Draughts

DRAUGHTS. Draughts is a game of skill usually played by two persons on a chequered board of 64 squares. Each player to commence has 12 men of a distinctive colour. In the United States the game is known as checkers.

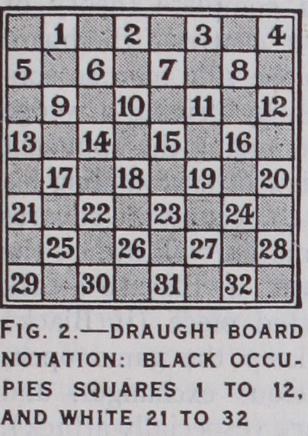

Fig. I shows the board and men set out ready to commence a game. The Black squares are not used throughout the game, and in order to record moves and give a coherent description of play the actual field of operations (i.e., the White system of squares) is numbered as shown in fig. 2. At the set it should be noted that the board is placed with a "double corner" on the right hand of each player, Black's double corner being the squares I and 5 and White's responding double corner 32 and 28. Each player has a "single corner" on his left, Black at 4 and White at 29.

The convention is adopted of assuming that at the commencement of a game the Black men always occupy the first 12 squares (I-12 ), and White the last 12 (21-3 2) . This is merely to get uniformity in recording.

A man moves forward diagonally one step at a time into the next playing square to the right or left provided such square be unoccupied. Thus at the beginning of a game Black has choice of seven different moves—he may play the man on 9 to 13, or the same man to 14, or he may choose 10-14, 11-15, I I-16 or 12-16. Suppose he plays I1-15, then White has choice of seven replies, viz., 21-17, 2 2-1 7, 22-18, 23-18, 23-19, 24-19 and 24-2o A capturing move (shortly "capture" or "take") occurs when a hostile piece is situated in a square contiguous to one belonging to the player whose turn it is to play, with an empty square imme diately behind it. The capture is effected by passing the playing man into the empty square mentioned, removing the man passed over from the board. A cardinal rule is that it is compulsory to take whenever it is possible to do so. When two ways of taking present themselves, the player is free to choose between them. Capturing play is continuous as far as there are opposing pieces en prise, and it is often possible to take two or more in one move, the only condition being that they shall be strung out, each with a vacant square behind it.

When a man reaches the extreme end of the board he is promoted to a "King." Black men crown on reaching any of the squares 29 to 32, and White men similarly on I to 4. A King has the privilege of mov ing and taking backwards as well as for wards, and thus doubles the functions of a man. It is only in rare or exceptional posi tions that a King equals two men in value.

The object of each player is to leave his adversary without a move, and in more than 99% of cases this has to be effected by capturing all his pieces. Briefly, you play to clear him off. The only other way of winning is by so confining what pieces he may have left that he cannot move any of them ; this sometimes happens, and is technically known as a "block," of which more a little later.

If you cannot win you must if possible avoid loss and try to draw. A draw is when neither player can force a win, such as when the opposing forces are reduced to two or three pieces each with no positional advantage to either side. A draw is usually a matter of easy agreement, drawn positions being readily recognized.

As an elementary exercise, to gather up some of the points already explained, play over the following game, No. I:—Black moves first, I I-I 5, White replies 2 2-I 8, offering an exchange which forms the "Single Corner" opening; 15-22 (must take), 25-18 (he has the option of 26-17, but that is a bad move as it would seriously divide the White forces) ; 8-I I, 29-25 (bringing up the single corner man in this way as a support is usually good play) ; 4-8 (the same remark here applies) , 2 5-2 2 (note that 24-19? instead would allow Black a simple three-for-one by I a-1 5, 19-Ib, 6-29); 12-16, 24-20; 10-I5 (by this move Black sets a trap) 27-24? (now this move on the surface looks good, be cause it threatens 24-19 winning a "two for-one," but the first thing a Draughts player should learn is to distrust the ob vious) ; 15-19 ! (Black could dispose of the two-for-one threat by playing 8-12, but that course is unnecessary, as he can make a three-for-three exchange which gains a King and leads to a won game), 24-15 ; 16-19! 23-16 ; 9-14, 18-9 ; 11-25 (the man on 9 is safely pocketed to be taken next move), 32-27 (to the unin itiated White's game does not look entirely hopeless, but trial will show that he is in a very bad way however he may play) ; 5-14 (stronger than taking 6-13), 27-23; 6-Io, 16-12; 8-II, 28-24; 25-29 (crowns; Black has not been in a great hurry to do this, but has first massed the body of his men into a solid position), 24-19 (the exchange by 3o-2 5 ; 29-2 2, affords a little more fight, but with the White forces fatally squandered) ; 14-18 (the first move of a useful four-for-four stroke, the mechanism of which should be remembered), 23-14; IO-17, 21-14; 29-25! 3o-21; I I-16, I ; 7-30 Black wins with great ease, as White can only run his men down the board with an almost unbroken "crown head" facing them and a free King behind them.

The trap which White falls into in the above game when playing 27-24 at the I2th move is of very common occurrence, and is known by the quaint designation of the "Goose Walk." It is easily avoided by moving and so drawing the game.

There are a few points in connection with Draughts which are subject to much misapprehension among those who have little acquaintance with the game or rules. One knotty point is in con nection with the "huff," i.e., a penalty which may be enforced against a player who neglects to capture a piece when he should do so. The "huff" simply consists of the removal by the adversary (before he moves) of the piece which should have effected the capture. Now the offending party has no say whatever as to whether the penalty shall be exacted or not in any particular case. His adversary may require him to put back the illegal move he has just played, and make the proper capture. In such case there is no huff. It would obviously be absurd if a player could evade a well-planned coup by blandly standing the huff.

It is neither good form nor bad form to "man off." The player who objects to exchanges being forced upon him when he himself is in a minority (on the ground that it is "not sport") is simply displaying ignorance. A player is entitled to make, and should make, the best move he can see in any position. Frequently, the only way to press home numerical advantage is to exchange, and so increase the ratio of such advantage.

If a player touch a piece when it is his turn to move, he must play that piece, and if the piece be pushed so as to show over the angle of the square, the move must be completed in that direction.

A man, on reaching the square on the opposing back rank, rests there to be crowned. If he lands there in the course of a capture, he cannot continue capturing as a King.

The ending of two Kings to one is simple. It is a win in all cases for the two Kings, with just one exception which can occur in either single corner.

The ending of three Kings to two, when the weaker party holds one or both the double corners, is apt to be a little puzzling at first. The win is obtained by forcing an exchange, reducing the ending to 2 x I.

In general esteem, Draughts is placed at a disadvantage by the simplicity of its initial presentation. One can play a game with so very little instruction. Critics sometimes point to the large preponderance of drawn games (between experts) over those that are won, and infer from this that as a subject Draughts is ap proaching exhaustion. It is not appreciated (but such is the fact) that every well-balanced and easy-looking draw between two good players is the product of long and concentrated preparatory study and analysis on strict lines of scientific method. It is neces sary for a player to keep himself informed of all contemporary analytical discoveries, or he will find his play out of date. Not withstanding all preparation, every player becomes involved in strange positions in actual games ; he then must find the best move, knowing well that nothing less will suffice. It is an intellec tual feat to draw a game at Draughts against a really fine player.

Combination.

Some of the beauties of the games are ex hibited in the following examples, each of which has been selected on account of some striking combination, brilliant idea or other artistic merit displayed.Game No. I AYRSHIRE LASSIE OPENING a11-15 25-18 I0-15 22-17 b15-18 24-6a24-20 23-19 13-22 24-20 2-9 8-II 6-I0 26-17 18-27 17-I0c 28-24 5-9 d 27-2311-16 31-24 8-II 9-13 30-26 9-14 20-II 16-23 Drawn22-18 1-5 18-9 7-16 20-16 R. Jordan 15-22 32-28 5-14 29-25 12-19 a. 11-15, 24-2o forms the "Ayrshire Lassie" opening, so named by Wyllie. It is generally held to admit of unusual scope for the display of critical and brilliant combinations.

b. 16-20, 25-22, 20-27, 31-24, 8-11, 17-13, 2-6, 2I-17, 14-21, 22-17 21-25, 17-14, 10-17, 19-I. Drawn.

Game NO. 2 PAISLEY OPENING Played between E. R. Jacques and D. Campbell II-16 17-14 16-23 25-22 20-27 23-18 24-19 10-17 26-19 7-11 14-9 14-23 8-11 21-14 4-8 19-15 7-14 21-7 28-24 11-16 29-25 12-16 9-6 3-To16-20 25-21 13-17 15-IO 1-10 26-3 22-17 6-9 31-26 2-7-a 18-9 27-31 9-13 23-18 9-13 27-23 5-14 3-7White wins.

(a) Black's "side game" has not paid him very well, and his forces are now badly divided.

No. 3 LAIRD AND LADY A classic, by J. Steel, kilbirnie, Scotland II-15 17-14 4-8 26-23 12-16 12-3 23-19 10--17 24-19 16-20 19-12 2-7 8-11 21-14 13-17 31-26-a 7-10 3-10 22-17 15-18 28-24 18-22-b 14-7 6-31 9-13 19-15 II-16 25-18 3-28 Black wins.

(a) Plausible but loses. (b) "The Steel Shot." No. 4 BRISTOL CROSS Played at Halifax, Yorkshire, between C. Horsfall (Black) and S. Greenslade (White) II-16 I2-16 16-23-a 11-16 7-I1 6-31 23-18 17-14 17-13 31-26 26-19 13-6 16-19 8-12 4-8 16-2o 3-8 1-26 24-15 22-17 28-24 25-22 12-3 30-23 I0-19 19-23 8-11 12-1 6-b 2-7 II-16 21-17 26-19 24-19 19-12 3-10 Black wins.

(a) Enterprising play. A man so thrust forward is a menace if it can be maintained. (b) Notice how the man on 23 is completely surrounded. Now begins a lovely combination.

No. 5 OLD FOURTEENTH Played at Buffalo, U.S.A., between Mugridge (Black) and Hodges (White) II-15 18-9 1I-15 26-23 28-32 7-14-d 23-19 5-14 19-16 24-28 19-15 6-Io-e 8-11 26-23 12-19 20-16 32-28 14-7 22-17 I-6 23-16 15-24 15-II 32-28 4-8 30-26-a 15-19 23-19 28-32 21-14 25-22 6-9 27-23 14-18 11-7-b 22-25 9-13 32-27 8-11 22-15 3-10 29-22 27-23 2-6 16-12 13-22 2-7 24-27 6-9 24-20 19-24 9-13 31-24 23-18 15-24 23-19 10-14 12-8 28-26 9-14 28-19 1I-15 11-2 14-17-C Black wins.

(a) Evidently this is inferior, but the subsequent play is masterly. (b) A bid for freedom. (c) Very fine. (d) Taking the other way, he would be a man down permanently. (e) This stroke removes all the White pieces from the board.

No. 6 CROSS The following is an example of a "Block": 11-15 30-26 15-19 27-24 6-10 29-25 23-18 9-13 18-14 8-12 27-23 7-I1 24-20 I0-15 25-2I 2-6 26-23 12-16 23-18 1-6 31-27 3-7 21-17 6-9 32-27 4-8 and White wins, having the last move. It is now Black's turn to play, and having no move available, he has lost. A counterpart "block" with no piece taken on either side is sure to end in a White win. The game, however, is only a freak.

General Principles.

The foregoing games are entertaining enough, but such spectacular play is rare between accomplished players, although great skill, as well as vigilance, is required to avoid falling occasionally into some subtly prepared stroke. Nov ices often lose games by stroke play—sometimes indeed they are allowed to make an inviting stroke on their own account, only to find that the resulting position runs badly against them. Strokes and combinations are used by experts as threats, and are useful adjuncts to position play, their avoidance by the opponent probably entailing some precautionary move on his part which if not entirely inferior will not improve the strength of his game. Setting traps, however, which if avoided will allow the adversary an improved position, is strictly eschewed by good players.Of general theory which can be expressed in anything like precise terms there is none. The game is not amenable to treatment by any of the methods of pure mathematics, which seems strange at first, because above everything it demands, constantly, the most exact calculation. The circumstance is fortunate. Investi gation of the possibilities and potentialities of the game depends entirely on practical analysis—actual trial and selection of moves in given positions. Such research is being carried on without ceas ing by hundreds of busy brains throughout the world, merely multiplying the available data, without getting an inch nearer any conclusion, except the probability that one does not exist.

The authors of textbooks, therefore, are chary of giving general advice, and such as they offer is obscure and sometimes contra dictory. Beyond recommending the student to play towards the centre of the board in preference to the sides they say little, pre ferring instead to recommend a plunge into the columns of fig ures (representing moves) which bulk so largely in every book on Draughts.

There are several coherent general schemes for bearing the men well understood by experienced players. (Note, however, that such schemes do not constitute anything like a complete theory of play.) The more important are: 1. Play a centre-of-the-board game, i.e., move to the middle, bringing up the side men as sup ports, and try to divide the adversary's men by driving a wedge into his formation. 2. Play to the sides, encouraging the opponent to take up a central position, but with the view of surrounding his front and undermining his supports. 3. Play to occupy the squares 14 and 19 with supported men, as such formation will attack the opposing double corner and secure one's own. 4. Play to attack the single corner by establishing a supported piece (if Black) on 18, or (if White) on 15. 5. Play to keep the game open, especially in the centre, by making judicious exchanges, and refrain from any pronounced attack or defence (especially attack).

There are other general plans, some of which cannot be quite so simply described as the above, but as the experienced player very well knows they are all subject to the qualification of if permitted or as far as may be possible and prudent. Nos. i and 2, for instance, are reciprocal to some extent, and the one may be met by the other in many cases without advantage to either. They are opposed very prettily for instance, in certain lines of the "Old Fourteenth" (I I-15, 23-19; 8-1I, 22-17; 4-8 forms the opening, usually continued 17-13, 15-18, 24-20; 11-15, 28-24; 8-11, 26-23, etc.). No. 3 was the subject of a serious attempt by the American champion, N. W. Banks, to develop a system of play as described, and he shows many applications of it in his book Scientific Checkers (1923). The idea was not original with Banks, but he carried it further than any previous writer, without much practical success, however, as his advocacy tended to make him overrate the scheme, which he recommended in some games where stronger play was demonstrable. The number 3 plan is well exemplified from Black's point of view in the "Dyke" opening (11-15, 22-17; I 5-19, 23-16; 12-19, 24-15; 10-19, etc.) . No. 4 is not as feasible as some of the others, but is developed by Black fairly strongly in the "Maid of the Mill" opening (11-I 5, 22-17 ; permitted by White, who can easily evade it). No. 5 is often the style of thing which occurs as a result of compromise or desire to keep the draw in sight : it leads to the adoption of such openings as the "Defiance" (11-15, 23-19; 9-14, 27-23 avoiding many complications con sequent on 22-17 and usually continued 8-1i, 22-18, the exchange of two-for-two leading to an open game) .

Before leaving this discussion of system the following example of the success of the second scheme when opposed to the first may be cited as worthy of more than casual examination. It is selected to show that such advice as "play to the centre" and "do not play to the sides" is not capable of universal application, but is also a splendid exposition of Draughts.

No. 7 ALBEMARLE It is uncertain who was the first to show the win in the main play of this game.

II-15 9-14-b 7-II I2-16 8-I2 9-18 22-17 25-21 3o-26-d 32-28 27-23 21-17 8-11 15-18-C 2-7 16-19-e 3-8 23-26 17-13 29-25 24-20 23-16 23-18-f 17-14 4-8 11-15 5-9 18-23 14-23 21-17-a 26-22 28-24 26-19 17-14 White wins.

(a) An uncommon opening, but the position after the next two moves can arise in several ways.

(b) The best move is 15-18—an application of scheme No. 4.

(c) Although this move is suggested by scheme No. i it loses outright. A draw is obtainable by 24-15; 10-19 (I I-18 loses) , 17-10; 6-15, 23-16; 12-19, which is according to scheme No. 3.

(d) The win is forced by a logical application of scheme No. 2. This man is the pivot of both wings.

(e) An attempt to break the cordon—the only chance.

(f) This counter sacrifice ensures the win.

To resume our consideration of general principles it is safe to say that the main thing which the experienced player keeps in view (assuming that he is opposed by an adversary of equal skill) is the probable state of his endgame, which indeed he begins tentatively to forecast as soon as a few of the opening moves have been made. Normally Draughts is a shortish game, and one or two crises quickly bring about the ending, which if not presenting some feature of difficulty may as well be declared drawn at once. To be sure of a draw, however, a player must not be in any numerical inferiority, and must be able to see his way to crown his re maining men, as any man unable to obtain a clear course is a possible source of weak ness. Strength in the end-game consists of being able to occupy the centre of the board with Kings, pinning backward men of the opponent's forces to the side squares, and preventing any Kings he may have from actively co-operating with each other. With a strong ending of such scope a player will be able to dictate replies, force advantageous exchanges, pre vent the release of the tied-up men, and eventually exhaust the moves of the last one or two badly placed pieces belonging to his opponent. The "play to the centre and avoid the sides" advice thus becomes intelligible in the ending, however doubtful of ap plication it may be in many cases earlier in the game. In the mid-game therefore the chief object is to shape an end-game with favourable possibilities. Skill to do this may only be acquired by hard practice and judicious book-work.

The End

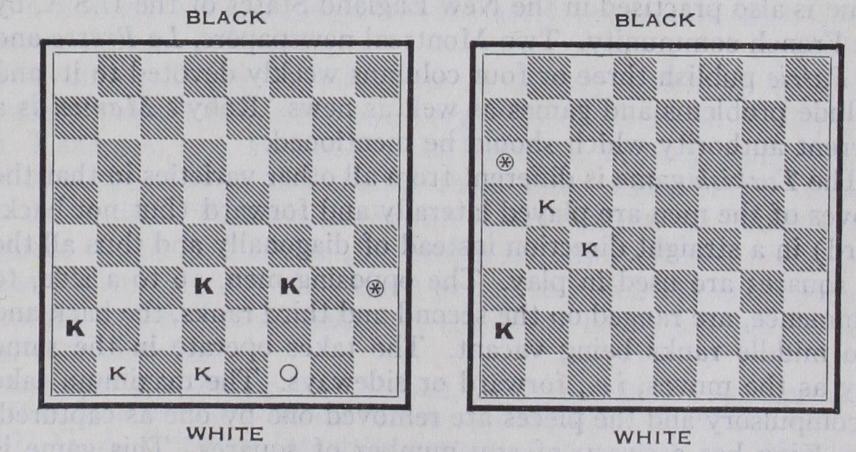

Game.—Perhaps higher qualities are required in playing for the end-game than in actually manipulating the end game when it has arrived. End-play requires great exactitude and much patience, but its principles are well known, as a number of root endings constantly recur and their handling is purely a matter of technique. Several of these root end-games have special names such as First, Second, Third and Fourth Positions, Payne's Draw, Barker's Triangle, Bowen's Twins, Strickland's Position, the Mackintosh Position, etc., etc. End-play largely depends upon calculating the influence of "the move" ("opposi tion" or "vantage" as it is sometimes called) which consists in as certaining, after pairing off the forces, piece against piece, which party will have the last move. The virtue of "having the move" is that the opponent's pieces, being obliged to give way, ultimately become confined and held unless "the move" can be altered or a defensive stronghold established.Two root endings, in which the play is not of an elementary nature, are diagramed as examples.

In "First Position" the stronger party has two Kings against King and man. The defending player has his King in the opposing double corner, and his man held up somewhere on his left wing, perhaps farther back than shown. The attacking player (who must have "the move") can drive the King out of the double corner or compel the man to advance, and this course on trial will be found to lead to the win. With the backward man on the other wing the game is drawn.

In Fourth Position the defending player is a man short, but can draw with "the move" in his favour by simple repetition. When the attack has "the move" he can construct the following situation: Black man on 21, Kings, 20, 22, 28 ; White man on 30, Kings 27, 32. Black to play wins by the sacrifice 22-26, 30-23, 28-24, etc. The single White man may be a King without alter ing the essentials.

History.

The records of the game do not go back farther than the invention of the art of printing. All conjecture as to its origin is purely speculative, and its ancient history (if any) is lost. It is not doubted that board games were played in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, but there is no evidence that such games resembled Draughts, even in rudimentary form.The Spanish authors are the oldest, dating back to the i6th century. The Spanish game to-day is the same as they then described. The early French authors treated of the form which is now generally styled the English game, but the so-called Polish game was evolved and introduced in Paris about the year 1721, superseding the older form. The Polish game spread from France to Holland, Flanders and Switzerland, and its influence is trace able in the German and Russian games. In the meantime the Italians also evolved their own special rules.

The records of English Draughts begin with William Payne (1756) and its form was permanently fixed by Joshua Sturges (r 800) . Comparatively neglected in the south of England in the beginning, it was developed successfully in Scotland and the north of England. The rise of modern master-play dates from Andrew Anderson, who retired about 185o, after playing five matches (four of which he won) with the celebrated James Wyllie, another Scotsman. Wyllie assumed the title of champion, but the honour was wrested from him by Robert Martins (a Cornishman), only to be regained. A young American named Robert D. Yates de feated both Wyllie and Martins in set matches in 1876-77, but retired, and the title reverted to Wyllie. James Ferrie (of Glasgow) finally defeated Wyllie for the world's championship in 1894. Ferrie lost by the odd game in 4o to Richard Jordan (of Edinburgh) in 1896. The latter died unbeaten in 1909 but it should be mentioned that an American champion, Charles F. Bar ker, played a drawn match with him in 19oo. The present holder and successor to Jordan is Robert Stewart of Blairadam, Fifeshire.

Organization.

The game is fairly well organized in all English-speaking countries, including the United States, but there is no supreme parliament recognized. There are many bodies such as State and county associations, and city and town clubs, Institutes and recreation clubs generally have draughts circles, and the game has a big following. All the national associations promote periodical tournaments and international team matches have been played. There is an annual British Counties' Champion ship for teams of 12 players.

Varieties of the Game.

What we have been describing is the English form of the game.The Spanish game is played in a similar manner, but with the following exceptions: (a) The board is placed with the double corner to the left (an English board in the looking-glass, as it were) ; (b) the King can move over any number of unoccu pied squares on the same diagonal; (c) It is compulsory to capture the greatest number of pieces which may be en prise at any play, which of course limits or eliminates choice when there are pieces en prise in more than one direction. The long moves of the King vastly increase his power in comparison with the ordinary man. The Spanish game, although still practised, is in a backward state and has never been properly developed. The most recent authority is Dr. M. Carceles Sabater (Madrid, i9o4)• The Italian game differs from the Spanish game (from which it was probably derived) in the powers of the King. The Italian King moves precisely the same as an English King (subject however to the maximum take being compulsory) but is immune from capture by a man. The Italian game is a very "live" proposition, and analytical discoveries in the English game are readily adapted by the Italian players. The modern authorities are G. Bassani (La Dama Scientifica, Milan, 1919) and L. Avigliano (Il Giuoco della Dama, 1918, and La Dama nel Giuoco Moderno, Milan, 1927).

The Polish game is the form most popular on the Continent.

We have already referred to its origin ; it appeared in France, but one of its earliest exponents in Paris was a Pole. It is played upon a board of i oo squares, So being used; 20 men a side; double cor ner to the right. The King (i.e., Dame or Queen) has the same powers as the Spanish King, extended to the larger board. The men, whilst moving forward as in the English game, take both backward and forward. The maximum take is compulsory, and in capturing play a man may touch the back rank without crowning if further pieces remain to be taken. The "huff" has been abol ished. The characteristic feature of the Polish game is the back ward take of the man, which players used to the English, Spanish or Italian rules find both novel and puzzling. Polish Draughts is a magnificent game, well suited to the genius and scientific bent of the French and Dutch peoples. One of the declared objects of the French Draughts Association is to convert the draughts players of other countries to the use of the ioo squared board and the Polish rules. The literature of the Polish game is voluminous, although it certainly falls short of the output of books devoted to the English game. Amongst the older French authors Manoury (about 1780) is still in good repute, and his book has been many times reprinted. Le Damier by G. Baledent (Amiens, 1881-87) is a monumental work in four volumes, and later French treatises of value which are readily procurable are those of Barteling, Chiland, Weiss, Felix Jean, etc. The best Dutch writers have produced much progres sive work, and after Van Embden (the ancient authority) should be mentioned the modern treatises of Broekkamp, De Haas and Battefeld, Springer and De Jongh. The Polish game is served by no less than four monthly magazines.

The German game is the Polish game on the smaller (8x8) board, and does not call for much special comment. The treatises of J. Dufresne and H. Credner may be referred to, but neither is very modern. This game, by the way, has some minor vogue in the United States.

The Russian game is also minor Polish, with two important dif ferences. The choice which may be exercised in capturing is free, i.e., is identical with the English rule. A man on reaching the back rank in capturing is promoted on touching the crowning square and immediately functions as a King, continuing that play as a King. "Shashki," as it is called, is immensely popular in Russia, and has a fairly good body of literature and a monthly magazine published in Moscow.

In Canada the Montreal or Quebec game is the favourite of the French-speaking people, who refer to it as "Le Jeu Canadien." It is a major form of the Polish game, with identical rules, played on a 123E12 board with 72 playing squares and 3o men aside. This game is also practised in the New England States of the U.S.A. by the French community. Two Montreal newspapers, La Presse and La Patrie publish three or four columns weekly devoted to it, and include problems and games as well as news. Roby's Manuel is a current authority which should be mentioned.

The Turkish game is different from all other varieties in that the moves of the men are played laterally and forward (but not back ward) in a straight direction instead of diagonally and thus all the 64 squares are used in play. The opposing men, 16 to a side, to commence, are ranged on the second and third ranks, the back and two middle ranks being vacant. The takes operate in the same way as the moves, i.e., forward or sideways. The maximum take is compulsory and the pieces are removed one by one as captured. The King has a sweep of any number of squares. This game is practised in the North of Africa, Stamboul and the Levant, but its literature is practically negligible, although some highly interesting mss. are in existence.

The Losing game (in English or foreign forms) is a reversal of the ordinary rules, as the name implies.