Dry Point

DRY POINT. Though generally classed as a variety of etch ing, and in practice often combined with that process, dry-point is, strictly speaking, a kind of engraving.

In etching the needle scratches only through the etching ground and exposes the surface of the plate; the latter is then placed in a bath of acid, and it is the chemical action of the acid that eats out in the copper a line of sufficient depth to hold printing ink. In dry-point, on the contrary, as in line-engraving, the lines are hollowed out by the tool itself in direct contact with the copper, as directed by the engraver's hand, without the interven tion of any chemical action. Zinc can be used instead of copper, but this metal wears out quickly.

Methods.

The "dry" point, so called because no bath of acid supplements its use, is a tapering pointed instrument of steel, of stronger build, than the point or needle used by the etcher and sometimes sharpened at both ends ; but many modern engravers have substituted for steel a diamond point, or more rarely a ruby, fixed in a vectal handle. With one of these instru ments the engraver works directly upon a plate of hard and polished copper, either shiny or blackened, ploughing up a line, shallow or deep, according to the amount of pressure used. Along one edge of this line, if the point is slanting, or along both edges if it is held upright, a raised edge of copper is turned up by the tool, and this ridge is termed the "burr." The burr, when the plate is inked for printing, becomes clothed with ink and produces in the impression the rich, soft and velvety effect which constitutes the peculiar charm of a dry-point proof. If the burr is removed (as it easily can be, should the engraver desire it, with a scraper) the somewhat thin line thus produced is less easily distinguished except by a practised eye, from the character istic lines produced by the burin or the etching point. The burr is delicate and is easily worn out, either by too vigorous wiping when the plate is inked (experienced printers of dry-point use the palm of the hand for wiping the plate in preference to rag or muslin) or by too great pressure in the printing press. In any case the burr does not last long and the "bloom" of the early proofs of a dry-point soon wears off. The first two or three proofs, though they may be rough and uneven, often have a charm which can never be replaced by the more even printing of the bulk of the edition, and at some stage, it may be after a dozen proofs, or 20 or 5o, according to the manipulation of the plate and the depth to which the lines have been sunk, deteriora tion inevitably becomes noticeable, unless the plate has been protected from wear by steel-facing. Some engravers assert that this precaution in no way affects the beauty of the proofs, and of some dry-point plates this may be true. But most engravers and most collectors are of opinion that there is an appreciable difference and that, according to Prof. H. W. Singer, "a trained eye can distinguish between the good, warm impressions taken from the copper and the hard, cold ones, taken from the plate after it has been steeled." There can be no doubt that dry-points printed from the steel faced plate for book illustration, such as Andre Dunozer de Segouzac's illustrations to Les Croix de Bois by R. Dorgeles (1921), can ill sustain comparison with the few artist's proofs taken before the steel-facing. In fact the process is thoroughly unsuitable for any purpose that requires the production of a large edition printed with mechanical regularity, and the dry-point only yields its essential charm in the hands of a sensitive and consci entious printer—none is better than the artist himself, if he understands the art of printing also—who knows when to stop, at the moment when the plate begins to show signs of wear, and does not feel bound to fulfil a contract by delivering a certain number of proofs, whether the plate will bear it or not. The dry-point, more than any other process of engraving, needs to be under the direct control, at every stage, of the artist who has invented the design to which he feels this process, rather than another, to be appropriate.

Corrections.

Two advantages which the dry-point process offers to the original etcher are the power which he possesses when using it of seeing exactly what he is doing with his tool upon the plate, and the comparative ease with which he can make alterations if he changes his mind or requires to correct a fault. Lines already made can be almost entirely obliterated with the burnisher or worked over with other lines, whereas in etching such alterations can only be effected by the much more difficult operation of laying a new ground. To quote E. S. Lumsden, "Corrections are very easily made in dry-point, because so little metal is removed from the surface, the strength depend ing principally upon the upturned ridges. This means that the sides of the lines are comparatively easily closed up by pushing them together with the burnisher. If the passage is to be re worked with heavy strokes, there is no difficulty at all; but if the original surface has to be recovered in order to print a clean tone from it, there is often considerable labour to erase the scratches altogether, as under heavy pressure the faintest indica tions of a line will show up in the proof. With care and patience anything can be done, and the freshness of the surface kept intact." The comparative ease with which changes can be made results, in the case of some modern original artists whose work is done in dry-point, in a multiplicity of states. Of a celebrated recent dry point by Muirhead Bone "A Spanish Good Friday," there are no less than 39 states, the engraver having repeatedly changed his mind about some detail, or thought of a fresh improvement that he could introduce, after he had begun to take proofs.

Dry-point and Etching.

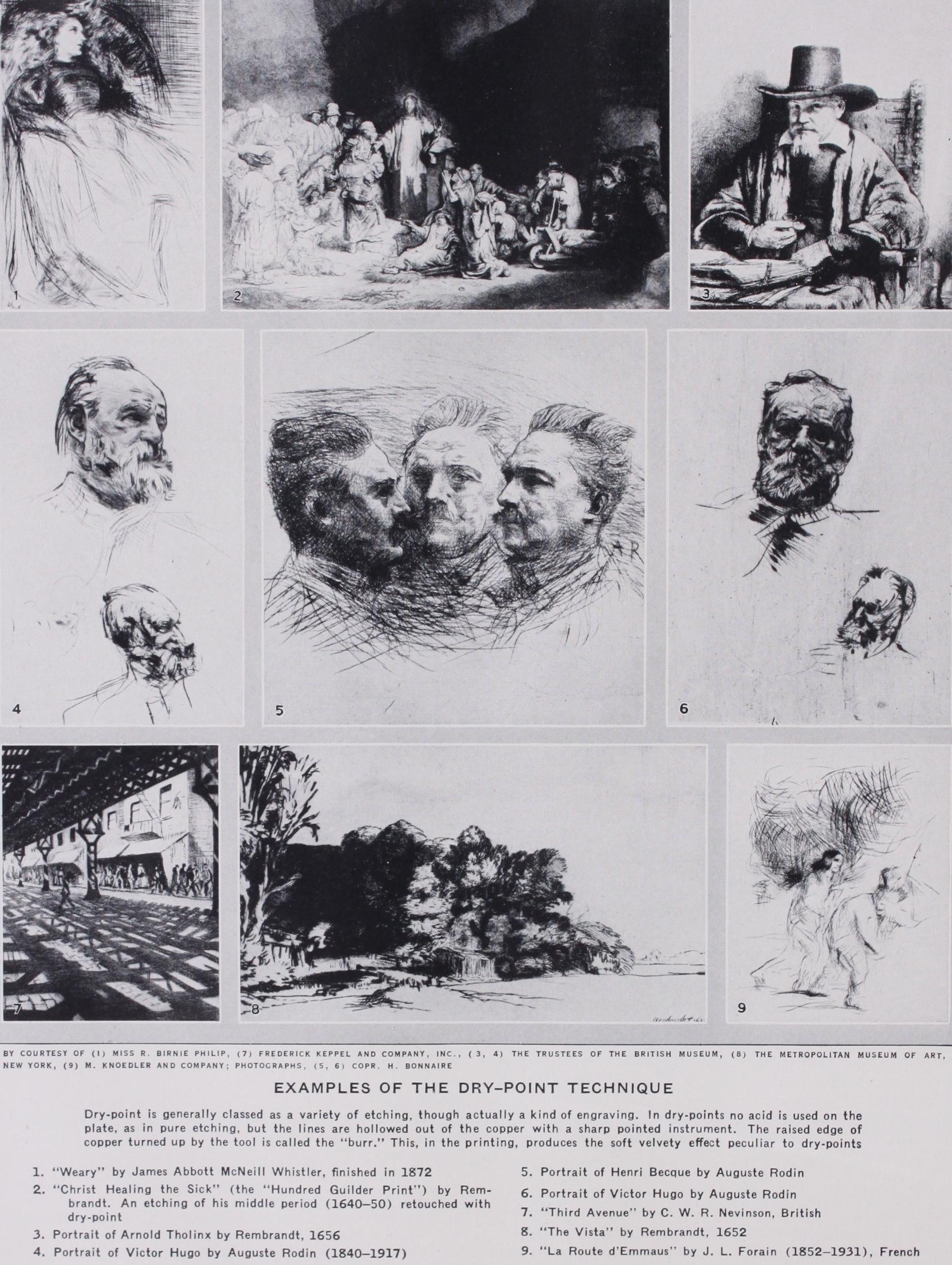

Dry-point has sometimes been used by line-engravers, instead of etching to which they far more frequently resort, in the first preparatory stage (outline) of plates which are subsequently to be finished with the burin. Much more usual is the combination of dry-point with etching. Such a combination may be made either for the purpose of the general enrichment of an etched plate, in a second or subsequent state, by the addition of the dry-point burr, or for the sake of introduc ing small corrections, which can be made far more easily, though less permanently, by the addition of a few touches or lines with the dry-point than by an additional biting of the etched plate, which involves stopping out or the laying of a fresh ground. Dry point additions to an etched plate can be readily distinguished by a trained eye in early impressions, but they wear away gradually till all trace of them is lost, and it is the presence of a clearly visible dry-point work, with all the richness that it was intended to impart, that confers value on early impressions of such an etching as the "Hundred Guilder Print" of Rembrandt, in its second state, or on the single state of "Christ Healing the Sick" by the same artist, though both the rich early impressions and the bare late ones from the worn plate which has lost its burr have to be described as belonging to the same state.In a retrospect of the use of pure dry-point during the centuries which have elapsed since the invention of engraving, it will appear that its popularity has been intermittent, and that there have been prolonged periods during which, in one country or another, if not in all countries, it has quite fallen out of favour.

Earliest Work.

Its first appearance is earlier than that of etching, for there can be no doubt that the scarce and valuable prints of the "Master of the Hausbuch," a painter-engraver who worked in western Germany (probably on the middle Rhine) about 1480, were produced with the dry-point or possibly with the burin used in the same way, so as to scratch the surface of the copper and throw up a burr, which was not scraped away. This engraver is also called the "Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet" from the fact that the largest collection of his prints, numbering about 8o in all, is in that collection, but the name is to be deprecated, as it suggests that he was a Dutchman. He was a very original artist, and a keen observer of nature, with a technique quite unlike that of any other 15th century engraver.

Diirer.

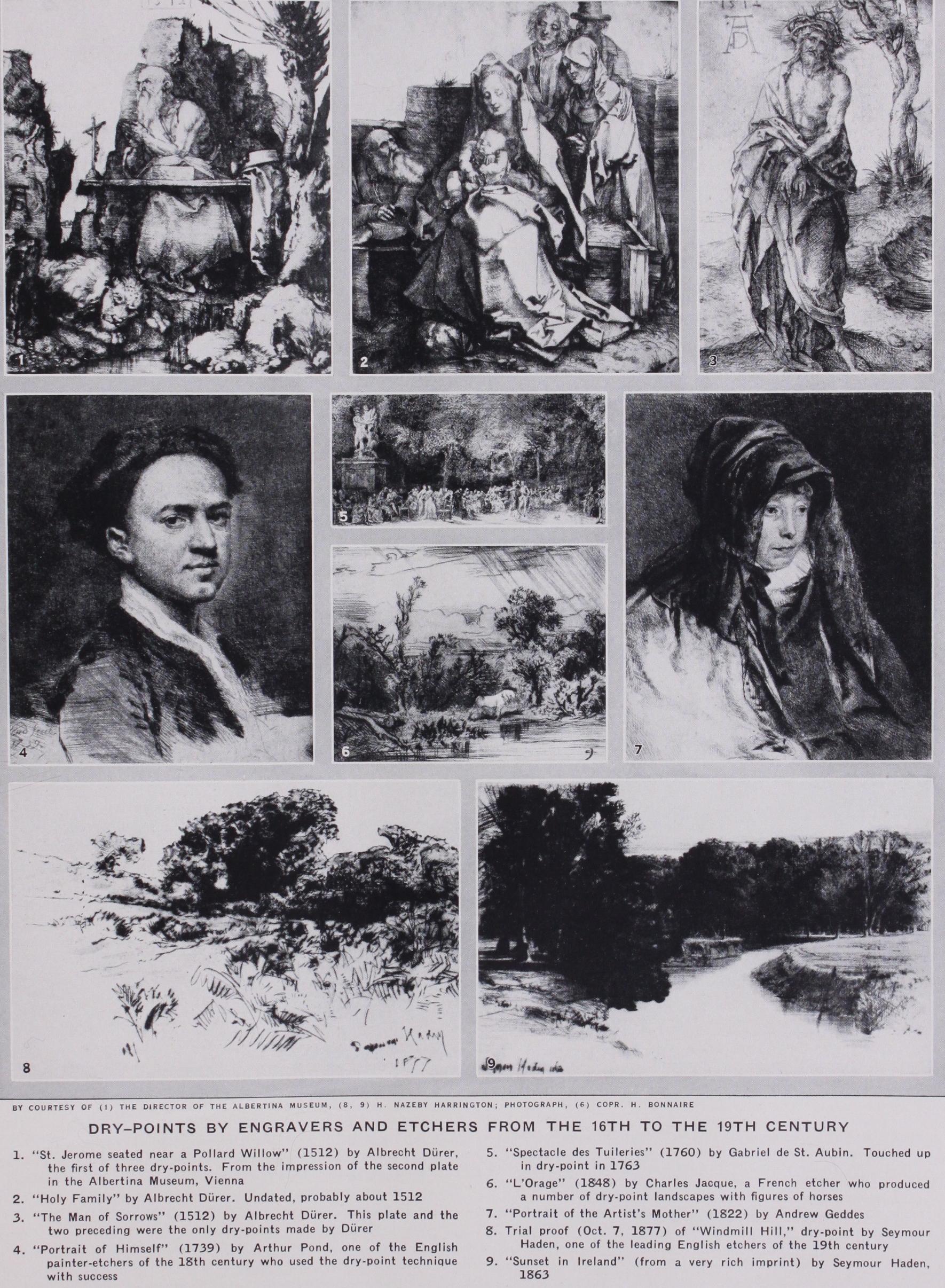

The next engraver whom we find employing dry-point is Albrecht Durer, who resorted to this process only in or about the year 1512, and probably abandoned the experiment when he discovered how few good proofs a plate engraved in this manner could yield. There are only three dry-points by Diirer, "The Man of Sorrows" 1512 (Bartsch 21, Dodgson 65), "St. Jerome seated near a Pollard Willow," 1512 (Bartsch 59, Dodgson 66), and its companion print, the undated "Holy Family" of similar dimensions (Bartsch 43, Dodgson 67). Of the two latter dry-points very few good impressions are extant, for the burr wore off rapidly and the majority of extant specimens have been taken from the worn-out plates. Of Dbrer's first work in this technique, "St. Jerome," two proofs only exist of a first state before the mono gram (in the British Museum, and the Albertina, Vienna). These are of superior quality; the Albertina impression of the second plate is also very fine indeed. A fourth dry-point, "St. Veronica" (Bartsch 64), dated 1510, which figures in the older catalogues as one of the great rarities in DUrer's work, for only two impres sions are known, is now discredited, for it has been proved to be a copy of an unsigned woodcut published at Nuremberg in a Salve Animae of 1503. Hans Sebald Beham alone of the followers of Direr used dry-point, and that but sparingly. It is hardly found again in the history of German engraving until a much later date.

Italy.

In Italy also the process was used in early times, chiefly by Andrea Schiavone, or Meldolla (1522?-82), an engraver who worked at Venice, and perhaps also by the monograminist H.E., for early impressions of his prints show signs of burr which in the usual later prints would not be suspected.

Rembrandt.

In the Netherlands dry-point was hardly used, if at all, before the 17th century. Its varied uses, as described above, for the enrichment of the etched plate by the addition of burr to the etched line as well as for the production of pure dry-points, were first discovered and exploited by the greatest of all painter-etchers, Rembrandt, who in his middle period, from about 1639 onwards, used this technique increasingly, in a thoroughly personal manner, for the sake of substituting "colour" and warmth for the drier effect of the pure etchings of his earlier period. From 1640-50 Rembrandt used dry-point extensively for retouching his etched plates—"The Death of the Virgin" and the "Hundred Guilder Print" are examples taken from the be ginning and close of this period—while in his last period (1650 61), plates wrought wholly in dry-point became more and more frequent. Among the finest of these must be reckoned "The Goldweigher's Field" (1651) ; "The Vista" (165 2) ; the two large plates, "The Three Crosses" and "Christ Presented to the People," of 1653 and 1655 respectively and the "Portrait of Arnold Iboliux," 1656. An impression of the exceedingly rare first state of this portrait, in the Rudge collection, sold at auction in Dec. 1924, realized the large sum of 3,60o guineas, the highest price hitherto paid at an auction for an etching, if not for a print of any kind.

The 18th

Century.—After Rembrandt, no very considerable use of the dry-point was made by any of the great engravers for a lengthy period. The 17th century was in all countries an age of line-engraving and etching, while in the Low Countries, Ger many and England, the invention and development of mezzotint were claiming attention. In the 18th century dry-point was used here and there by a number of painter-etchers, amateurs in their technique as compared with the professional engravers, who found the medium congenial and probably took hints in their use of it from their study of Rembrandt. A beautiful example of such an 18th century dry-point is the portrait of himself, dated 1739, by Arthur Pond (reproduced, Print Collectors' Quarterly, 1922, ix. 324). One of the little subjects illustrating the destruction by fire of the Foire de Saint Germain in 1762, by Gabriel de St. Aubin, is a dry-point which seems in its modernity a precursor of the 19th century. In the period which preceded what is known as "the revival of etching," that is to say, during the first half of the 19th century, several English and Scottish etchers produced dry-points of remarkable merit. Among these were D. C Read, of Salisbury 0790-1821), E. T. Daniell, of Norwich (1804-42), and especially the two Scottish painter-etchers Andrew Geddes (1783-1844) and Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841). Of the last two, catalogues describing all the states of their plates with repro ductions of five specimens, will be found in the fifth and eleventh publications of the Walpole Society, 1917 and 1923. Geddes' "Portrait of the Artist's Mother," his "Peckham Rye" and some other landscapes, and Wilkin's one pure dry-point, "The Lost Receipt" are of conspicuous merit if compared with the dry-points of any period. The French etcher, Charles Jacque, also produced, long before 185o a number of dry-point landscapes, with figures or horses, of great beauty.

Modern Work.

The etchers of the "revival," both in France and England soon brought the dry-point, as well as etching, into renewed favour. In the hands of Haden it yielded masterpieces like "Windmill Hill" and "Sunset in Ireland"; in those of Whistler "Finette," the "Portrait of Axenfeld," "Weary" and many more. Legros, soon after 186o, produced "La Promenade du Convales cents," "Femme se baignant les pieds," "Pecheurs d'ecrevisses," and many beautiful landscapes. His pupil, Strang, half a century later, did much fine work in dry-point; so has Sir D. Y. Cameron, especially in his later work since 1903, and especially after 1910. Another master of the technique was Theodore Roussel (1847 1926). Of outstanding excellence among French dry-points of the late i9th century are those of the sculptor Auguste Rodin, whose portraits of Victor Hugo, of Henri Becque, of A. Proust, and "Allegorie du Printemps" and "La Ronde," are among the masterpieces of the medium. The French painter and etcher, J. L. Forain, produced some superb dry-points about 1909-10 and later. Among modern British engravers, Sir Muirhead Bone is pre-eminent as a master of dry-point, in which medium almost the whole of his numerous plates since 1898 have been wrought. His brother-in-law, Francis Dodd, since 1907, has done much good work in dry-point, and among later followers Henry Rush bury has come into the front rank. Another excellent engraver in dry-point is Edmund Blampied ; C. R. W. Nevinson pro duced work of great merit in this medium during the World War.(C. Do.) Some dry-point artists use a plate prepared or blackened as for etching, taking care to cut through the varnish to the metal sur face underneath, and using the varying emphasis required by their design ; for in dry-point everything must be drawn delicately or strongly by the artist himself as in ordinary drawing. The difficulty of working on the blackened plate is that it is not easy to judge exactly what emphasis has been used in making the lines, so the bare plate is more often used and a little weak black paint rubbed into the lines to mark their progress. Great care should be taken to do such inking of the lines as gently and as sparingly as possible, as the burr is easily injured during the progress of an elaborate plate with the result that the earlier portions of the work may look quite different from the later. Another difficulty will be found in the varying degrees of sharp ness of the point used. A steel point requires resharpening fre quently and the sharpening may not be exactly the same each time and this difference will be found reflected in the work. To obviate this, a diamond or ruby point is frequently used and works very smoothly when in good condition. It is, however, somewhat brittle and apt to flake away in strong cross-hatching or by strik ing the edge of the plate.

Dry-point has several striking advantages over etching: (a) The work can be more easily judged on the bare plate, being positive in character, i.e., the lines appearing black (if filled in with black paint) exactly as in the print. (b) Corrections are more easily made as the lines are shallower and the metal being thrown up in furrows and not removed from the plate, can be forced back into the groove with a burnisher. Additions to the work can be easily made since the plate requires no regrounding and rebiting as in etching. (c) A trial print can be easily taken at any stage of the work, though it should be remembered that the fewer trial proofs that are taken the better, as a dry-point may easily be worn out in the course of a protracted series of trial proofs.

The point, the burnisher and the scraper are the three instru ments used in dry-point : the use of the scraper is of much more importance than it is in etching, as the burr can be wholly oc partly removed by it and the whole significance of the line altered. Some artists even remove the burr altogether and depend on the "nervous" character of the dry-point line for their effect.

One great disadvantage of dry-point is the difficulty of obtain ing a large number of prints of equal excellence, owing to the delicate character of the work compared with etching or line engraving. This has been largely overcome by the practice of steel-facing the plate before printing. It has led (especially in recent years) to the mixed plate, where dry-point is strengthened and stiffened by engraved lines done with the burin. The result is work obviously clearer and firmer in character than many pure dry-points, but lacking the particular charm of the best dry-point prints where spontaneity and vivacity (not characteristics of the burin) are most important assets. The best qualities of the two mediums are really incompatible. We cannot imagine a burin line introduced into the masterpieces of dry-point without fatal results. Dry-point is also used to lend to etched plates a "warmth" or "accent," or simply as the easiest method of making necessary additions. The difficulty then is that the dry-point lines wear out under the pressure of printing much earlier than the etched lines, and it becomes necessary to renew the dry-point work from time to time. From the pictorial point of view dry-point has the dis advantage of producing a picture too often "out of tone" and "spotty," owing to the somewhat accidental emphasis of the burr. From the point of view of style the dry-point needle is capable of too many different kinds of strokes; yet these difficulties only add to the fascination of trying to overcome them as they have been overcome by the great masters of the art.

Steel-facing and Printing Dry-points.

The question of steel-facing is surrounded by a prejudice in the eyes of collectors because it allows of larger editions being printed. The old steel facing was heavy and clumsy compared with what is used to-day, and must have injured the dry-point on its application. Then, too, editions used to be printed from the copper and only after that steel-faced for a commoner kind of print. And the steel-faced plate being considered "fool-proof" was handed over to unintelli gent printing—the fact not being recognized that a steel-faced plate really requires more and not less care in printing. For the delicate tones of the printing ink are more difficult to estimate with nicety on the less "sympathetic" surface of the steel. Still, it is true that for certain plates requiring delicate tones of printing-ink to supplement the line work steel-facing is not ap propriate. If steel-facing is determined on, this should be done immediately the plate is completed and it should be remembered that the cleaner the plate and its lines have been kept during work ing the better, as the plate has to be made chemically clean before the electro-steeling and the smaller the amount of cleaning re quired the better for the preservation of the burr and the delicate lines.Printing dry-points is a difficult art for the line and its burr lends itself to many different styles of printing. Care should be taken to give a clearness and purity to lines which so easily become clogged and heavy. The aim should be, while retaining the ink caught by the burr, to remove all the smudginess and heavy tone between the lines. This can best be done by repeated hand-wiping of the plate from all directions while the plate is fairly warm. Dry-point printing—or rather the preparing of the plate for the press—is thus a much slower process than etching printing, as so much more careful hand-wiping is required. "Retroussage" should be sparingly used, as the ink on the burr is easily smudged. A soft paper shows a dry-point to most advantage.

Because of its very simplicity, dry-point is a peculiarly "auto graphic" medium, very sensitive to the display of the tempera ment of the artist. All etched work bears a strong family resem blance, and still more so work with the burin. But a collection of the best dry-points shows an astonishing difference in the mere appearance of the lines. This is the great fascination of the craft, as a peculiarly personal style has been attained in it again and again. It is as capable of as many styles as drawing itself, to which indeed it is the nearest of all methods of making prints. There is no chemistry to overcome—no accidentals—the old gibe, levelled at etching, of "a blundering art" does not apply. If the student studies carefully the dry-points of Rembrandt, Whistler, Haden and Rodin, the immense range and possibilities of the medium should be clearly grasped. The inimitably natural stroke of the first, the sweeping "silky" line of the second, the abrupt strokes so suggestive of painters' colour of the third, the chisel like cutting of the fourth—there is no range comparable to this in any other system of making prints, and new triumphs of vidual method in dry-point may yet have to be recorded. (See