Caissons Dock Gates

DOCK GATES, CAISSONS, ETC.

Sluice Valves, etc.

Valves or sluice gates in various forms are used f or controlling the water levels in locks and docks. Valves were formerly, in some cases, built into the gates, but, as the vol ume of water to be dealt with grew larger it became usual to build culverts with controlling gates in the side walls of the lock or entrance. Gate sluices are, however, still used in some docks for the purpose of sluicing silt deposits from the sill apron. An old form of sluice gate or "paddle," still largely employed, is constructed of timber, usually greenheart, and is raised and low ered over the culvert mouth in the sluice chamber by hand power or hydraulic gear. Cast iron gates faced with gun-metal and working against cast iron frames are often employed and these are usually operated by hydraulic or electric machines. A double faced sluice gate at the Congella dry dock, Durban, is illustrated in fig. 20. Balanced cylindrical sluice valves, in which the water flows between the bottom edge of a steel cylinder and its annular seating when the cylinder is raised, are used in some cases. Roller gate sluices of the Stoney pattern are frequently em ployed in large culverts as at the locks of the Panama canal and "butterfly" or balanced flap sluice valves turning about a hori zontal axis are occasionally used in culverts of moderate dimen sions. Cylindrical and "butterfly" valves both possess the advan tage, in that they are balanced, or in equilibrium so far as water pressure is concerned, of eliminating friction at the meeting sur faces. In roller sluices the friction is reduced to insignificant di mensions. All dock sluices operated by electric motors or hydraulic rams should be fitted with means for hand working when neces sary. Stop paddles for emergency use are often provided in sec ondary sluice pits.

Dock Gates.

The entrances and locks at wet docks, and the entrances at dry docks are closed by either gates or caissons. Gates were formerly built of timber, greenheart being used very generally for that purpose in England. Until about 1915 prac tically all the gates at Liverpool were so constructed, even for such wide openings as oof t. at the Canada lock. The difficulty of obtaining very large greenheart timbers, its high cost since the war, and the convenience and economy of steel construction have resulted in the almost universal use of mild steel for gate building. During the second half of the last century many gates were built of wrought iron until the general adoption of mild steel for structural purposes superseded it. In steel gates the heel post, i.e., the vertical closing piece at the hinge end, the mitre post at the meeting end, and the sill piece or "clapping sill" which closes against the fixed sill of the gate chamber, are all usually built of greenheart or faced with it.Wooden gates consist of a series of horizontal framed beams, made thicker and placed closer together towards the bottom to re sist the water-pressure which increases with the depth. The beams are framed and fastened to the heel post and mitre post at the ends and there are usually intermediate uprights. On the inner face watertight planking is fixed (fig. 2 I) .

Steel gates have generally an outer as well as an inner skin of plating braced vertically and horizontally by steel plate ribs and girders. Steel gates have the important advantage over those built of timber in that they can be made with buoyancy chambers which relieve the gate anchorage at the head of the heel post of a great part of the horizontal stress, due to the weight of the gate, and the pivot support, at its foot, of all weight except so much as is necessary to prevent the gate floating out of its seat :mg. They are thus much easier to move in the water than wooden gates. On the other hand the latter are less likely to be seriously damaged if run into by a vessel. All anchorages and supports of a steel gate should, however, be made strong enough to sustain its weight in the event of the buoyancy chambers becoming water logged.

The adoption of the semi-buoyant type of steel gate, now generally employed in modern docks, has made it possible to dispense with the roller and roller path under the gate near the mitre post formerly provided to sustain the weight. These were always a source of trouble and anxiety and their use is now practically abandoned in new construction. The buoyancy of the gate is maintained at a practically constant value by construct ing the watertight air or buoyancy cham ber in the lower part of the gate, all the chambers formed by the skin plating above the watertight compartments being open on the outside face to the free flow of the tide. Thus, so long as the buoyancy cham bers are submerged, the unbalanced weight remains practically unchanged whatever the depth of water may be. In this way the unfloated weight of the gate can be reduced to a few tons.

Formerly dock gates were sometimes made segmental in plan on both faces with the inner faces forming a continuous circu lar arc. It is now usual to make gates with perfectly straight faces on the sill side, the pressure or inside faces being either curved or polygonal. Fig. 2 2 illustrates one of the Gladstone lock gates with curved inner face which weighs 496 tons. The width of a gate leaf at its centre is usually made about -A- of its length.

The pressures produced by a head of water against gates when closed depend not only on the form of the gates but also upon the projection given to the mitre of the sill in proportion to the width of the opening. This projection is called the "rise" of the gate and is usually about (more or less) the width of the open ing. In straight gates, the stresses consist : first, of a transverse stress due to the water pressure against the gate and, secondly, of a compressive stress along the gate, resulting from the pres sure of the other gate against its meeting post. This pressure varies inversely with the rise. Though an increase in the rise re duces this stress, it increases the length of the gate and the transverse stress, and also the length of the chamber. By curv ing the gates, the transverse stress is reduced and the longitudinal compressive stress is augmented, till at last, when the gates f orm a horizontal segmental arch, the stresses become wholly compres sive. The straight fronted and curved or straight backed gate now usually adopted is a compromise mainly dictated by prac tical considerations. Gates are, however, always designed so that the horizontal line of thrust falls within the skin plating.

Storm gates, pointing in the reverse direction to the Impounding gates and placed outside them, are occasionally employed in en trances which are subjected at times to extraordinarily high tides, floods or strong wave action. Strut gates are auxiliary hinged and framed shores, housed at the back of the gate recess. They can be swung into position at the back of the impounding gates to support them against the pressure of waves at or about high water in exposed situations. Single leaf semi-buoyant gates, hinged on a horizontal axis below the level of the sill, have been used in some dry dock entrances. The gate is lowered into the water to open the entrance until it lies flat on a platform or apron outside and below the level of the sill.

Gate Machinery.

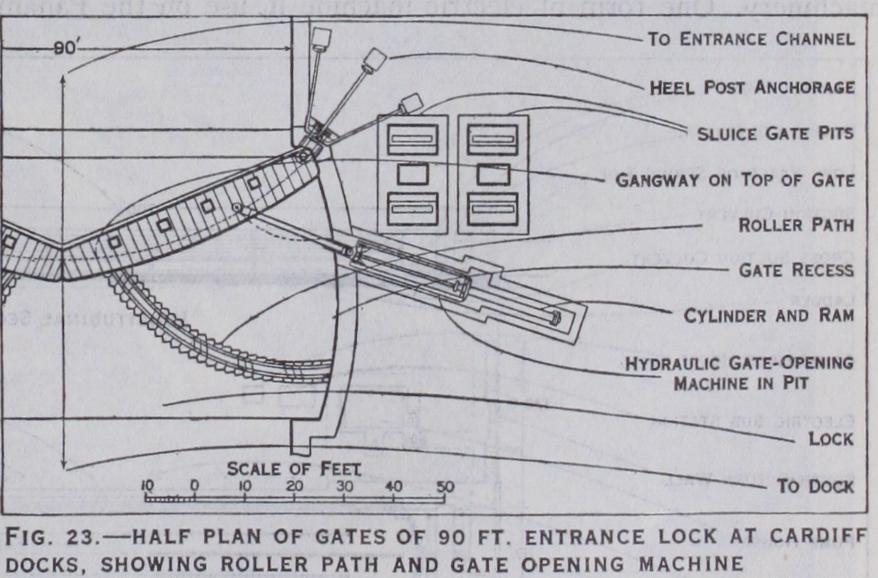

Gates are opened and closed by various means. The old practice, still used for many gates of moderate size, was to attach two chains to each gate, one leading to each side of the entrance. These chains are hauled by hand winches or capstans, or some form of power machine such as a hydraulic engine or electric winch. When the gates are opened the slack chain is run out so that it lies across the chamber floor. Direct acting hydraulic rams, placed in covered pits just below the coping level of the lock, were first introduced about 1889 at the Barry docks. This system, in an improved form (fig. 23), has been widely adopted, particularly in Great Britain, and is still in general use. On the continent of Europe and in America electric power has been generally employed in recent years for operating gate machinery. One form of electric machine in use on the Panama canal consists of a large horizontal spur wheel linked, at one point on its circumference, to the gate by a connecting rod and rotated by an electric motor through gearing. In opening the gate the spur wheel turns through about a half circle. Another type used both in America and on the continent of Europe employs a con necting rod in the form of a rack which is engaged by worm gearing driven by an electric motor. In all these cases the operat ing machinery is placed in pits at the side of the lock.

Dock

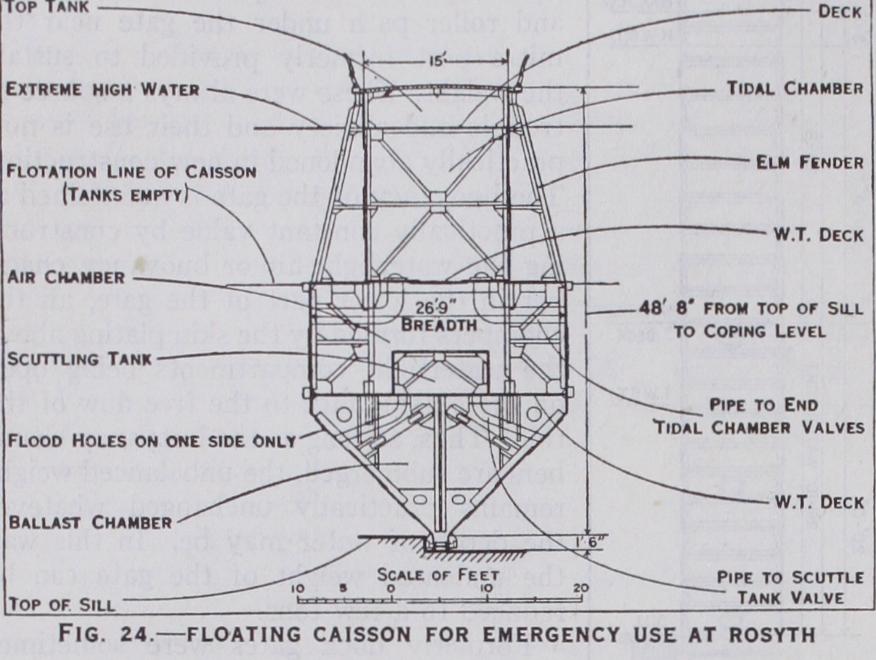

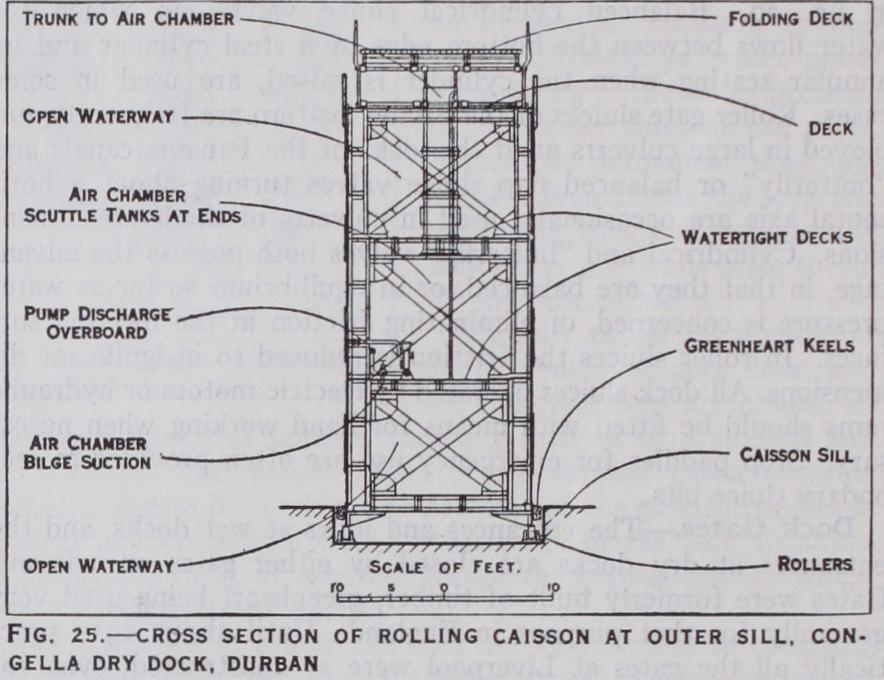

Caissons.—Caissons for closing the entrances of wet docks, dry docks and locks are constructed with buoyancy and ballast tanks so that, by means of valves and a pump or ejector fitted in the caisson, the weight of the contained water ballast can be varied at will for the purpose of floating or sinking the caisson or adjusting the unbalanced weight. Caissons are fitted with greenheart sill pieces and meeting faces which close against the granite faced sills and stops provided in the dock or lock entrance. They are of three general types: (a) floating caissons which are either ship form or rectangular and are moved with out guides or rollers; (b) sliding caissons, provided with green heart or other keel pieces which rest on sliding ways of smooth granite over which the caisson is drawn; and (c) rolling caissons, having wheels fixed to the under side on which they travel over rails laid on the floor of the entrance. In some cases the wheels or rollers are attached to the floor and the rails to the caisson.

The second and third types require a long recess or "camber" to be formed in the side of the entrance into which the caisson may be withdrawn when the passage is to be opened. In a few cases, e.g., a dry dock at Dundee, floating caissons have been hinged at one end and arranged to swing out into a recess in the dock wall. Floating caissons are in use for closing many dry docks. They are also often provided at wet docks for emergency use and for closing entrances when a sliding caisson is, or gates are, taken out for repairs (fig. 24) .

One of the earliest examples of a rolling caisson was used at the Garvel dry dock, Greenock, in 1874. Other instances of their use are at the entrance lock of the Bruges ship canal, the Congella dry dock, Durban (1925) (fig. 25) ; the Kruisschans lock, Ant werp (1927) ; and the new Ymuiden lock (1928). The three caissons at the latter are the largest in the world.

For closing the entrances of large dry docks sliding caissons have been adopted in many recent instances (see table III.) . They are employed less frequently in the case of wet docks and locks, but of this use there are, however, important examples. Thus, most of the recent naval wet dock entrances in Great Britain, including Rosyth and Portsmouth, are closed by sliding caissons as is also the i 4of t. entrance, made in 1917, at Cammell Laird & Co.'s fitting out dock at Tranmere on the Mersey. Among commercial docks they are in use at Bremen and Bremerhaven, and at the Ramsden dock, Barrow. A recent example is the Calcutta lock (building, 1928).

A floating caisson is occasionally made to draw back into a camber and in this form differs but slightly from a sliding cais son. The large dry dock at Havre (19 2 7) is closed by a caisson of this type. Sliding or rolling caissons, although more costly than simple floating caissons, are more easily and rapidly moved.

In situations where it is necessary to provide for carrying a road or railway over a sliding or rolling caisson, one or other of two methods is usually adopted for effecting this. In the first the cam ber is covered by a fixed roof carrying the rail tracks, and a lower ing platform forms the deck of the caisson and is depressed before the latter is hauled into the recess (fig, 25). In the alternative arrangement the roof of the camber itself is carried on elevating jacks which raise it sufficiently to allow the caisson to be run in under it, only the guard railings at the sides of the caisson deck being lowered. A modification of this arrangement is used in British naval docks. The ways on which the caisson slides are formed on a gradient sloping downwards into the camber and the movable deck is hinged at the inner end and raised at the outer end to allow the caisson to pass under it. The caisson when in the camber is at a level which will allow the deck to be again lowered into its normal position flush with the coping.

Sliding and rolling caissons are hauled in and out of the cam bers by means of wire ropes or chains and hauling machinery. The large sliding caisson at Portsmouth is hauled by compressed air motors; those at Rosyth, the Gladstone dry dock, Liverpool, and the Congella dock, Durban, in South Africa, are operated electrically.