Artistic Anatomy

ARTISTIC ANATOMY The representation of the anatomical form of man as applied to the Graphic Arts may be called Artistic Anatomy. This form of illustration may be divided into three groups : (I) The sche matic, (2) That which represents the subject exactly, (3) The ideal conception or the ideal figure, constructed from the mean proportion of several types.

The schematic drawing is one which represents in outline the main characteristics of the object. It may be drawn with little or no regard as to the exact knowledge of the form. It has been of use in setting forth certain physiologic principles by the general form and location of the organs of the body, and especially used in post-mortem and zootomic comparisons.

The true drawings occur particularly in pathologic anatomy, where various and unknown forms are sought and where certain organs have to be shown in the individual, as in the case of human embryology and comparative anatomy.

The representation of the ideal is the only form suitable for teaching—and the very development of this figuration corresponds with the growth of the science of anatomy in all its periods. This type of drawing presupposes a vast amount of previous study of the human figure. It cannot come out of a period in which the artistic development overshadows that of the science of anatomy. This vague feeling for beauty, with a corresponding neglect of the real, was evidenced in an early period of anatomical illustra tion, when conditions favoured an artistic point of view, as was the case in the first half of the i6th century. This, however, changed as the cold scientific and extensive dissection was prac tised during the 17th and i8th centuries. It is only the combina tion of these two tendencies which can satisfactorily serve the advanced science of anatomy and the modern art of drawing, bringing to perfection through exactness of detail and ceaseless observation a comprehension of beauty in the entire figure.

In artistic anatomy, nothing else is of value to the artist but the idealized drawing. The more he eliminates unessential, the better; the keener his eye for the unnecessary, the bigger his vision of the true needs of the artist. The unnecessary is harm ful, and the artist's presentation of too much anatomy makes of him a professional anatomist. Of immediate necessity is the study of the antique, or the older plaster models of Greek figures, for in drawing the nude the young artist visualizes the actual healthy form in all its fulness of life and movement, thus adding an ele ment which can never be supplied by purely anatomic delineation.

The development of artistic anatomy was not of outstanding consequence before the i 6th century. Only a few anatomical en gravings and woodcuts are found to that date. Even the draw ings that Aristotle used in supplementing his works on anatomy have been lost. Figurations of skeletons and representations of bodies on cameos, seals and bronzes were common, but these delineations never served the purpose of anatomic instruction; they were rather of an emblematic nature : symbols of death, magic amulets, references to the fable of Prometheus, etc. In view of this, artistic anatomy may be divided into the following periods : To the 16th Century.—Anatomical drawings of the Classic Period and the Middle Ages were known, and even mentioned by Aristotle, but so few have come to us for study that the subject cannot be adequately covered. Before the time of Berengario, commonly called Berenger of Carpi, about 1521, most of the attempts were schematic drawings for medical observation, artis tic anatomy remaining in the background as a private study and depending largely upon professional anatomists for its develop ment.

The 16th Century.

Although the name Berengario belongs only to the annals of medicine and will be remembered as the most zealous and eminent in cultivating the anatomy of the human body, it was his day, and that of Vesalius (1514-64), that marked the beginning of the attempt to free the anatomical draw ing from schematic and arbitrary features and recognized its place in art. This artistic anatomy, was promoted by both artist and anatomist for the sole purpose of instruction. It was during this period that the Italian School of Anatomy reached its height of interest in the woodcut; it was during this period that sculpture and painting adopted proportions of the human body never be fore developed ; it was during this period that Michelangelo lived. Other 16th century artists who contributed to the study of anatomical figures were Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian and Diirer.The 17th Century.—A comparative study of the antique, a clinging to Vesalian patterns, and the advent of independent pub lications on artistic anatomy mark the development of the study in the 17th century. A closer training in details and an effort toward the artistically perfect reproduction may also be included.

18th-19th Century.—Albinus (1697-177o) was one of the most famous teachers of anatomy in Europe, his classroom at the Leyden School of Anatomy being frequented not only by stu dents but by many practising physicians. The Leyden school exerted untold influence in creating a greater exactness in all de tails. The styles of both Vesalius and Albinus were used as pat terns in anatomical drawing, many independent attempts proving unsuccessful.

About 1778 combinations of utmost anatomic truths with artis tically beautiful reproductions were brought out. The adoption of the steel engraving, lithography, the daguerreotype, as well as the revival of the woodcut in an improved form, meant an advance in the art; the exclusive use of the Albinian patterns gave rise to a greater independence. In fact, 1778 may be given as the beginning of the period in which the most valuable material on artistic anatomy was produced. Modern scientific medicine had gained its stride and was already moving swiftly toward the goal of a well-organized body of real knowledge capable of continuous growth. And this development may be shown in the bibliographic list as given below, the chain running from the first half of the 18th century to the present day. This bibliographic account gives the distinctive examples of anatomic illustration, including the modern work in both the technical and the artistic.

For the young student of anatomy as applied to art the simple drawing is the most . effective in learning to construct the human figure. The eye must follow a line or a plane or a mass, which in construction becomes a moving line, a moving plane, a moving mass. But the mental construction must precede the physical, and in this the concept of mass must come first, that of the plane second, that of line last.

Certain laws enter into the functioning of the various organs of the body, just as pronounced as they are in controlling any other machinery. To the bones, for example, which make up the pressure system, belong the laws of architecture. as in the dome of the head, the arches of the foot, the pillars of the legs, etc.; also the laws of mechanics, such as the hinges of the elbows, the levers of the limbs, etc. Ligaments constitute the retaining or tension system, and express other laws of mechanics. Muscles produce action by their contraction or shortening and are ex pressed in the laws of dynamics and power, as well as the laws of leverage.

In giving herewith only an outline of the construction of the main parts of the body, the author presupposes a rudimentary knowledge of drawing, on the part of the student, and offers the following, in connection with the illustrations only as a further guide in studying the elements of anatomy and becoming more adept in the art of drawing.

The Hand.—In drawing the hand the artist must realize that, as in the human figure, there is an action and inaction side. When the thumb side is the action side the little finger is the inaction side. The inaction construction line runs straight down the arm to the base of the little finger. The action construction line runs down the arm to the base of the thumb at the wrist, from there out to the middle of the joint, at the widest part of the hand; thence to the knuckle of the first finger, then to that of the second finger, and then joins the inaction line at the little finger. How ever, with the hand still prone, when it is drawn from the body the thumb side becomes the inaction side and is straight with the arm, while the little finger, corresponding previously to the thumb, is at almost right angles with it. The inaction construction line now runs straight to the middle joint of the thumb, while the action line runs to the wrist on the little finger side, thence to the first joint.

The Fingers.—Each of the four fingers has three bones. The middle finger is the longest and largest, because in the clasped hand it is opposite the thumb and with it bears the chief burden. The little finger is the smallest and shortest and most freely mov able for the opposite reason. The middle joint of each finger is the largest, and, like all the bones of the body, the bones of the finger are narrower in the shaft than at the ends. In the clenched fist it is the end of the bone of the hand that is exposed to make the knuckle. Each of the three joints moves about one right angle except the last, which moves slightly less. The movements of the joints are also limited to one plane, except the lower one, which has also a slight lateral movement, as shown when the fingers are spread.

The Thumb.—The centre of all the activities of the fingers, the hand, and the forearm, is the thumb. The fingers, gathered together, form a corona around its tip. Spread out, they radiate from a common centre at its base ; and a line connecting their tips forms a curve whose centre is the same point. This is true of the rows of joints also. The thumb has three joints, and its bones are heavier and its joints more rugged than those of the fingers. It is pyramidal at the base, narrow in the middle, pear shaped at the end. The ball faces to the front more than sideways. The thumb reaches to the middle joint of the first finger. The last segment bends sharply back, its joint having about one right angle of movement, and only in one plane. The middle segment is square with rounded edges, smaller than the other two, with a small pad. Its joint is also limited to one plane. The basal seg ment is rounded and bulged on all sides. The joint of its base is a saddle joint, with the free and easy movement of one in a saddle.

The Arm.

The forearm has two bones, lying side by side. One, the radius, is large at the wrist and the other, the ulna, is large at the elbow. Diagonally opposite the thumb, on the ulna, is a bump of bone which is the pivot for both the radius and also the thumb. Muscles must lie above the joint they move, so the muscles that bulge the forearm are mainly the flexors and ex tensors of the wrist and hand. The flexors and pronators form the inner mass at the elbow, the extensors and supinators form the outer mass.Both the above masses arise from the condyles of the humerus, which is the bone of the upper arm. The part of the humerus near the shoulder is rounded and enlarged, where it joins the shoulder blade. The lower end is flattened out sideways to give attachment to the ulna and radius, forming the condyles. The shaft itself is straight and nearly round, and is entirely covered with muscles except at the condyles.

The Shoulder.

The deltoid muscle, triangular in shape, gives form to the shoulder. Just below the base is a ripple which marks the head of the arm bone. The masses of the shoulder, arm, fore arm and hand do not join directly end to end with each other, but overlap and lie at various angles. They are joined by wedges and wedging movements. Constructing these masses first as blocks, we will have the mass of the shoulder, or deltoid muscle, with its long diameter sloping down and out, leveled off at the end ; its broad side facing up and out; its narrow edge straight forward. The mass of the forearm overlaps the end of the arm on the out side by a wedge that rises a third of the way up the arm, reaches a broad apex at the broadest part of the forearm and tapers to the wrist, pointing always to the thumb; and on the inside by a wedge that rises back of the arm and points to the little finger. In the lower half of the forearm, the thin edge of the mass, toward the thumb, is made by a continuation of this wedge from the outside. In the back view of the arm, the mass of the shoulder sits across its top as in the front view.

The Neck.

Curving slightly forward, the neck rises from the sloping platform of the shoulders. The strength of the neck is at the back of the head, this portion being somewhat flat and over hung by the base of the skull. The sternomastoid muscles descend from the bony prominences back of the ears to meet almost at the root of the neck, forming a triangle whose base is the canopy of the chin. In this triangle below is the thyroid gland, larger in women, and above it the angular cartilage of the larynx, or Adam's apple, larger in men.

The Head.

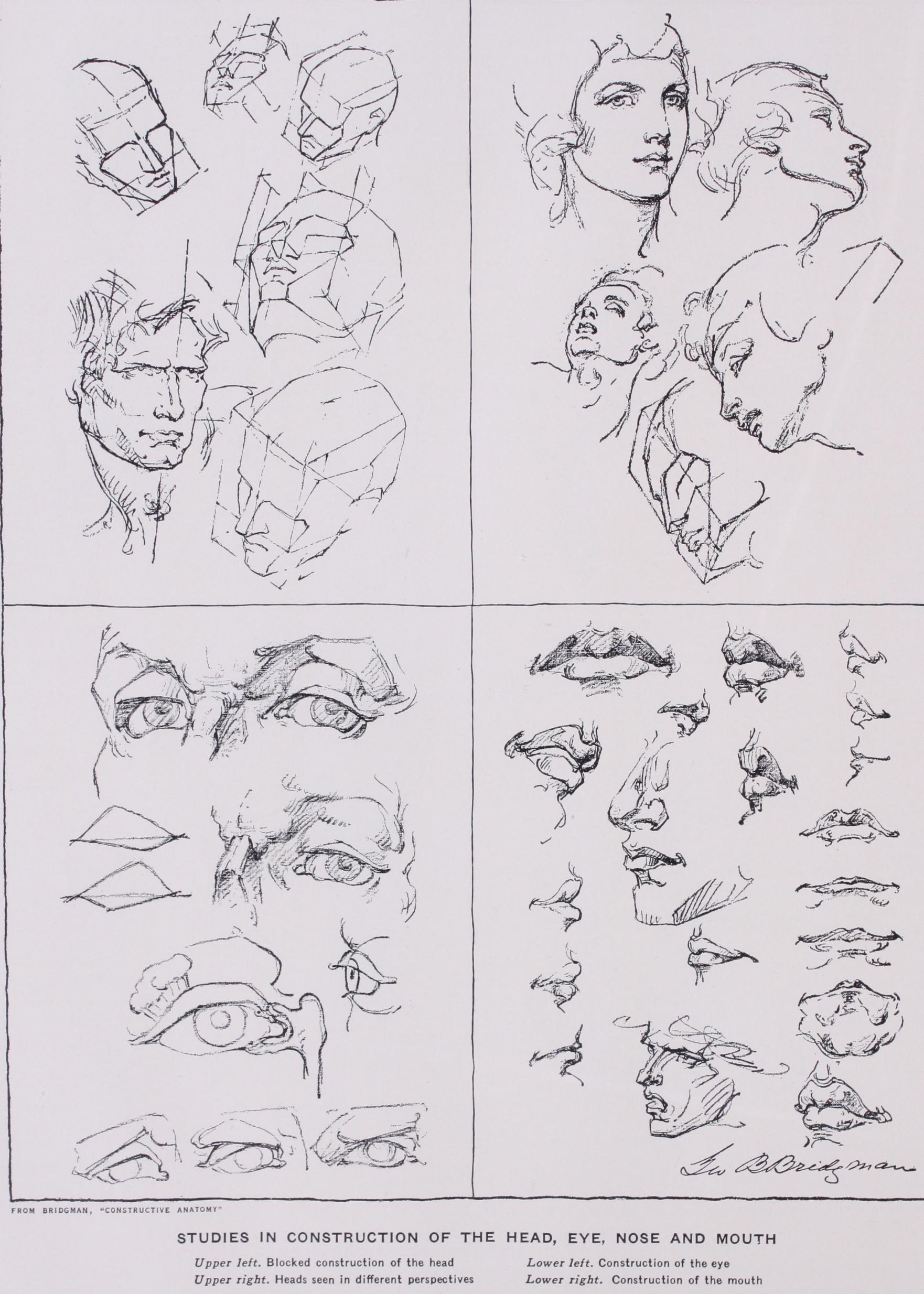

Both the oval and the cube have been used by artists as a basis for drawing the head, but the cube seems pref erable in that the oval is too indefinite and offers no points for comparison, no basis for measurement, and the eye does not fix on any point in a curved line. The block not only carries the sense of mass, but provides a ground plan on which any form may be built, as well as its perspective and foreshortening. The element of bilateral symmetry enters the drawing of the head. A vertical line in the centre divides the head or the trunk into parts equal, opposite and complemental. The right eye is the counterpart of the left; the two halves of the nose are symmetrical; the limbs, except for changes of position, are nearly exact though reversed duplicates of each other.The cranium, the skeleton of the face, and the jaw constitute the masses of the head. Into the rounded mass of the cranium sets the narrower mass of the forehead bounded by the temples at the sides and by the brows below. From the lower outer corners of the forehead the wedge of the cheek bones begins, moves outward and downward until it just passes the curve of the cra nium, then down and in, in a long sweep, to the corner of the chin. The two cheek bones together form the central mass of the face, in the middle of which rises the nose.

The planes of the head are those of the forehead, sloping upward and backward to become the cranium. The sides turn sharply to the plane of the temples. The plane of the face, divided by the nose, is broken on each side by a line from the outer corner of the cheek bone to the centre of the upper lip, making two smaller planes. The outer of these tends to become the plane of the jaw, which is again divided, etc. The relations of these masses and planes is to the moulding of a head what architecture is to a house. They vary in proportion with each individual and now must be carefully compared with a mental standard.

The Eye.

Below the eyebrow, on the lid, are three planes, wedging into each other at different angles. The first is from the bridge of the nose to the eye. The second is from the brow to the cheek bone, which is again divided into two smaller planes, one sloping toward the root of the nose, the other directed toward and joining with the cheek bone. The lower lid is stable; it is the upper lid that moves. It may be wrinkled and slightly lifted in ward, bulging below the inner end of the lid. The cornea is al ways curtained by the upper lid, in part. The immovable masses of the forehead, nose and cheek bones form a strong setting for the most variant and expressive of the features.

The Nose.

The bony part of the nose is a very clear wedge, its ridge only half the length of the nose. The cartilaginous portion is quite flexible, the wings being raised in laughter, dilated in heavy breathing, narrowed in distaste, and wings and tips are raised in scorn, wrinkling the skin over the nose.The ears, the mouth, the lips, and the chin, all offer variations in construction, and it is through comparison with others that the art of drawing them can best be acquired.

The Trunk.

The upper part of the body is built around a bony cage called the thorax, conical in shape, and flattened in front. The walls of this cage are the ribs, twelve on each side, fastening to the spine behind and to the sternum or breast bone in front. The first seven are called true ribs, the next three false, and the last two floating ribs. The masses of the torso are the chest, the abdomen or pelvis, and between them the epigastrum, the first two comparatively stable, the middle one quite movable. The shoulders are also movable, changing the lines of the first mass and bulging the pectoral muscles, but the mass itself changes little except the slight change in respiration. The mass of the abdomen is even more unchanging.

The Torso.

In profile the torso presents three masses : the chest, the waist and the abdomen. The mass of the chest is bounded above by the line of the collar bones; below, by a line following the cartilages of the ribs. This mass is widened by the expansion of the chest in breathing, and the shoulder moves freely over it, carrying the shoulder blade, collar bone and muscles. The back view of the torso presents numerous depressions and promi nences, due to its bony structure and the crossing and recrossing of a number of thin layers of muscles. The outside layers manifest themselves only when in action, and for this reason the spine, the shoulder-blade, and the hip-bone are the landmarks of this region.

The Lower Limbs.

The thigh, the leg, and the foot constitute the lower limb. The thigh bone is the longest and strongest bone of the body, and the mass of the thigh is inclined inward from hip to knee, and is slightly beveled toward the knee from front, back and outside. Below the knee is the shin bone, the ridge of which descends straight down the front of the leg, a sharp edge toward the outside, a flat surface toward the inside, which at the ankle bends in to become the inner ankle bone. The outer bone of the foreleg soon overlaid by a gracefully bulging muscular mass, emerges again to become the outer ankle bone. Two large muscles form the mass on the back of the leg.

The Foot.

In action, the foot comes almost into straight line with the leg, but when settling upon the ground it bends to keep flat with the ground. A series of arches form the symmetry of the foot, the function of these arches being that of weight-bearing. The five arches of the foot converge on the heel, the toes being flying buttresses to them. The balls of the foot form a transverse arch. The inner arches of the foot are successively higher, form ing half of a transverse arch whose completion is in the opposite foot. (See COMPARATIVE ANATOMY; ILLUSTRATION ; SCULPTURE.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Francesco Bertinatti, Elementi di anatomia fisiBibliography.-Francesco Bertinatti, Elementi di anatomia fisi- ologica applicati alle belle anti figurative, Torino: P. Marietti, 1837, i. v. 8. Atlas fol. 43 pl.Richard Lewis Bean, Anatomy of the Use of Artists, London: H. Renshaw, 1841, 8. 47 pp., io pl.

William Wetmore Storey (1819-95), The Proportion of the Human Figure, According to a Cannon, for Practical Use. London: Chapman & Hall, 1866, roy. 8. 3 p. I., 63 pp., 7 tab.

Robert Fletcher, Human Proportion in Art and Anthropometry. Cambridge: M. King, 37 pp., 4 pl. 8.

William Rimmer, Art Anatomy. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench and Co., 1884. fol. 2 p. 1., 81 pl.

Julius Constantin Ernst Kollmann (1834-1918), Plastische Anatomie des menschlichen Korpers, fur Kiintstler and Freunde der Kunst. Leipzig: Veit and Comp., 1886, roy. 8. By the professor of Anatomy at Basel. Illustrated with lithographs from hand-drawings, photo graphs from the nude, ethnic studies of facial features arranged on echelon, etc. The text, like Hyrtl's, is of unusual historic interest, and includes special chapters on the anatomy of the infant, human proportions, and ethnic morphology. Among the models used are Sandow, Rubenstein and other celebrities.

Edouard Cuyer, Anatomie Artistique du Corps Humain. Planches par le Dr. Fau, Paris: J. B. Balliere et Fils, 1886, vii.-208 pp., 17 pl. Charles Rocket (1815-190o) . Traite d'Anatomie, d'Anthropologie et d'Ethnographie Appliquees aux Beaux-Arts. Paris: Renouard, 1886. xii.-2 76 pp. Illustrated by pen drawings (in black and white and colours) by G. L. Rochet.

Paul Richer (1849— ) , Anatomie Artistique. Description des formes exterieures du corps humain au repos et dans les principaux mouvements. Paris: E. Plon, Nourrit et Cie., 189o, fol. viii., 1 io pl. Physiologie Artistique de l'Homme en Mouvement. Paris: O. Doin, 1895, 8. 335 pp., 6 pl.

Paul Richer (184.

), Nouvelle Anatomie Artistique du Corps Humain, Paris: Plon. 1906. sm. 4 vi.-177 pp.Ernst Wilhelm Brucke (1819-92), Schonheit and Fehler der mensch lichen Gestalt. Wien: W. Braumuller, 1891, 8. I p. 1., 151 pp. By the professor of physiology at Vienna. A book of unusually attractive and informing character, illustrated with 29 small woodcuts of singular beauty by Herrmann Paar. English translation 1891.

Charles Roth, The Student's Atlas of Artistic Anatomy. Edited with an introduction by C. E. Fitzgerald. London: H. Grevel & Co., 1891, fol. viii —50, 34 pl.

Arthur Thomson. A Handbook on Anatomy for Art Students. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1896. 8. A work of solid merit which has reached its fourth edition. Illustrated with superb photographic plates of the nude, in brown tone, each plate having opposite a schema of the underlying muscles, with legends. The male and female models were chosen not for excessive muscularity, but for all-round symmetry and proportion. Far and away, the best model treatise on the subject in English.

Carl Heinrich Stratz, Die Schonheit des weiblichen Krirpers, Stutt gart, F. Enke, 1898. A treatise on artistic anatomy, based upon direct photography of female models.

Der Korper des Kindes. Fur Eltern, Erzieher, Aertze and Kiinstler. Stuttgart: F. Enke, 1903, 8. xii.-25o pp., 2 pl. An admirable study of surface anatomy of the female body in children, illustrated by photographs from the nude.

James M. Dunlop.

Anatomical Diagrams in the Use of Art Students, arranged with analytical notes, and with introductory preface by John Cleland. London: George Bell & Sons, 1899- rov. 8. 4 p. I., pp. Illustrated with parti-coloured drawings and photographs.George McClelland. Anatomy in Its Relation to Art; an exposition of the bones and muscles of the human body, with especial reference to their influence upon its actions and external forms. Philadelphia: A. M. Slocum Co., 1900, 4. 142 pp., 41 I., 126 pl. Illustrated by 338 original drawings and photographs made by the author. The drawings are mostly rude diagrammatic sketches. The photographs are elegant, well-selected album-pictures of the nude, many of them duplicating the poses and thus demonstrating the excellent anatomy of many antique and modern statues.

Robert J. Colenzo.

Landmarks in Artistic Anatomy. London: Bailliere, Tindall.and Cox, 1902, sm. 4. vi. (i.-1)-56 pp. 6 outlines pl.

Robert Wilson Shufeldt (185.

). Studies of the Human Form, for Artists, Sculptors and Scientists. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Co., 1908, roy. 8. xxxi.-664 pp. Illustrated by photographs of nude models.Sir Alfred D. Fripp and Ralph Thompson. Human Anatomy for Art Students, with drawings by Innes Fripp and an appendix on comparative anatomy by Harry Dixon. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippencott Co., 1911, 12. 296 pp. Contains 151 illustrations, among which are 23 effective photographs from the nude.

John Henry Vanderpool (1857-1911) . The Human Figure. London, 1913, 8.

Edwin George Lutz. Practical Art Anatomy. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918, 8. vii.-2S4 pp. Illustrated with very rudimentary outline drawings by the author.

George B. Bridgman. Constructive Anatomy. Pelham, New York. Bridgman Publishers 1919--213 pp. il. 40o bds.

George B. Bridgman. The Book of One Hundred Hands. Pelham, New York. Bridgman Publishers 1921-172 pp. il. 40o bds.

George B. Bridgman. Bridgman's Life Drawing. Pelham, New York. Bridgman Publishers 1924-172 pp. 2 il. 30o bds. Edward C. Bridgman ; Geo. B. Bridgman (Pelham, N.Y.) .

(E. C. BR. ; G. B. BR.) young artist is primarily interested in mak ing drawings of people, faces and particularly, profiles. A series of charts giving the simple and fundamental rules of proportion is shown as a practical means of starting him in this art.

For the profile, a square is drawn and divided into four equal squares, and the eyes, nose, mouth, chin and ear are placed upon this chart as shown in the progressive illustrations. When the head is complete, the student will discern the egg-shape, which is his first and constant principle, and which should be practised constantly until an egg can be drawn perfectly with one sweep of the hand. Proportions can soon be found on an egg-shape without the aid of a square. Next, the full face is attempted, following the same principles of proportion. It will be observed that the eyes divide the width of the egg-shape into approximately five equal spaces. The two-thirds view and all other variations of the human head should be drawn by means of the egg. With the pro file the beginner will discover that all types of heads, fat, thin and old, may be drawn over the square chart with only minor varia tions in line. The baby and the gorilla are opposite extremes and present exceptions to the rule for placing the eye on the half-way point.

The "Greek Ideal" divided the human figure into eight divisions, each equal to one head.in height; but actually it is seven and one half heads high. The woman's head is smaller, but the divisions of the body similar proportion. Note that in the figure of the man the shoulders are wider than the hips, and the woman's hips are wider than her shoulders.

Taking up these two figures in action, the young artist must learn to look at the figure as a whole; he must consider the one line which expresses the motion he desires, and forget that the figure is made of arms and legs and torso. He must also consider balance. The distribution of weight is directly over the feet, no matter how heavy the load. Without carrying a weight, the chin of the figure is directly over the foot which sustains the weight.

(P. H. ST.)