Animal Ecology

ECOLOGY, ANIMAL. Animal ecology is rather a difficult subject to define, because it lies on the borderlines of so many other subjects, and also because comparatively little work has so far been done on it, so that its exact scope and limits still remain to be established. In a general way animal ecology seeks to give some definite form to the vast number of observations which have been accumulated during the last few hundred years by field naturalists and various other people interested in wild animals. It was Haeckel who first invented the word "oecology" in the year 1869; but, owing to the predominantly morphological and physiological interest which was taken in animals during the latter half of the 19th century, the subject that he so named was largely ignored by zoologists. It was the botanists who developed further the idea of studying scientifically the relations between the plants and their environment, and when American botanists, and later, American zoologists, began to produce a great deal of important work in ecology during the beginning of the aoth century, the "o" was gradually dropped and the word was adopted in its present form, although the older spelling is still widely used on the Continent. "Ecology" corresponds to the older terms "Natural History" and "Bionomics," but its methods are more accurate and precise, and, while much of the earlier work was centred upon the study of adaptations with the idea of proving the theory of natural selection, the modern trend is in a differ ent direction. Ecology is now concerned more with an attempt to reduce and co-ordinate into some scientific scheme the existing information (which is enormous, but appallingly scattered) on the habits, life histories, and numbers of all the different animals, with a view to solving some of the urgent practical problems which are cropping up everywhere as a result of man's becoming civilized and interfering with the animal and plant life around him. Pro fessor J. A. Thomson has rather aptly called animal ecology "the New Natural History," and has pointed out that, although it can never reach in its methods "the icy perfection of comparative anatomy" yet it has nevertheless an important gap to fill in bio logical work. To say that animal ecology deals with "the relations of animals to their environment" is to give a formal definition that conveys no idea whatever of the manifold and exciting prob lems with which the ecologist has to deal. Instead, therefore, of endeavouring to force the subject into a strait-waistcoat, it will be more to the point to begin by describing a few examples, selected more or less at random, of the type of problem which may confront the animal ecologist working in the field. We can then proceed to inquire what stock of information we possess at the present time ; the uses which can be made of it ; and then we may be in a position to suggest the most desirable methods of classifying this information, and the lines along which research upon the ecology of animals may best be directed in the immedi ate future.

During the winter of 1910–r, r, a deadly epidemic of pneumonic plague broke out in Northern China, and killed off about 6o,000 Chinamen. This outbreak originated from a previous epidemic amongst the tarbagans or wild marmots (Arctomys bobac) which inhabit the semi-desert steppes of Mongolia, and are the most dangerous reservoir of plague in that region. We now know, through the researches of Wu Lien-Teh and others, that this marmot only suffers from really severe outbreaks of plague at comparatively long intervals (about every ten years), at times when the numbers of the animals have for some reason become too great, and the population in consequence too dense. This overcrowding favours the spread of the plague bacillus, and pro duces suitable conditions for epidemics in the marmots ; when these occur, any accidental contact, causing infection to spread to a man, enables the bacilli to spread through the Chinese popu lation, which in its turn is usually overcrowded. From this point, the epidemic spreads from one person to another by the breath ing of infected air, after the manner of influenza. A climatic factor comes in here, for it is only in countries with a moist cool climate that widespread epidemics of pneumonic plague occur; in hotter and drier regions the bacilli of plague cannot be success fully carried about in the droplets of moisture breathed out by infected people. In these hotter countries, e.g., India and South Africa, plague occurs in the bubonic form, and is transmitted by the bites of fleas, which in turn have become infected with bacilli from rats or other rodents.

The complete cycle of events in China is not, however, entirely to be explained by the marmots, for it is an interesting fact that before about 1890 severe epidemics of plague in man were much less frequent in that region. The increase in modern times has probably been due to two other factors: the arrival of a great many Russian immigrants from the west, partly as a result of the establishment of the Trans-Siberian railway, which runs for part of its way straight through the marmot country; and also the penetration of Mongolia in recent years by an increasing number of Chinese colonists from the south-east. These new arrivals, being ignorant of the deadly nature of sick marmots, appear often to have handled them carelessly or eaten them, and so contracted plague, in some cases starting huge epidemics in the human population, like the one mentioned above, or like that which took place in 1921 and killed about 9,00o Chinamen.

The example just given illustrates the varied nature of the knowledge required for the complete solution of problems in animal ecology. Here the problem touches on zoology, medicine, bacteriology, climatology, history, human population problems, ethnology—to mention only the most obvious subjects involved.

The example of plague in Chinamen also illustrates the fact that man's relation to his environment (especially to his animal environment) may become suddenly strikingly altered when he migrates to a new part of the world. Most primitive peoples have settled down into a more or less harmonious relationship with the animals and plants of their own country. The Red Indians of North America, or the natives of Siberia, usually took care not to kill too many of the animals upon which they depended for food, so that the stock would not become exhausted—any failure to follow this principle would result in starvation and extinction of the tribe; and according to Percival the Masai of Central Africa have long been aware that malaria is carried by mosquitoes —in fact, their word for catching malaria means literally "I have been bitten by a mosquito." In England we have been here long enough to have settled down into a fairly comfortable balance with the animal community of which we are privileged members; but in the newer colonies, we see the effect of man's interference with the balance of nature demonstrated in very remarkable ways.

The Hawaiian islands afford a number of very interesting cases of this sort. The sugar-cane leaf-hopper (Perkinsiella sacchari cida) was introduced by accident towards the end of the i9th century, and, having no natural enemies, it flourished greatly. It was first noticed as a pest about 1887, and by 1902 it had increased to an enormous extent, so that on one plantation the sugar produc tion fell in three years from 19,00o tons to 7,000. Perkins and other workers studied the insect in its native haunts in Australia, and after trying several different natural enemies, succeeded in almost completely controlling the leaf-hopper by introducing into Hawaii a Chalcid wasp (Paranagrus optabilis) from Queensland, with an allied species from Fiji, both of which parasitize it. Eighteen months later the leaf-hopper damage fell to about half its former proportions, and next year about three-quarters of the plantations were under control. Later on, a Capsid bug (Cyrr torrhinus mundulus), which sucks the eggs of the leaf-hopper, was also successfully introduced from Queensland. There are now comparatively few sugar-cane leaf-hoppers left in Hawaii, although in some years revivals in numbers tend to occur, and these have to be checked again.

A third example of an ecological problem is that of the Type or willow grouse (Lagopus lagopus) in Norway. Of late years this bird has become increasingly scarce in Norway, and since it is an important game bird a number of people have investi gated its ecology with a view to finding out why it has become so much reduced in numbers. It appears that in earlier times (until about 19oo) the willow grouse used to be subject to very marked and at the same time very regular fluctuations in numbers, and that one of the factors producing this was a coccidian proto zoan (Eimeria avium) which gave rise to epidemics among the willow grouse whenever the latter became overcrowded. Some other factors appear to have been at work in controlling the actual years of abundance also, since the willow grouse cycle coincided very closely with the similar three or four year cycle in lemmings and mice in Norway, which also have periodic epi demics, but of an entirely different nature. It appears that in recent years the epidemics in grouse have become much more fre quent and severe, so that the population is kept permanently at a very low ebb, and increase up to the abundance of former "crown years" is no longer possible. The explanation of this state of affairs which has been put forward by Brinkmann is this : normal ly the number of sick individuals in the coveys of willow grouse is kept down by birds of prey, for the heavy infestation by the parasite has the effect of reducing the flying power of birds, so that the sick are more easy to catch than the healthy. In this way the proportion of heavily infected birds, even in epidemic periods was always kept below a certain level ; but in recent years birds of prey have been persecuted and greatly reduced in numbers, owing to the damage they do to poultry, etc., on farms. In consequence it seems that the ground occupied by the willow grouse has become very heavily infected with the spores of Eimeria, and the density of the parasites has increased to such a point that the grouse have epidemics nearly every year, instead of every four years. Besides being interesting in other ways, this example illustrates how the obvious idea of enemies being hostile to their prey fails to hold good when we are dealing with the regu lation of numbers. Here the hawks were by their actions increas ing the density of the willow grouse, instead of merely tending to reduce it.

It would be possible to give an indefinite number of similar examples all tending to show the immense importance to mankind of a knowledge of the means by which the numbers of animals are controlled, or of the factors in the environment which affect the life histories and distribution of the various species. It is not surprising to find that man's inter-relations with other animals bulk very large in the picture, since man himself is only one ani mal in a huge community of other ones, and is still subject to many of the same influences as the wild species. Malaria and mosquitoes; sleeping sickness and tsetse flies; earthworms in the soil ; the control of nitrogen bacteria by protozoa in the soil ; the enemies of crops, of timber and of other resources ; the conser vation of the supply of game, or of marine fisheries; the ravages of hookworms among tropical peoples; rats as reservoirs of dis eases such as plague and jaundice, or as the destroyers of pro duce; the control of insect pests by birds; the effects of climate upon man himself—all these are ecological problems, requiring for their solution a background of ecological principles, and an ordered and skilfully organized knowledge of animal ecology. Human civilization is faced in many parts of the world with grave economic and medical problems, which can only be solved success fully along ecological lines, and it seems quite possible that unless they are solved in time, the civilization will be in danger of sink ing gradually and collapsing under the strain, or at any rate of be coming too unpleasant to be worth retaining. At the very least, animal ecology has an important and very urgent contribution to make towards the world's happiness. This is probably not widely realized : five years ago an eminent zoologist remarked that ecology was only playing with science, while an equally famous entomologist was heard to say that ecologists were an obscure sect of the followers of Lamarck.

Having to some extent made clear the scope of animal ecology, we may now proceed to take stock of our general knowledge. What information is there about wild animals? Animal ecology is in rather a peculiar position, for there is an enormous amount of information in existence about the habits, distribution and num bers of wild animals, but much of it is either recorded in an unsuitable way and is therefore useless, or else only to be found in an extremely scattered form. A great many of the facts about animal life are never published at all, either because the observers have not the opportunity or training to describe them, or because they do not realize the value or significance of the data. The subject thus resembles a large nebula floating round in space : it will be some time before all the separate particles become con densed into a solid body. Another peculiarity of animal ecology is that many of the most interesting observations are made by people who are not scientifically trained at all—gamekeepers, fishermen, lighthouse keepers, clergymen, country gentlemen, amateur naturalists (but most of these are collectors only) or travellers; or if they are scientists, they are often not actually zoologists, but probably doctors, experts in forestry or agriculture, or travellers with an eye for the interesting and unusual. As a result, there exists, as we have said, a very large, but peculiarly diffuse body of facts about the life and manners of wild animals. There is hardly any journal which is not capable of being of some use to the ecologist. Periodicals on meteorology contain elabo rate analyses of the behaviour of animals during thunderstorms, or the times of arrival of migrant birds in spring ; the daily press often records "plagues" of animals like ants and mice, which pass unnoticed by more sober journals ; engineering magazines may record examples of pests which attack marine timber works, or describe the animals found in water supplies, or cases of cater pillars holding up railway trains. The key fact for which the ecologist is looking may be firmly embedded in the middle of a work of travel mainly devoted to railway systems, or the songs of the Copper Eskimos, or the religion of the Bhotias. The imme diate tendency (at any rate the immediate need) in ecology is for the co-ordination of these scattered facts, for the digestion of these gigantic boluses of unassimilated first-hand observations; and lastly, and most urgently of all, we require ideas, to link up all these stray facts into an effective whole. The proportion of facts to ideas in animal ecology is at present indigestibly high ; the journals of ornithology and entomology are swollen fat and heavy with such valuable, but unassimilated matter.

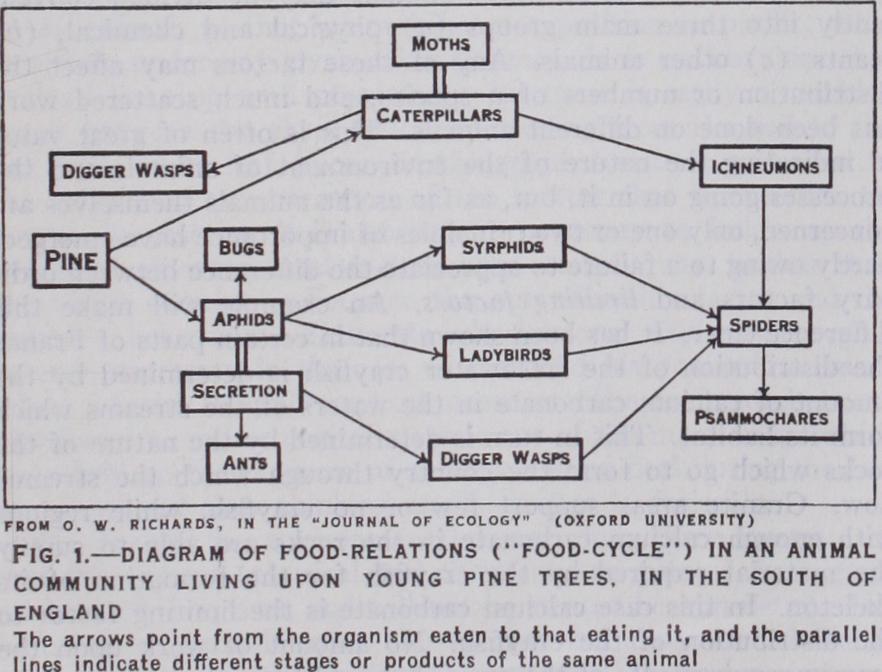

What, then, are the lines along which this organization should proceed? In the following pages an attempt will be made to indi cate the most promising of these lines, and at the same time to describe the more important principles which have already been established. The general thread running through this account is as follows. Animal ecologists doing pure research have carried out a number of ecological surveys, established the habitats of a number of animals, and gained some insight into the nature and workings of their environment, together with some idea of the ways in which environmental factors affect a few species. At the other end of the subject, there are hundreds of economic entomologists and other zoologists, who are studying problems concerned with the number of animals, and who are in need of a basis of principles upon which to work. The gap between these two groups of ecologists will have to be bridged by professional ecologists studying the organization of animal communities. For it is found that by analyzing the lists of animals from different habitats and arranging the species according to their food-habits, it is possible to obtain just the kind of data required for the solu tion of the more practical problems connected with animal num bers and their control. One of the tasks of ecologists at the pres ent time is to provide a system of basic principles which can be used by other people such as medical investigators, or evolution ists, or botanists, or economic zoologists working in the field.

The first step in the study and consideration of the animal ecology of any region is the carrying out of a primary ecological survey; this involves (a) the collection and listing of all the species of animals found in the district and (b) the description, in as accurate a way as possible, of the exact habitats of all the animals which have been collected. The first part of this task is more easy than the second. For many countries we now have a fairly clear idea of the species which occur there, and of the gen eral distribution of each. In some countries (England among them) this sort of work has rather tended to run to seed, and has often degenerated into the accumulation of lists which refer to districts which may have quite arbitrary limits, bearing no rela tion whatever to the ecological habitats of the various animals. For instance, natural history societies frequently spend consider able energy in making lists of animals for counties, or for the country within a certain radius of some town. Such lists are almost, if not altogether, useless. They show how a means can easily be confused with an end. The second point is the impor tance of collecting, with all specimens, ecological notes about the habitats of the animals. In order to do this properly, it is of course necessary to have good topographical and geological maps, together with maps of, or at any rate organized information about, the plant associations, and also if possible meteorological and climatological data for the district. With such information at hand, it is possible to define in a rough, but useful, preliminary way the general habitats and distribution of the different species of animals. Fortunately the necessity of recording the exact habitats of animals is becoming widely recognized, even among collectors of insects. Organized ecological surveys have been started in many places during recent years. The fine work of the American Bureau of Biological Survey, both in the U.S.A. and in Canada; Wesenberg-Lund's comprehensive studies of the fresh water animals of Denmark; the work of Annandale in India, and of Johansen in Arctic Canada and Greenland ; these are examples of the movement for obtaining an organized knowledge of the ecological distribution of animals. In England, very few such surveys have as yet been carried out with anything approaching completeness, but we may mention the survey by Richards of animal communities living in various habitats on Oxshott com mon; that of freshwater Crustacea in the English lakes by Gurney; of freshwater animals in Welsh streams by Carpenter; and certain valuable work on marine plankton communities in the North sea, by Hardy and others. But the general ecological distribution of English animals has at present often to be left to the imagination, or to be deduced from analogy with what is known from the Continent. This applies more particularly to our knowledge of the animal environment (food, enemies, parasites, etc.) of species. The numerous local natural history societies (over 5o in number) which exist all over the British Isles, form a skeleton organiza tion for this sort of enterprise, which, like the tides, has still to be harnessed and directed along the most useful lines. For details of carrying out surveys, and collecting animals, the reader is referred to the relevant sources at the end of this article.

When the preliminary stage of making lists has been reached and completed certain facts about the distribution of animals in nature begin to emerge. The first is that the habitats of animals —those various combinations of environmental factors which affect them and control their occurrence and numbers—can be classified and arranged in a large number of ways. Secondly, each different habitat possesses its own characteristic community of animals. The number of different habitats in which animals can be found living is at first sight bewilderingly great. Almost wherever one looks animals can be found in greater or less vari ety; on the bottom of the sea at a depth of several miles; in the throats of turkeys ; in the baleen plates of a whale ; in hot springs; on the snow of high mountains ; living and feeding on the algae which, in turn live among the hairs of the sloth; on the bottoms of ships; in stores of food (there is a moth whose larva lives on tobacco and strychnine) ; on the surface film of water; in the pools of acid water found in tree-holes ; in lichens on the sur face of windswept rocks ; not to speak of the vast number of more obvious habitats afforded by vegetation, soil, and water. How are we to classify these different habitats in a convenient way, so as to avoid the reproach usually levelled at ecologists, that the sub ject is nothing but a chaotic mass of unrelated facts? It is obvi ously imperative to have some scheme in order to provide a com mon system to which all the detailed records of animals by habitats can be referred, and in order to understand their distribu tion in nature. There are three useful ideas which help to reduce the chaos to order : Gradients in the Environment.—There are a number of clearly marked gradients in important or controlling environ mental factors which enable us to arrange some of the habitats, and therefore their animal communities, in definite series. A good example of this is the gradient in temperature and light which runs from the poles to the equator. Along this gradient the con ditions change gradually through arctic, subarctic, and other zones to tropical conditions, and at the same time produce corre sponding changes in the animal and plant communities. A fact which immediately emerges is the enormous influence that vegeta tion has upon the nature of the animals' habitats. Climatic fac tors do, of course, act directly on animals, but a great deal of their influence is felt indirectly through plants, which frequently change the whole character of the climate, as far as the animals are concerned. For instance, the light intensity inside a pine wood may be only about half that outside, with the result that animals living among pine needles occupy, in the daytime, con ditions similar to those at dusk outside in the open. Another effect of plants is to create a much wider variety of "climatic" conditions (e.g., humidity) than would otherwise exist, so that a more varied choice of habitats is open to animals, with conse quent multiplication of the number of species. Again, plant asso ciations are usually rather sharply marked off from one another, owing to the way in which dominant plants compete for light and food, so that the animal communities within them tend also to be rather more sharply separated from one another than they would otherwise be. This separation is well shown in the zones found up the sides of mountains, where we find altitude corre sponding to latitude--a phenomenon seen at its best in the Himalaya, where a traveller can sometimes listen to English and tropical birds calling at the same time in their different zones. These have been termed "life zones" by American ecologists, and the animal communities living in them have been more fully studied in North America than anywhere else, partly owing to the grand scale upon which they can be seen on the° sides of the Rocky Mountains. In this connection the work of Grinnell and Storer on the life zones of the Yosemite region in the Sierra Nevada should be consulted, as one of the best examples of the way in which preliminary surveys can be carried out. The method of zoning animal communities with reference to some master factor in the environment is a useful one, and many such gradi ents can be found in nature. For instance, there is the vertical gradient in light and oxygen in the sea, or in freshwater lakes; the vertical gradient in salt content of water as we pass from alpine lakes down to the sea; gradients in water content of the soil, which are responsible for well-defined zones dominated by different species of plants; many more examples of this nature could be quoted.

Ecological Succession.

The second important idea which can be profitably used in arranging animal communities, is an ex tension of the one just described. This is the idea of ecological succession or orderly changes of the habitats from one into another. Important changes, usually rather slow ones, are con tinually taking place in the environment—rivers change their course, with corresponding destruction of existing land and forma tion of new; the climate changes from a temperate one to an arctic one, with the advance of an ice-sheet ; the land rises or falls; valley lakes become silted up, or filled with vegetation and formed into marsh, and finally dry land. Such changes are happening everywhere, so that any one habitat seldom stays as it is for any length of time ; but the most important kind of eco logical succession is that caused by the "development" of vegeta tion. Ecological succession or development of plant communities occurs usually in a definite orderly, and predictable way, the changes being brought about mainly by the growth and decay of the plants themselves. These, by depositing humus, change the character of the soil, and are driven out and replaced by other species. There are other processes at work also (see PLANTS : Ecology and Distribution). The work of botanists has enabled plant communities to be arranged in series which represent their relationships both in space and time; and, in so far as animals also depend on the plants, these systems are of great importance to the animal ecologist and form a convenient means of classifying communities. The works of Tansley and Clements should be consulted in this connection. A number of papers and a few books on the classification of animal communities have been published ; of the latter the most useful are Shelf ord's Ani mal Communities of Temperate America, and Haviland's Forest, Steppe and Tundra.