Bonization

BONIZATION.) Finally, there is sublimation, in which a solid distils to give a solid without the intervention of a liquid phase.

Historical Note.—Distillation appears to have been used by the earliest experimentalists. Aristotle (384-322 B.c.) mentions that pure water is made by the evaporation of sea-water. Pliny the elder (A.D. 23-79) describes a primitive method of condensa tion, in which the oil obtained by heating rosin is collected on wool placed in the upper part of the still. The Alexandrians added a head or cover to the still, and prepared oil of turpentine by dis tilling pine resin.

The Arabians improved the apparatus by cooling the tube lead ing from the head, or alembic, with water, and discovered a num ber of essential oils by distilling plants and plant juices, alcohols from wine, and distilled water. By its use, the alchemists were enabled to study hydrochloric, nitric and sulphuric acids in a rela tively pure state.

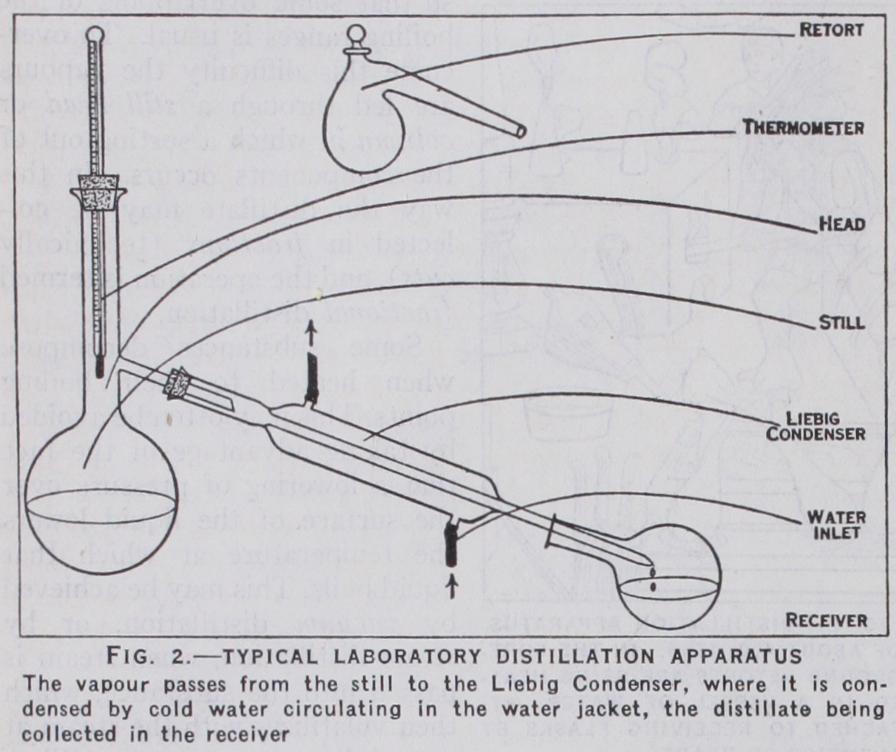

Modern laboratory practice owes much to the introduction, since 185o, of the condenser named after Liebig (fig. 2), and of the re flux condenser by Kolbe and Frankland. The latter is a con denser arranged vertically so that the condensed vapours return continually to the distilling vessel, and allows of the continued boiling of a liquid without loss. Dittmar and Anschiitz introduced, independently, reduced pressure distillation, and fractional distil lation was aided by the advent of the still-heads of Wurtz Linnemann (1871), and le Bel and Henninger (18 i4).

Distillation will now be dealt with in more detail under the headings :—(1) simple distillation, (2) fractional distillation, (3) reduced-pressure distillation, (4) high-vacuum distillation, (5) steam distillation, (6) dry distillation, (7) theory of distillation, (8) distillation in technology, and (9) distillation of water.

(I)

Simple Distillation.—Retorts are now rarely used. Lab oratory distillation in its simplest form is carried out in the appa ratus depicted in fig. 2.The diagram is self-explanatory, but it may be remarked that laboratory ware is usually constructed in glass, and connected together by means of corks or rubber bungs. When the materials to be distilled are corrosive to cork or rubber, the distilling flask, condenser and receiver are connected by ground-glass joints, or they may be fused together with the blow-pipe, thus giving an all-glass apparatus. Heating of the distilling flask is effected in a variety of ways depending upon the volatility and inflammability of the substance to be distilled. It may be by direct gas flame, or indirectly through a sand-tray or wire gauze, by electric hot plate, by internal heating of the liquid by platinum wire, or by immersion in a steam, oil or fusible metal bath. Some liquids boil explosively when heated'and the phenomenon is known as bumping. This may be prevented by placing small pieces of porcelain, pumice, capillary tubing or other porous material in the still. In distilling substances likely to decompose when heated in air, an inert gas is led through the apparatus during the operation.

It will be seen from figs. and 2 that the modern still is simi lar in principle to that of the alchemists, but a thermometer is added to facilitate control of the process. This is usually placed so that its bulb is near the point at which vapour leaves the still. Consequently a part of the mercury in the thermometer may be at a lower temperature than that in the bulb. To obtain the true temperature a correction for "exposed stem" is applied to the observed reading.

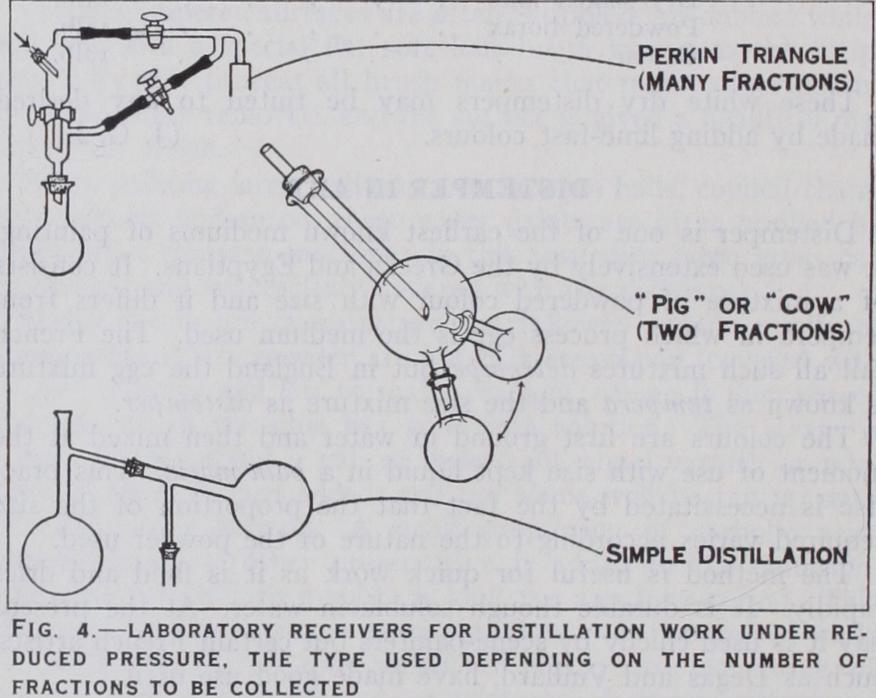

The choice of condenser in any given case is governed by the volatility of the substance to be distilled. With substances boiling above 17o° C, air cooling of an elongated side tube is generally sufficient, but for ordinary work the Liebig single surface con denser (fig. 2) is used. For very volatile organic liquids the double surface (fig. 3) is necessary. Numerous types are avail able, but the difference lies mainly in the ingenuity with which the internal members are designed to give the maximum cooling surface. The spira/ or worm condenser is a compact f orm of the Liebig, an example being the British Inland Revenue pattern.

(2) Fractional Distillation.

Fractional distillation implies the separation of mixtures. of substances of different boiling point. The nearer these boiling points are to one another, the more diffi cult is the operation. It is facilitated by elongation of the distilling flask neck, or by adding what is known as a fractionating column.Numerous columns have been devised, but all work on the principle of allowing the more volatile portion of the vapour to proceed to the condenser whilst returning the less volatile to the still. Of the three main types, the plain column, of which the Wurtz bulb and the Young pear columns are modifications, is the least efficient. The second class of column is maintained at the temperature at which the most volatile constituent of the vapour distils. The third type, better known as the dephlegmator type, is the most widely used. In this the ascending vapours from the still bubble through portions of the already condensed vapour. The Linnemann modification passes the vapour through condensate temporarily collected on platinum gauzes at constrictions in the column. The le Bel–Henninger embodies a further development of the idea, and successive bulbs are connected by syphons (fig. 3). The Young rod and disc, the Hempel glass bead, the Raschig and the Lessing rings and the Young evaporator columns are all exten sions of the same principle. Duf ton 0919) has devised a very simple column which consists of a wire wound spirally in the an nular space between a closed centre member and the outer column body. It is simple to construct, efficient in operation and is essen tially a laboratory adaptation of the commercial column due to Foucar.

(3) Reduced-pressure Distillation.

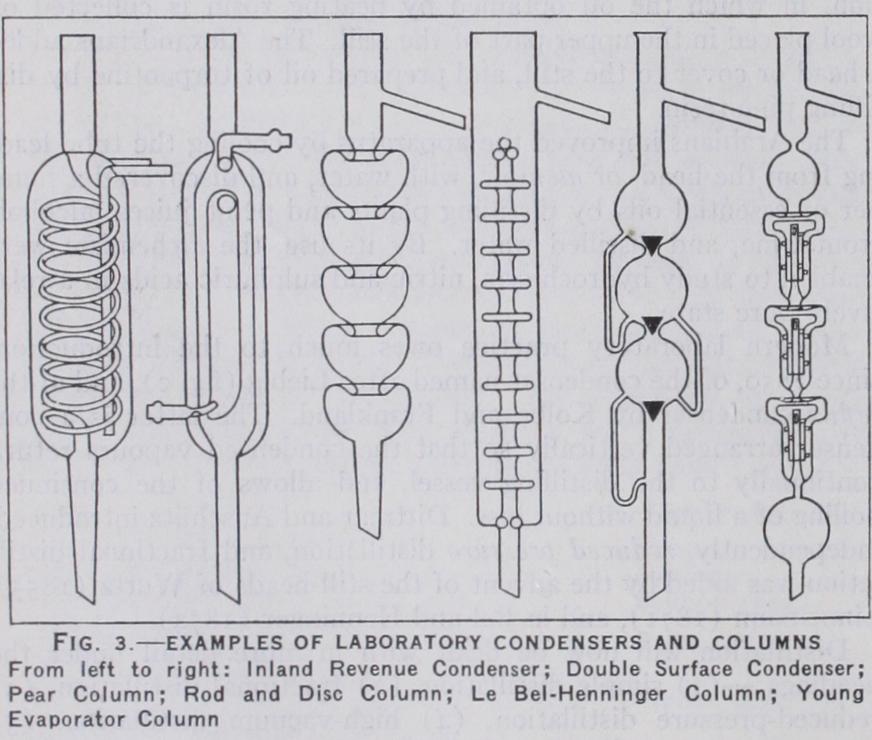

Distillation under re duced pressure is adopted when dealing with substances which normally boil at inconveniently high temperatures, or with decom position under atmospheric pressure. The. apparatus used differs but little from that already described. The receiver is connected by thick-walled rubber tubing to a manometer, for determining pressure, and to some form of vacuum pump. To avoid bumping the usual method is to introduce a fine stream of gas bubbles through the liquid by means of a capillary tube reaching to the bottom of the still. A very common form of apparatus for this work is the Claisen flask, which has two necks, one holding the capillary tube, and the second the thermometer.

If it is required to collect fractions under reduced pressure, some special form of receiver is necessary. A Bredt pig (fig. 4) is used for two or three fractions, the Perkin triangle is useful for a series of fractions where the distillate is fairly mobile, whilst the Briihl apparatus is most suitable for the distillation of solids, as fatty acids or waxes.

(4) High-vacuum Distillation.

Whereas reduced pressure distillation implies distillation at pressures of 5-15 mm. of mer cury, it is an advantage for some purposes to go much lower, from i mm. down to X-ray vacuum conditions. Krafft used a cathode vacuum for distilling paraffin waxes, and to-day high vacuum distillation is being used for purification of various gland extracts for medicinal purposes. Ordinarily, a typical high vacuum distillation' set, embodies a distillation flask with Wurtz head, which may be further improved by the insertion of a Dufton column. The distillate is delivered into a Briihl multiple receiver having special glands to stand up to extreme vacuum conditions. The vacuum in this case is maintained by a Kaye annular-jet mercury vapour pump, backed by a Cenco Hyvac rotary oil pump. Such an apparatus is capable of maintaining a working vacuum of o.000i mm. of mercury at the receiver when distilling paraffin waxes.(5) Steam Distillation.—In this operation steam, generated as a rule but not invariably in separate apparatus, is passed into the still, and the resulting mixed vapours are condensed in the usual manner. The process is equivalent to reduced pressure dis tillation, for Dalton's "Law of Partial Pressures" is applicable, and the substance distilled with steam only attains the temperature corresponding to its partial pressure. Thus benzaldehyde, which boils at 178.3° C at 76o mm., distils with steam at 97.9° C, cor responding to its partial pressure of 56.5 millimetres. This is, in effect, a reduction in pressure of 703.5 millimetres. Familiar in stances of the use of this method are the separations of ortho and para-nitrophenols, and of aniline and nitrobenzene, of which the first in each pair is volatile in steam. Liquids other than water can be used in analogous operations. Alcohol is used to remove phenol from the condensation product of phenol and formalde hyde. (See RESINS, SYNTHETIC.) (6) Destructive and Dry Distillation.—These processes refer to operations on solid materials. The dry distillation of calcium acetate gives acetone. The destructive distillation of wood gives acetone, acetic acid and methyl alcohol; and of coal, coal gas, benzene and a multitude of other chemical products. Dry distillation is best carried out in shallow stills with small batches of material. Caking may be partially prevented by mixing the charge with sand or pumice.

(7) Theory of Distillation.—The general observation that under constant pressure a pure substance boils at constant tem perature leads to the conclusion that the distillate which comes over while the thermometer records only a small variation is of practically constant composition. On this depends all rectification or separation by distillation. The theory of distillation is com plex, and we shall confine ourselves to mixtures of two compo nents, A and B, of which three cases are to be recognized, accord ing as the two are: (I) quite insoluble in each other, (2) miscible only within limits, and (3) miscible in all proportions.

When the components are completely immiscible the vapour pressure of one is not influenced by the other, and the mixture distils at the temperature at which the sum of the partial pressures equals that of the atmosphere. Both components distil in con stant proportion until one disappears, when the residue distils if the temperature is raised. The composition of the distillate is determinate if the molecular weights of the components and the vapour pressures at the temperature of distillation are known. It is not proposed to enter into this in detail, but it may be noted that in steam distillation the low volatility of a substance may be off-set by its high molecular weight.

When distilling a mixture of partly miscible components a distillate of constant composition is obtained so long as two layers are present ; i.e., A dissolved in B and B in A, since, in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics, these solutions emit vapours of the same composition. The composition of the vapour is not, however, the same as that of either layer. As the distilla tion proceeds one layer diminishes more rapidly than the other until one remains, which then distils as a completely miscible mixture.

The distillation of completely miscible mixtures is the most common practically, and the most complex theoretically. Such mixtures are of three kinds, depending upon the relative solu bilities of the vapours in the liquids.

(i.) If the vapour of A is readily soluble in the liquid B, and the vapour of B in A, there will exist a mixture of A and B having a lower vapour pressure than any other mixture. The vapour pressure-composition curve is convex to the axis of com position, the maximum vapour pressures corresponding to pure A and B, and the minimum to some mixture of A and B. On distilling such a mixture two components, in varying amounts, come over until the still contains the mixture of minimum vapour pressure, which then distils at constant temperature. Nitric acid of boiling point 86° C, forms a mixture with water, boiling point C, which boils at a constant temperature of 1 20.5 ° C, and contains 68% of acid.

(ii.) If the vapours are sparingly soluble in the liquids, there will exist a mixture having a maximum vapour pressure. The vapour pressure-composition curve is concave, the minima corre sponding to the pure components. On distilling this mixture a mixed vapour of constant composition distils, leaving one or other of the components. Propyl alcohol and water furnish an example.

(iii.) If the vapour of A is readily soluble in B, and the vapour of B sparingly so in A, and if the vapour pressure of A is greater than that of B, then the vapour pressure of mixtures of A and B approximates to a linear function of the composition. On distilling this mixture, pure A comes over first, followed by mixtures in which the quantity of B continually increases. As a consequence A and B can be completely separated by a sufficient number of distillations. As an example we have methyl alcohol and water.

These five cases have been illustrated in one diagram by van't Hoff. In fig. 5, AB is the axis of composition, AP the vapour pressure of A, BQ of B. For immiscible liquids the vapour pressure curve is the horizontal line ab, where aP = QB, and bQ = AP. For partially miscible liquids the curve is The horizontal line corresponds to the two layers of liquid, and the inclined lines to the tions of B in A and A in B. The curves having a minimum at with a maximum at and the straight line correspond to the types (i.), (ii.) and (iii.), of the completely miscible mixtures.

(8) Distillation in Technology.—Distillation in all its forms is used in chemical technology. The type of apparatus in any par ticular process is conditioned by various factors, such as the nature of the original mixture and the available means of heat ing. The simplest still consists of a closed cylinder of cast or wrought iron, provided with a tubular neck. If horizontal, the ends are usually convex, but if vertical, the base may be either concave or convex. The convex bottom has the advantage of increased heating area and ease of cleaning, but the disadvantage that the run-off is at the point of maximum heat. In the concave type the run-off comes at the edge, but the still is difficult to clean. Tar stills are often of the vertical type, whilst horizontal ones are popular in the petroleum industry. Pipe stills in which the charge is pumped continuously through a heated coil are used to some extent.

A complete still is provided with a hemispherical head, and, in addition to the large opening to carry away vapours, may be fitted with : (I) bearings for stirring gear, (2) pressure or vacuum gauge, (3) inlet and outlet for closed steam coil, (4) a tube reaching to the bottom of the still to introduce live steam, (5) closed tubes to carry thermometers, (6) man holes for charging, (7) inspection windows, and (8) a safety valve. Such stills are made in a large variety of materials—cast and wrought iron, copper, mild steel, nickel and aluminium are common. Lead-lined stills are used, and for food products or fine chemicals enamelled or even glass-lined stills are particularly useful. Fused silica is used for nitric acid distillation, and glass and stoneware for bromine and iodine.

Stills may be heated by solid combustible, as coal, coke or an thracite, or gas fired. Steam may be used either as open steam, actual steam distillation, or closed, in which steam is the heating medium only. Indirect heating has the advantage over direct firing that there is no tendency to local overheating or burning, and it is subject to closer control. Steam-heated stills can be regu lated by ingenious devices which automatically ensure that the concentration of the distillate is unaffected by change in steam pressure.

Mention should here be made of an important modern develop ment in distillation technique. In the T.I.C. method of tar dis tillation molten lead is commonly used as the medium for the transfer of heat from the furnace to the actual charge. A con tinuous stream of tar is introduced on to the surface of molten lead in a labyrinth shaped like an Archimedian spiral. The method has the important advantage that any coke or pitch formed is read ily removed from the surface of the lead, and the process becomes perfectly continuous. Since only a small amount of tar is in the still at any one time the plant is particularly flexible.

In commercial practice three main types of column are used, the packed column, based on the laboratory Hempel, the perforated plate, and the bubbler hood or bell columns. In recent types of packed column special fillings are used, such as those of Raschig, Lessing, Goodwin and Prym. The Raschig filling consists of open cylinders of any suitable material, varying in size according to the operation. In plate columns, the fractionating effect is obtained by bubbling the vapour through films of liquid on perforated plates. Since efficiency depends upon the relation between the rate of evaporation and the size of hole, the apparatus is not very flexible. The bubbler hood or bell type column is extensively used in the rectification of alcohol. In these columns condensed liquid is maintained at constant level in each section, and the ascending vapour forced, as streams of fine bubbles, through the liquid by means of slotted bells placed over the up-going vapour tubes.

Of condensers, the worm, tubular and open surface may be mentioned. An example of the popular worm type is shown with out water jacket in Plate II. In the tubular condenser a counter current effect is obtained and the cooling water flows rapidly past the vapour tubes, whilst in the open surface type, the vapour passes through a bank of tubes cooled by trickling water and is thus condensed.

There is one important operation, primarily of distillation, where the product left in the still is the first consideration. This is known as evaporation, and may be applied to operations as various as those for obtaining salts from sea water, to concentra tion of milk or tomato juice to give edible products.

(9) Distillation of Water.

Water free from dissolved gases and salts is indispensable in many scientific and industrial opera tions. The laboratory still for the purpose is very simple. The boiler, fed by warm water from the condenser, is usually of cop per, and the head and worm of copper or tin.The problem of the economic production of potable water from sea water is very old. In 1683, Fitzgerald patented a process for "the sweetening of sea water." Hales (1739) gives a history of the earlier attempts in his book, Philosophical Experiments.

Early forms of the modern apparatus were invented by Chaplin of Glasgow, Rocher of Nantes, and by Galle and Mazeline of Havre. The Normandy apparatus was effective and economical, and extensively used in the British navy, but owing to its expen sive and complicated structure it has largely given place to the Weir type of plant (fig. 6).

The modern plant consists of three main parts, the evaporator, distiller and condenser. In some types of condenser the tubes are of oval section, as in the German Pape-Henneberg, or crescent shaped as in the Quiggins. Royles' plant uses the Row patent tube consisting of tubes indented alternately at right angles. An important feature of such tubes is that they are self-scaling in use. In distilling plant for ship-board use compactness is the first essen tial, whilst for terrestrial work the more elaborate form of appa ratus such as the Mirlees-Watson sextuple effect evaporator (Plate V.) gives strikingly economical results.