Dial

DIAL and DIALLING. Dialling, sometimes called gno monics, treats of the construction of sundials, that is, of those instruments, either fixed or portable, which determine the di visions of the day (Lat. dies) by the motion of the shadow of some object on which the sun's rays fall. It must have been one of the earliest applications of a knowledge of the apparent mo tion of the sun; though for a long time men would probably be satisfied with the division into morning and afternoon as marked by sunrise, sun-set and the greatest elevation.

History.

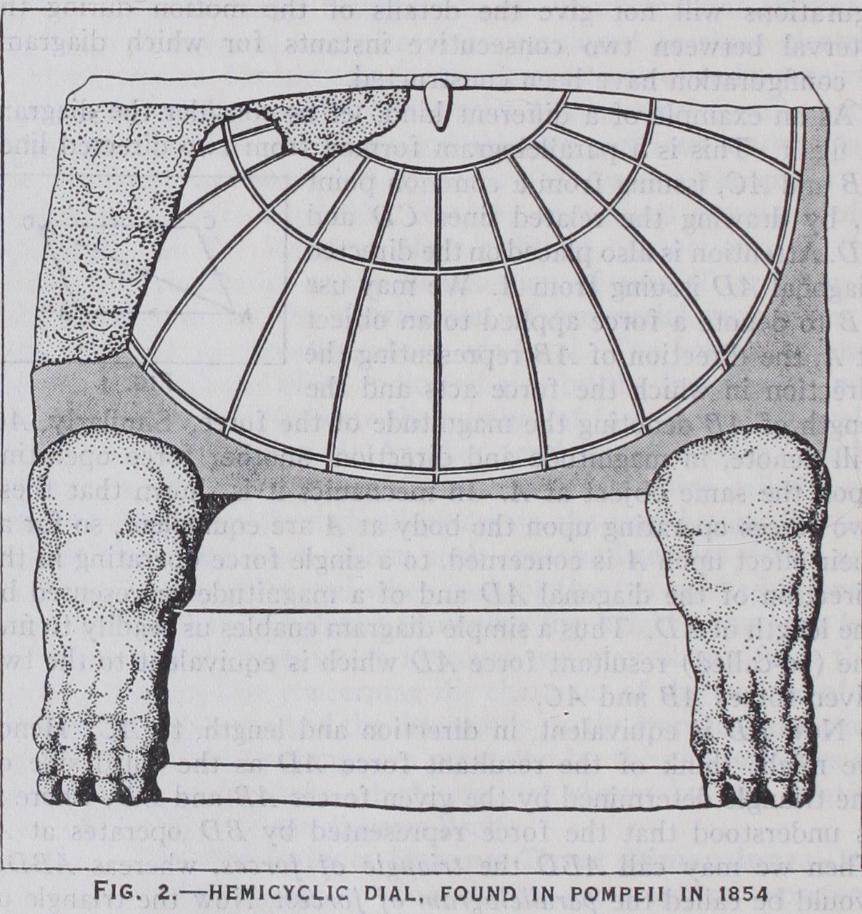

The earliest mention of a sundial has been thought to be found in Isaiah xxxviii. 8 : "Behold, I will bring again the shadow of the degrees, which is gone down in the sundial of Ahaz, ten degrees backward." But a more correct translation may be "down the steps of Ahaz, zo steps backwards." The date of this would be about 70o years before the Christian era, but there is no evidence that there was a sundial. The earliest of all sundials of which we have any certain knowledge is a _I -shaped Egyp tian dial in the Berlin museum, in which the upright of the J throws longer or shorter shadows along the horizontal limb which is divided into six hours. Another early classical type was the hemicycle, or hemisphere, of the Chaldean astronomer Berosus, who probably lived about 30o B.C. It consisted of a hollow hem isphere placed with its rim perfectly horizontal, and having a style, the point of which was at the centre. So long as the sun remained above the horizon the shadow of the point would fall on the inside of the hemisphere, and the path of the shadow during the day would be approximately a circular arc. This arc, divided into i 2 equal parts, determined i 2 equal intervals of time for that day. Now, supposing this were done at the time of the solstices and equinoxes, and on as many intermediate days as might be considered sufficient, and then curve lines drawn through the corresponding points of division of the different arcs, the shadow of the bead falling on one of these curve lines would mark a division of time for that day, and thus we should have a sundial which would divide each period of daylight into 12 equal parts. These equal parts were called temporary hours; and, since the duration of daylight varies from day to day, the tempo rary hours of one day would differ from those of another ; but this inequality would probably be disregarded at that time, and es pecially in countries where the variation between the longest summer day and the shortest winter day is much less than in our climate.The dial of Berosus remained in use for centuries. The Ara bians, as appears from the work of Albategnius, still followed the same construction about the year A.D. 900.

Herodotus recorded that the Greeks derived from the Baby lonians the use of the gnomon, but the great progress made by the Greeks in geometry enabled them in later times to construct dials of great complexity and ingenuity. Ptolemy's Almagest treats of the construction of dials by means of his analemyna, an instrument which solved a variety of astronomical problems. The constructions given by him were sufficient for regular dials, that is, horizontal dials or vertical dials facing east, west, north, or south, and these are the only ones he treats of. It is certain, however, that the ancients were able to construct declining dials, as is shown by that most interesting monument of ancient gnomics—the Tower of the Winds at Athens. This is a regular octagon, on the faces of which the eight principal winds are rep resented, and over them eight different dials—four facing the cardinal points and the other four facing the intermediate direc tions. The date of the dials is apparently coeval with that of the tower; for there has been found at Tenos a marble block with similar dials inscribed with the name of Andronicus Kyrrhestes, the builder of the tower. The hours are still the temporary hours or hectemoria.

The first sundial erected at Rome was in the year 290 B.C., and this Papirius Cursor had taken from the Samnites; but the first dial actually constructed for Rome was made in 164 B.C., by order of Q. Marcius Philippus. Vitruvius mentions 13 kinds of dials, including portable dials, the most interesting examples of which are the "Ham" dial, excavated at Herculaneum and the ad justable circular dial in the Lewis Evans collection at Oxford.

The Arabians were much more successful. They attached great importance to gnomonics, the principles of which they had learned from the Greeks; but they greatly simplified and di versified the Greek construc tions. One of their writers, Abu'l Hassan, who lived about the beginning of the i3th cen tury, taught them how to trace dials on cylindrical, conical, and other surfaces. He even intro duced equal or equinoctial hours which were used for astronomi cal purposes while the tem porary hours alone continued in use.

The great and important step already conceived by Abu'l san, and perhaps by others, of reckoning by equal hours, was probably adopted between the i3th to the beginning of the i6th century. The change would necessarily follow the introduction of striking clocks in the earlier part of the fourteenth century; for, however imperfect these were, the hours they marked would be of the same length in summer and in winter, and the discrepancy between these equal hours and the temporary hours of the dial would soon be too important to be overlooked. Now, we know that a striking clock was put up in Milan in 1336, and we may reasonably suppose that the new sundials came into gen eral use during the i4th and sth centuries.

Among the earliest of the modern writers on gnomonics was Sebastian Miinster (q.v.), who published his Horologiographia at Basle in 1531. He gives a number of correct rules, but without demonstrations. Among his inventions was a moon-dial. A dial adapted for use as a moon-dial when the moon's age is known, may be seen in Queens' college, Cambridge.

During the i7th century dialling was a special branch of edu cation. The great work of Clavius, a quarto volume of Soo pages, was published in 1612, and may be considered to contain all that was known at that time.

In the i8th century clocks and watches began to supersede sundials, and the latter gradually fell into disuse, except dials in a garden or in remote country districts, where the old dial on the church tower still serves as an occasional check on the modern clock by its side.

General Principles.

The daily and the annual motions of the earth are the elementary astronomical facts on which dialling is founded. That the earth turns upon its axis uniformly from west to east in 24 hours and that it is carried round the sun in one year at a nearly uniform rate is the correct way of expressing these facts. But the effect will be precisely the same, and it will suit our purpose better and make our explanations easier, if we adopt the ideas of the ancients, of which our senses furnish apparent confirmation, and assume the earth to be fixed. Then, the sun and stars revolve round the earth's axis uniformly from east to west once a day—the sun lagging a little behind the stars, making its day some four minutes longer—so that at the end of the year it finds itself again in the same place, having made a complete revolu tion of the heavens relatively to the stars from west to east.The fixed axis about which all these bodies revolve daily is a line through the earth's centre; but the radius of the earth is so small, compared with the enor mous distance of the sun, that, if we draw a parallel axis through any point of the earth's surface, we may safely look on that as being the axis of the celestial motion. The error in the case of the sun would not, at its maximum, that is, at 6 A.M. and 6 P.M., exceed half a sec ond of time, and at noon would vanish. An axis so drawn is in the plane of the meridian, it points to the pole, and its eleva tion is equal to the latitude of the place.

The diurnal motion of the stars is strictly uniform, and so would that of the sun be if the daily retardation of about four minutes, spoken of above, were always the same. But this is con stantly altering, so that the time, as measured by the sun's motion, and also consequently as measured by a sundial, does not move on at a strictly uniform pace. This irregularity, which is slight, would be of little consequence in the ordinary affairs of life, but clocks and watches being mechanical measures of time could not, except by extreme complication, be made to follow it.

A clock is constructed to mark uniform time in such wise that the length of the clock day shall be the average of all the solar days in the year. Four times a year the clock and the sun dial agree exactly ; but the sundial, now going a little slower, now a little faster, will be sometimes behind, sometimes before the clock—the greatest accumulated difference being about 16 min utes for a few days in Novem ber. The four days on which the two agree are April r 5, June 15, Sept. r and Dec. 24.

Clock time is called mean time, that marked by the sundial is called apparent time, and the dif ference between them is the equation of time. It is given in most calendars and almanacs, frequently under the heading "clock slow," "clock fast." When the time by the sundial is known, the equation of time will at once enable us to obtain the corre sponding clock time, or vice versa.

The general principles of dial ling will now be readily under stood. The problem before us is the following :—A rod, or style, as it is called, being firmly fixed in a direction parallel to the earth's axis, we have to find how and where hour-lines of refer ence must be traced on some fixed surface behind the style so that when the shadow of the style falls on a certain one of these lines we may know that at the moment it is solar noon— that is, that the plane through the style and through the sun then coincides with the meridian ; again, that when the shadow reaches the next line of reference it is i o'clock by solar time, or, which comes to the same thing, that the above plane through the style and through the sun has just turned through the 24th part of a complete revolution; and so on for the subsequent hours, the hours before noon being indicated in a similar manner.

The position of an intended sundial having been selected, the surface must be prepared, if necessary, to receive the hour-lines. The style must be accurately fixed in the meridian plane, and must make an angle with the horizon equal to the latitude of the place. The latter condition will offer no difficulty, but the exact determination of the meridian plane which passes through the point where the style is fixed to the surface is not so simple.

The position of the XII o'clock line is the most important to determine accurately, since all the others are usually made to depend on this one. We cannot trace it correctly on the dial until the style has been itself accu rately fixed in its proper place. When that is done the XII o'clock line will be found by the intersection of the dial surface with the vertical plane which contains the style; and the most simple way of drawing it on the dial will be by suspending a plummet from some point of the style whence it may hang freely, and waiting until the shadows of both style and plumb-line co incide on the dial. This single shadow will be the XII o'clock line. In one class of dials, namely, all the vertical ones, the XII o'clock line is simply the vertical line from the centre ; it can, therefore, at once be traced on the dial face by using a fine plumbline. The XII o'clock line being traced, the easiest and most accurate method of tracing the other hour lines would, at the present day when good watches are common, be marking where the shadow of the style falls, when i, 2, 3, etc., hours have elapsed since noon, and the next morning by the same means the forenoon hour lines could be traced ; and in the same manner the hours might be subdivided into halves and quarters, or even into minutes. But formerly, when watches did not exist, the tracing of the I, II, III, etc., o'clock lines was done by calcu lating the angle each would make with the XII o'clock line.

Dials received different names according to their position : Horizontal dials, when traced on a horizontal plane ; Vertical dials, when on a vertical plane facing one of the cardinal points; Vertical declining dials, when on a vertical plane not facing a cardinal point ; Inclining dials, when traced on planes neither vertical nor horizontal (these were further distinguished as reclining when leaning backwards from an observer, proclining when leaning for wards) ; Equinoctial dials, when the plane is at right angles to the earth's axis, etc.

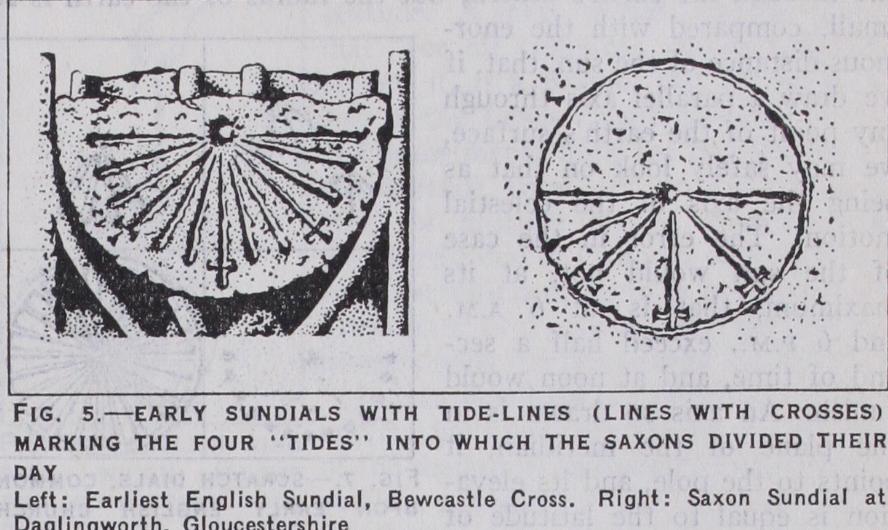

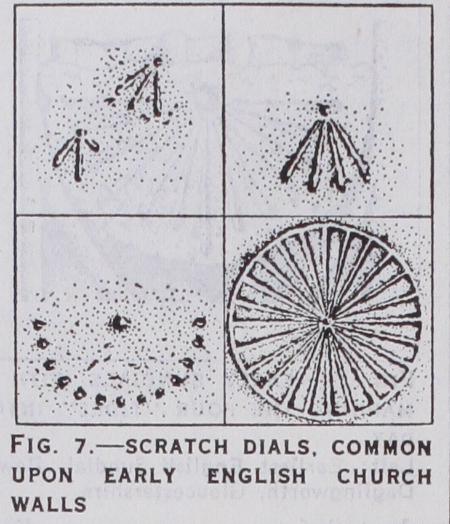

There are many early vertical south dials of great archaeolog ical interest on the walls of English churches. The simplest of all are the Anglo-Saxon dials, in which the day is divided into four tides of three hours each. A good example may be seen at Dagling worth. In the dial on Bewcastle Cross of the 7th century, hour lines have been intercalated between the early tide lines, which are marked with crosses. Upon church walls of the Early English period Scratch dials or Mass dials of various types are often found. In their simplest form they consist of a few hour lines radiating from a central hole in which a wooden style would have been inserted. A vertical noon line is always present. Lines at right angles to it would have been for 6 A.M. and 6 P.M., and one half way between the former and the noon line would have been for 9 A.M. Occasionally a circle of holes takes the place of the hour lines.

In the commonest type of horizontal dials the dial plate is of metal, as well as the vertical piece upon it, and they may be pur chased ready for placing on the pedestal, the dial with all the hour lines traced on it and the style plate firmly fastened in its proper position, or cast in the same piece with the dial plate.

When placing it on the pedestal care must be taken that the dial be perfectly horizontal and accurately oriented. The levelling will be done with a spirit level and the orientation will be best effected either in the forenoon or in the afternoon, by turning the dial plate till the time given by the shadow (making the small correction mentioned above) agrees with a good watch whose error on solar time is known. It is, however, important to bear in mind that a dial, so built up beforehand, will have the angle at the base equal to the latitude of some selected place, such as London, and the hour lines will be drawn in directions calculated for the same latitude. Such a dial, therefore, could not be used near Edinburgh or Glasgow, although, it would, without appreci able error, be adapted to any place whose latitude did not differ more than 20 or 3om. from that of London.

Portable Dials

were made generally of a small size, so as to be carried in the pocket ; and these, so long as the sun shone, answered the purpose of a watch. The description of the portable dial has often been mixed up with that of the fixed dial, as if it had been merely a special case, and the same principle had been the basis of both ; but although some are like the fixed dials, with the addition of some means for orientating the dial, others depend on the very irregularly varying zenith distance of the sun.Portable dials fall into two main classes : Altitude Dials and Compass Dials.

I. Altitude Dials find the time from the altitude of the sun, al lowance being made for the season of the year. An early example was the Roman Ham dial excavated at Herculaneum under the Vesuvian muds of the eruption of A.D. 79. It is marked with the months of July and August and must therefore be more recent than 2 7 B.C. It was only serviceable in one latitude. A more useful type of altitude dial "for all climates," as Vitruvius de scribes it, is a Roman dial of about A.D.

2 5o in the Lewis Evans collection, which has adjustments both for the seasons and for latitude from 30° to 60°. Another form of altitude dial is known as the Shepherd's dial or Cylinder dial. The earl iest description of them is by Hermannus Contractus (1013-1054), and they are still in use among the peasants in the Pyrenees.

In this type there is a horizontal gnomon and the hour lines are curves of the length of the shadow of this gnomon on a vertical surface, according to the hour and season.

These curves are drawn either on a cylin der or a flat surface. The seasons are repre sented by vertical lines, and the gnomon is moved to the appropriate line, the dial being so placed that the shadow falls perpendicularly and the hour read on the hour line.

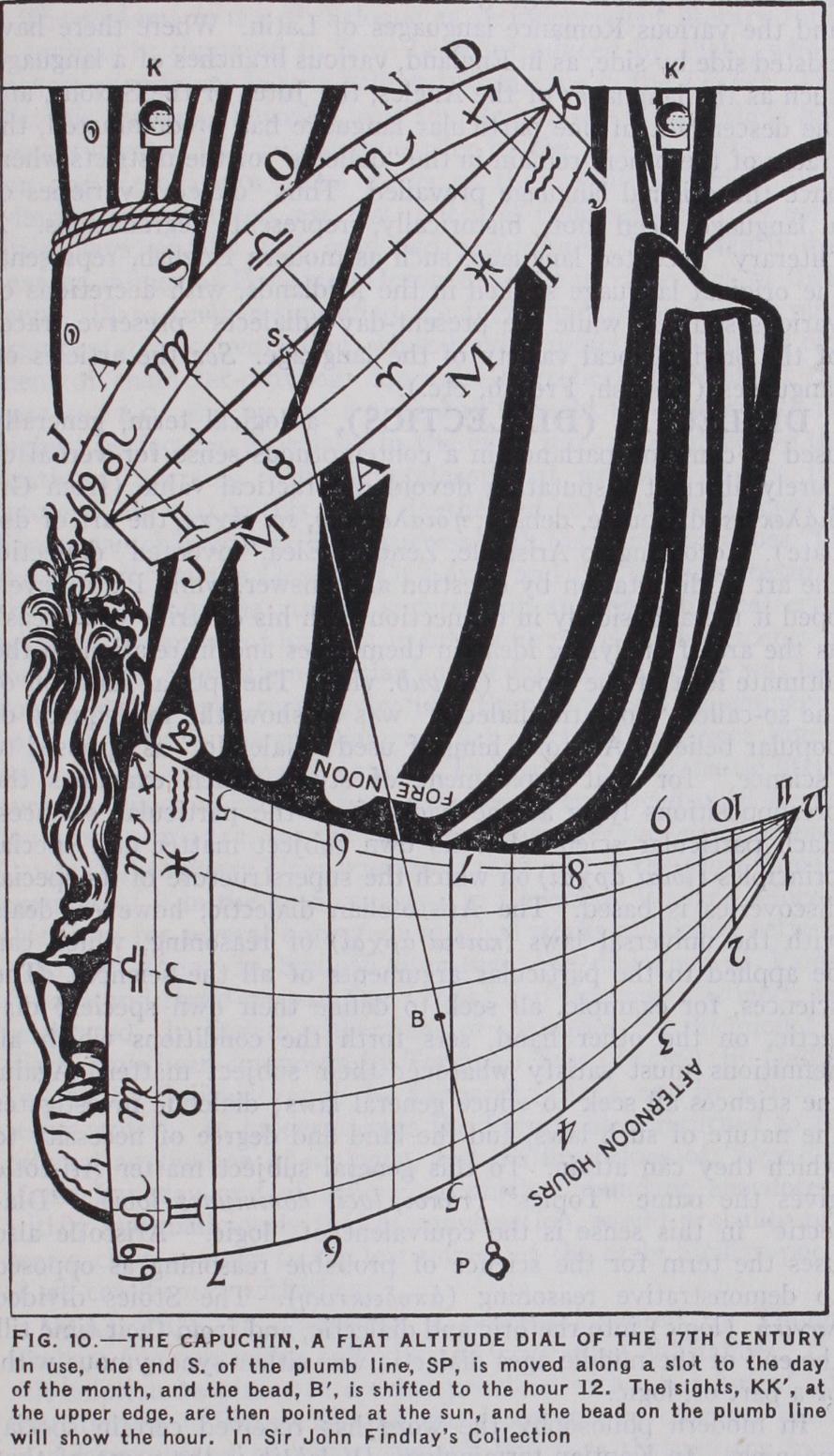

A very neat and ingenious flat altitude dial on a Card is attrib uated by Ozanam to a Jesuit Father, De Saint Rigaud, but it dates from the time of Regiomon tanus. It was sometimes called the capuchin, from some fancied re semblance to a cowl thrown back. Other altitude dials are the Quadrant dials, Ring dials, and Universal Ring dials. The Ring dial consists of a ring of brass that can be suspended by a small loop. A second, sliding ring within the first is drilled with a conical hole, with its apex to wards the inside. When the sun's rays pass through this hole they make a spot of light upon the op posite inner surface of the ring, which is divided by hour lines. The time can thus be read off.

The sliding ring is for adjustment for the latitude of the place, and the hour lines run diagonally for correction for the season of the year.

In the Universal Astronomical Ring dial a metal ring represents the meridian, and is suspended by a small ring and shackle ad justable for latitude. Pivoted to the meridian ring, so that it will fold within it when not in use, is a second or equatorial ring, divided into the 24 hours. On the line of the polar axis is a flat metal plate with a longitudinal slot, in which slides a block with a pinhole in it. This being adjusted for the sun's declination by means of a scale on the plate, and the instru ment suspended with its meridian circle in the meridian, the rays of the sun passing through the pin hole will fall on the hour of the equatorial circle.

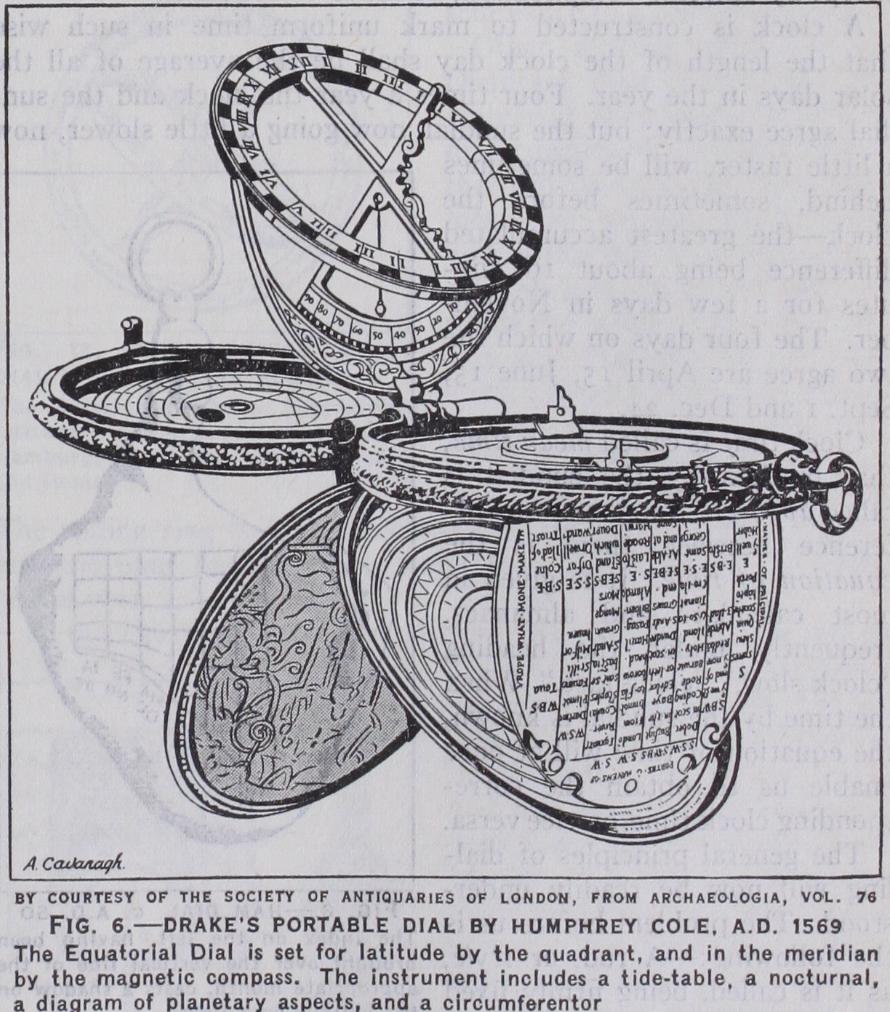

II. Compass Dials made their appearance in the 15th century, some 15o years after the description of the magnetic compass by Peter Peregrinus. In their simplest form they consist merely of a horizontal dial and a compass; but to these numerous acces sories were added in rapid succession, the most important being an adjustment for change of latitude, a plummet for levelling, subsid iary vertical and other dials for showing the various kinds of hours in use, a wind rose, volvelles for showing the phases of the moon or for use as adjustable calendars. These and other devices exer cised the ingenuity of the master craftsmen of Augsburg and Nuremberg, who vied with one another in the construction of a beautiful series of timepieces, which passed into all the coun tries of Europe. They were made of metal, wood, or ivory and the gnomons were either of metal or of a string that could be threaded through holes so as to vary the inclination with the latitude.

A second type of compass dial is the Equatorial dial, in which the plane of the dial is at right angles to the style and can be adjusted parallel to the equator. It is the simplest of all dials. A circle, divided into 24 equal arcs, is placed at right angles to the style, and hour divisions are marked upon it. Then, if care be taken that the style point ac curately to the pole and that the noon division lies in the meridian plane, the shadow of the style will fall on the other divisions, each at its proper time. The divi sions must be marked on both sides of the dial, because the sun will shine on opposite sides in the summer and in winter.

Equatorial dials were very widely used in the i7th and r8th centuries and were sometimes combined with geared clock movements, by which the hour and minute could be read on a clock face.

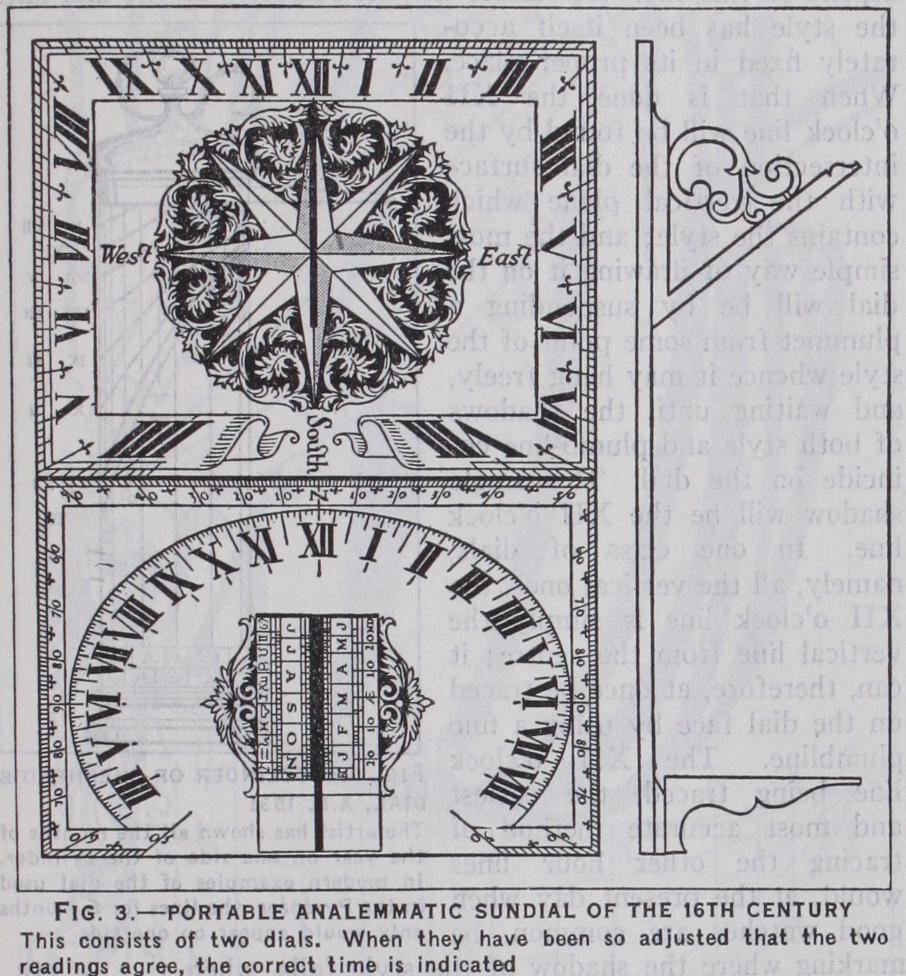

The Analemmatic Sundial dif fers from other portable sundials in that it can be set for finding the time without a compass. It in cludes two dials, an ordinary horizontal dial and an elliptical dial with a perpendicular gnomon which is set to the declination on a scale of months and days engraved along the minor axis of the ellipse. In use, the two styles cast two shadows on their respective hour scales. The instrument is then turned about until the two readings agree; when this happens the hour indicated is the cor rect time and the central line is true north and south.

Nocturnals were dials used for finding time by certain cir cumpolar stars.