Approach Channels

APPROACH CHANNELS The accessibility of a port depends upon several factors, such as the depth of its approach channel, which also determines the depth of the docks or basins to which it leads, f or it is useless to give a depth to a dock much in excess of the depth down to which there is a prospect of carrying the channel by which it is reached. The great augmentation, however, in the power and capacity of modern dredgers, and especially of suction dredgers not only in sand but also in soft clay, together with the increasing draught of vessels, has resulted in a considerable increase being made in the available depth of rivers and channels leading to docks.

It is theref ore necessary to make due allowance f or the possi bility of a reasonable improvement in determining the depth to be given to a new dock. On the other hand, there is a limit to the deepening of an approach channel, depending upon its length, the local conditions as regards silting, and the resources and prospects of trade of the port, f or every addition to the depth generally involves a corresponding increase in the cost of maintenance.

In Tidal Ports.

At tidal ports the maximum available depth f or vessels should be reckoned from high water of the lowest neap tides, as the standard which is certain to be reached at high tide. The period during which docks can be entered at each tide depends upon the nature of the approach channel, the extent of the tidal range, and the manner in which the entrance to the docks is effected. Thus, where the tidal range is very large, as in the Severn estuary, the approach channels to some of the South Wales ports are nearly dry at low water of spring tides. It would be imprac ticable to make these ports accessible near low tide, except f or small craf t, whereas at high water, even of neap tides, vessels of large draught can enter the docks. Nevertheless, in recent years, it has become increasingly important to provide in tidal ports channels of sufficient depth to permit the access of large ships to the closed docks at all states of the tide and this has been effected at many ports such as Liverpool, London and Havre.

Liverpool.

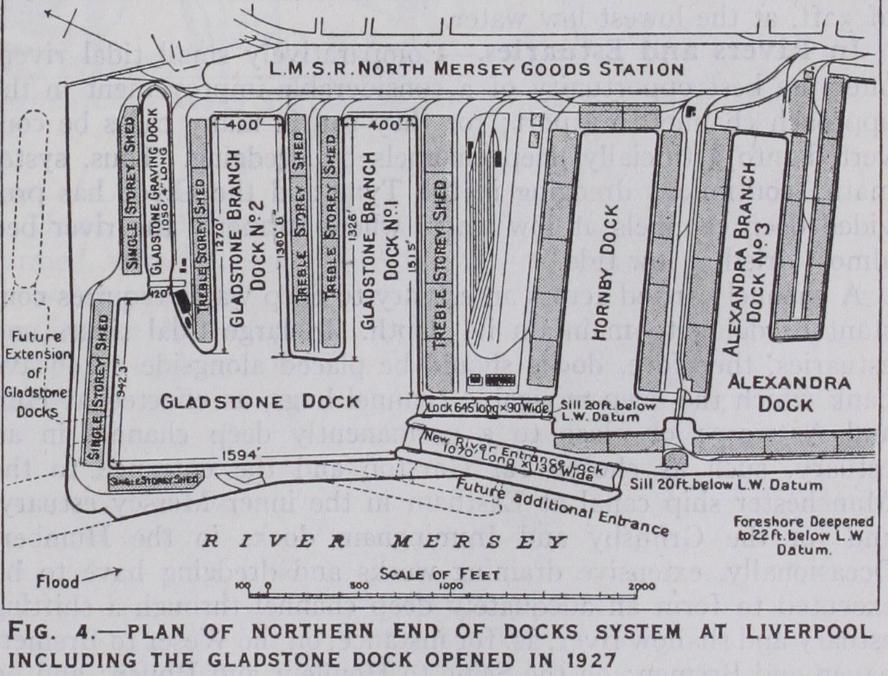

In the Mersey, with a rise of 3 f t. at equinoctial spring tides, the deep channel between Liverpool and Birkenhead and into the outer estuary of the river in Liverpool bay is main tained by the powerful tidal scour resulting from the filling and emptying of the large inner estuary. Access to the river has been rendered possible, at any state of the tide (except in the case of the largest vessels at and near low water) by dredging a channel through the Mersey bar ; the minimum depth in the bar channels is about 27ft. at mean low water spring tides (see RIVER ENGI NEERING and HARBOURS) but the docks, with the exception of those communicating with the new Gladstone dock, cannot be entered by large vessels till the water has risen above half-tide level, and the gates are closed directly after high water. Vessels of light draught are, however, able to pass in and out of the older docks from about 3 hours before to 3 hours after high water by using the locks. The opening of the Gladstone dock in 1927 allows ships of moderate size to enter it and the docks with which it com municates at all states of tide through the new deep lock.A floating landing-stage, nearly half a mile in length, in front of the centre of the docks, connected with the shore by several hinged bridges and rising and falling with the tide, enables the Atlantic liners using the port to come alongside and take on board or disembark their passengers at all times except at low water of spring tides in the case of vessels of large draught. The channel alongside the part of the stage used by large vessels has a depth of 3 2 f t. at the lowest low water.

In Rivers and Estuaries.

Comparatively small tidal rivers offer the best opportunity of a considerable improvement in the approach channel to a port; for they can in many cases be con verted into artificially deep channels by dredging. Thus, syste matic, continuous dredging in the Tyne and the Clyde has pro vided deep channels at low water where formerly the river bed almost dried at low tide.A channel carried across an estuary to deep water requires con stant dredging to maintain its depth. In large tidal rivers and estuaries, therefore, docks should be placed alongside a concave bank which the deep navigable channel hugs, as effected at Hull and Antwerp; or close to a permanently deep channel in an estuary, such as chosen for Garston and the entrance to the Manchester ship canal at Eastham in the inner Mersey estuary, and for the Grimsby and Immingham docks in the Humber. Occasionally, extensive draining works and dredging have to be executed to form an adequately deep channel through a shifting estuary and shallow river, as, for instance, on the Weser to Bremer haven and Bremen; on the Seine to Honfleur and Rouen; and on the Tees to Middlesborough and Stockton (see RIVER ENGINEER ING).

Southampton.

Southampton possesses the very rare com bination of advantages of a well-sheltered and fairly deep estuary, a rise of only i 3 f t. at spring tides, a double high water, and a position at the head of Southampton Water at the confluence of two rivers ; so that, with a moderate amount of dredging and the construction of quays, with a depth of over 4oft. in front of them at low water, it is possible for vessels of the largest draught to come alongside or leave the quays at any state of the tide. This circumstance has enabled Southampton to attract many of the Atlantic steamships formerly running to Liverpool.

In Tideless Seas.

Ports on tideless seas have to be placed where deep water approaches the shore and, if possible, where there is an absence of littoral drift. The basins of such ports are always accessible for vessels of the draught they provide for, but they require most efficient protection and, unlike tidal ports, they are not able on exceptional occasions to admit a vessel of larger draught than the basins have been formed to accommodate.