Damascus

DAMASCUS, the name of a Sanjak and town of Syria, 57 m. from Beirut and situated in 33° 3o' N. and 36° 18' E. Its origin is unknown, and the belief that it is the oldest city in the world still inhabited has much to recommend it. It is tioned in the account of the battle of the four kings against five, in the book of esis (ch. xiv.), where Abram (Abraham) is reported to have pursued the routed kings to Hobah north of Damascus (v.15).

In the period of the Egyptian suzerainty over Palestine in the i8th dynasty Damascus (whose name frequently appears in the Tell el-Amarna tablets) was capital of the province of Ubi. The name of the city in the Tell el-Amarna correspondence is Di mashka. Towards the end of that period the overrunning of Palestine and Syria by the Khabiru and Sutu evidently changed the conditions, language and government of the country, and the Aramaean form, Darmesek, appears in an inscription of Rameses III.

Damascus soon reached such strength that though Tiglath Pileser I. reduced the whole of northern Syria, and by the fame of his victories induced the king of Egypt to send him presents, yet he did not venture to attack Kadesh and Damascus, so that this kingdom acted as a "buffer" between Assyria and the rising kingdom of Israel.

David made an expedition (2 Sam. viii) against Damascus as a reprisal for the assistance the city had given his enemy Hada dezer, king of Zoba. The Israelite possession of Syria did not last long. A subordinate of Hadadezer named Rezon (Rasun) suc ceeded in founding a dynasty there, and throughout Solomon's reign he was a constant enemy to Israel (1 Ki. xi. 23 seq.).

It is inferred from I Ki. xv. 19 that Abijah, son of Rehoboam, king of Judah, made a league with Tab-Rimmon of Damascus to assist him in his wars against Israel, and that afterwards Tab Rimmon's son Ben-Hadad came to terms with the second suc cessor of Jeroboam, Baasha. Asa, son of Abijah, followed his father's policy, and bought the aid of Syria, whereby he was en abled to destroy the border fort that Baasha had erected (1 Ki. xv. 22). Hostilities continued between Israel and Syria. Syria established a quarter for Syrian merchants in Samaria (1 Ki. xx. 34•)• A Syrian defeat at Aphek, when the king of Israel acted too leniently, was the cause of a prophetic denunciation (1 Ki. xx. 42).

According to the Assyrian records Ahab fought as Ben-Hadad's ally at the battle of Karkar against Shalmaneser in 853 B.C. This seems to indicate the vassalage of Ahab, of which no direct record remains ; and it was perhaps in the attempt to throw this off that he met his death in battle (1 Ki. xxii. 34-4o). In the reign of Jehoram, Naaman, the Syrian general, came and was cleansed by the prophet Elisha of leprosy (2 Ki. v.) .

In 842 Hazael assassinated Ben-Hadad and made himself king of Damascus. The states which Ben-Hadad had brought together into a coalition against the advancing power of Assyria all re volted ; and Shalmaneser, king of Assyria, took advantage of this and attacked Syria (841) . He wasted the country, but could not take the capital. Jehu, king of Israel, paid tribute to Assyria, for which Hazael afterwards revenged himself, during the time when Shalmaneser was distracted by his Armenian wars, by attacking the borders of Israel (2 Ki. x. 32).

Adad-nirari III. invaded Syria and besieged Damascus, c. 805-802 ; and Jehoash, king of Israel, seizing the opportunity, recovered the cities that his father had lost to Hazael. In 735 Ahaz of Judah was attacked by Rezon (Rasun, Rezin), king of Damascus; at the same time the Edomites and the Philistines revolted. The king of Assyria, Tiglath-Pileser III., was besought to help; and, invading Syria, reduced Damascus in 733.

Except for the abortive rising under Sargon in 72o, we hear nothing more of Damascus for a long period. In 333 B.e., after the battle of Issus, it was delivered over by treachery to Parmenio, the general of Alexander the Great. It had a chequered history in the wars of the successors of Alexander, being occasionally in Egyptian hands. In i 12 B.C., the empire of Syria was divided by Antiochus Grypus and Antiochus Cyzicenus; the city of Damascus fell to the share of the latter. Hyrcanus took advantage of the disputes of these rulers to advance his own kingdom. Demetrius Eucaerus, successor of Cyzicenus, invaded Palestine in 88 B.C., and defeated Alexander Jannaeus at Shechem. On his dethrone ment and captivity by the Parthians, Antiochus Dionysus, his brother, sL cceeded him, but was slain in battle by Haritha (Aretas) the Arab. Haritha yielded to Tigranes, king of Armenia, who in his turn was driven out by Q. Caecilius Metellus. In 63 B.c. Syria was made a Roman province.

In the New Testament Damascus appears only in connection with Acts ix., xxii., xxvi., 2 Cor. xi. and Gal. i. In A.D. 106 under Trajan, Damascus became a Roman provincial city. On the establishment of Christianity Damascus became the seat of a bishop who ranked next to the patriarch of Antioch, and the great temple of Damascus was turned into a Christian church.

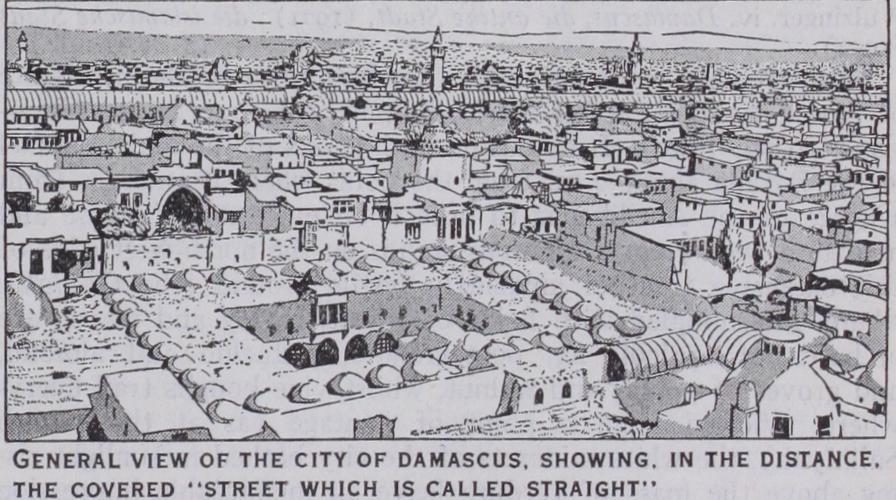

In 635 Damascus was captured for Islam by Khalid Ibn Welid. After the murder of Ali, the fourth caliph, his successor Moawiya transferred the seat of the Caliphate (q.v.) from Mecca to Damascus and thus commenced the great dynasty of the Omayyads, whose rule extended from the Atlantic to India. Ninety years later it was supplanted by that of the Abbasids, who removed the seat of empire to Mesopotamia; and Damascus passed through a period of unrest in which it was captured and ravaged by Egyptians, Carmathians and Seljuks in turn. The crusaders attacked Damascus in 1126, but never succeeded in keeping a firm hold of it. It was the headquarters of Saladin in the wars with the Franks. The chief later events are the Mon golian capture in 1260, its Egyptian recapture by the Mameluke Kotuz; the ferocious raid of Timur (Tamerlane) in 1399; and the conquest by the Turkish sultan Selim, whereby it became a city of the Ottoman empire 0516). Of its more recent history, one may mention the massacre of July 186o, when the Muslim population rose against the Christians, burnt their quarter, and slaughtered about 3,00o adult males. (See SYRIA.) See also Kraeling, Aram and Israel (New York, 1918) ; Wissen schaftliche Vero ff entlichungen des Deutsch-Turkischen Denkmalschutz Kommandas, edit. Theodor Wiegand, Carl Watzinger and Karl Wufzinger, iv. Damascus, die antike Stadt, (1921) ; die islamische Stadt • (S. A. C.; X.) Modern City.—Damascus is the chief town of the new state of Syria; 2,200 ft. above sea-level; pop. 188,000 (21,000 Chris tians, 16,000 Jews). It stands on both banks of the main channel of the Barada about 2 m. from the point where it emerges from a gorge of the Antilibanas to branch off eventually fanwise and irrigate a wide area. Damascus stands on the north-west edge of this extensive tract of amazingly fertile ground (the Ghutah), where, intermingled with fields of wheat, barley and maize, are orchards of apricot, fig, pomegranate, pistachio and almond, and groves of poplar and walnut, whilst vine boughs trail every where. Viewed from a point of vantage (as at the suburb Salihiyah), the white minarets of the city bathed in sunlight ris ing above the mass of verdure leave an ineffaceable impression on the mind of the beholder. The ancient city, rudely rectangular in shape, was huddled within a wall on the southern bank of the Barada. The modern city is spoon-shaped, the handle to the south whither the city has been drawn a long way on the Meccan road forming the quarter known as the Meidan. A suburb, El-Amara, has been built on the northern bank, and farther off towards the north-west is another suburb, Saliliiyah. Damascus is supplied with water from the Barada by an extensive system of canals and conduits. Its streets, for the most part narrow and protected overhead, are by no means clean, and the high walls which con ceal private dwellings belie the magnificence to be found within. Its public buildings, mosques, schools and Khans reveal many fine examples of Arabian art. To a partial extent sheltered by hills to the north, west and south, the city lies open to the east and its trying and prevalent winds. It suffers a great variation in temperature in the course of the year. In winter frost and snow are not unknown, and summer temperatures are high but the nights are always cool. Fever, dysentery and ophthalmia due to the climatic conditions are prevalent.

In recent, as in earlier times, the development of the city has been affected by great outbreaks of fire. The Great Mosque was gutted in 1893, and in 1912 a conflagration destroyed a con siderable tract of bazaars. Great damage was done by the French bombardments of Oct. 1925 and May 1926. It is said that Damascus has 24o mosques, mostly dilapidated, of which 70 are still in use. Catholic and Protestant missions support a large number of educational institutions and hospitals. The municipal ity has erected a public hospital and a hospital for lepers. There is a resident British consul.

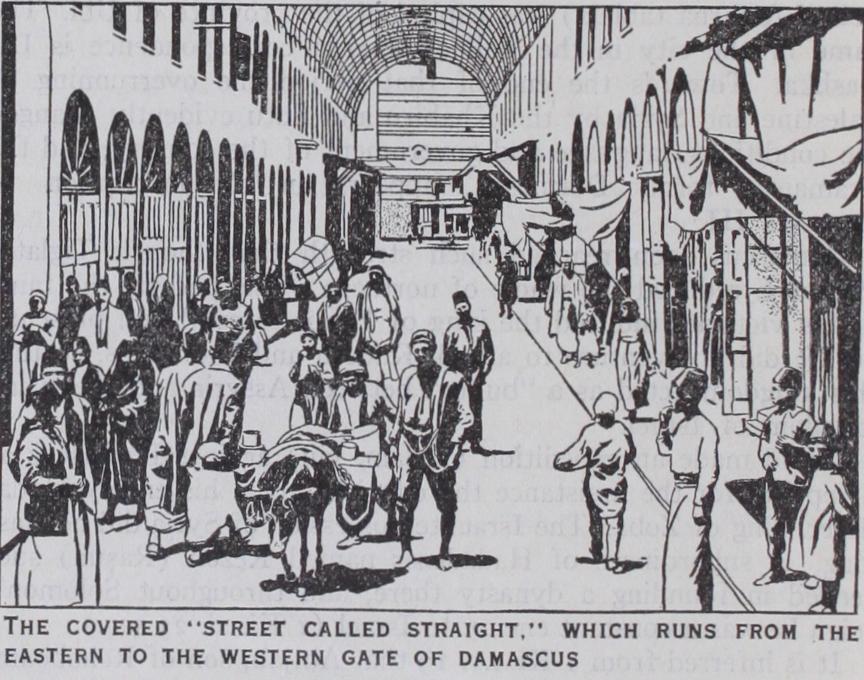

Antiquities.

The ground plan of the city may be said to have remained unaltered since the Mohammedan occupation at least, and a conflagration such as reduced the city to ashes in 140I merely cleared the site for fresh building. Material and facilities for archaeological study are consequently less than might have been expected. The hand of the Roman workman is visible in what is left of the city walls and gates, in the area of the Great Mosque, in the Darb-el-Mustakim, which was prob ably colonnaded, and in an aqueduct in the western quarter. The Great Mosque (or Umayyad mosque) was originally the Church of St. John Baptist, whose building was begun by the emperor Theodosius (375) and completed by his son Arcadius It occupied the site of an earlier temple, probably that of Rim mon (cf. 2 Ki. v. 18) . The Caliph El-Watid deprived the Chris tians of their building (A.D. 705), and destroyed it in great part before re-erecting it as a mosque. It was burned down in 1069, pillaged by Tamerlane (14or) and badly damaged by fire (1893). In this mosque in 1905 some valuable Syriac and Kufic manu scripts were discovered. The citadel in the north-west of the city was built in 1219 by Malik el-Ashraf, refortified by Beibars (1262) and by the Turks (i6th century) . The French have established an Institute of Mohammedan Archaeology and Art (its archaeological collection suffered heavily from fire and pillage in Oct. 1925), and a School of Arabic Decorative Art to revive the work in glass and wood and the colouring of stuffs. They aim at reproducing the best Arabic work of the best period. A new Syrian National Museum has also been instituted.Commerce.—From its happy situation Damascus has ever had much to offer to the nomad and from the earliest times it has been the market of the desert. Ezekiel (xxvii. 18) mentions its "wine of Helbon" and its wool. In classical times it had a reputation for its Chalybonian wine (i.e., of Helbon, mod. Halbun, 13 m. N.N.W. of Damascus). Its dried fruits (pruna et cottana: Juvenal iii. 83) were a valued present, and its linens, cloths and cushions were famous. For centuries the "Damascene blade" carried far afield the reputation of the city's armourers. Diocle tian promoted this industry but it perished when Tamerlane carried off the smiths in 1401. The silk looms are not so im portant now as of old, but modern industries such as leather work, the filigree work of gold and silversmiths (who are all Christians), inlaid work in wood and metal (brass, copper), have survived. Damascus was hard hit by the World War and in lustry has revived but slowly. Egypt since the war has begun to manufacture goods previously made in Syria and many artisans From Damascus have migrated thither. The textile industry suf fers from foreign competition, and dyeing has declined in sym pathy. Railway connection with the Hauran (1894), Beirut (1895) and Haifa (19o5) has diminished its caravan trade. Damascus is tending more and more to become a centre for Foreign imported goods as well as local produce, and with the development of motor transport an increase in transit trade may be expected. The shops of Damascus are famous for the wealth and variety of their goods and its streets for the mixture of races that throng them.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.—A. V. Kremer, Topographie von Damaskus (1854), Bibliography.—A. V. Kremer, Topographie von Damaskus (1854), z vols. ; J. L. Porter, Five Years in Damascus (185 5) , 2 vols.; Sir G. A. Smith, Historical Geography of the Holy Land (1895 Ac.) ; Hastings, Dictionary of the Bible (W. Ewing), Encyc. of Islam (R. Hartmann) ; C. Watzinger u. K. Wulzinger, Damaskus, lie Antike Stadt (1921) ; R. Dussaud, Le Temple de Jupiter Damas ;enien et ses transformations aux epoques Chretienne et mussulmane; Syria, 1922, 219 seq.; J. E. Hannaver, Damascus; Notes on changes made in the city during the Great War: Pal. Expl. Fund Quart. Statement, 1924, 68 sq.; Syria and Palestine Guide Books; Consular Reports and Reports of Department of Overseas Trade. (E. Ro.) Prior to the World War, Damascus was the headquarters of the IV. Turkish Army, and after the outbreak of hostilities be came the base of the Turkish and German forces operating in Palestine and on the east bank of the Suez Canal under General Liman von Sanders. On Oct. r, 1918, the city fell into the hands of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force under Lord Allenby (q.v.) and the Arab troops of the Emir Feisal (q.v.). The advance on Damascus was a purely cavalry operation, and at the city itself no resistance was made to the British and Arab troops. By Sept. 3o the Australians had worked round the north; the desert column was lying to the west ; and the Arab force was at the southern outskirts of the city. Itlost of the Germans and Turks, of ter severe quarrelling, had already left.

During the night of Sept. 3o troops of the Australian Mounted Division and the advanced guard of Feisal's force had made their way into the city, and both claimed to be the first to set foot in Damascus. The formal entry was made at 6 A.M. on Oct. 1 when a British detachment and part of the Arab army marched through the streets. About 7 ,000 Turks surrendered to the Allied forces. On Oct. 3 Feisal made his official entry into Damascus, and this he did, according to ancient custom, by riding furiously through the streets with a large number of kinsmen, to the accompaniment of a feu de joie and the piercing shouts of the Arab population. After the formal occupation the Allied troops were withdrawn and an Arab administration under Feisal was set up. Sukry Pasha El Ayyubi, senior descendant of Saladin, was appointed head of the administration of the city.

Feisal and the French.—When in Nov. 1919 General Gou raud was nominated French High Commissioner for Syria, the Feisal regime in Damascus was strongly antagonistic to the French and productive of much disorder. Raiding and pillaging were encouraged and public money was misappropriated. Finally, on March 7, 192o, Feisal was elected King of Syria by a so-called General Syrian Congress, while the material opposition to French influence increased and the Arab army steadily grew in numbers. Eventually matters became so serious that in July 192o General Gouraud had to issue an ultimatum. Feisal delayed his reply and questioned the terms, while an Arab detachment attacked one of the advanced French posts, with the result that a French force took up its position at `Ain el Jedeida, on the road from Beirut to Damascus, two days before the delivery of Feisal's reply. As Feisal still refused to accept certain conditions, the French force advanced and, after a fierce combat at Khan Meizalun with some 20,000 Arabs, entered Damascus. Feisal with his chief councillors took to flight.

On June 20, 1921, the Syrian Confederation, consisting of the state of Aleppo, Damascus and the Alaouites, was proclaimed at Damascus and, in order to preserve an equal balance between the north and the south, the city had to share the capital honours with Aleppo. This was superseded later by the establishment of one capital at Damascus, and in 1925, at the wish of the in habitants, Damascus became the capital of the Syrian State comprising the two districts of Damascus and Aleppo under a president with a French adviser as High Commissioner's On April 8 and 9, 1925, the visit of Lord Balfour to Damascus was the occasion of considerable rioting, nominally as a protest against the Zionist declaration, bearing his name, but more generally recognized as a demonstration of anti-French feeling.

The Druses.—When the Druse rebellion (see DRVSES) broke out in July 1925, Damascus played an important part as the French advanced base and as the key to the general situation in Syria. The Damascenes were sympathetic to the Druses and, their discontent being aggravated by an exceptionally bad harvest a general rising was feared with serious consequences in other Syrian towns. Two attempts were made by the Druses to effect a Damascene rising by attacks on the city. The first was a complete failure, but the second attack of Oct. 18 was a great deal more serious. Bands of Druses entered Damascus from the south and, receiving the support of the lower elements of the population, overran certain quarters, looting and pillaging as they went. Most of the inhabitants, however, disappointed at the small numbers of the Druses, failed to take any decisive action. French troops were sent into the streets to repel the insurgents, but, as the situation became more serious, the French troops were with drawn and the order was given to bombard the affected areas. The bombardment lasted until Oct. 20, and great damage was done, including the partial destruction of the Palais Azm, recognized as the most beautiful building in the city.

This action of General Sarrail (q.v.), the French High Com missioner, was severely criticised, and he incurred well-merited censure for permitting the situation in Damascus to become such that a bombardment was a military necessity, and for carrying out such a drastic measure without issuing either an ultimatum to the inhabitants or notices to the foreign consuls. General Sarrail was recalled to France in November of the same year. His dis missal, however, brought no peace to Damascus, and fighting con tinued around the city.

In Dec. 1925, M. Henri de Jouvenel (q.v.) succeeded General Sarrail as High Commissioner for Syria and in Feb. 1926, after the resignation of Subky Bey Barakat, President of the Syrian State, a Provisional Government was set up under M. Pierre Alype, with General Andrea as Military Governor of Damascus. In April of the same year, M. Alype was replaced by a native Provisional Head of the State in the person of Damad Ahmed Nami Bey, who governed through a Council of Ministers with French advisers. As martial law still prevailed, Damascus was excluded from the areas in which elections were subsequently held.

On May 7, 1926, Damascus was again the scene of serious disturbances. A Druse band, about 200 strong, penetrated into the Meidan quarter, which was bombarded, at half an hour's notice, by French artillery and aircraft. The greater part of the Meidan quarter, which contains one-quarter of the population of Damascus, was destroyed, while i,000 lives are said to have been lost. The value of the damage was estimated at £700,000. On this occasion the street fighting on the French side was con ducted, not by French regular troops, but by Circassian and Armenian levies, who were accused of savage brutality. Even this second devastation of Damascus failed to produce the effect desired by the French.

At the end of May, 1926, M. de Jouvenel accorded the Syrian President the right to offer an amnesty to all rebels, who should lay down their arms in Damascus by June 15; he abolished the indemnity of oo,000 Syrian pounds imposed upon the city as a result of the insurrection of Oct. 1925; and approved the pro gramme of the National Syrian Government. These conciliatory measures, however, had no satisfactory result, the Syrian 1VIin istry was dissolved for showing undue sympathy to the in surgents, and desultory fighting continued in and about Damascus. Finally, after the arrival of M. Ponsot as High Commissioner, the Syrian revolt began to subside at the end of 1926. By this time it was possible to re-establish road communications with Beirut, and Damascus began to regain its commercial position on the trade route to Iraq via the Syrian Desert.

Meanwhile, the city had been placed in a strong state of defense by General Andrea, and the clearances made for this purpose were utilized for the construction of the "Boulevard de Baghdad," a broad thoroughfare encircling the city. A comprehensive scheme of town-planning was also inaugurated, including the restoration of the bombarded area, and plans for approved facades were prepared by M. de Lorey, Directeur de l'Institut francais d'ar cheologie et d'art mussulman. Provision was thereby made that the new quarter of Damascus should not clash with its ancient sur roundings.