Drawing

DRAWING, the art of delineation or of portrayal by means of lines, is so primitive that its history is practically that of man. That it was practised 50,000 years ago we know but for how long before that, it is difficult to establish. Its beginnings, however, must have been early, for one of the first things a child will busy its hands with is the making of marks in the dirt, and the walls of many a schoolhouse or home stand as mute witnesses to the inherent tendency of man to draw. It is a deep-rooted instinct whose satisfaction gives great pleasure.

Early Art.

In the beginning the primitive mind with its usual groping for essentials was satisfied with simple structural lines and, at times, outlines of those objects wherein the structure was less evident. The cave-man drew his pictures of men just as the child does—with the inverted Y for the body and legs, a cross piece for the arms and a circle for the head, part of his drawing showing structure and part out line. The first of these drawings of the child are always without consideration of motion but it does not take long before, with the addition of feet, the figure is walking and soon the arms are brought to the front. Thus we see the early beginnings of the three elements which are essential to all drawing, if it is to please man who has for thousands of generations and from childhood up been trained to expect them : structure, outline and motion. (See fig. r.) In order to draw the human figure successfully the artist must first learn about its bony structure. He must master the knowl edge of the lengths of the various units and of their possibilities for movement (see DRAWING: Anatomy). But his work does not cease in this study of structure. Trees spread their branches in certain characteristic ways each of which is slightly different, and in fact each type of leaf has its own anatomy as has every animal, bird and flower. Rocks must be closely examined and their origin understood or they cannot be given the proper struc ture. The artist cannot slight this work or his drawing will be unconvincing. He must spend much time in finding out how things were put together or how they grew and why.In speaking of outline we should think first of line itself. It has been contended that "It cannot be reasonably held that one purely abstract line or curve is more beau tiful than another, for the simple reason that people have no common ground upon which to establish the nature of abstract beauty." This is, of course, false, for if there were no common ground in beauty there would be very little incentive to draw other than as a simple record. But to put into words just what this beauty consists of, is a difficult task. Fig. 2 illustrates two lines. It will be agreed that one is more beautiful than the other. One has a sure ness and sensitive taper while the other wanders in a hesitant and aimless manner without object, without character. Perhaps that is it. Perhaps a line can have character and therefore can show those beauties and weaknesses which we see in the characters of our fellows. This is undoubtedly possible, for no two men can draw a line exactly alike and cer tainly into the lines of each must creep something of the man himself (see TECHNIQUE IN ART). Therefore, beauty of line does exist but is difficult to analyze, as it is dependent upon the person ality of the artist. It may be as difficult to tell why you like one line better than another as why you like one friend better than another ; nevertheless, there is no doubt of your preference in the matter.

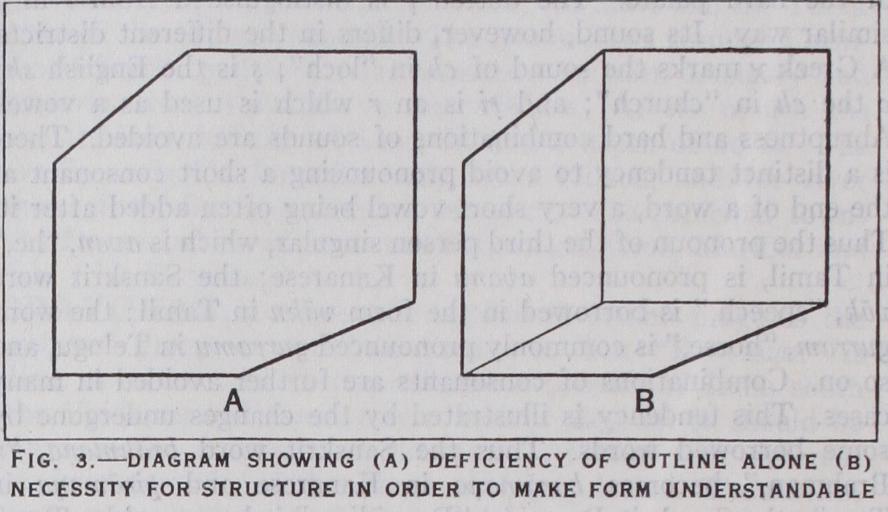

Besides this beauty of abstract line we find the age-old neces sity for outlining objects, and when asked to describe a thing our minds at once turn to its shape. Its consistency, its struc ture, its movement are all often secondary unless they assert themselves strongly. The artist has only his eyes to help him in this work but a knowledge of what lies within is also an aid to him. The author on drawing in the eleventh edition makes use of an illustration given herewith, to show how hard it often is to guess the shape of an object by its silhouette alone. (See fig. 3.) As soon as the three lines are added which indicate its structure it is obvious in shape.

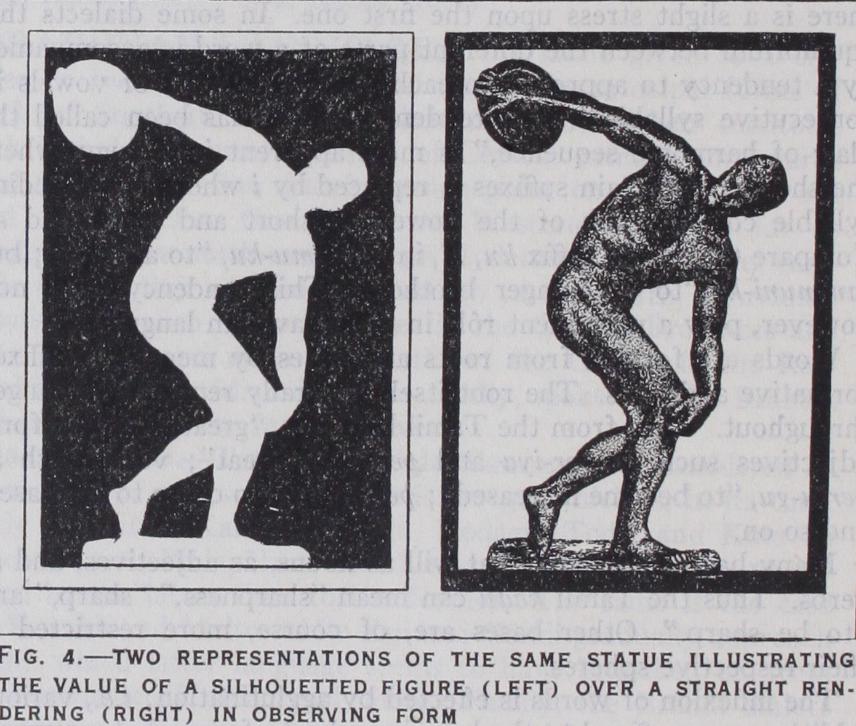

It is sometimes possible to erect an imaginary structure which is of assistance and artists frequently resort to this method. For instance, in the drawing of a vase (see fig. 5) the straight lines might be sketched in lightly and would be of some assistance in judging both curves and proportions. In other words a sort of scaffolding is first erected and then the outline drawn upon it. After a little practice the scaffolding need not be drawn for the artist can visualize it without the aid of actual lines. Another help in drawing the silhouette of an object is to reverse the idea and look at the silhouette of the background instead. This process is often employed by sculptors in their work and is undoubtedly of some assistance to them. But all of these are simply suggested aids to seeing, and it takes practice to be able to draw what one sees. (See fig. 4.)