Etc Dry Docks

DRY DOCKS, ETC.

Provision has often to be made at ports for the repairs of ves sels frequenting them. The primitive method of effecting repairs and cleaning was by careening the vessel or by beaching.

The simplest structure designed for the purpose of effecting minor under-water repairs and cleaning is the gridiron, still em ployed in some ports, where the tidal rise is suitable, for vessels of moderate size. It is a level platform of timber beams, con structed on a firm foundation, on which the ship settles with a failing tide and can then be inspected at low water.

Slipways.

Inclined slipways, up which a vessel of moderate size, resting in a cradle on wheels, can be drawn out of the water above the reach of the tide for cleaning or repairs, are used in many ports in all parts of the world. The foundations for the rails on which the cradle travels must be firm and unyielding. The rails are laid at gradients which vary from i in 15 to in 25, the usual slope being about 1 in 20. The contrivance was patented by Thomas Morton of Leith, in 1818. He constructed many "patent slips," as they are often called, in European ports. Hydraulic haul ing machines were first used for slipways about 185o. Previous to that time horses or steam engines and gearing were used. In modern examples electric hauling gear is frequently employed. A few slipways have been constructed to haul up ships broadside on, the cradle being borne on a series of transverse rails instead of on rails laid parallel with the centre line of the ship which is the usual practice. Slipways have been built in Europe to take vessels displacing up to about 4,500 tons; but in North American waters there are examples having a still larger capacity.

Slip-docks.

When the vessel is partially withdrawn from the water by means of a cradle on ways and the tide is excluded from the upper part of the slipway by a pair of gates and side walls, thus effecting an economy in its length, the arrangement is called a slip-dock. They are, however, rare in modern ports.

Dry Docks.

A dry dock is the usual means provided for en abling the cleaning and repairing of vessels to be carried out (v. supra for early examples). Dry docks are sometimes known as graving docks but the former term is now more often used in British ports. The word "graving" originally denoted the cleaning less time in opening and closing. They necessitate a longer lock or entrance passage than caissons because of the space required for the gate recesses; but, on the other hand, a sliding or rolling caisson requires a long camber at the side of the entrance. Cais sons are somewhat more costly than gates, but they can conveni ently be made to afford accommodation for rail and road traffic across an entrance and thus obviate the necessity of a swing bridge in some cases. Moreover, they can be constructed to take water pressure on both sides, thus doing the work of two pairs of gates. An instance of this is the new lock at Ymuiden. Where of a ship's bottom by scraping or burning, and coating with tar.A dry dock is a narrow basin, closed by gates or by a caisson, in which a vessel may be placed and from which the water may be pumped or let out, leaving the vessel dry and supported on blocks. A dry dock is sometimes used, especially in naval dock yards, for building ships. Many old dry docks were built of timber, and there are several such still in use in the port of London. In the United States timber dry docks are in common use even for large vessels. The typical modern dry dock, however, consists of concrete side walls, resembling those of a lock, but stepped back towards the top, with a substantial concrete floor upon which the keel blocks, and sometimes bilge blocks also, rest (figs. 26 and 27). The floor usually has a slight fall from back to front, and from the centre to the sides, to facilitate drainage.

Dry docks should, for preference, be founded on a solid im pervious stratum, but this is not always possible. It is often impracticable to obviate the presence under the dock bottom of water which may exert a hydrostatic upward pressure when the dock is pumped out. Such conditions are usually met in one or other of two ways. The floor may be made comparatively thin with vents formed in it or low down in the side walls to relieve the pressure of the water which is allowed to leak into the dock and is dealt with by drainage pumps. The alternative is to make the dock floor and walls of sufficient weight and dimensions to resist the maximum pressure due to saturation of the surrounding soil. That is to say, the floor must act as an inverted arch and the whole body of the dock when empty must be of sufficient weight to resist the tendency to flotation. In bad ground and when the floor is thin, bearing piles are often driven under the dock floor in way of the keel blocks, and, in some cases, under the whole of the floor and side walls also. In any case the floor must be of sufficient strength to bear the weight of the heaviest ship which the dock can take in, concentrated on the lines of the supporting blocks. Thus far very few dry docks have been built of reinforced concrete, forming a rigid box, usually supported on piling.

A dry dock at Havre (see table III.) , opened in 1927, is of par ticular interest on account of the method adopted for its con struction on a deep stratum of sand and silt. The entire dock structure was built in and upon a huge steel caisson framework 1,132 x 197ft. which was floated into position over the site of the dock, previously dredged to the required depth, and there sunk in place. The caisson was constructed on levelled ground within a containing embankment and portions of the floor and side walls were built in it before it was floated out to the permanent site.

The stepped courses provided in the upper parts of the side walls of a dry dock are called "altars" and are used for the support of- side shores between them and the ship. Culverts, controlled by sluice gates (fig. 20), are built in the side walls of the entrance for flooding the dock when it is necessary to let a ship out. Centrifugal pumps—usually electrically driven in modern docks— are employed for pumping out the dock and maintaining effective drainage. The water flows to the pump sump chamber and from the pumps to the outside of the dry dock through culverts. (See figs. 26 and 27). In many old docks, in positions where the tidal range is suitable, water is run out as the tide falls; but in modern practice it is customary to provide for pumping out the whole of the water in about 3 hours—more or less.

In ports where the tidal rise is considerable and there are wet docks, it is preferable, when practicable, to construct a dry dock with its entrance from within the wet dock and not from the tide way. There are many advantages attending this arrangement: still water for manoeuvring the ship ; availability for use at all states of the tide; and comparative freedom from siltation may be instanced. In situations where a dry dock is entered from tidal water of considerable range, it is desirable to provide for holding up the water inside the dock above the level of the falling tide in order that ample time shall always be available for shoring and other dock operations.

Equipment of Dry Docks.—The machinery employed at dry docks for working gates, caissons, sluices and capstans is generally on the same lines as for entrance locks. It is necessary, however, to equip a dry dock, in addition to the pumps already referred to, with powerful cranes, travelling along the dock side, to deal with the heavy lifts sometimes necessary in effecting ship repairs (see fig. 27). As an example of such provision the Trafalgar dry dock at Southampton has an electric travelling portal crane lifting 5o tons at a radius of 87ft. Most of the modern dry docks thus far constructed are also well equipped for working electric and compressed air tools.

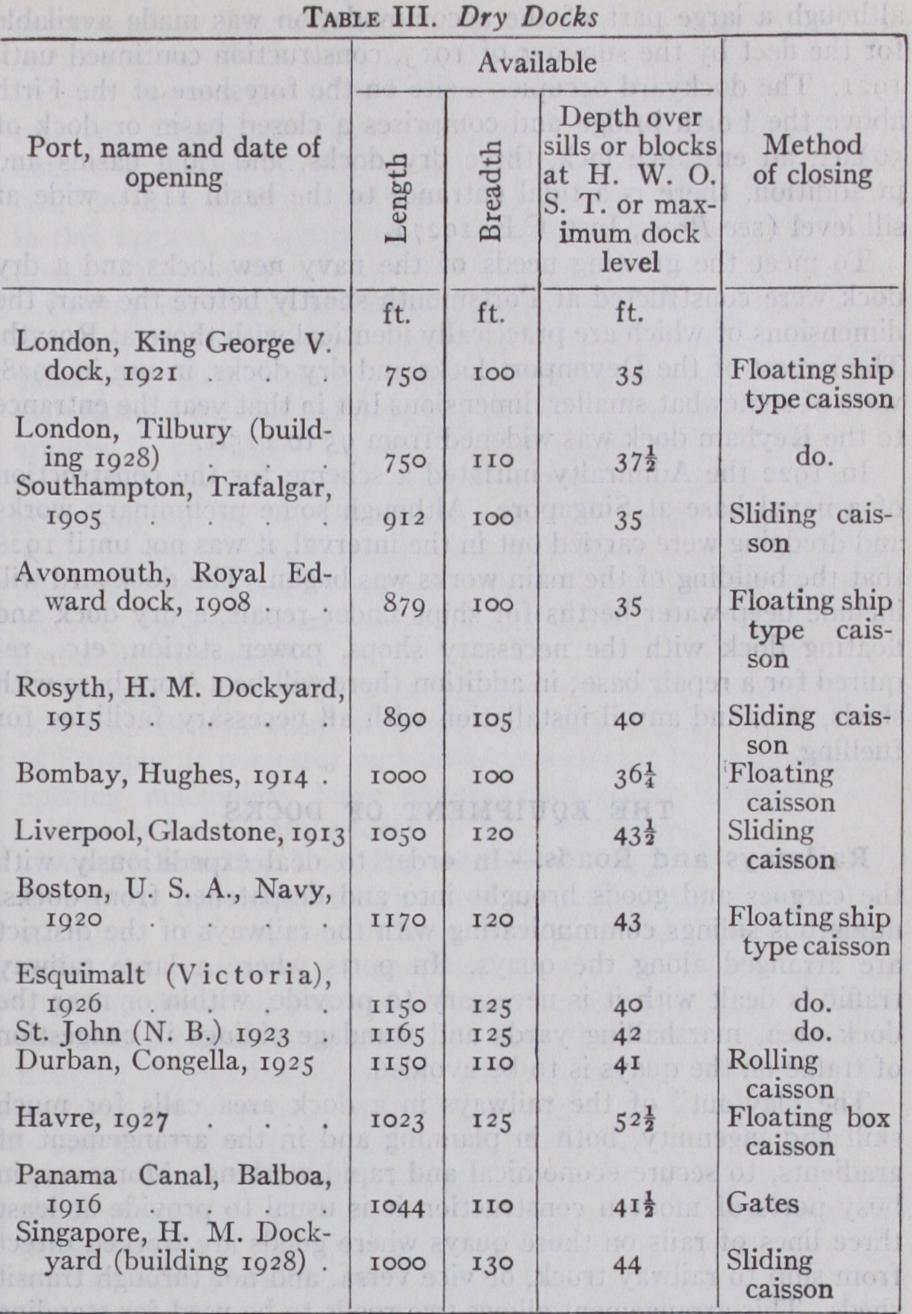

Examples of Dry Docks.

The following table (III.) gives particulars of some typical large modern dry docks :— Floating Docks.—Floating dry docks are used in some situa tions where there is no site available for an ordinary dry dock or where special conditions render the floating structure more con venient or economical. They possess the advantage of mobility and, during the World War, large floating docks were moved from ports where they were not urgently needed to places such as the Tyne and Cromarty firth where they could be more usefully em ployed. It is only necessary to find a sheltered site, with a suf ficient depth of water, for conducting the operations of a floating dock. But, although a floating dock may be self-contained with workshops in its walls, or be served by a separate floating work shop, experience shows that to obtain the full advantage it is advisable to have an establishment on shore. This tends to restrict the choice of site. Furthermore, a floating dock can often be built and placed in service in a fraction of the time which would be necessary to construct an ordinary dry dock. The largest float ing dock in the world (1928) is that at Southampton completed in 1924. It has an overall length of 86of t. ; clear inside width of 13oif t. ; and a total lifting power of 6o,000 tons. The dock can be submerged to take in ships drawing 38ft., and the berth where it is moored is dredged to a depth of 61ft. at L.W.O.S.T. It has docked the largest ship afloat (see Proc., Inst. C.E. 1925).

Unfortunately the dredging of such deep pits below the general level of the harbour bed as are required in some situations for a floating dock of very large dimensions is sometimes followed by rapid silting and this has occurred at Southampton where redredg ing has been necessary at intervals of less than 2 years.