Drowning and Life Saving

DROWNING AND LIFE SAVING. To "drown" is to suffer or inflict death by submersion in water, or figuratively to submerge entirely in water or some other liquid. As a form of capital punishment it persisted in Europe till the 18th century.

Death from drowning is the re sult of asphyxia from inhalation of water during the violent ef forts to breathe. Owing to lack of oxygen and accumulation of car bonic acid gas the blood soon be comes intensely venous and by poisoning the respiratory and cardiac centres in the medulla oblongata brings them to a stand still. Sometimes death occurs from primary syncope.

When a person unable to swim falls into the water, he usually rises to the surface, throws up his arms and calls for help. This, with the water swallowed, will make him sink. Struggling will be prolonged a few seconds, and then probably cease for a time, al lowing him to rise again, though perhaps not sufficiently high to get another breath of air. If still conscious, he will renew his struggle, more feebly perhaps, but with the same result. As soon as insensibility occurs, the body sinks altogether, owing to the loss of air and the filling of the stomach with water. The general be lief that a drowning person must rise three times before he finally sinks is a fallacy.

Before diving in to rescue a drowning person the boots and heavy clothing should be discarded if possible, and where a leap has to be made from a height, or the depth of the water is known, it is best to drop in feet first. Where weeds abound ress should be made in the tion of the stream. The danger of being clutched by a drowning man is best avoided by ing him from behind, but if seized, the rescuer must keep most, as this makes the effort of effecting a release much easier. If the rescuer be held by the wrists, he must turn both arms simultaneously against the drowning person's thumbs, and bring his arms at right angles to the body (fig. 1) . If he be clutched round the neck he must take a deep breath, lean well over the drowning person, place one hand in the small of his back and pass the other over the drowning person's arm, pinch the nostrils and at the same time with the palm of the hand on the chin push the head away with all possible force (fig. 2) . One of the most dangerous clutches is that round the body and arms or round the body only. When so tackled the rescuer should lean well over the drowning person, take a breath as before, and either withdraw both arms in an upward direction in front of his body, or else act in the same way as when releasing oneself when clutched round the neck. In any case one hand must be placed on the drowning man's shoulder, and the palm of the other hand against his chin, and at the same time one knee should be brought up against the lower part of his chest. Then, with a strong and sud den push, the arms and legs should be stretched out straight and the whole weight of the body thrown backwards. This sudden and totally unexpected action will break the clutch (fig. 3).

There are several methods of carrying a person through the water, the easiest being that ap plied to a quiescent person. Then the person assisted should place his arms on the rescuer's shoul ders, close to the neck, with the arms at full stretch, lie on his back perfectly still, with the head well back. The rescuer will then be uppermost, and having his arms and legs free can, with the breast stroke, make rapid progress to the shore (fig. 4).

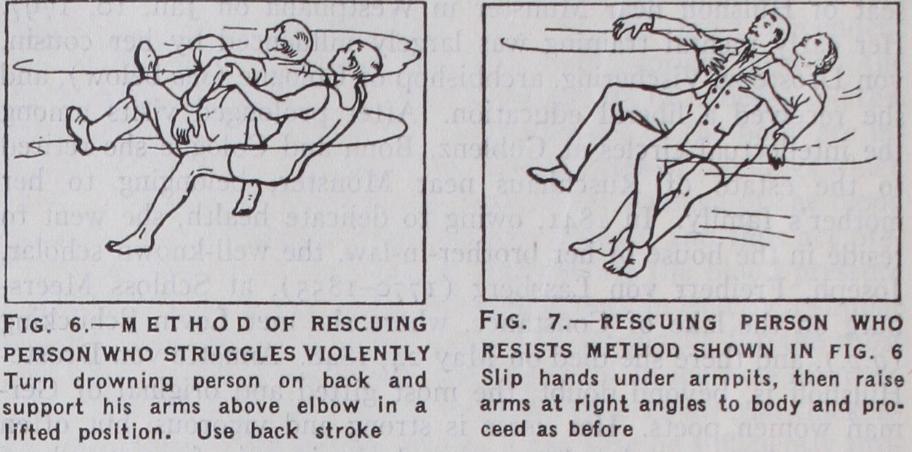

When a drowning person is not struggling, but seems likely to do so when approached, the best method is to turn him on his back, place the hands on either side of his face and swim with the back stroke, always taking care to keep the man's face above water (fig. 5). If the man be struggling and difficult to manage, he should be turned on his back as before, and a firm hold taken of his arms just above his el bows. Then the man's arms should be drawn up at right angles to his body and the res cuer should use the back stroke (fig. 6). If the arms be diffi cult to grasp, or the struggling prevent a firm hold, the res cuer should slip his hands un der the armpits of the drown ing person, and place them on his chest or round his arms, which he should raise at right angles to his body (fig. 7) . In carrying a person through the water, it is ad vantageous to keep his elbows well out from the sides, as this ex pands the chest, inflates the lungs and adds to his buoyancy. If the drowning person has sunk the rescuer should look for bubbles be fore diving in and remember that in running water they rise ob liquely. When a drowning person is recovered on the bottom, the rescuer should seize him by the head or shoulders, place the left foot on the ground and the right knee in the small of his back, and then, with a vigorous push, come to the surface.

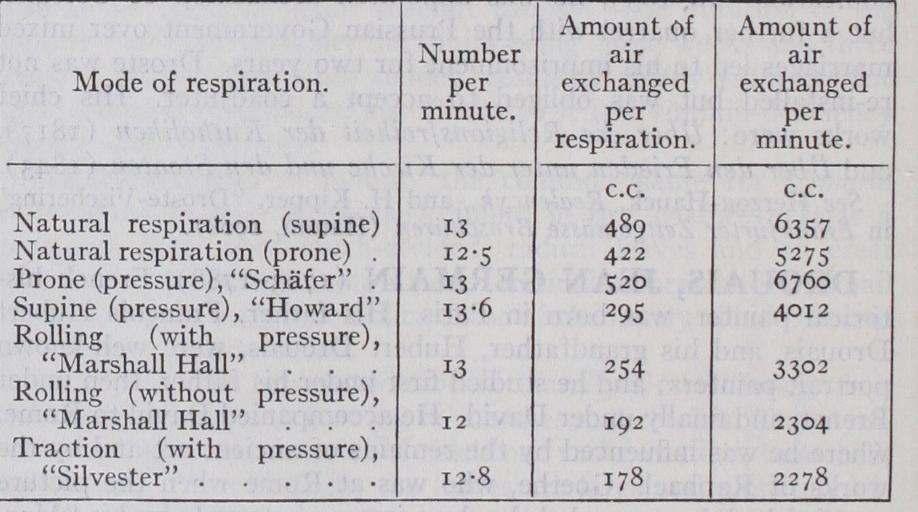

When the rescuer reaches land with an insensible person, arti ficial respiration must be em ployed. The system first in vogue (I 774 ) was inserting the pipe of a pair of bellows into one nostril and closing the other. Air was forced into the lungs and then ex pelled by pressing the chest, thus imitating respiration. About the middle of the I gth century came the methods of Marshall Hall, of Silvester, and of Howard. These have been superseded by the simpler and more effective method, worked out experimentally by Professor E. A. Schafer of Edinburgh and adopted by the Royal Life Saving Society.

Professor Schafer describes the method as follows : Lay the subject face downwards on the ground, then without stopping to remove the clothing the operator should at once place himself in position astride or at one side of the subject, facing his head and kneeling upon one or both knees. He then places his hands flat over the lower part of the back (on the lowest ribs), one on each side (fig. 8), and then gradually throws the weight of his body forward onto them so as to produce firm pressure (fig. 9)—which must not be violent—upon the patient's chest. By this means the air, and water if any, are driven out of the patient's lungs. Immediately thereafter the operator raises his body slowly so as to remove the pressure, but the hands are left in position. This forward and backward movement is repeated every four or five seconds ; in other words, the body of the operator is swayed slowly forwards and backwards upon the arms from twelve to fifteen times a minute, and should be continued for at least half an hour, or until the natural respirations are resumed. Whilst one person is carrying out artificial respiration in this way, others may, if there be opportunity, busy themselves with applying hot flannels to the body and limbs, and hot bottles to the feet, but no attempt should be made to remove the wet clothing or to give any restor atives by the mouth until natural breathing has recommenced, In his paper read before the Royal Society of Edinburgh in December, 1903, Professor Schafer gave the following table of the relative exchanges of air under different methods :— These experiments show that by far the most efficient method known of performing artificial respiration is that of intermittent pressure upon the lower ribs with the subject face downward. It is the easiest to perform, and has the further great advantage that it can be effectively carried out by one person. (See also ARTI