Dutch East Indies

DUTCH EAST INDIES The Dutch possessions in Asia lie between 6° N., off Sumatra, to I I ° 3o' S., off Timor, and from 95° E., in Sumatra, to 14o° E., in New Guinea. Politically they are divided into lands under direct government and subject Native States. The islands are described officially as of two groups, Java and Madura forming one, and the other consisting of Sumatra, Borneo, the Riouw Lingga archipelago, Banka, Billiton, Celebes, the Molucca archi pelago, the Lesser Sunda islands, and a part of New Guinea—the Outer Possessions, as they are named collectively. A governor general holds the superior administrative and executive authority, and is assisted by a council of five members, partly of a legisla tive and partly of an advisory character, but with no share in the executive work of the Government. The governor-general not only has supreme executive authority, but can of his own accord pass laws and regulations, except in so far as these, from their nature, belong of right to the home Government, and he is bound by the constitutional principles on which, according to the Regulations for the Government of Netherlands India, passed by the king and states-general in 1854, the Dutch East Indies must be gov erned. In 1916 a volksrad, or peoples' council, was established: it has advisory powers only. The governor-general must consult the volksrad on the budget, colonial loans, and the military obligations of the inhabitants. There are nine departments of administration, each under a director : namely justice; interior; education and public worship; agriculture, commerce, and indus try ; civil public works ; Government industries ; finance ; war; and navy. The administration of the larger territorial divisions is in the hands of Dutch governors, residents, assistant-residents, gezaghebbers, and controleurs. In local government a wide use is made of natives, in the appointment of whom a primary con sideration is that if possible the people should be under their own chieftains. In Surakarta and Jokjakarta in Java, in Madura, and in many parts of the Outer Possessions, native princes preserve their position as vassals; they have limited power, and act gen erally under the supervision of a Dutch official. In concluding treaties with the vassal princes since 1905, the Dutch have kept in view the necessity of compelling them properly to administer the revenues of their States, which, formerly, some of them squandered in their personal uses : the chiefs are now placed on the Civil List, their salaries, where not fixed, may not exceed 4o% of the total expenses of the State, and are raised as the revenue increases. Provincial banks have been established which defray the cost of public works. Foreign Asiatic advisors assist the Govern ment regarding the foreign Asiatic population. The sale of alco holic liquors is very strictly controlled in the Outer Possessions.

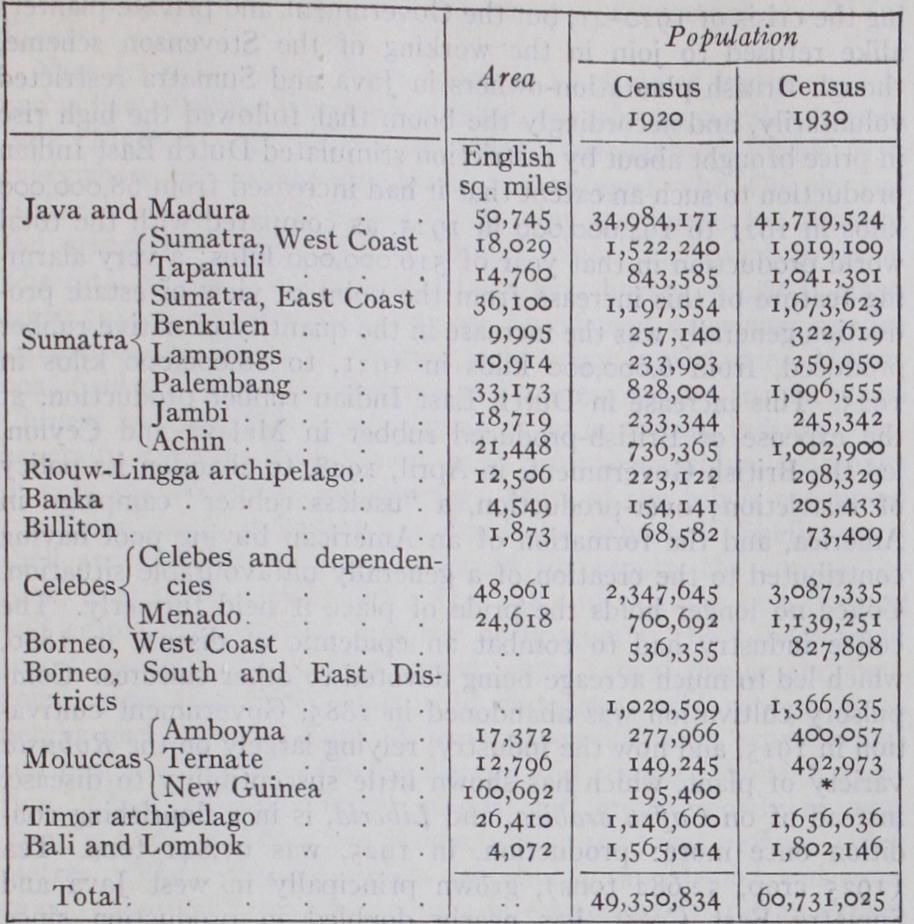

Population.

The following table gives the area and popula tion of Java and Madura, and of the Outer Possessions: Except in the case of Java and Madura, the population figures are only fairly accurate, and in some instances they are largely conjectural. The population is divided legally into Europeans and persons assimilated to them, and natives and persons assim ilated to them. The first includes Eurasians, and also Armenians and Japanese. The total number of people classed as Europeans, in 193o, was 242,372, mainly Dutch and Eurasians, a large pro portion of the Dutch being born in the Dutch East Indies. The remainder consisted of Japanese, Germans, British, French, Bel *The New Guinea population, not separately computed for 193o, included under Amboyna and Ternate.

gians and Americans. Foreign Asiatics numbered 1,344,878, mostly Chinese and Arabs, and mainly the former, but with many In dians: natives numbered 59,143,775. A large proportion of the Europeans consists of Government officials, or retired officials, for many of the Dutch, once established in the colonies, settle there for life. The remaining Europeans are mostly planters and heads of industrial establishments. The Arabs and Indians are quite generally traders ; the Chinese are also land-owners and money-lenders, whilst many are plantation labourers in Sumatra and Borneo, and in the tin mines of Banka and Billiton. The natives are mainly agriculturists'.

Religion and Education.

Entire liberty is granted to the members of all religious confessions. The Reformed Church has about 4o ministers and 3o assistants, the Roman Catholic 37 curates and 106 priests, not salaried out of the public funds. There are over Soo missionaries at work—Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Salvation Army, and their progress may be gauged from the fact that in 1896 the Christian population was 290,065 whilst in 1922 it had risen to 861,430 (739035 Protestants and Roman Catholics), exclusive of 89,199 Protestant Euro peans and 38,106 Roman Catholic Europeans. The chief Christian Church is the State Dutch Protestant Church, to which most of the Protestant Europeans belong and some 402,000 natives. Minahassa has proved the most fertile field for missionary enter prise, practically the whole population having been converted: Christianity now is making most headway in the Moluccas and New Guinea. The native Roman Catholic population is mostly in Menado, Amboyna, Flores, Timor, and the Kei and Tenimber islands. There are German, as well as Dutch missions, and some small British missionary bodies. Apart from Christian converts and the Hindu Balinese and animistic tribes in the least-developed parts of the Dutch East Indies, the natives are Mohammedan, though not generally of a bigoted type, animistic practices being often in use together with Mohammedan rites, and particularly in regard to marriage customs, inheritance, and family life in 'The density for the colony as a whole is 67 per sq.m., and for Java and Madura, 689. There is over-population in some districts in Java, and emigration to Sumatra is encouraged by the Government. Javanese coolies are employed as indentured labourers in the Straits Settlements and Malay States, also in Surinam, but few settle. Average mortality in Java and Madura is 20 per i,000. It is very much higher than this in the crowded native and Chinese quarters of the largest towns: in some coolie lines on plantations with very modern organization it has been brought down to 12 per 1,000.general. Conversion to Islam amongst the Animists means an upward step, hence Mohammedanism is gaining ground amongst such peoples. Over 20,000 natives make the pilgrimage to Mecca annually.

Both the Government and private enterprise maintain ver nacular schools. Large sums have been voted for the establish ment of primary and secondary schools, and the Government has undertaken to assist in the establishment of parochial schools, with the aim of providing one, in each village, at least in Java. There are schools for higher education in Bandung, Batavia, Surabaya, and Semarang, and schools for mechanical engineering and crafts' schools in Bandung, Batavia, and Surabaya. There are colleges for native school-masters, for sons of native officials, and special schools for native girls. Government schools exist for the European education of Chinese children and there are private secondary schools for girls. There is a Civil Service college in Batavia, a commercial school, navigation school, and training institutes for analysts and controllers of public health, pharma cists' assistants, and municipal servants. There are law colleges in Bandung and Batavia, medical schools in Batavia and Sura baya, a school for training sugar-chemists in Surabaya, a mining school at Sawah Lunto, a Higher Technical school at Bandung, and a training institution for veterinaries and an agricultural high school at Buitenzorg. The educational policy now is to increase the number of vernacular schools for the masses, develop a type of school with Dutch as the medium, for the higher classes, create secondary schools adapted to the special requirements of the country (suitable for all races), and develop higher general scientific, technical, and professional education. A Board of Edu cation was set up in 1918.

Justice and Finance.

As regards the administration of jus tice, a distinction is maintained between Europeans and persons assimilated with them and natives, together with Chinese, Arabs, etc. The former are subject to laws closely resembling those of the mother country, while the customs and institutions of natives are respected in connection with the administration of justice to the latter. The penal code, however, is the same for Europeans, natives, and foreign Asiatics, and the tendency of legislation is to make the same civil law and commercial law applicable to all sections of the community, so far as adat (custom) permits. Justice for Europeans is administered by European judges; there is a high court of justice for Europeans in Batavia, and there are courts of justice in Batavia, Semarang, and Surabaya, with authority not only over Java, but over parts of the Outer Pos sessions. For native justice there are courts in the districts and regencies; residents act as police judges; provincial councils have judicial powers, and there are councils of priests with powers in matrimonial disputes, questions of succession, etc. Also, native chiefs have extensive judicial powers in native affairs.The revenue is derived mainly from taxes on land and houses, customs and excise, a poll-tax, income-tax, land revenue and other duties; from Government monopolies, e.g., in opium, salt, tin-mines and pawnshops; from forests and from agricultural and other concessions. Until the post-war period, revenue and expenditure were fairly well balanced, and during the World War there was a large revenue margin, then, however, the general rise of prices and the pressing needs of increased transport and harbour accommodation made great demands on the public finances, and a period of deficits set in which reached a climax in 1921, when the revenue amounted to 756,000,00o and expenditure to 1,060,000,000 guilders. The funded public debt, 83,000,000 guilders in 1913, rose to 1,176,000,00o in 1923. A strong policy of retrenchment set public finances in order once more, and 1924 showed a surplus of 45,000,00o guilders, the monetary system having been maintained in such a sound condition that a return to the gold standard was possible in 1925, and this has exerted a stabilizing effect on the rate of exchange. The 1925 budget showed a surplus of 62,900,000 guilders.

The monetary system is similar to that of Holland, the unit being the guilder (is. 8d.) . It is on a gold standard, gold coins being the 5- and Io-guilder pieces. Silver is usual, i.e., 21, 1, 1, 4, and a guilder pieces. There is a five cent nickel piece, and there are copper 21, I, and 1 cent pieces. Minting is at Utrecht, in Holland. The Java Bank, established in 1828, with head quarters at Batavia, is the only bank issuing notes, two-fifths of the amount of which must be covered by specie or bullion. Gov ernment has control over the bank. There is a postal savings bank, and there are local native savings banks, and an extensive system of popular credit, i.e., village rice credit banks, village money credit banks, and divisional, or district banks. There are also ample banking facilities, European and Asiatic (Chinese and Japanese), throughout the archipelago.

Defence.

The army is purely colonial, i.e., distinct from that of the Netherlands. Its strength is slightly over 40,00o. In addi tion to this there are the legion of a native prince—Mangku Negara—of 3,60o infantry; the Barisan, or native infantry of Madura, 1,40o; the military police, nearly 1 o,000 ; and the colonial reserve and civic guard, which can be mobilized for general service. About a fifth of the regular army is composed of Euro peans, mostly Dutch, some Eurasians, and a number of Germans; the remainder is made up, in order of numerical strength, of Javanese, Amboinese, Sundanese, Buginese, and Malays. No portion of the regular army of the Netherlands is allowed to be sent on colonial service, but individual soldiers are allowed to enlist in the colonial army, and they form its nucleus. Native and European soldiers are mixed, but they are in separate com panies. Officers, with very few exceptions, are Dutch from Hol land, or colonial born. The artillery comprises field, mountain and siege batteries, with magazines, arsenals, and workshops. There is a cavalry force, and a flying corps. Recent revolutionary activity has led to budget provisions for an enlargement of the army in all its fighting branches, and other new measures of a protective nature. The Department of War is at Bandung, the military headquarters, with training schools, cavalry depot, motor artillery depot, air service depot, artillery construction shops, pro jectile factory, pyrotechnical factory, war stores depot, and a strong garrison. There is a strong garrison in Achin, and a fairly strong one in Borneo and Celebes, whilst troops are stationed at many points in Java and Sumatra, and in Amboyna and Ternate, Timor and New Guinea.The naval service of the colony has two branches, the Indian Military Marine, and the squadron of the Dutch royal navy. The former is administered by the governor-general and the Netherlands India Marine Department ; the latter, while at the disposal of the governor-general, and maintained by him during its stay in Eastern waters, is administered by the Dutch minister of marine. The Indian Military Marine consists of four old gunboats, nine torpedo boats (mostly old), and five survey vessels. The usual squadron of the Dutch royal navy is four armoured ships and six torpedo-boat destroyers.

Agriculture.—The agricultural industry is divided into two distinct groups, estate agriculture and native agriculture: the former is purely for export ; the latter mainly to provide the necessities of life, though there is extensive native cultivation of rubber, coffee, tobacco, cassava (tapioca), kapok, pepper, ground nuts, coco-nuts and maize for export. Estate land may be lease hold, from the Government or from native rulers; rented volun tarily from native owners (with restrictions to protect native in terests); or private lands, dating from the time of the East India Company, with manorial rights, but these are gradually being re purchased by the Government. Estates are mostly European owned and are situated mainly in Java and Sumatra. The main native-grown products are : rice, maize, cassava, sweet potatoes, soya beans, ground-nuts, sugarcane, cassia, cloves, nutmegs, pep per, tobacco, coco-nuts, rubber, coffee, tea, kapok, cotton, betel nuts and native fruits and vegetables of many kinds ; estate products are : sugar-cane, rubber, coffee, tea, tobacco, chinchona, coco-nuts, agava fibres, cocoa, coca, palm-oil and lemon-grass. Rice is the chief native crop, maize comes next in importance, then cassava. Sugar is the chief estate product, grown principally in east and central Java. The yield is high and the quality first-class; the sugar is manufactured locally, in mills equipped with the latest scientific appliances. Production, in 1925, was 2,300,000 tons. Rubber is second in importance, the industry suffered heavily dur ing the crisis of 192o-21, but the Government and private planters alike refused to join in the working of the Stevenson scheme, though British plantation-owners in Java and Sumatra restricted voluntarily, and accordingly the boom that followed the high rise in price brought about by restriction stimulated Dutch East Indian production to such an extent that it had increased from 68,000,000 kilos in 1921 to 194,000,00o in 1925, as compared with the total world production in that year of 516,000,000 kilos; a very alarm ing feature of this increase from the point of view of estate pro duction generally was the increase in the quantity of native rubber produced, from 6,000,000 kilos in 1921, to 88,000,000 kilos in 1925. This increase in Dutch East Indian rubber production, at the expense of British-produced rubber in Malaya and Ceylon, led the British Government, in April, 1928, to abandon its policy of restriction; over-production, a "useless rubber" campaign in America, and the formation of an American buying pool having contributed to the creation of a generally unfavourable situation. Coffee no longer holds the pride of place it held formerly. The coffee industry had to combat an epidemic of disease in 1880, which led to much acreage being devoted to other cultures. Com pulsory cultivation was abandoned in 1885, Government cultiva tion in 1915, and now the industry, relying largely on the Robusta variety of plant, which has shown little susceptibility to disease, instead of on Co ff ea arabica, and Liberia, is in a flourishing con dition once more: production, in 1925, was 97,841 tons. Tea (1925 crop, 52,682 tons), grown principally in west Java and Sumatra East Coast, has nearly doubled in production since 1921. Tobacco is grown mostly in Sumatra (East Coast) and east Java, the former being of superior quality: 1926 produc tion was 37,240 tons. Java, alone, produces more than 9o% of the chinchona placed on the market, grown in west Java, with a few estates in Sumatra. Palm oil is a very recent cultiva tion, principally East Coast Sumatra, but it has passed the ex perimental stage and is looked upon as one of the most promising of Dutch East Indian industries. Kapok, another fairly recent cul ture, has risen from about 3,00o tons in 1900 to 17,722 tons in 1926, the Java product being termed the best on the market. Copra (1926 production, 372,924 tons) may be termed the "main stay" of the archipelago, for it is produced everywhere, and, by ensuring a sure supply of cargo, enables steamers to call at very small ports and yet engage in profitable trade : coco-nut cultiva tion, estate and native, is increasing steadily. Agava fibre cultiva tion is making headway in Java (Java sisal and Java cantala), and in Sumatra, and there has been, during recent years, a very large extension of cassava cultivation, which has made the Dutch East Indies the most important tapioca-products' producer in the world. The output increased from 91,0J3 tons in 1921 to tons in 1925. Other important products are pepper (1925-28,965 tons), which is grown chiefly by Chinese and natives, in the Lampongs, Achin and west and south-east Borneo; spices, espe cially mace and nutmeg, grown in Java, Sumatra, the Moluccas, and, wild, in New Guinea; and cubebs; and essential oils, i.e., citronella, lemon-grass, patchouli and cajeput, a small crop, under 2,000 tons annually, the two first-named grown mostly in Java, patchouli in Sumatra and cajeput principally in Buru and Ceram. Guttapercha is also produced in small quantities. Forced labour exists no longer in the Dutch East Indies. Labour is cheap and plentiful in Java, and Javanese, with Chinese and other immi grants, aid cultivation in Sumatra, which, however, could absorb a good deal more. Elsewhere in the archipelago, in parts of Menado, the scanty labour supply makes agricultural develop ment possible by very slow stages only, and European capital fights shy of the uncertain situation. There can be little further expansion in Java ; Sumatra is next most favourably placed for expansion, then Borneo and Celebes, whilst the islands of the Timor group and the Moluccas will probably increase in produc tiveness gradually without much European aid, owing to their comparatively small size and increasing sea trade facilities; Dutch New Guinea, with its very scanty and quite unwilling-to-work Papuan population, must remain an agricultural problem for the Dutch for some considerable time. The Government aids agri culture by means of irrigation and in every manner possible, maintaining agricultural training colleges and experts, experi mental stations and advisors and keeping a constant watch for disease.

Next to agriculture, cattle breeding is of great importance in native life. Horses, cows and buffaloes are raised generally, hogs in Bali. Madura and Bali cattle, being thoroughbreds, rank first, everywhere the indigenous breeds are crossed with Ongole and Hissar bulls, in order to obtain heavier specimens for draught and slaughter. Thoroughbred Dutch cattle are raised in Java. The total export of live-stock in 1925 was : horses, 7 29,864 ; cows, and buffaloes, An efficient veterinary service safeguards the industry. Fishing is of equal importance. Motor boat fishing is done by Japanese in Javanese waters, in places the Chinese have worked up sea-fishing as an important industry, but generally speaking it is carried on in primitive fashion, by means of nets and traps and by spearing. Most of the fish is consumed fresh, but large quantities are dried and exported. Shells, pearl shell and tortoise shell are collected for export, the amount of each, in 1926, was, in order: 1,85o, 448 and 28 tons; also trepang and edible birds' nests. Another occupation is the collection of forest products, i.e., timber rattan, gums (copal damar and ben zoin), sago, bird-skins, atap, wild cinnamon, wild rubber, gutta percha and gutta jelutong. A forestry service, with experimental stations, watches over forest interests and restricts timber extrac tion. Chief amongst timber woods, and grown mostly in west Java, is teak, of which the production in 1925 was 248,00o cubic metres. Other valuable woods are ebony, sandalwood and iron wood, ebony averaging 8,000 tons in export, whilst rattan export in 1926 amounted to 44,568 tons.

Mining.—Reference has been made to the minerals of the Dutch East Indies. The mining industry is controlled by a Bureau of Mines, which grants prospecting licences and concessions, on certain terms, for all minerals other than anthracite and all kinds of bituminous coal and lignites, petroleum, asphalt and all other kinds bituminous substances, solid as well as liquid and in flammable gases, with iodine and allied substances. Coal is mined by the Government at the Ombilin mines, near Sawah Lunto, in the Padang highlands, Sumatra, the Bukit Asem mines, at Tanjong, Palembang residency, Sumatra and on the island of Pulau Laut, off the south-east coast of Borneo. Production in 1925 was just under a million tons. Government exploitation of coal is proceeding near the south coast of Bantam, in Java, where another important mine-field may be established. There are private concerns work ing coal in Sumatra and Borneo, with a production in 1925 of nearly 5oo,000 tons. Most of the coal is consumed locally. Tin is mined by the Government on the island of Banka, which yields exceedingly pure tin, 99.9%, and more, the balance being iron. Banka production, 1925-26, totalled 336,75o piculs (I picul= 136 lb.). There is a large private tin-mining industry on the island of Billiton, in which Government has five-eighths of the profits, production 162,70o piculs, and another at Singkep, in the Riouw archipelago, production 16,103 piculs (1925-26). There are Gov ernment-owned gold and silver mines in Sumatra which produced (1925) gold valued at 550,281 and silver at 1,608,198 guilders. The total production of gold in 1925 was 6,300,45o guilders, and of silver, 2,776,953 guilders. Dutch Borneo yielded diamonds totalling 667 carats. Petroleum is worked in south and east Borneo, Palembang Achin and the east coast, in Sumatra, in Semarang and Surabaya, Java and in Amboyna. The principal company, which controls almost the whole manufacture and out put of the Dutch East Indies, is the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company. The output of crude petroleum and of petroleum gas for 1925 was, respectively, 3,066,161 tons and 411,908 tons. Petroleum exports are in the form of kerosene, benzine, gasoline, liquid fuel, solar and Diesel oil, paraffin and lubricating oils; paraffin wax is made, also batik wax. Asphalt deposits are being worked in the island of Buton, south-east Celebes.

Industry, Trade and Commerce.—Industry in the Dutch East Indies is still in the first stage of development, but, apart from the industries connected with the manufacture of cane-sugar, rubber, tea, chinchona, cocoa, essential oils and cassava products, and the petroleum and tin-mining industries, there are soap, ice, cigar and cigarette, aerated waters, cement, sulphuric acid, oxygen and explosives factories, paper mills, machine repair, metal con struction, paint and varnish, tin packing, cement and brick and tile works, alcohol and arrack distilleries, potteries, tanneries, rice mills, coco-nut oil mills, lime kilns and cement tile factories, most in European, some in Chinese hands ; whilst the native plaited hat industry of Java produced, in 1925, 2,960,00o bamboo and o,000 pandan hats, shipped to foreign ports, and the native batik industry is very large.

Retail trade is carried on in native markets, and is almost entirely in native hands; Chinese and Arabs, with a few Indians, act as intermediaries. Wholesale trade is largely in European hands, but there are many Chinese and Japanese wholesale trade organizations. There are many trading associations, and chambers of commerce, and there is a Government Department of Agricul ture, Commerce and Industry. There are import and export duties of a nature purely fiscal. Total imports for 1925 were 862,584,00o guilders, and exports 1,813,348 guilders. Principal imports were: textiles, 252,808,000; rice, 74,9oi,000; iron and steel goods, 52,560,000; machines and tools, 47,433,OOO; manures, 18,071,00o and yarns, 14,847,00o guilders; whilst principal exports were rubber, 582, 21 o,000 ; sugar and molasses, 369,488,000 ; tobacco, II0,471,000; copra, IO2,392,000; tin and tin-ore, 859,000; tea, 74,370,000; coffee, 68,277,00o; pepper and cubebs, 24,460,000; kapok, 2I,630,000; tapioca and sago, 16,974,000; agava fibres, 14,704,000; essential oils, 13,S78,000; chinchona bark and quinine, 12,346,000; gums, Io,014,00o and hides and skins, 9,961,00o guilders. Dutch imports were British, I23,505,000; German, 58,974,000; American, and British-Indian, 41,888,00o guilders, whilst next were Italy, Belgium and Switzerland. Of the exports, Singapore took 476, 145,000 ; Holland, 2 7 5,905,000 ; the United States, 2 51,398,000 ; British India, 143,440,000; Great Britain, 122,003,000; Japan, France, 55,854,000; China, 52,293,000; Hong Kong, 48,696,000; Penang, 38,565,000; Germany, 37,865,000; and Aus tralia, 3 5,62 5,00o guilders.

Shipping and Communications.—The principal steamship company operating almost exclusively in the archipelago is the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatscliappij (the Royal Packet Naviga tion Company) which has 65 passenger and 45 freight boats, with one salvage vessel. Half the tonnage in Dutch East Indian waters is under the Dutch flag, other chief companies being the Nether lands Steamship Company and Rotterdam Lloyd, plying between Europe and Java ; and of other tonnage, British ships are by far in the majority. There are frequent services between ports in Java and Sumatra and ports in the Straits Settlements, Australia, India, China, Japan, Europe and America; and Royal Packet vessels ensure constant communication between Java and Sumatra and the rest of the archipelago. The total length of rail and tramways is 5,394 km. in Java, 1,673 in Sumatra and 47 in Celebes. The revenue in 1925 was 119,92 2,00o guilders. An air service between Batavia and Surabaya and one, carrying mails, between Amsterdam and Batavia is in operation. Good motor roads exist in most parts of Java, and in some parts of Sumatra, and there are a number of motor services which link up with rail and tramways. There are few roads elsewhere. Good cable and land telegraph services exist, except in the remote islands; Java has the most powerful wireless station in the world at Bandung, and stations at Sabang, in Sumatra, Kupang, in Timor, Amboyna, in the Moluccas, Macassar, in Celebes and at Merauke, in south west New Guinea. Java has a very extensive and most efficient telephone service (by the beam wireless system this has been linked up with Amsterdam and London), so also have some towns and districts of Sumatra, Celebes and Menado, Borneo, Amboyna, Bali and Lombok. There is no regular programme of broad casting, but a local syndicate in Java has applied for the broad casting rights. Electric light and power is available in Java and Sumatra at all large centres, and in many of the chief centres of the Outer Possessions; water-power is being developed.