Biological Aspects of Death

DEATH, BIOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF. The life cycle of individual multicellular organisms, standing relatively high in the scale of organic specialization, as for example, a fly, a bird or a man, is typically divisible into five biologically differentiated, and usually distinct, phases as follows: (a) The formation of the zygote, which is the individual, by the union of ovum and sper matozoon in the process called fertilization. The life-history of the individual, as a distinct and biological entity, begins with this event. (b) The period of development and growth, which has two sub-phases, commonly designated respectively as embryonic or foetal, and post-embryonic or post-natal. The duration of this growth phase of the life-cycle varies widely in different organisms, as from 8 to o days in the fruit fly, Drosophila, to more than 20 years in man. This phase comes normally to an end in most forms of higher animal life, and is succeeded by (c) the phase of adult stability, in which no marked changes are observable either in the direction of growth or degeneration. This phase is the "prime of life" in common parlance. Its duration in time is again widely variable. Sooner or later the individual can be observed to have passed definitely into the next phase of the life-cycle, which may be designated (d) the period of senescence. This phase is characterized by a progressive waning in the intensity of the vital processes generally, accompanied by regressive and degenerative changes in the structures of the body. The duration in time of this portion of the life-cycle again varies greatly, but ultimately, in all the more highly specialized organisms, the life of the individual, as such, comes to an end with the terminal event of the cycle (e) death. By this term is designated the cessation of all vital capacity.

The Cycle of Life.

In the cycle of individual life as out lined, the most significant phases biologically are obviously (b) growth and (d) senescence. Phases (a) and (e) (fertilization and death) are the terminal events of the important periods (b) and (d). Phase (c) is transitional between (b) and (d), and may be wholly absent, as when obvious senescent changes follow im mediately upon the cessation of obvious growth. Indeed it is doubtful if phase (c) has theoretically any place in the life-cycle at all. Perhaps in cases where a stable adult plateau in the middle of the cycle seems to exist, it merely means that the changes of growth or of senescence are proceeding at too slow a rate to be observable by the relatively crude methods available.In the case of the human species phases (b), (c), and (d) are rather definitely and precisely limited by the biological phenom ena of birth; puberty (precisely established in the female by the onset of menstruation, or menarche); the ending of the capacity to reproduce (marked in the female by the cessation of menstrua tion, or menopause) and its diminution to statistically insignifi cant proportions in the male at about the same age; and death. Pearl has shown (The Natural History of Population, 1939) that the average age at menarche, for large samples covering many dif ferent countries and peoples, is very close to 15 years, and that the average age of menopause for similarly representative samples is between 47 and 48 years. So, in round figures, human life after birth can be divided into three periods: (1 ) The pre-reproductive period of infancy and childhood, extending from birth to about 15 years of age. In this period the individual is incapable of self maintenance or support on its own unaided resources, as well as of reproduction. (2) The reproductive period, extending from about 15 to about 5o years. In this period of life the work that supports the human socio-biological structure is mainly done, as well as the reproducing that continues the species. (3) The post-reproductive period, extending from about 5o years to the end of life. In this period the old, besides being incapable of reproduction to any statistically significant degree, are in large part dependent for their support upon the work done in the mid dle (reproductive) period of life; either by themselves with a concomitant saving for old age of the products of their efforts, or by others.

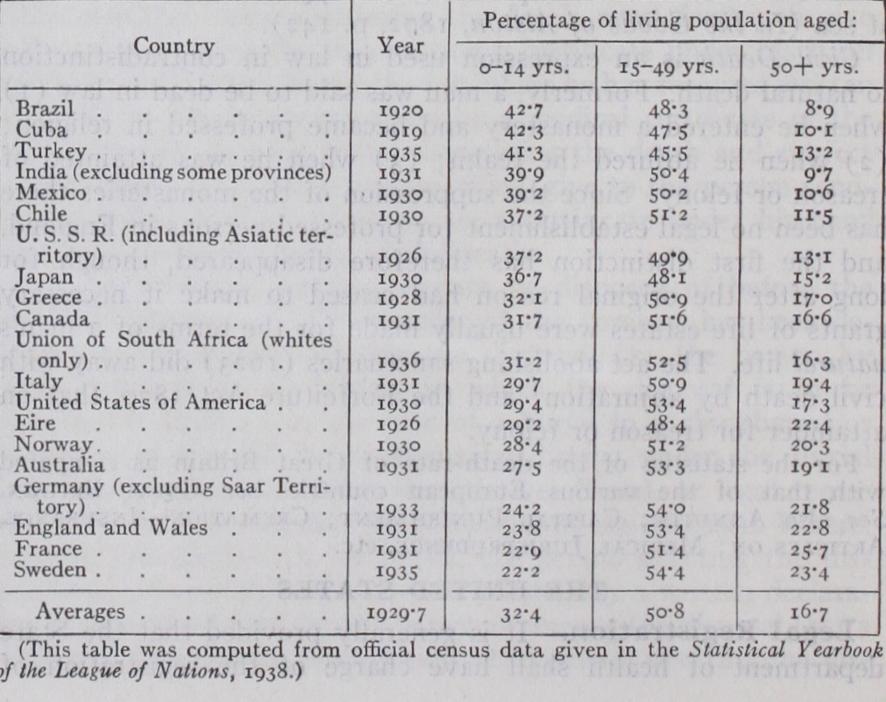

When statistics of population are arranged according to this threefold age classification a striking regularity or rule may be observed all over the world. This regularity may be stated as follows: Always and everywhere about one-half of the whole living population falls in the middle age group (15-49 years in clusive); while the other half is made up of the young (0-14 years inclusive) and the old (5o years and over) together, these two latter groups standing statistically in a compensatory relation to each other. In populations where there is a high proportion in the 0-14 year group there is a correspondingly small proportion in the so year and over group. Examples of this relationship are shown in the following table of the populations of 20 countries: From this table it is seen that countries with high rates of reproduction, and consequently relatively high proportions of their people in the 0-14 year or pre-reproductive phase (such as Brazil, Cuba, and Turkey) have but a small proportion of persons over so years of age in their populations. On the other hand countries reproducing only sparely (such as England, France, and Sweden) have a relatively high proportion of old people in the population, but only a low proportion aged o-14 years.

It has been alleged that man is unique among living things in having a disproportionately long, and from one point of view biologically useless, post-reproductive phase in the life cycle. This is not so. Other species are similar to man in this respect. Thus Pearl and Miner (Mem. Musee Roy. d'Hist. Nat. de Belgique, 2 ser., fasc. 3, 1936) showed that the females of a moth (Acrobasis carya , the pecan nut case bearer) spend an average of about 25% of their total imaginal life-span—which in chronological times lasts only 6 to 8 days on the aye' age—in the post-reproductive phase, as compared with 26% as an average for human females.

Senescence and Death.

The special problem of the biology of death is the analysis and elucidation of phases (d) and (e) of the life-cycle, senescence and death. As a result of investigations in this special field of general biology certain broad generalizations are now possible. The more important of these will now be dis cussed.

Time Duration.

The time duration of the entire individual life-cycle varies enormously, both between different forms of life, species, genera, families, etc., and also between different individuals belonging to the same species. Thus the maximum duration of life of the rotifer, Proales decipiens, is eight days (Noyes). At the other extreme there are other authentic records of individual reptiles living to as much as 175 years. Among mammals man is, on the average, the longest lived, with the ele phant as his nearest competitor for this position.

Zoological Groups.

The differences between distinct groups of animals (species, genera, families, etc.) in respect to the length of the life-span stand in no generally valid, orderly relationship to any other broad fact now known in their structure or life history. In spite of many attempts to establish such relationships every one so far suggested has been upset by well-known facts of natural history. Thus it has been contended that the duration of an animal's life is correlated with its size, in the sense that the larger the animal the longer its life. But plainly this has no general validity. Men and parrots are smaller than horses, but have life-spans of much greater length.

Individual Differences.

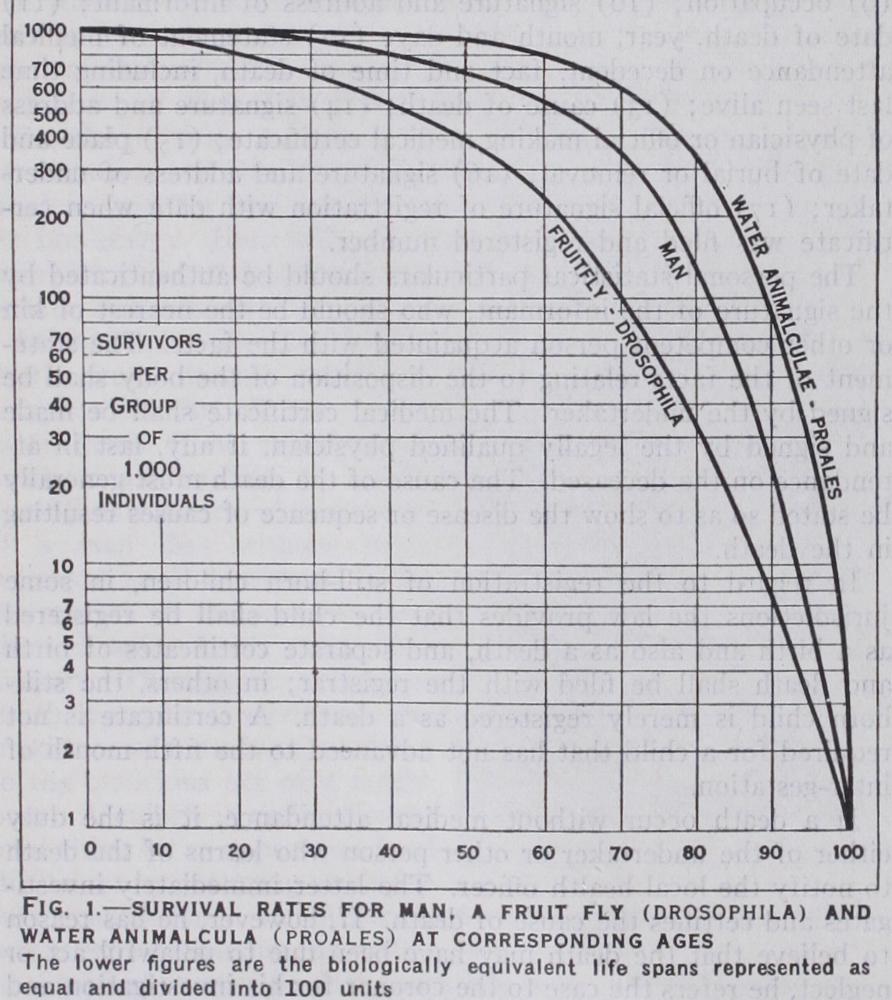

The differences between individuals of the same species in the duration of their lives are distributed in a lawful and orderly manner, in marked contrast to the appar ently haphazard character of the inter-group variation in length of life-span just discussed. The individual variation in the dur ation of life is capable of exact mathematical description, and, indeed, its treatment constitutes a special branch of mathematics, known as actuarial science. It has been shown by R. Pearl and his students that if the life of different animals, such as the rotifer, Proales, the fly, Drosophila, various other insects and man, be measured not in absolute time-units of years or days, but in terms of a relative unit, namely a hundredth part of the biologically equivalent portions of the life-span in the several cases, then the distribution of individual variation in duration of life, or the distribution of mortality in respect to age, or, in short, the life curve, is quantitatively similar in these widely different forms of life almost to the point of identity. This is illustrated in fig. 1.These facts suggest that the observed differences between in dividuals in duration of life are primarily the result of inborn differences in their biological constitutions (their structural and functional organizations) and only secondarily to a much smaller degree, the result of the environmental circumstances in which their lives are passed.

Inheritance.

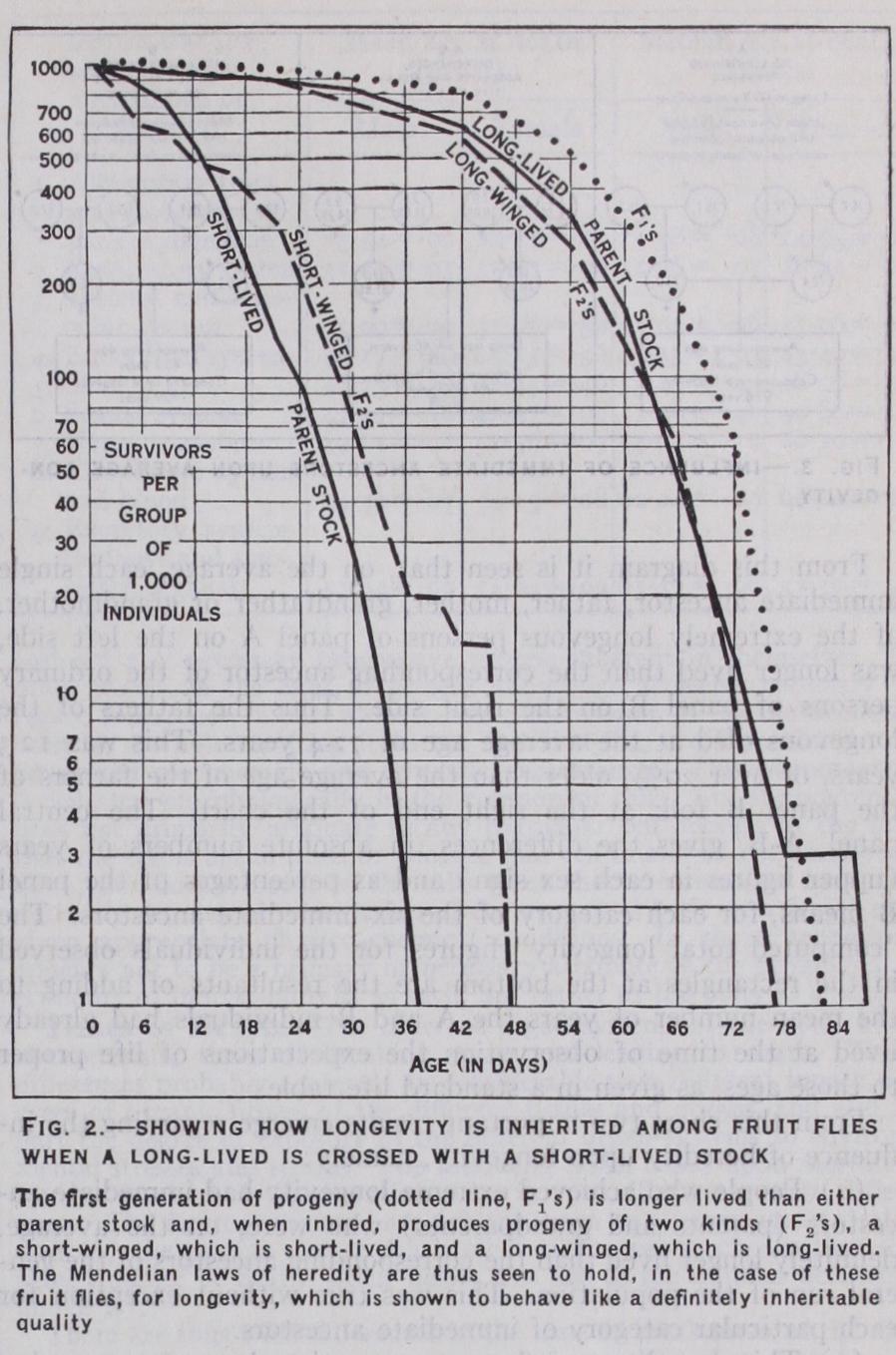

This inference is supported by the further fact that the differences between individuals which find expression in varying degrees of longevity, or duration of life, are definitely inherited. It has been proved experimentally by cross-breeding long-lived and short-lived strains of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (Hyde, Pearl and his students, Parker and Gonza lez). The results of such an experiment are shown in fig. 2.

In the first generation from such a cross the progeny ex hibit a life-curve essentially like that of the long-lived parent stock, but with a slightly greater average duration. If now these individuals are bred together inter se there are produced in the second cross-bred generation two kinds of individuals, one of which (long-winged) has a life-curve like the original long-lived parent stock, while the other (short-winged) resembles in duration of life the original short-lived parent stock. In addition to these experiments along Mendelian lines, it has been shown that there can be isolated from a general population of wild Drosophila in bred strains showing definite and permanent innate differences in average longevity. The conclusion that individual differences in life duration are fundamentally an expression of hereditary dif ferences between individuals is firmly established.

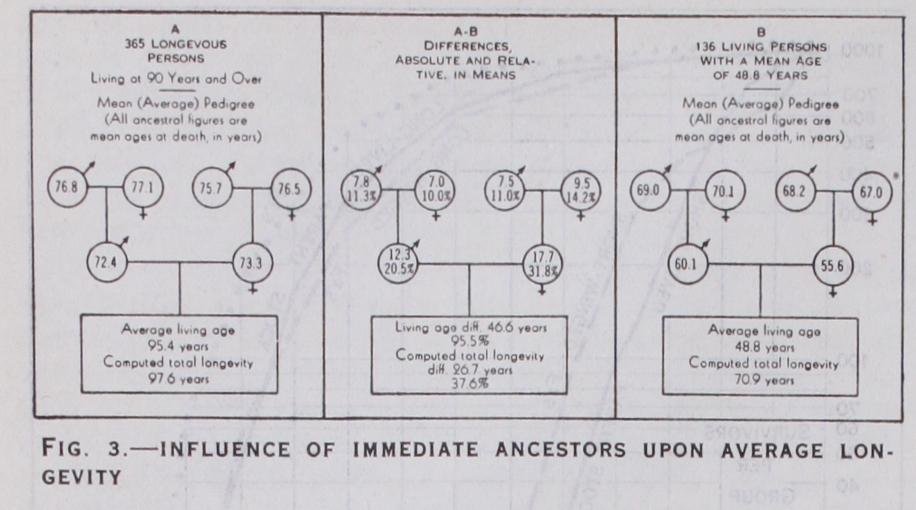

The importance of inheritance in determining human longevity has been demonstrated from various different lines of approach. In this field Karl Pearson and Alexander Graham Bell were pio neers. Pearl and Pearl studied intensively the ancestry of 365 persons living at ages of 90 and above about whose six immediate ancestors (2 parents and 4 grandparents) there was complete in formation. They compared with this group 136 persons chosen at random from the general population, all of whose 6 immediate an cestors were dead, and at known and recorded ages. This compari son group had an average living age of 48.75 years, and contained 29 persons over 6o at the time of observation, 6 over 7o, and I over 80. The average age of the group was almost 16 years higher than that of the living white population of the United States in 193o.

Fig. 3 shows how the ancestry of the nonagenarian and centen arian group compared with the group of ordinary persons in respect of average longevity.

From this diagram it is seen that, on the average, each single immediate ancestor, father, mother, grandfather or grandmother, of the extremely longevous persons of panel A on the left side, was longer lived than the corresponding ancestor of the ordinary persons of panel B on the right side. Thus the fathers of the longevous died at the average age of 72.4 years. This was 12.3 years, or over 2o%, older than the average age of the fathers of the panel B folk at the right end of the chart. The central panel, A-B, gives the differences, in absolute numbers of years (upper figures in each sex sign) and as percentages of the panel B means, for each category of the six immediate ancestors. The "computed total longevity" figures for the individuals observed in the rectangles at the bottom are the resultants of adding to the mean number of years the A and B individuals had already lived at the time of observation the expectations of life proper to those ages, as given in a standard life table.

From this chart two important results emerge regarding the in fluence of heredity upon longevity, namely: (a) People who achieved extreme longevity had immediate an cestors (parents and grandparents) who were, on the average, definitely longer lived than the corresponding ancestors of the gen eral run of the population. This was true without exception for each particular category of immediate ancestors.

(b) This hereditary influence promoting longevity was be tween two and three times as great relatively for parents as it was for grandparents.

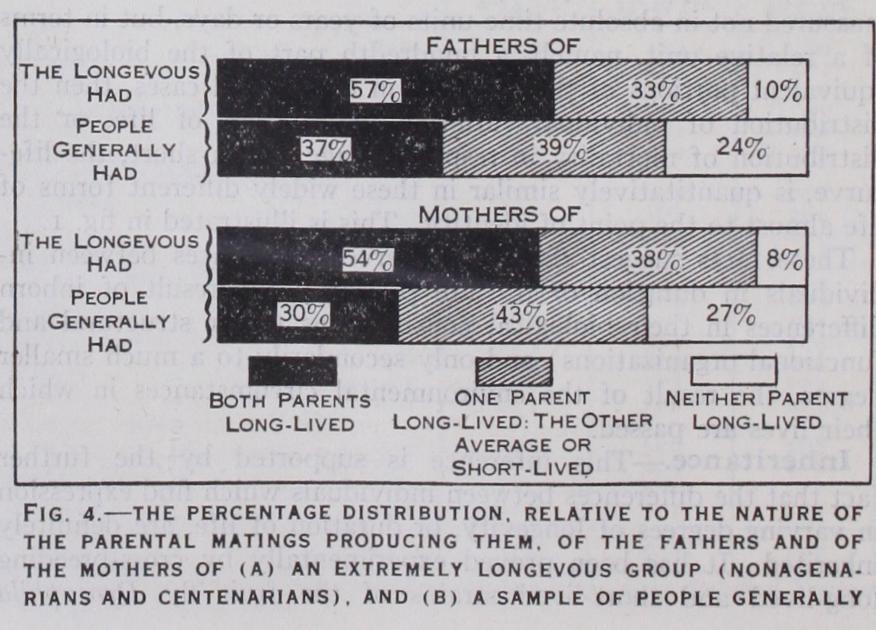

A specific study was made as to how each of the parents of the extremely longevous persons was bred relative to longevity, as compared with the parents of the general run of folk. This led to the results shown in fig. 4. In this study an individual who died under 5o years of age was regarded as short lived; one who died betv,Yeen 5o and 69 as average or mediocre in life duration, and one who died at 7o or over as long lived. Fig. 4 shows the percentages of the fathers and mothers respectively that had (a) both of their parents long lived (shown by the solid black por tion of each bar); (b) one parent long lived and the other med iocre or short lived (shown by the cross-hatched portion of each bar) ; and (c) neither of their parcnts long lived (shown by the white portion of each bar).

The picture presented by fig. 4 is precise and striking. The nonagenarians and centenarians were produced by parents who were themselves bred out of wholly longevous parentage in more than half of all the cases observed—a markedly higher proportion than that shown by the parents of the general population sample. At the other end of the genetic scale the opposite is true. Fewer than half as many proportionally of the nonagenarians and cen tenarians as of persons generally were produced by parents who themselves had no longevous parentage whatever. There can be no question or doubt that breeding was of great importance in the production of these nonagenarians and centenarians.

Actuarial studies have also demonstrated the importance of heredity in the achievement of long life. This fact has been equally established by life tables for parents of children who died at specified ages, and by life tables of children of parents having specified degrees of longevity. For example such studies have shown that the mean-after-lifetime of fathers of children dying (or living) at ages of 8o and over is about 26% greater at age 20; 43% greater at age 4o, 75% greater at age 6o; and 58% greater at age 8o, than the mean-after-lifetime at the same ages of fathers of children dying under 5. The corresponding excesses in.expectation of life of mothers were 27% at age 20; 27% at age 4o; 36% at age 6o; and 23% at age 80. Throughout the whole life-span the parents of the very long-lived children appear to be persons of superior biological constitution, as evidenced by their ability to keep on living.

Similar studies have shown that the sons of fathers dying (or living) at ages of 8o years and over have a mean-after-lifetime about 13% greater at birth than that of the sons of fathers dying between 5o and 79 years of age, and 22% greater than that of sons of fathers dying under so years of age.

Further evidence for the innate constitutional superiority of the longevous was afforded by Pearl's and Raenkham's (Human Biology, vol. 4, 1932) analysis of the causes of death of nonagen arians on the basis of the official records of the Census Bureau. That analysis led to the conclusion that nonagenarians are a selected lot of people. They are the ultimate survivors after all the rest of mankind has gone, unable to meet the vicissitudes of life and keep on living. Nonagenarians and centenarians come to be such because they have organically superior constitutions, re sistant to infections, soundly organized to function efficiently as a whole organism and keep on doing it for a very long time. Observations on mortality at ages have indicated that throughout life infections and other harmful environmental forces were, on the whole, tending to take off the weaker and leave the stronger. Medical knowledge and skill, improved sanitation and better con ditions of life generally have been able to prevent an increas ingly larger amount of premature mortality before age 5o. Especially have these agencies been able to reduce the lethal effects of infections, or at least to postpone to a later part of the life-span their fatal action. But ultimately there is left a group of extremely old people, for whom on the whole in fections have no particular terrors. In all the early part of their lives they have been able successfully to resist infections, and to a remarkable degree still are in extreme old age. These people eventually die. But a great many of them die, not be cause the noxious forces of the environment kill them, but because their vital machinery literally breaks down, and particularly that important part of it—the circulatory system.

Natural Death a Novelty.—Neither senescence nor natural death is a necessary, inevitable consequence or attribute of life. Natural death is biologically a relatively new thing, which made its appearance only after living organisms had advanced a long way on the path of evolution. The evidence supporting this con clusion is manifold, and may be considered under several heads. (a) Various single-celled organisms (Protozoa, q.v.) prove, under critical experimental observation, to be, in a certain sense, im mortal. They reproduce by simple fission of the body, one in dividual becoming two, and leaving behind in the process nothing corresponding to a corpse. The brilliant work of Woodruff and his students, in particular, has demonstrated that this process may go on indefinitely, without any permanent slacking of the rate of cell-division corresponding to senescence, and without the inter vention of a rejuvenating process such as conjugation or en domixis, providing the environment of the cells is kept favourable. (b) The germ cells of all sexually differentiated organisms are, in a similar sense, immortal. Reduced to a formula we may say that the fertilized ovum (united germ cells) produces a soma and more germ cells. The soma eventually dies. Some of the germ cells prior to that event produce somata and germ cells, and so on in a continuous cycle which has never yet ended since the appear ance of multicellular organisms on the earth. (c) In some of the most lowly-organized groups of many-celled animals or Metazoa, the power of multiplication by simple fission, or budding off of a portion of the body which reproduces the whole, is retained. or agamic, mode of reproduction occurs as the usual, but not exclusive, method in the three lowest groups of multi cellular animals, the sponges, flatworms and coelenterates. More rarely it may occur in other of the lower invertebrates.

So long as reproduction goes on in this way in these multicellular forms there is no place for death. In the passage from one gener ation to the next no residue is left behind. Agamic reproduction and its associated absence of death also occur commonly in plants. Budding and propagation by cuttings are the usual forms in which it is seen. The somatic cells have the capacity of continuing multiplication and life for an indefinite duration of time, so long as they are not accidentally caught in the breakdown and death of the whole individual in which they are at the moment located.

(d) There is some evidence that in certain fish there is no occurrence of senility or natural death, but that instead the animal keeps on growing indefinitely, and would be immortal except for accidental death. The animal soma in such cases behaves like the root stock of a perennial plant. (For further discussion of this line of evidence see interesting correspondence by Geo. P. Bidder, in Nature, vol. cxv., 1925, passim and M. A. C. Hinton's monograph of the Voles and Lem mings [British Museum, 1926], in which it is concluded that voles of the genus Arvicola "are animals that never stop growing and never grow old.") (e) The successful cultivation in vitro of the tissues of higher vertebrates, even including man himself, over an indefinitely long period of time, demonstrates that senescence and natural death are in no sense necessary concomitants of cellular life. Carrel and Ebeling, by transferring the culture at frequent intervals into fresh nutrient medium, have kept alive and in perfectly normal and healthy condition, a culture of tissue (see TISSUE CULTURE) from the heart of a chick embryo for more than 25 years; i.e., for much longer than the normal life-span of the fowl. There is every reason to suppose that, by the continuation of the same technique, the culture can be kept alive indefinitely. The experimental culture of cells and tissues in vitro has now covered practically all of the essential tissue elements of the metazoan body, even including some of the most highly differentiated of those tissues. Nerve cells, muscle cells, heart muscle cells, spleen cells, connective tissue cells, epithelial cells from various locations in the body, kidney cells and others have all been successfully cultivated in vitro.

Potential may fairly be said that the potential immortality of all essential cellular elements of the body either has been fully demonstrated, or has been carried far enough to make the probability very great, that properly conducted experiments would demonstrate the continuance of the life of these cells in culture to any indefinite extent. It is not to be expected, of course, that such tissues as hair or nails would be capable of independent life, but these are essentially unimportant tissues in the animal economy, as compared with those of the heart, the nervous system, the kidneys, etc. General izing from results of tissue culture work of the last three decades, it is highly probable that all the essential tissues of the metazoan body are potentially immortal, when placed separately under such conditions as to supply appropriate food in the right amount, and to remove promptly the deleterious products of metabolism.

Death Among Multicellular fundamental rea son why the higher multicellular animals do not live forever appears to be that in the differentiation and specialization of function of cells and tissues in the body as a whole, any individual part does not find the conditions necessary for its continued existence. In the body any part is dependent for the necessities of its existence, as for example nutritive material, upon other parts, or put in another way, upon the organization of the body as a whole. It is the differentiation and specialization of function of the mutually dependent aggregate of cells and tissues which constitute the metazoan body that brings about death, and not any inherent or inevitable mortal process in the in dividual cells themselves.

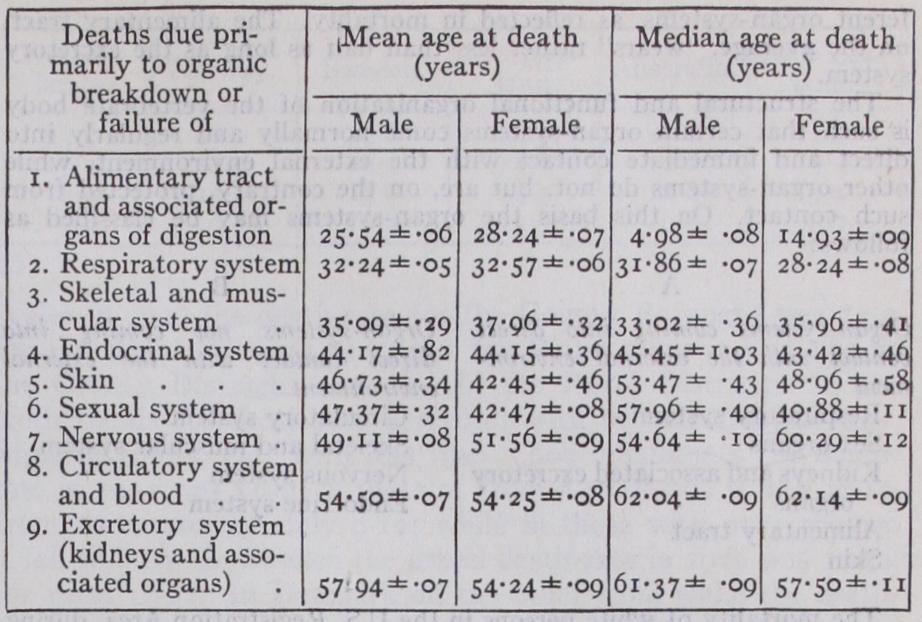

When cells show characteristic senescent changes it is perhaps be cause they are reflecting, in their morphology and physiology, a conse quence of their mutually dependent association in the body as a whole, and not any necessary progressive process inherent in themselves. In other words, in the light of present knowledge, it seems necessary to regard senescence, in part at least, as a phenomenon of the multicellular body as a whole resulting from the fact that it is a differentiated and integrated morphologic and dynamic organization. This phenomenon is reflected morphologically in the component cells. But it apparently does not primarily originate in any particular cell because of the fact that the cell is old in time, or because that cell in and of itself has been alive; nor does it occur in the cells when they are removed from the mutually dependent relationship of the organized body as a whole and given appropriate physicochemical conditions. In short, senescence appears not to be a primary or necessary attribute to the physiological economy of individual cells as such, but rather of the body as a whole. Times of different organ-systems of the body have characteristic times of breaking down and leading to death. These differences probably represent in considerable part different innate de grees of organic fitness of the different tissues and organs, and also in part the degree of exposure of the different organ-systems to environ mental stresses and strains. The following table, based upon mortality returns of the U.S. Registration Area in 191o, illustrates these differ ences. The figures tabulated are (a) the mean or average age at death, and (b) the median age at death (that is, the age so chosen that the same number of deaths occur below this age as the number occurring above it) .

There are thus wide differences in the time of breakdown of the dif

ferent organ-systems, as reflected in mortality. The alimentary tract, on the average, "wears" rather less than half as long as the excretory system.

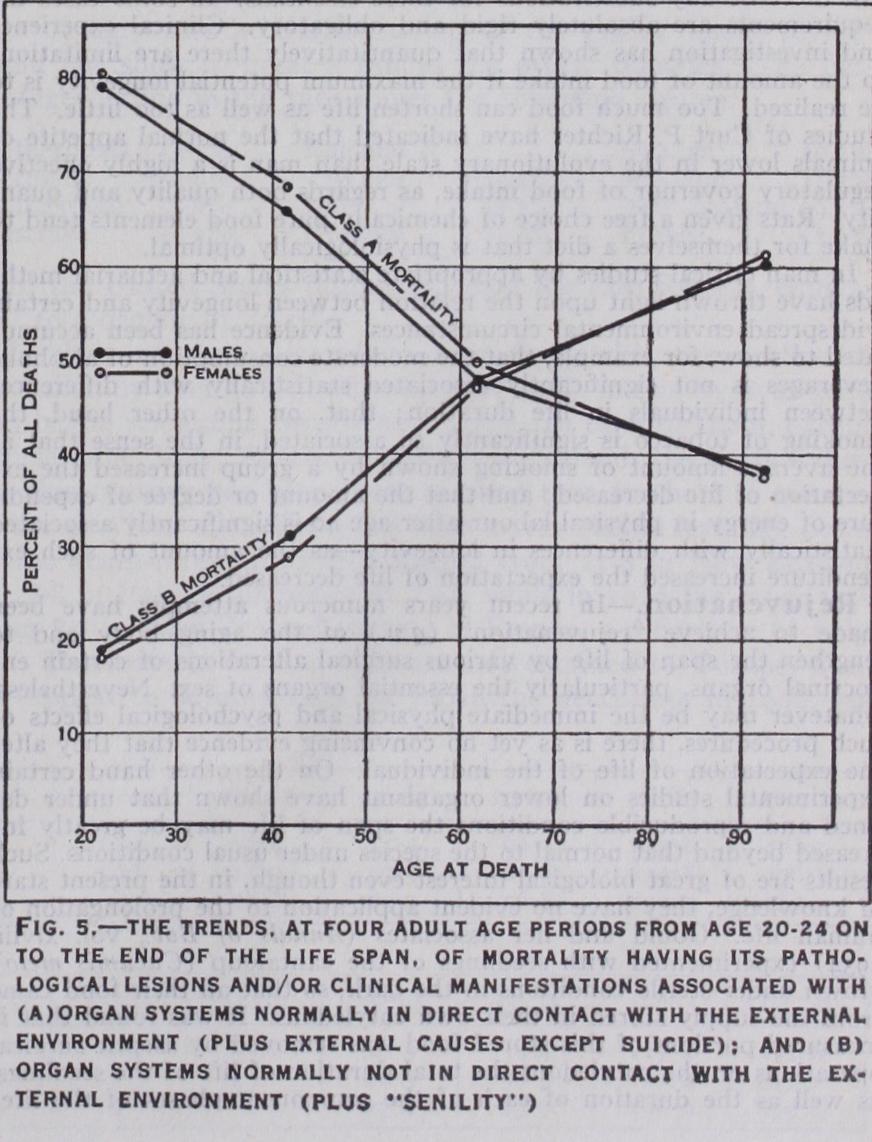

The structural and functional organization of the vertebrate body is such that certain organ-systems come normally and regularly into direct and immediate contact with the external environment, while other organ-systems do not, but are, on the contrary, protected from such contact. On this basis the organ-systems may be classified as follows: The mortality of white persons in the U.S. Registration Area, during the five-year period 1923-27 inclusive has been subsumed under this A (unprotected) and B (protected) classification of organ-systems by Pearl and Raenkham, with the results shown in fig. 5.

It is seen from this diagram that, with advancing adult age the pro portion of deaths due to causes having their pathological lesions or clinical manifestations associated with the organ-systems of the body which are normally and regularly in direct contact with the external environment (Class A mortality) decreased, while the proportion hav ing their pathological lesions or clinical manifestations associated with the organ-systems normally protected from direct contact with the external environment (Class B mortality) increased.

Death and the

is a plain fact of experience that the environmental circumstances surrounding an organism may, in varying degrees, condition its duration of life. Thus complete star vation can induce death in a much shorter time than would have oc curred in the absence of starvation. Similarly, there are many poisons that are lethal in appropriate doses. But, quite apart from such ex treme and violent agents, the effect upon longevity of the never-ceasing changes in the normal environment is a matter of the first importance in reaching an understanding of the biology of death. The vast litera ture embodying the results of modern studies on nutrition and diet has shown, directly and indirectly, the role played by this factor in influ encing life duration. Research in the field of nutrition has shown that qualitatively the diet of each particular kind of living organism must contain certain chemical elements and compounds in adequate amounts and proportions if life is to continue. Only within very narrow limits can there be any substitutions for these essentials. In some cases the requirements are absolutely rigid and obligatory. Clinical experience and investigation has shown that quantitatively there are limitations to the amount of food intake if the maximum potential longevity is to be realized. Too much food can shorten life as well as too little. The studies of Curt P. Richter have indicated that the normal appetite of animals lower in the evolutionary scale than man is a highly effective regulatory governor of food intake, as regards both quality and quan tity. Rats given a free choice of chemically pure food elements tend to make for themselves a diet that is physiologically optimal.In man critical studies by appropriate statistical and actuarial meth ods have thrown light upon the relation between longevity and certain widespread environmental circumstances. Evidence has been accumu lated to show, for example, that the moderate consumption of alcoholic beverages is not significantly associated statistically with differences between individuals in life duration ; that, on the other hand, the smoking of tobacco is significantly so associated, in the sense that as the average amount of smoking shown by a group increased the ex pectation of life decreased; and that the amount or degree of expendi ture of energy in physical labour after age 4o is significantly associated statistically with differences in longevity—as the amount of such ex penditure increased the expectation of life decreased.

recent years numerous attempts have been made to achieve "rejuvenation" (q.v.) of the aging body and to lengthen the span of life by various surgical alterations of certain en docrinal organs, particularly the essential organs of sex. Nevertheless, whatever may be the immediate physical and psychological effects of such procedures, there is as yet no convincing evidence that they alter the expectation of life of the individual. On the other hand certain experimental studies on lower organisms have shown that under de fined and reproducible conditions the span of life may be greatly in creased beyond that normal to the species under usual conditions. Such results are of great biological interest even though, in the present state of knowledge, they have no evident application to the prolongation of human life. Gould and her associates (Annals of Bot., vol. xlviii, 1934) experimented with seedlings of the cantaloup (Cucumis melo) grown under sterile conditions in the dark, so that all their food came from the supply stored in their own cotyledons. It was found that if measured portions of this stored food was removed by aseptic surgical operations on the cotyledons the total duration of life of the seedlings, as well as the duration of each of the component phases of the life cycle, could be prolonged up to as much as o to 7 times the normal ex pectation for the amount of food available. Furthermore the amount of growth, however measured, was increased as compared with the normal for the same amount of available food. Other experimental studies on various lower animals have shown that partial starvation materially increased the duration of life.

theories of senescence have been advanced. No one of them can be regarded as entirely satisfactory, or as generally established by the evidence. Most of them suffer from the logical de fect of setting up some particular observed attribute or element of the phenomenon of senescence itself, such as protoplasmic hysteresis, slow ing rate of metabolism (meaning essentially only reduced activity), etc., as the cause of the whole. More experimental work on the prob lem is essential ; in particular in the direction of producing at will, and under control, the objective phenomenon of senility irrespective of the age of the organism, and conversely preventing the appearance of these phenomena in old animals.