the algae. All reef-dwelling animals have vivid colours (Plate I.) .

The numerous species of corals of which a reef is composed are so arranged that in the zone of the breakers, strong, resistant forms are found. In deeper water, and in places where there is shelter from the waves, the delicately tinted, branching forms occur. Many kinds of ani mals find retreats in the numer ous holes and cavities of the reefs, among them worms, crusta ceans, gastropods and fishes.

Some fishes feed on the coral polyps, and bite the ends of the branches with their beak-like jaws (Pomacentridae and Plec tognathae).

Pelagic Zone.

The inhabit ants of the open water or pelagic region have common peculi arities connected with floating. Living matter is somewhat heavier than seawater ; therefore, to float, animals must possess special adaptations. The rapidity with which a body sinks varies in proportion to its weight. It decreases with increased form-resistance (such as expansion of the under-surface) : The weight of a living organism is lessened by the sparing use of skeletal material (lime, silica), and by the accumulation of lighter substances (fat, air) in the body. The shells of floating animals, therefore, are small and thin, as in pelagic Foraminifera. The phosphorescent animal Noctiluca, many free-swimming crusta ceans, the eggs of pelagic fish (e.g., cod, flat fishes) contain fat globules ; further, the accumulation of fat in the liver of many fishes, and the blubber of penguins, seals and whales lessens the effective weight. Air-bladders are the most effective means of diminishing weight, and are found in many Siphonophora and in bony fishes (Teleosteans). Form-resistance is increased by en largement of the under-surface. The most usual way is by ab sorption of sea-water into the body. This does not increase the weight, but distributes it over a greater area. Thus arises the gelatinous tissue frequent in pelagic animals. Water forms 96% of the jelly-fish, Aurelia aurita. In small animals, the under surface may be increased by flattening the body, or by horizon tally disposed processes which serve as floats ; e.g., pelagic nemer tines (flattened like cakes), the Phyllosoma-larvae of crustaceans, copepods (Sapphirina). If such means do not suffice, movements are made to assist in the prevention of sinking, as the lashing of the cilia of pelagic larvae and turbellarians, the beating of the ciliated plates of Ctenophora, the muscular movements of anne lids, and crustaceans. Swimming occurs when the muscular move ments are sufficiently strong to render the animal's path inde pendent of the movements of the water. Swimming is almost entirely confined to fishes, some cuttlefishes, and animals not primarily marine, such as turtles, penguins, whales and seals.Those living organisms which float free in the water are termed the plankton (q.v.). The constitution of the plankton of the open sea differs from that of the coastal regions, or of shallow seas. The oceanic plankton consists entirely of forms which pass their whole life floating in the water (holoplanktonic). Examples are Siphonophora, Ctenophora, Chaetognatha, some crustaceans and gastropods, salps, and the ascidian, Pyrosoma. In coastal regions, in addition to such holoplanktonic forms, there are numerous ani mals pelagic only at some period of their life (meroplanktonic), in particular, the larval forms of benthic animals. The composi tion of the coastal plankton is therefore much more changeable than that of the oceanic plankton. The coastal plankton has its lower limit at a depth of zoo metres, but it may be driven beyond this by storms or currents. Coastal waters are much richer in life than oceanic. In the open ocean, however, the amount of life is not the same in all parts. In the Atlantic, the polar regions are much richer than the tropical. The poorest catch in the tropi cal Atlantic contained 763 organisms per litre of water, the richest catch in cold waters 76,915. There are, however, stretches of trop ical seas which have a rich plankton, such as parts of the Indian ocean. The plankton forms the food of many fishes, such as her rings.