Anatomy of Ear

EAR, ANATOMY OF. The human ear is divided into three parts—external, middle and internal. The external ear con sists of the pinna and the external auditory meatus. The pinna is composed of yellow fibro-cartilage covered by skin. Round the margin in its upper three-quarters is a rim called the helix (fig. 1), in which is often seen a little prominence known as Dar win's tubercle, representing the folded-over apex of a prick-eared ancestor. Concentric with the helix and nearer the meatus is the antihelix which, above, divides into two limbs. In front of the antihelix is the deep fossa known as the concha (fig. I), and from the anterior part of this the meatus passes inward into the skull. Overlapping the meatus from in front is a flap called the tragus, and below and behind this is another smaller flap, the antitragus. The lower part of the pinna is the lobule, which contains no cartilage. The pinna can be slightly moved by the anterior, superior and posterior auricular muscles. The external auditory meatus (fig. 1) is a tube about an inch long, its outer third being cartilaginous and its inner two-thirds bony. It is lined by skin in its whole length, the sweat glands of which are modified to secrete the wax or cerumen. Internally it is closed by the tympanic membrane.

The middle ear or tympanum (fig. 1) is a small cavity in the temporal bone. The Eustachian tube runs thence forward, inward and downward, to open into the nasopharynx, and so admits air into the tympanum. From the upper part of the posterior wall of the tympanum, an opening leads backward into the mastoid antrum and so into the air-cells of the mastoid process. Lower down is a little pyramid which transmits the stapedius muscle, and at the base of this is a small opening for the chorda tympani to come through from the facial nerve. The roof is formed by a very thin plate of bone, which separates the cavity from the middle fossa of the skull. Below the roof the upper part of the tympanum is somewhat constricted off from the rest, and to this part the term "attic" is often applied. The floor is a mere groove formed by the meeting of the external and internal walls. The outer wall is largely occupied by the tympanic membrane (fig. 1), which entirely separates the middle ear from the external audi tory meatus ; it is circular, and so placed that it slopes from above, downward and inward, and from behind, forward and in ward. Externally it is lined by skin, internally by mucous mem brane, while between the two is a firm fibrous membrane, convex inward about its centre to form the umbo.

The inner wall shows a promontory caused by the cochlea and grooved by the tympanic plexus of nerves; above and behind it is the fenestra ovalis, while below and behind the fenestra rotunda is seen, closed by a membrane. Curving round, above and behind the promontory and fenestrae, is a ridge caused by the aqueductus Fallopii or canal for the facial nerve. The whole tympanum is about half an inch from before backward, and half an inch high, and is spanned from side to side by three small bones, of which the malleus is external. This is attached by its handle to the umbo of the tympanic membrane, while its head lies in the attic and articulates posteriorly with the upper part of the next bone or incus. The long process of the incus runs downward and ends in a little knob, the os orbiculare, jointed on to the stapes or stir rup bone. The two branches of the stapes are anterior and posterior, while the footplate fits into the fenestra ovalis and is bound to it by a membrane. It will thus be seen that the stapes lies nearly at right angles to the long process of the incus. Bony processes of the malleus and incus articulating respectively with the anterior and posterior walls of the tympanum form a fulcrum by which the lever action of the malleus and incus is brought about, so that when the handle of the malleus is pushed in by the membrane the head moves out ; the top of the incus, attached to it, also moves out, and the os orbiculare moves in, and so the stapes is pressed into the fenestra ovalis. The stapedius and tensor tym panic muscles modify the movements of the ossicles.

The mucous membrane lining the tympanum is continuous through the Eustachian tube with that of the naso-pharynx, and is reflected on to the ossicles, muscles and chorda tympani nerve. It is ciliated except where it covers the membrana tympani, ossicles and promontory; here it is stratified.

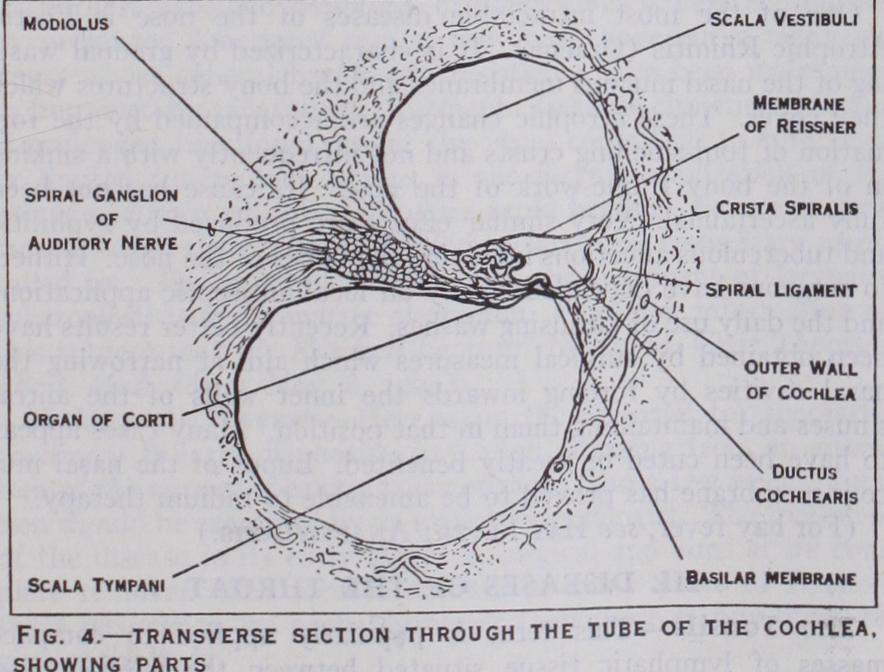

The internal ear or labyrinth consists of a bony and a mem branous part, the latter of which is contained in the former. The bony labyrinth is composed of the vestibule, the semi-circular canals and the cochlea. The vestibule lies just internal to the posterior part of the tympanum, and there would be a communi cation between the two, through the fenestra ovalis, were it not that the foot—plate of the stapes blocks the way. The inner wall of the vestibule is separated from the bottom of the internal auditory meatus by a plate of bone pierced by many foramina for branches of the auditory nerve (fig. I), while at the lower part is the opening of the aqueductus vestibuli, by means of which a communication is established with the posterior cranial fossa. Posteriorly the three semicircular canals open into the vestibule; of these the external has two independent openings, but the superior and posterior join together at one end, while at their other ends they open separately. One end of each canal is dilated to form its ampulla. The superior semicircular canal is vertical, and the two pillars of its arch are nearly external and internal; the external canal is horizontal, its two pillars being anterior and posterior, while the convexity of the arch of the posterior canal is backward and its two pillars are superior and inferior. An teriorly the vestibule leads into the cochlea (fig. i, 4) which is twisted two and half times round a central pillar called the modiolus, the whole cochlea forming a rounded cone something like the shell of a snail though it is only about 5mm. from base to apex. Projecting from the modiolus is a horizontal plate (lamina spiralis) which runs round it from base to apex like a spiral staircase ; it stretches nearly half-way across the canal of the cochlea and carries branches of the auditory nerve.

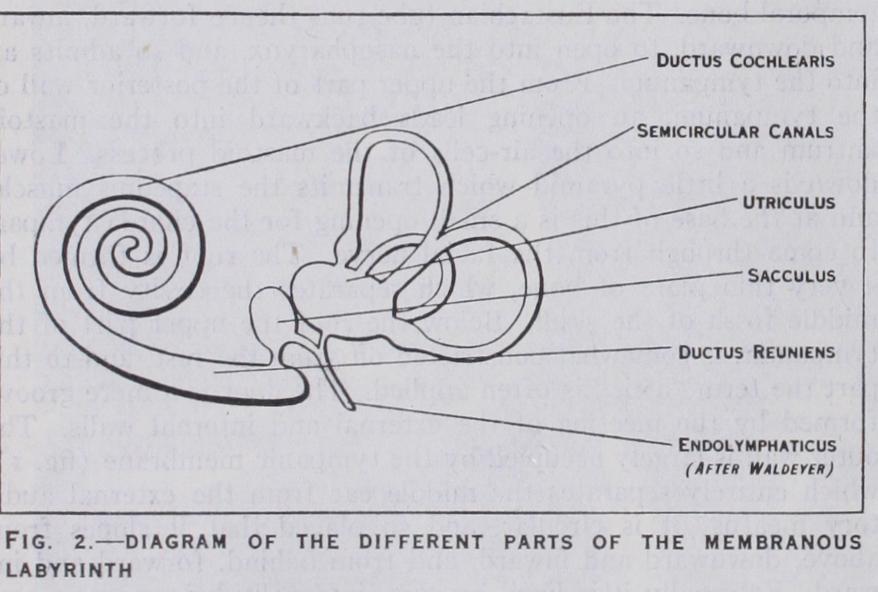

The membranous labyrinth lies in the bony labyrinth, but does not fill it; between the two is the fluid called perilymph, while in side the membranous labyrinth is the endolymph. In the bony vestibule lie two membranous bags, one of which, the saccule (fig. 2), is in front, and the other, the utricle, behind; each has a special patch or macula to which twigs of the auditory nerve are supplied, and in the mucous membrane of which are specialized hair cells (fig. 3) .

Attached to the maculae are crystals of carbonate of lime called otoconia. The membranous semicircular canals are very much smaller in section than the bony; in the ampulla of each is a ridge, the crista acustica, which is covered by a mucous mem brane containing sensory hair cells like those in the maculae.

All the canals open into the utricle. From the lower part of the saccule runs a small canal called the ductus endolymphati cus (fig. 2). Anteriorly the sac cule communicates with the mem branous cochlea or scala media by a short ductus reuniens. A sec tion obtained through each turn of the cochlea shows the bony lamina spiralis, already noticed, which is continued right across the canal by the basilar mem brane (fig. 4), thereby cutting the canal into an upper and lower half, and connected with the outer wall by the strong spiral liga ment. Near the free end of the lamina spiralis the membrane of Reissner is attached, and runs outward and upward to the outer wall, taking a triangular slice out of the upper half. There are now three canals seen in section; the upper is the scala vestibuli, the middle and outer scala media, ductus cochlearis or true membranous cochlea and the lower, the scala tympani. The scala vestibuli and scala tympani communicate at the apex of the cochlea, so that the perilymph can here pass from one canal to the other. At the base of the cochlea the peri lymph in the scala vestibuli is continuous with that in the vesti bule, but that in the scala tympani bathes the inner surface of the membrane stretched across the fenestra rotunda, and also commu nicates with the subarachnoid space through the aqueductus coch lea, which opens into the posterior cranial fossa. The scala media containing endolymph communicates with the saccule through the canalis reuniens, while, at the apex of the cochlea, it ends in a blind extremity of considerable morphological interest which is called the lagena.

The scala media contains the essential organ of hearing or organ of Corti (fig. 4), which lies upon the inner part of the basilar membrane ; it consists of a tunnel bounded on each side of the inner and outer rods of Corti; on each side of these are the inner and outer hair cells, between the latter of which are found the supporting cells of Deiters. Most externally are the large cells of Hensen. A delicate membrane called the lamina reticularis covers the top of all these, and is pierced by the hairs of the hair cells, while above this is the loose membrana tectoria attached to the periosteum of the lamina spiralis, near its tip, in ternally, and possibly to some of Deiters' cells externally. The cochlear branch of the auditory nerve enters the lamina spiralis, where a spiral ganglion (fig. 4) is developed on it; after this it is distributed to the inner and outer hair cells.

Embryology.

The pinna is formed from six tubercles which appear round the dorsal end of the hyomandibular cleft. Those for the tragus and anterior part of the helix belong to the first or mandibular arch, while those for the antitragus, antihelix and lobule come from the second or hyoid arch. The tubercle for the helix is dorsal to the end of the cleft where the two arches join. The external auditory meatus, tympanum and Eustachian tube are remains of the hyomandibular cleft, the membrana tympani being a remnant of the cleft membrane and therefore lined by ectoderm outside and entoderm inside. The origin of the ossicles is doubtful. H. Gadow's view is that alL three are derived from the hyomandibular plate. The internal ear first appears as a pit from the cephalic ectoderm, the mouth of which in mammals closes up, to leave a pear-shaped cavity. The lower part of the vesicle grows forward and becomes the cochlea, while from the upper part three hollow circular plates grow out, the central parts of which dis appear, leaving the margin as the semicircular canals. Subse quently constrictions appear in the vesicle marking off the saccule and utricle. From the surrounding mesoderm the petrous bone is formed by a process of chondrification and ossification.

Comparative Anatomy.

The ectodermal inpushing of the internal ear has probably a common origin with the organs of the lateral line of fish. In the lower forms the ductus endolympha ticus retains its communication with the exterior on the dorsum of the head, and in some elasmobranchs the opening is wide enough to allow the passage of particles of sand into the saccule. In certain teleostean fishes the swim bladder forms a secondary communication with the internal ear by means of special ossicles. Among the Cyclostomata the external semicircular canals are wanting; Petromyzon has the superior and posterior only, while in Myxine these two appear to be fused. In higher types the three canals are constant. Concretions of carbonate of lime are present in the internal ears of almost all vertebrates; when these are very small they are called otoconia, but when, as in most of the teleostean fishes, they form huge concretions, they are spoken of as otoliths. One shark Squatina, has sand instead of otoconia. The utricle, saccule, semicircular canals, ductus endolymphaticus and a short lagena are the only parts of the ear present in fish.

The Amphibia (q. v.) have an important sensory area at the base of the lagena ; it is probably the first rudiment of a true cochlea. The ductus endolymphaticus has lost its communication with the skin, but it is frequently prolonged into the skull and along the spinal canal, from which it protrudes, through the intervertebral foramina, bulging into the coelom. This is the case in the com mon frog. In this class the tympanum and Eustachian tube are first developed ; the membrana tympani lies flush with the skin of the side of the head, and the sound-waves are transmitted from it to the internal ear by a single bony rod—the columella.

In the Reptilia the internal ear passes through a great range of development. In the Chelonia and Ophidia the cochlea is as rudi mentary as in the Amphibia, but in the higher forms (Crocodilia) there is a lengthened and slightly twisted cochlea, at the end of which the lagena forms a minute terminal appendage. At the same time indications of the scalae tympani and vestibuli appear. As in the Amphibia the ductus endolymphaticus sometimes ex tends into the cranial cavity and on into other parts of the body. Snakes have no tympanic membrane. In the birds the cochlea re sembles that of the crocodiles, but the posterior semicircular canal is above the superior where they join. In certain lizards and birds (owls) a small fold of skin represents an external ear. In monotremes the internal ear is reptilian, but above them the mam mals always have a spirally twisted cochlea, the number of turns varying from one and a half in the Cetacea to nearly five in the rodent Coelogenys. The lagena is reduced to a mere vestige. The organ of Corti is peculiar to mammals, and the single columella of the middle ear is replaced by the three ossicles already described in man. In some mammals, especially Carnivora, the middle ear is enlarged to form the tympanic bulla, but the mas toid cells are peculiar to man.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-See

any standard work on Anatomy ; also R. ButBibliography.-See any standard work on Anatomy ; also R. But- ler, Laryngoscope, 191.4; P. Bellocq, Etude anatomique de l'oreille interne osseuse, etc. (1919) ; A. H. Cheatle, Photographs demonstrating the Surgical Anatomy of the Temporal Bone with Catalogue and Guide (1921) ; G. Portmann, J. de Med. de Bordeaux (1921) ; Stenger in Katz and Blumenfeld, Handbuch d. Spec. Chir. d. Ohres. u. d. oberen Luftwege (Leipzig, 1922) (bibl.) ; N. Solvotzoff, Monatschr. f. Ohrenh. (1925) ; H. P. Chatellier, Ann. de Mal. de l'oreille, etc. (1923).(F. C P.)