Diet

DIET, a term used in two senses, (I) food or the regulation of feeding (see DIET AND DIETETICS), (2) an assembly or council. We are only concerned here with this second sense, and in particular with the diet of the Holy Roman empire and its relation to its successors in modern Germany.

The origin of the diet, or deliberative assembly, of the Holy Roman empire must be sought in the placitum of the Frankish empire. This represented the tribal assembly of the Franks, meeting partly for a military review on the eve of the summer campaign, partly for deliberation on important matters of politics and justice. By the side of this larger assembly, however, which contained in theory, if not in practice, the whole body of Franks, available for war, there had developed, even before Carolingian times, a smaller body composed of the magnates of the empire, both lay and ecclesiastical. The germ of this smaller body is to be found in the episcopal synods, which, afforced by the attend ance of lay magnates, came to be used by the king for the settle ment of national affairs. It is from this assembly of magnates that the diet of mediaeval Germany springs. The general assem bly became meaningless and unnecesary, as the feudal array gradually superseded the old levy en masse, in which each free man had been liable to service; and after the close of the i oth century it no longer existed.

The imperial diet (reic/istag) of the middle ages might some times contain representatives of Italy; but it was practically always confined to the magnates of Germany. The regular mem bers were the princes (Fiffrsten), both lay and ecclesiastical. In the i3th century the seven electors began to disengage themselves from the princes as a separate element; and the Golden Bull (1356) made their separation complete; from the i 4th century onwards the nobles (both counts and other lords) attend along with the princes; and after 125o the imperial and episcopal towns often appear through their representatives. By the 14th century, therefore, the originally homogeneous diet of princes is already, in practice, if not yet in legal form, divided into three colleges— the electors, the princes and nobles, and the representatives of the towns (though as we shall see, the latter can hardly be reckoned as regular members until the century of the Reforma tion). The powers of the diet during the middle ages extended to matters such as legislation, the decision upon military expe ditions (especially the expeditio Romana), taxation and changes in the constitution of the principalities or the empire. The elec tion of the king which was originally regarded as one of the powers of the diet, had passed to the electors by the middle of the 13th century.

A new era in the history of the diet begins with the Reforma tion. The division of the diet into three colleges was henceforth definite and precise. The representatives of the towns became regular members; but it was not until 1648 that they were recognized as equal to the other estates of the diet. The estate of the princes and counts, which stood midway between the elec tors and the towns, also attained, in the years that followed the Reformation, its final organization. The vote of the great princes ceased to be personal and began to be territorial: it was not the status of princely rank, but the possession of a principality which was henceforward a title to membership. The position of the counts and other lords, who joined with the princes in forming the middle estate, was also finally fixed by the middle of the 1 7th cen tury. While each of the princes enjoyed an individual vote, the counts and other lords were arranged in groups, each of which voted as a whole, though the whole of its vote (Kurialstimme) only counted as equal to the vote of a single prince (Virilstimme).

There were six of these groups ; but as the votes of the whole college of princes and counts (at any rate in the i8th century) numbered 1 oo, they could exercise but little weight.

The last era in the history of the diet may be said to open with the treaty of Westphalia (1648). The treaty acknowledged that Germany was no longer a unitary State, but a loose confedera tion of sovereign princes; and the diet accordingly ceased to bear the character of a national assembly, and became a mere congress of envoys. The last diet which issued a regular "recess" (reichsabschied—the term applied to the acta of the diet, as formally compiled and enunciated at its dissolution) was that of Regensburg in 1654. The next diet, which met at Regensburg in 1663, never issued a recess, and was never dissolved; it continued in permanent session, as it were, till the dissolution of the empire in 1806. This result was achieved by the process of turning the diet from an assembly of principals into, a congress of envoys. The emperor was represented by two commissarii; the electors, princes and towns were similarly represented by their accredited agents. In practice the diet had nothing to do; and its members occupied themselves in "wrangling about chairs"—that is to say, in unending disputes about rights of precedence.

In the Germanic Confederation, which occupies the interval between the death of the Holy Roman empire and the formation of the North German Confederation (1815-66), a diet (Bundes tag) existed, which was modelled on the old diet of the 18th century. It was a standing congress of envoys at Frankfurt-on Main. In the North German Confederation (1867-7o) a new departure was made, which was followed in the constitution of the German empire after 187o. Two bodies were instituted—a bundesrat, which resembled the old diet in being a congress of envoys sent by the different States of the confederation, and a reiclistag, which bore the name of the old diet, but differed en tirely in composition. The new reichstag was a popular representa tive assembly, based on wide suffrage and elected by ballot ; and, above all, it was an assembly representing, not the several States, but the whole empire, which was divided for this purpose into electoral districts. Both as a popular assembly, and as an assem bly which represents the whole of a united Germany, the reichstag of modern Germany goes back, one may almost say, beyond the diet even of the middle ages, to the days of the old Teutonic f olk-moot.

See R. Schroder, Lehrbuch der deutschen Rechtsgeschichte (19oz) , PP. 149, Sob, 82o, 880. Schroder gives a bibliography of monographs bearing on the history of the mediaeval diet. (E. B.) DIET and DIETETICS, that part of science which deals with food, its composition and its value to the animal economy in supplying the necessary material for life and work.

Food may be defined as that which when taken into the body

may be utilized for the formation and repair of body tissues and for the production of energy. When a living being is increasing in size, materials must obviously be supplied for the purpose, and the food must contain in some form the actual chemical constitu ents of the new tissues which are being laid down. Even in the adult the various parts of the body undergo wear and tear just as any machine does and this loss of substance must be replaced from the food.

It is not necessary that all the chemical compounds which are

found in the body shall be present in the food ; but the necessary chemical elements and certain complex groupings must be pro vided from which the body can build up what it needs. Only a small part of the ingested food is made use of for purposes of growth or replacement ; most of it is needed for the liberation of energy to perform muscular and glandular work, and partly for conversion into heat. The law of conservation of energy has been found to apply to man and animals as well as to inanimate nature; the income and expenditure of energy in the body are equal.

The energy value of foodstuffs is universally expressed in terms

of heat units or calories (referred to in this article as C.). The calorie (C.) is the quantity of heat energy required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of water by I ° Centigrade. The total energy that can be obtained from food is determined by burning a known weight of foodstuff in oxygen and measuring the amount of heat produced by the combustion.

Essential Constituents.

The essential constituents of a diet are proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, water and salts. Proteins are complex bodies containing the elements C, H, 0, N, and sometimes P, S, and Fe. They are the only constituents of the diet which contain nitrogen in a form which may be used for pur poses of body building or of repair. The albumen of egg white, vitellin of egg yolk, myosin of meat, casein of milk and glutein of flour are examples. Meat extract, soups and beef tea have practi cally no energy value though they probably improve the appetite and increase the flow of the digestive juices.Fats are compounds of glycerin with acids containing a large number of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms and afford much energy when burnt. Butter, lard, suet, olive oil are examples of nearly pure fats, but fat is a constituent of most natural foodstuffs in varying quantity.

Carbohydrates contain carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, the two latter elements being present in the same proportions as they are in water. They are met in a variety of forms—starch, a prominent constituent of wheat and other cereals and potatoes; sugar, of which several kinds are distinguished ; e.g., cane sugar of sugar cane and beetroot, milk sugar or lactose of milk, glucose and fructose in fruits and honey.

These three kinds of foodstuffs yield energy on being oxidized

in the body, so that in a diet they may be replaced one by the other to a considerable extent. But we shall see that certain mini mal amounts of the individual foodstuffs are essential if health and growth are to be maintained. The accepted values for the energy liberated by igm. of each of the foodstuffs when burnt in the body are as follows :—Protein 4.1 C.; carbohydrate 4.1 C.; fat 9.3 C. If protein is completely combusted outside the body it yields 5.6 C. per I gm. The destruction of protein in the body is, however, not so complete, as a certain number of products are excreted in the urine which are capable of still further oxidation and liberation of energy.

Basal Metabolism.

For a first calculation it is desirable to determine the total food requirements in terms of calorie value, for we have to provide sufficient energy to meet individual needs. Living matter is continually undergoing chemical changes and as a result of these activities energy is being liberated. This process is taking place on a considerable scale even when the body is under conditions of complete physical and mental rest. The amount of energy evolved is found to be correlated most closely with the surface area and less closely with the body weight.

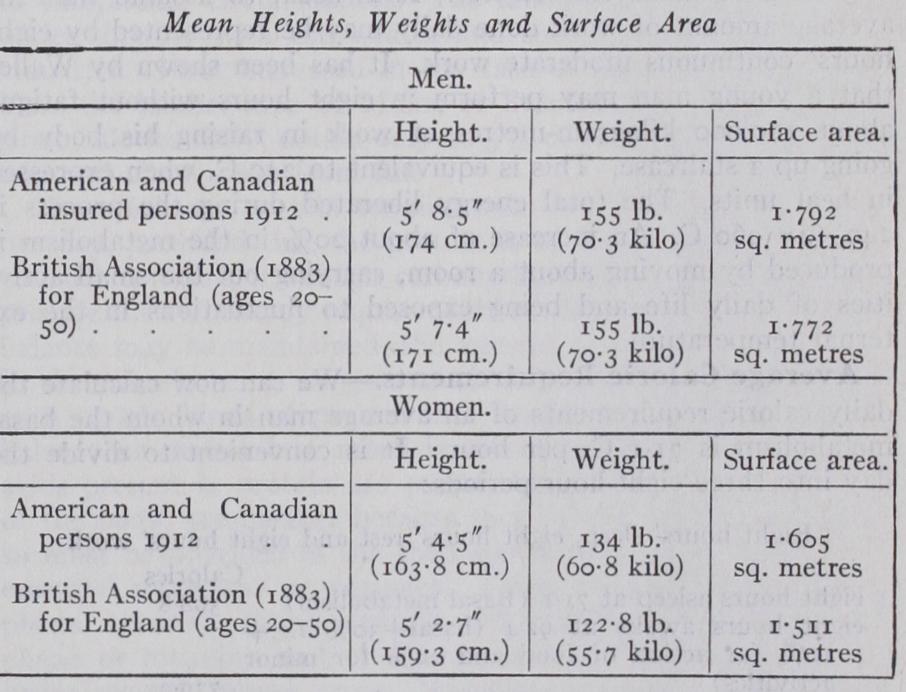

It is found desirable for comparative purposes to determine the

energy output first under so-called basal conditions—namely at complete bodily rest after the digestion and absorption of the last meal has been completed. In adult males the energy liberated un der such conditions (basal metabolism) is 4o C. per sq. metre of body surface per hour or less accurately i C. per kg. body weight per hour. The surface area can be calculated from du Bois' formula S = .007 I 84 X X H° where S is the surface in sq. metre, W the weight in kilograms and H the height in centimetres. In females the metabolic processes are slightly less active and only amount to 37 C. per sq. metre per hour.

The weights quoted are with the clothes on; io lb. has been

subtracted from them before compiling the surface area to allow for the weight of the clothes.

The English figures are old, but have recently been confirmed

for nearly 5,00o working women. An English adult with a surface area of 1.772 sq. metre would have a basal metabolism of 1 • 7 7 2 X 40 C. per hr. or 17o I C. per 24 hours. The basal metabolism di minishes slightly as age advances, so that the resting energy re quirements of the old are less than those of young adults. This large resting energy output is devoted to a small extent to maintain the activity of the vital organs—to enable the heart, the brain, the respiratory muscles and the essential glands to continue their functions ; but in the main the energy is converted into heat and used to maintain the normal temperature of the body.The basal metabolism is altered by changes of external temper ature. On exposure to cold, metabolism is stimulated, chiefly by increased muscular activity; on exposure to heat, it is somewhat surprising to find that there is little depression of the metabolism. Immediate compensation is established by sweating and flushing the skin with blood. In the tropics, however, it has been shown by de Almeida that the metabolic rate is about 2 5 % lower than it is in the temperate zone, and food requirements would be cor respondingly diminished. A rise of i ° F. in body temperature causes an increase of 7% in the metabolism, so that a patient with a temperature of i os ° F. would have a metabolic rate which is so% above normal.

Prolonged under-nutrition results in a great lowering of the resting metabolism and this may be regarded as a protective re action on the part of the tissues to the unfavourable environment. The ingestion of food results in an increase in metabolism; this is mainly due to the stimulating action exerted by the prod ucts of digestion on the tissue cells. This effect varies with the kind of food consumed, and is more marked with protein than with fats or carbohydrates. This property of protein is referred to as its "specific dynamic action" and is due to the action of the amino acids of which it is composed, more especially glycine and alanine. It is difficult to see what advantage is conferred on the body by the specific dynamic action of protein; it gives rise to a wasteful expenditure of energy quite independently of the needs of the body. The effect of an ordinary mixed diet is to increase the daily metabolism by about io%.

Finally energy is needed for the carrying out of physical work. It is difficult to compute the energy expended during ordinary body movements and in the various avocations. It must be re membered that the mechanical efficiency of the body is about 25%; by this is meant that only 25% of the energy freed as a result of the chemical transformation in the muscles is converted into work and the remaining 75% is dissipated as heat. Conse quently if the energy value of the work done is expressed in heat units, this figure must be multiplied by four to obtain the amount of energy liberated in the body during the process. An example may help to make this clearer. It is usual to assume that the average amount of work done daily may be represented by eight hours' continuous moderate work. It has been shown by Waller that a young man may perform in eight hours without fatigue about 100,00o kilogram-metres of work in raising his body by going up a staircase. This is equivalent to 240 C. when expressed in heat units. The total energy liberated during the process is C. An increase of about 20% in the metabolism is produced by moving about a room, carrying out the small activ ities of daily life and being exposed to fluctuations in the ex ternal temperature.

Average Calorie Requirements.

We can now calculate the daily calorie requirements of an average man in whom the basal metabolism is 71•1 C. per hour. It is convenient to divide the day into three eight-hour periods: Eight hours' sleep, eight hours' rest and eight hours' work Calories eight hours asleep at 71•1 (Basal metabolism) . 568.8 eight hours awake at 92.4 (basal-1-3o% i.e.+ io% for action of food and 20% for minor activities) 739.2 eight hours' work (basal+96o C.) . . . 1,528.8 Total . . . . . . . 2,83 6.8 Add for locomotion and travelling . . . 300 3,136.8 (Starling) In the above-given estimate an allowance had been made for the energy expended in travelling between home and place of occupa tion. The Food (War) Committee of the Royal Society suggested that the various occupations should be classified as follows as far as the energy requirements for the work are covered:— Sedentary: less than 400 C. in excess of resting requirements. Light work : 40o to 700 C. in excess of resting requirements. Moderate work: 700-1,100 C. in excess of resting requirements. Heavy work: 1,100--2,000 C. in excess of resting requirements.Among the sedentary pursuits must be included all classes of brain worker. Even the most intense mental activity causes no appreciable increase in the metabolism. In a country like Great Britain determinations of the total energy expended by different classes of workers have shown that the average is about 3,00o C. per diem. A distinction must be drawn between the energy value of the digested food and of the food as purchased. A small per centage of the food escapes digestion and absorption and is elim inated in the faces; this is more marked on a vegetable than on an animal diet. It is usual to deduct 1 o% from the theoretical calorie value of the mixed diet to allow for this loss. Thus if 3,00o C. are needed by the body, the daily ration should contain C. and this represents a fair average allowance for each adult male of the population. The energy requirements of work ing women can be similarly calculated and found to be about 2,20o C. A net allowance of 2,400 C. would be ample and leave an adequate surplus for household duties. The calorie value of the food as purchased should be 2,65o C. The food requirements of a purely sedentary worker should not exceed 2,100 C.

Calorie Needs of Children.

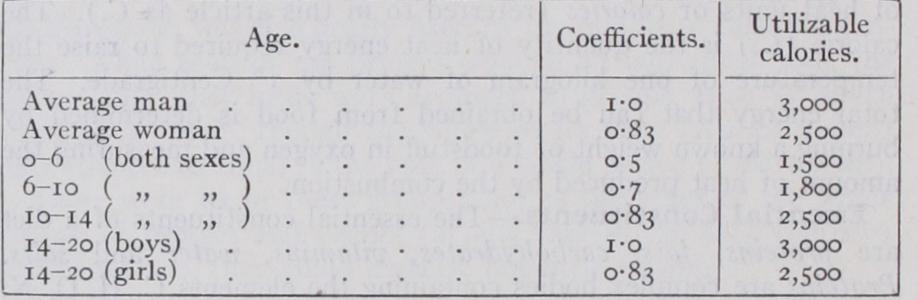

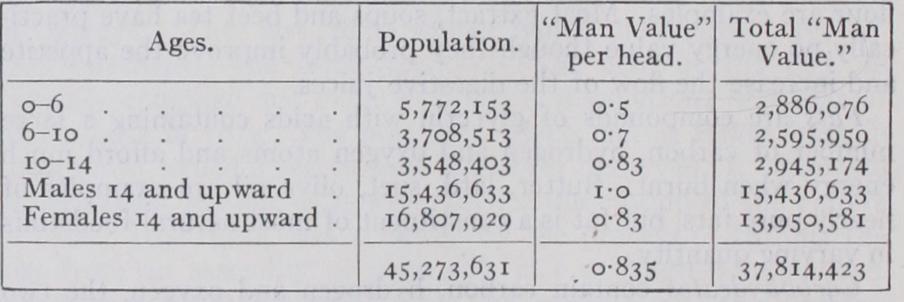

The energy needs of children are extremely difficult to compute. The basal metabolism in children per square metre of body surface per hour is considerably higher than in adults; e.g. age 6, 57-5 C.; age 12.6, 50-4 C. ; age C.; age 43.0 C.; age 20.25, 40.7 C. (du Bois). Greenwood has calculated from the scanty data available the basal requirements in calories of boys and girls.Age 5 6 7 8 9 Boys . . . IO26 I I00 1159 I 197 1262 Girls . . . Ioo8 1057 III0 1163 1201 Age Io II I2 13 14 Boys . . . 1328 1358 1389 Girls . . . 2266 1321 1539 The fact that growth is occurring implies that excess of energy must be taken over and above that required to furnish the energy output of the body. Between the ages of II and 16 both sexes put on weight at the average rate of about 4 kilos a year. This is equivalent to only 3o C. per day; but the growing body is formed at the expense of many different varieties of food which have to undergo chemical conversions of different kinds before they can take their place as part of the living body, so that prob ably the amount of energy which must be provided in the food to produce the necessary increase in weight is considerably in excess of 3o C. It is very difficult to compute the energy output due to muscular activity in children. Lusk gives the following table to show the food requirements of children in relation to that of an average man or woman : Average and Total "Man Value."—By using these coeffi cients we can determine the "average and total man value" of a mixed population.

The table quoted from Starling shows the calculation made for 1911 population of the United Kingdom. Allowing 3,30o C. per man per day, the total requirements of the whole population would amount to approximately 45.5 billion calories. It is interest ing to note that the average annual requirements per head are 1,200,000 C. A computation has been made of the calorie value of the food available for consumption in the United Kingdom during the years 1909-13. It amounted to just over 47 billion calories, which gave a daily ration of 3,410 C. per "average man." In France, according to official statistics, the average consumption per man per day before the war was 3,80o C. ; in 1916-17, C. ; in 2,900 C. Some small addition must be added to these figures for the calorie value of cottage and garden production which cannot be determined accurately. The average energy con sumption per head for all countries is 3,400 C.

World's Calorie Requirements.

Holmes has presented data to show the amount of energy contributed annually to the world's requirements by the more important food materials. Expressed in trillion calories the figures are :—Rice goo, wheat 382, sugar 2o9, rye 164, barley 119, potatoes 99, meat 62. The figures show clearly how dependent mankind is on cereals for the major part of its energy needs. The consumption of meat is concentrated in relatively few countries. No data are available for China, India or Japan where the amount used is known to be small. The highest figures are those of the meat raising countries, Australia, Argentine and the U.S.A. where the number of lb. of meat and meat prod ucts consumed per head annually are 262.6, i4o and 171 lb. respectively. In Great Britain the figure is 119 lb. and in Por tugal only 44 lb.If the diet of many nations is surveyed, it is found that meat, including fish, poultry and eggs, supplies 2o% of the calories and about the same percentage of the protein; milk and its products 13-17% of the calories and 14-25% of the protein; cereals 35-4o% of both calories and protein. The greatest variation is found in the nature of the cereal used. In Great Britain and France it is almost exclusively wheat; in U.S.A. maize is not unimportant ; in Germany especially among the rural population, rye is used almost exclusively. The part played by sugar is greatest in Great Britain and the U.S.A. but is considerable in all countries. Potatoes usually furnish 0-12% of the total energy needs and a somewhat smaller part of the protein.