Dyeing

DYEING. The art of colouring textile and other materials in such a way that the colour appears to be a property of the dyed material and not a superficial effect such as that produced by painting. The result of a dyeing operation may be regarded as satisfactory and the substance can be truly termed dyed when the colour is not removed by rubbing or washing or by the action of light. Comparatively few colours pass all tests to these influences; other types of fastness such as resistance to perspiration, street mud, bleaching and finishing are frequently required, and dyeings are approved if they meet some specific demand. A coloured effect, which is comparatively slight con sidering the amount of colour required to produce it, is regarded by the dyer as a worthless stain. Such stains are produced by dipping fabrics in the aqueous extracts of many fruits and flowers. It is natural to suppose that a desire to transfer the beautiful colours of these substances to textile fabrics may have been the origin of dyeing, but the art is such an ancient one that this is mere conjecture.

Fabrics found in the tombs of Egypt prove that those who dyed them must have been expert in the application of substances which do not immediately reveal their colouring power, but must be associated with other products in a manner which admits of variation only within well defined limits. The dyeing of red with madder or some allied product and of blue with indigo are processes which appear to have been familiar to the people of India, China, Persia and Egypt several thousand years before the Christian era. Some information regarding the dyeing processes used was evidently communicated to Europeans by Phoenicians and Alexandrian merchants, but possibly owing to the state of barbarism which followed the civilizations of Greece and Rome records of the methods practised by these people are very scarce. Pliny gives a description of the dyeing of Tyrian purple and some other colours. In the early period of its development dyeing was probably a home industry carried on mainly by women.

In the 13th century there was a notable revival in the art, for a Florentine named Federigo discovered how to prepare and use certain lichens found in Asia Minor for the dyeing of purple. For this he was awarded great honour and the privilege of adopt ing the family name Rucellia. (The lichen he used was Roccella tinctoria.) In 1429 the first. European book on dyeing was pub lished at Venice, Mariegola dell'arte de tentori. After that time knowledge of the subject spread to Germany, France and Flanders, from which latter country the English king Edward III. procured dyestuffs for England and a Dyers' Company was incorporated in 1472 in London.

The discovery of America in 1492 and the opening up of the Cape route to the East Indies resulted in new products (dye woods) and new methods of dyeing being used in Europe. In 1518 the Spaniards imported cochineal from Mexico where they had observed the natives employing the insects for dyeing. It is of interest to note that the Incas were skilled in the art of dyeing, but how they acquired the knowledge is unknown. In 163o a Dutchman named Drebbel discovered how to obtain a brilliant scarlet on wool with tin and cochineal. The process was com municated to other dyers, and the new scarlet was dyed as a specialty at the Gobelin works in Paris, and, in 1643, at a dye works at Bow, near London.

On the initiative of the Royal Society, the first English book on dyeing entitled An apparatus to the history of the common practices of dyeing was published in 1662. In France much at tention was given to the promotion of the art by the various ministers of State. Colbert published a code of instructions to wool dyers and manufacturers, but the greatest service was ren dered by a number of eminent chemists who investigated the processes in vogue and attempted to explain and improve them. In different ways Duf ay, Hellot, Macquer, Berthollet, Roard and Chevreul in France, and Henry, Home and Bancroft in England did much to improve the methods of dyeing and to establish the industry on a more systematic basis. During this period (1700 1825) a number of important chemical products were introduced and prejudice against the use of dyewoods was overcome. It was not until the middle of the igth century that dyers began to consider the possibility of using coal-tar products for their work. In 1856 the first colour made from coal tar dyed wool and silk directly but could not be applied to cotton until Perkin and Pullar devised the method of tanning and fixing the tannic acid with tartar emetic, before immersing the cotton in the colour solution.

As early as 1834 Runge had conceived the idea of producing colour on the fibre by the oxidation of aniline, but it was the Accrington chemist Lightfoot who, in 1859, discovered the cata lytic action of copper, in using sodium chlorate to oxidize aniline on cotton fabric, and produced a black by this method. The method of dyeing cotton with a solution of colour in sodium sulphide was introduced with the colour cachou de Laval in by Croissant and Bretonniere.

The substitution of naturally occurring substances used in indigo dyeing commenced about the middle of the 18th century with the introduction of ferrous sulphate (copperas) and lime. In 1845 the zinc-lime vat was first used, and for many years it was the most important vat for dyeing cotton. It reduced the loss of indigo from 20 to i o%; and the time occupied in waiting for the sediment formed in the copperas vat to settle was saved, the zinc vat clearing quickly. A product of outstanding im portance is sodium hydrosulphite discovered in 1868 by Schut zenberger and Lalande. Its use was suggested by these chemists in 1872, but it was some time before any extensive use was made of the discovery. Some dyers prepared calcium hydrosulphite in solution for themselves, with sodium bisulphite, zinc dust and lime, but in 1897 the Badische Anilin and Soda Fabrik offered to dyers a commercial product which produced a clear solution of indigo white in the presence of alkali without sediment. This was improved by the solid white anhydrous sodium hydrosulphite, which was put on the market in 1903. Hydrosulphite, as the product is generally called, is extensively employed in the dyeing of vat colours. It might be dispensed with, if colours of the indigosol (192 2) and soledon jade green type were less expensive.

One of the most interesting and valuable dyeing processes was discovered in 188o by R. Holliday. This was the formation of para-nitraniline red on cotton, a process which soon achieved great importance and formed a basis for the production of a range of allied colours on cotton (insoluble azo colours). Dyeing by this method has been greatly assisted by the introduction of the intermediate products such as Naphthol A.S. (I 912), which yields faster colours. The rapid fast colours are admixtures of this with stabilized diazo compounds. These can be applied directly to cot ton and produce the colour on the fibre by steeping in hot dilute acetic acid.

It is to Mercer and Greenwood that we owe the discovery of the effect of sulphuric acid on oils in producing more satis factory results in turkey-red dyeing than could be obtained with the oil emulsions. Turkey-red oil, sulphated oil and allied prod ucts have found extended application in dyeing since the intro duction of acetate silk. The study of their influence on the fastness of dyed colours is important. J. R. Hannay and F. W. A. Ermen have contributed to this knowledge concerning sulphur and vat colours respectively.

General Principles.—The art of dyeing is a branch of applied chemistry in which the dyer is continually making use of chemical and physical principles in order to bring about a permanent union between the material to be dyed and the colouring matter applied. If cotton or wool is boiled in water containing finely powdered charcoal, or other insoluble coloured powder, the mate rial is not dyed, but merely soiled or stained. This staining is entirely due to the entanglement of the coloured powder by the rough surface of the fibre, and a vigorous washing and rubbing suffices to remove all but mere traces of the colour.

There must always be some marked physical or chemical affinity existing between fibre and colouring matter, and this de pends upon the physical and chemical properties of both. It is well known that the typical fibres, wool, silk and cotton, behave very differently towards the solution of any given colouring matter, and that the method of dyeing employed varies with each fibre. As a general rule wool has the greatest attraction for colouring matters and dyes most readily; cotton has much less attraction, while silk occupies in this respect an intermediate position. These differences may be to some extent due to dif ferences of physical structure in the fibres, but they are mainly due to their different chemical composition. Many processes and treatments to which textile fibres are subjected yield materials which show very different dyeing properties from the original substance.

Dyeing processes may be classified under the following head ings .

I. Direct dyeing, using (I) Basic colours for animal fibres and acetate silk.

(2) Acid colours for wool.

(3) Direct cotton colours for both vegetable and animal fibres.

II. Dyeing with reduced colour solutions in (I) Sulphur colours.

(2) Vat colours.

III. Mordanting and dyeing, usingIii. Mordanting and dyeing, using (I) Basic colours for cotton.

(2) Mordanting with metallic compounds and dyeing.

IV. Producing colours on the fibre. Mainly used for vegetable fibres.

(I) Aniline black.

(2) Insoluble azo colours.

(3) Mineral colours.

Direct Dyeing.

This is the simplest of all dyeing operations. It is most successful in the case of animal fibres, wool showing such a decided affinity for both acidic and basic organic com pounds which possess colouring power that a very numerous selection of colouring matters is possible.(I) Wool is dyed with basic colours directly from a neutral aqueous solution (without additions) the wool combining with the colour base to form a coloured salt or lake on the fibre. Although a neutral dyebath may be employed, an addition of 2% soap gives a brighter colour, and in some cases acid is added to the bath. Silk is dyed in a bath containing boiled off liquor; 2 to 3% on the weight of material is usually necessary.

Acetate silk has such a remarkable affinity for organic com pounds of a basic character that it is capable of combining with these under a variety of circumstances. The basic colours act as direct dyes for acetate silk and some (brilliant green, for example) show better fastness on this than they do on tanned cotton. Amino azo and insoluble basic dyes converted into their car boxylic acids dye acetate silk. The compounds of insoluble organic bases with the omega sulphonic acid group are soluble colours, ionamines, which dye acetate silk in the presence of formic or sulphuric acid. Some can be diazotized and developed on the fibre.

Insoluble basic compounds in a dispersed or colloidal condi tion with sulpho-ricinoleic acid (soluble oils) dye acetate silk direct at 8o°C. (S.R.A. colours). Other colours employed in this way are amino anthraquinone derivatives (duranol, celatene and dispersol colours).

(2) The acid colours are applied to wool in this way because it is necessary to modify the composition of the fibre to render it capable of uniting with the colour acid of the dyestuff. Wool boiled with dilute sulphuric acid and then thoroughly washed with boiling water until free from acid acquires the property of dyeing with acid colours even in neutral solution. The at ount of colour used is from 2 to 6% on the weight of the wool with 25% sulphuric acid (1.84 sp. gr.) and i o% sodium sulphate (Glauber's salt). The last addition is made to produce level dye ing for it exerts a restraining action. This is also effected by the use of old dye liquors, a diminished amount of acid, the employ ment of weaker acids, acetic or formic acid or ammonium acetate and entering the material at a low temperature.

The woollen material is introduced and continually handled or moved about in the solution, while the temperature of the latter is gradually raised to the boiling point in the course of a to I hour; after boiling for to 2 hour longer, the operation is complete, and the material is washed and dried.

In the application of alkali blue the process of dyeing in an acid bath is impossible, owing to the insolubility of the colour acid in an acid solution. Wool and silk, however, possess an affinity for the alkali salt of the colouring matter in neutral or alkaline solution, hence these fibres are dyed with the addition of about 5% borax; the material acquires only a pale colour, that of the alkali salt, in this dyebath, but by passing the washed material into a cold or tepid dilute solution of sulphuric acid a full bright blue colour is developed, due to the liberation of the colour-acid within the fibre. In the case of other acid colours, e.g., chromotrope, chrome brown, chromogen, alizarin yellow, etc. the dyeing in an acid bath is followed by a treatment with a boiling solution of bichromate of potash, alum or chromium fluoride, whereby the colouring matter on the fibre is changed into insoluble oxidation products or colour lakes. This operation of developing or fixing the colour is effected either in the same bath at the completion of the dyeing operation, or in a separate bath.

When dyeing with certain acid colours, e.g., eosine, phloxine and other allied bright pink colouring matters derived from re sorcin, the use of sulphuric acid as an assistant must be avoided, since the colours would thereby be rendered paler and duller, and only acetic acid must be employed.

The properties of the dyes obtained with the acid colours are extremely varied. Many are fugitive to light; on the other hand, many are satisfactorily fast, some even being very fast in this respect. As a rule, they do not withstand the operations of mill ing and scouring very well, hence acid colours are generally un suitable for tweed yarns or for loose wool. They are largely employed, however, in dyeing other varieties of woollen yarn, silk yarn, union fabrics, dress materials, leather, etc. Previous to the discovery of the coal-tar colours very few acid colours were known, the most important one being indigo extract. Prussian blue as applied to wool may also be regarded as belonging to this class, also the purple natural dyestuff, orchil or cudbear. Xylidine scarlet, discovered in 1879, was the first synthetic colouring matter of this class, which comprises such members as picric acid, tartrazine, orange II, fast acid violet, lissamine fast yellow and orange, alphanol, cyanol, lanacyl, kiton and neolan colours. The last compounds contain copper and chromium and are therefore mordant colours which can be dyed direct on wool from an acid bath. They are fast to milling.

(3) Direct cotton colours may be regarded as a particular type of acid colours because wool and silk dye in the presence of acetic acid, but they are characterized by the fact that cotton shows a decided affinity for them. At the same time cotton does not show that complete absorption of colour which is characteristic of wool and merely absorbs a portion of the colour from the bath, in amount depending very much upon the concentration of the dye liquor. The first colouring matter of the class was the so-called congo red, discovered in 1884. Since that time a very great number have been introduced which yield almost every variety of colour. The method of dyeing cotton consists in merely boiling the material in a solution of the dyestuff, when the cotton absorbs and retains the colouring matter by reason of a special natural affinity. The concentration of the dyebath is of the greatest im portance, since the amount of colour taken up by the fibre is in an inverse ratio to the amount of dye liquor present in the bath. The addition of i to 3 oz. sodium sulphate and 2 to 3 oz. carbonate of soda per gallon gives deeper colours, since it dim inishes the solubility of the colouring matter in the water and increases the affinity of the cotton for the colouring matter. An excess of sodium sulphate is to be avoided, otherwise precipitation of the colouring matter and imperfect dyeing result. With many dyestuffs, it is preferable to use a to oz. soap instead of soda. On cotton the dyed colours are usually not very fast to light, and some are sensitive to alkali or to acid, but their most serious defect is that they are not fast to washing, the colour tending to run and stain neighbouring fibres. Wool and silk are dyed with the direct colours either neutral or with the addition of a little acetic acid to the dyebath. On these fibres the dyed colours are usually faster than on cotton to washing, milling and light ; some are fast even to light, e.g., diamine fast red, chrysophenine, hessian yellow, etc. Many of the direct colours are very useful for dyeing plain shades on union fabrics composed of wool and cotton, silk and cotton, or wool and silk. Owing to the facility of their application, they are also very suitable for use as household dyes, especially for cotton goods. Colours of this type are benzo purpurine, benzo fast violet, ch1orazo1 and dianol colours. The fastness may be improved by after treatment, (a) diazotizing and developing, (b) formaldehyde treatment and (c) of ter treat ment with metallic salts. (a) Applies to colours such as primuline which contain a free amido group and can be passed through a bath of sodium nitrite and hydrochloric acid and afterwards through a solution of an'amino compound or phenol. Primuline yellow is converted into a red by this treatment. In some cases the colour change is not so marked, but the colours are distinctly improved in fastness to washing. (b) The treatment with for maldehyde applies to the benzoform colours and it improves the fastness to washing. It is carried out at about 7o°C. with an aqueous solution. Treatment with boiling copper sulphate (o•5%) increases the light fastness.

Different batches of viscose silk show considerable variation in affinity for the direct cotton colours. In some cases colours appear distinctly light in shade on one batch and dark on another batch of viscose, so that defects may appear in manufactured articles which happen to contain the two types of viscose. Whit taker has shown that this trouble may be overcome by the careful selection of colours which show low capillarity, or in the case of shades composed of mixtures of colours by making these up from colours of nearly the same capillary properties. The icyl colours do not show conspicuous differences when dyed on different batches of viscose silk.

So many colours have been introduced for the direct dyeing of acetate silk that methods of treating the fibre in order to im part to it an affinity (which it does not show in the ordinary con dition) for direct cotton colours have comparatively little interest. The hydrolyzing, or saponifying, action of alkali, if cautiously applied to the silk, does not reduce its lustre but may result in loss of weight and strength. This treatment and the action of ammonium thiocyanate impart to acetate silk some affinity for direct cotton colours.

Immunized cotton, that is cotton first converted into alkali cellulose and then treated with toluol sulphonic chloride or allied compounds, shows no affinity for direct colours. The process of immunizing may be applied to yarn or piece goods either wholly or locally. Esterified cotton has somewhat similar properties.

Dyeing with Reduced Colour Solutions.

Many insoluble coloured substances form soluble reduction products which show a definite affinity for fibres. Characteristic in this respect are (I) sulphur colours which dissolve in sodium sulphide and (2) vat colours which react with sodium hydrosulphite and other reducing agents in a somewhat similar way. These colours are most easily applied to vegetable fibres because the solution is invariably alkaline and special devices have to be employed in the case of wool. As a rule it is generally found preferable to use direct dyeing acid and mordant colours for wool, but a number of prep arations have been put on the market to protect wool from the injurious action of alkali in dyeing sulphur and vat colours.(i) Sulphur colours. The material is heated for about one hour in a solution of the colour (io to 15%), with the addition of sodium carbonate (i to i o% ), common salt (i o to 2o%) and sodium sulphide (5 to 3o%) ; it is then washed in water and may be developed by heating in a bath containing 2 to 5% of bichro mate of soda, and 3 to 6% acetic acid. A final washing with water containing a little soda to remove acidity is advisable. The sulphide colours are remarkable for their fastness to light, alkalis, acids and washing, but unless proper care is exercised the cotton is apt to be tendered on being stored for some time. • This is particularly noticeable in the case of blacks and to some extent with yellow sulphur colours. The cause of tendering has been the subject of much research. Zanker (1914) considers it to be due to the oxidation of sulphur in chemical combination with the dyestuff. Most workers agree that the tendering is due to the formation of acid. Holden's method of overcoming the tender ing is probably the most efficient. It consists in impregnating the cotton with tannic acid, and then passing through lime water before dyeing in the sulphur colour. The tannate of lime so formed provides an insoluble and powerful base present on the fibre and combined only with the tannic acid. Sulphur colours are suitable for dyeing goods which are intended for rubber proofing.

Some kinds of finishing materials affect the fastness of sulphur colours very materially. Hannay (1912) has shown that castor oil preparations (soluble oil, monopol soap) very materially re duced the light-fastness of sulphur colours.

(2) Vat dyeing is one of the oldest dyeing processes, naturally occurring substances being used for the production of fermentation vats for the dyeing of indigo blue. In the early days of dyeing in England and as soon as dyers were by law permitted to use indigo in place of woad, vats were prepared from woad, bran, madder and wood ashes. These substances were used for wool dyeing long after chemical reagents had been suggested and intro duced for cotton dyeing. Practically any substance or mixture of substances capable of producing hydrogen in an alkaline medium will reduce indigo. The reduction product, leuco indigo or indigo white, dissolves in the alkali with a yellow colour. In the fer mentation vat, butyric acid fermentation is induced in the bran and madder by the ferment contained in woad and hydrogen is formed. Wood ashes or lime provide the alkali necessary for the solution of the indigo white. Other vats which have found appli cation in dyeing are the copperas and lime, zinc-lime, bisulphite zinc-lime, and the sodium hydrosulphite vats. The last is the most important; it produces a vat free from sediment and little loss of indigo. It is usual to prepare a stock vat and then to add some of this to a large volume of water (r,000 gals.) from which the dissolved oxygen has been removed by adding a little sodium hydrosulphite (91 ozs.) and caustic soda a pint 76°Tw.). The stock vat may be made suitable for cotton by mixing ioo lb. indigo (2o% paste) with To gals. warm water and 5 gals. caustic soda 76°Tw., heating to 4o-50°C. and adding about 20 lb. sodium hydrosulphite. Dyeing is carried out by dipping cotton in the cold vat for a few minutes, and darker shades are obtained by repeated dipping alternated with exposure to air. Washing with cold water assists the oxidation of the leuco compound. In dyeing wool, the amount of alkali in the vat must be strictly limited. Substances such as protectol or the sulphite pulp waste liquor from paper manufacture and glue are recommended for use in wool dyeing with vat colours to protect the fibre from the in jurious action of alkali. In wool dyeing a temperature not lower than 7o°C. is required for the dyeing of other vat colours and in all cases the time of dyeing for wool is longer than for cotton. Wool requires to 2 hours for the dyeing of indigo. It is now difficult to buy suiting dyed with indigo, for the shade is generally imitated with acid chrome colours and with other acid (wool) colours.

The leuco compounds of the anthraquinone colours are usually less soluble than those of the indigoid colours and require more caustic soda to produce a vat. The amount of alkali has fre quently to be double the quantity used for indigo, so they are difficult to apply to wool. Indanthrene blue is a colour of re markable fastness, but unfortunately this cannot be said of all members of the series of colours of which this is the type. Cibanone yellow fades on exposure to light and at the same time the fibre is considerably tendered. In connection with colours of this type it has been noticed by F. Scholefield that if light is allowed to fall on the fabric during the development of colour after dyeing in the vat, the shades appear brighter than if de veloped in the dark but the fabric becomes tender in a few minutes and other colours that may be dyed in the same vat are destroyed.

The production of a vat is always accompanied by chemical change, which is shown by the formation of solution and fre quently by colour change ; but this is not so in the case of in danthrene which merely forms a vat of different shade of blue to that of the decoction of colour and water. Indanthrene yellow produces a blue vat, thio-indigo red gives a yellow vat.

The indigosols and corresponding anthraquinone products (sole don colours) are vat colours presented to the dyer in an already reduced condition. They are applied like acid dyes to wool and silk and are mixed with a solution of sodium nitrite and padded on cotton. Various acid oxidizing agents may be used for de veloping the colours on wool and treatment with acid to react with the sodium nitrite in the case of cotton. They may be developed in other ways, one of the most interesting being that of steaming cotton padded with chlorate of soda, vanadium chlor ide, neutral ammonium oxalate and indigosol 0 which resembles a process of producing aniline black. This renders possible the production of different colours side by side and is most valuable from the point of view of calico printing. Colours include duran threne, algol, ciba, besides those already mentioned.

Mordanting and Dyeing.

(i) Basic colours applied to cot ton. Unlike the animal fibres cotton has little affinity for the basic colours. It is usual to deposit tannic acid on the fibre in the form of an insoluble tannate. For this purpose pieces are steeped in a solution containing 2 to 6 oz. per gallon tannic acid and after being evenly squeezed are passed through a warm solution of tartar emetic or other salt of antimony or tin. The tannic acid has the power of combining with the base of the colouring matter in the subsequent dyeing operation, which is generally carried out with 2 2 % colour on the weight of cotton to be dyed and suffi cient water, in the cold or if the temperature is raised at all it is best not higher than 7o°C. The basic colours are moderately fast to soap, but most of them are very loose to light. Methylene blue is one of the best in this respect. The first coal-tar colour mauve belonged to this dyeing class, which is especially remark able for brilliance and high colouring power. One natural colour which has long been known to dye in this way is the barberry, which contains the alkaloid berberine; but in 1918 Everest showed that the flower colours (antho-cyanines) could be dyed on tanned cotton. They are fast to light but loose to soap, and in respect to these properties are therefore quite different from the synthetic colours dyed in this way. In the dyeing of basic colours, tannic acid may be substituted by katanol (a phenolic compound containing sulphur) which can be applied in alkaline solution and in presence of salt. It does not require fixing but appears to have some affinity for cotton which is rather like that of direct colours. Direct cotton, sulphur and vat colours will act as mordants for basic colours forming lakes on the fibre.Some important basic colours are rhodamine, brilliant green, auramine and methyl violet. A dyestuff astrafloxine has been offered as a substitute for rhodamine.

(2) Mordanting with metallic compounds and dyeing. The deposition and fixation of metallic oxides or basic salts of certain metals on vegetable and animal fibres is a necessary feature of the production of colour in the case of certain organic compounds such as alizarine and haematine which may be termed colour principles. Colour principles are the essential constituents as far as dyeing is concerned of many woods and other natural products which have found considerable application, consequently mordant ing operations have been of great interest to dyers. The method provides some dyeings of great fastness. The animal fibres are very easily mordanted. For example, wool boiled for 1 to 12 hours with 2-3% potassium bichromate absorbs chromic acid and reduces it to chromium chromate tinting the fibre a pale olive yellow. On subsequent dyeing the chromium chromate is reduced to chromium hydrate by a portion of the dyestuff and this result can with advantage be obtained previous to dyeing by the use of assistants such as sulphuric acid, cream of tartar, tartaric acid, lactic acid, etc. For special purposes chromium fluoride, chrome alum, etc., are employed. Alum or aluminium sulphate (8%), along with acid potassium tartrate (cream of tartar) (7%), is used for brighter colours—e.g., reds, yellows, etc. The object of the tartar is to retard the mordanting process and ensure the penetration of the wool by the mordant, by preventing superficial precipitation through the action of ammonia liberated from the wool; it ensures the ultimate production of clear. bright, full colours. For still brighter colours, notably yellow and red, stan nous chloride was at one time largely employed, but it is used less frequently; and the same may be said of copper and ferrous sulphate, which were used for dark colours. Silk may be of ten mordanted in the same manner as wool, but as a rule it is treated like cotton. The silk is steeped for several hours in cold neutral or basic solutions of chromium chloride, alum, ferric sulphate, etc., then rinsed in water slightly, and passed into a cold dilute solution of silicate of soda, in order to fix the mordants on the fibre as insoluble silicates. Cotton does not, like wool and silk, possess the property of decomposing metallic salts, hence the methods of mordanting this fibre are more complex and vary according to the metallic salts and colouring matters employed, as well as the particular effects to be obtained. One method is to impregnate the cotton with a solution of so-called sulphated oil or turkey-red oil ; the oil-prepared material is then dried and passed into a cold solution of some metallic salt—e.g., aluminium acetate, basic chromium chloride, etc. The mordant is thus fixed on the fibre as a metallic oleate, and after a passing through water containing a little chalk or silicate of soda to remove acidity, and a final rinsing, the cotton is ready for dyeing. Another method of mordanting cotton is to fix the metallic salt on the fibre as a tannate instead of an oleate. This is effected by first steeping the cotton in a cold solution of tannic acid or in a cold decoction of some tannin matter, e.g., sumach, in which operation the cot ton attracts a considerable amount of tannic acid ; after squeezing, the material is steeped for an hour or more in a solution of the metallic salt, and finally washed. The mordants employed in this case are various—e.g., basic aluminium or ferric sulphate, basic chromium chloride, stannic chloride (cotton spirits), etc. There are other methods of mordanting cotton besides those mentioned, but the main object in all cases is to fix an insoluble metallic compound on the fibre. It is interesting to note that whether the metallic oxide is united with the substance of the fibre, as in the case of wool and silk, or precipitated as a tannate, oleate, silicate, etc., as in the case of cotton or silk, it still has the power of combining with the colouring matter in the dyebath to form the coloured lake or dye on the material.

The dyeing operation consists in working the mordanted mate rial in a decoction of the necessary colouring matter, the dyebath being gradually raised to the boiling point. With many colouring matters, e.g., with alizarin, it is necessary to add a small per centage of calcium acetate to the and also acetic acid if wool is being dyed. In wool-dyeing, also, the mordanting opera tion may follow that of dyeing instead of preceding it, in which case the boiling of the wool with dyestuff is termed "stuffing," and the subsequent developing of the colour by applying the mordant is termed "saddening," since this method in the past has usually been carried out with iron and copper mordants, which give dull or sad colours. The method of "stuffing and saddening" may, however, be carried out with other mordants, even for the pro duction of bright colours, and it is now frequently employed with certain alizarin dyestuffs for the production of pale shades which require to be very even and regular in colour. There is still another method of applying mordant colours in wool-dyeing, in which the dyestuff and the mordant are applied simultaneously from the beginning; it is called the single-bath method. This process has become of greater interest ; copper and chromium (chromium oxalate or "chromosul") being used in conjunction with acid azo colours. Some colouring matters which contain copper or chromium in combination are soluble in water and are applied like acid colours (Neolan colours).

Deposition of tannate of iron on and in the fibre is the method used for the dyeing of logwood on cotton. Logwood still finds use for the production of black both on cotton and wool. In the case of wool it is dyed on chrome mordant. Acetate silk may be dyed black (Bedford's patent) by treating first with logwood extract (haematine) and afterwards adding borax and nitrate of iron.

For dyeing turkey-red, cotton is boiled but not bleached. Af ter boiling, mordanting with red liquor (4° Tw.) and ageing, fixing with phosphate or silicate or arsenate of soda (0.5% solution) follows. Dyeing is carried out at the boil with Io% alizarine paste and the goods are afterwards soaped and cleared (using a little stannous chloride). Steaming improves the colour.

Interest in mordant dyeing on cotton is diminishing considerably with the introduction of colours which are more readily applied and can compete well with the fastest mordant colour alizarine or turkey-red in point of fastness.

Cutch is a natural colour which is still very largely used in dyeing. Sailors believe that this colour protects the fabric of fish ing nets from the action of light and air. It is dyed with copper sulphate in the bath but contains in addition to the mordant colour principle (catechin), a kind of tannic acid (catechu tannic acid), consequently this colour can be topped with basic colours.

Colours Produced on the

Aniline black is pro duced in situ•upon the fibre by the oxidation of aniline. It is chiefly used for cotton, also for silk and cotton (silk union) fabrics, but seldom or not at all for wool. Properly applied, this colour is one of the most permanent to light and other influences with which we are acquainted. One method of dyeing cotton is to work the material for about two hours in a cold solution con taining aniline (10 parts), hydrochloric acid (2o parts), bichro mate of potash (2o parts), sulphuric acid (2o parts), and ferrous sulphate (r o parts) . The ferrous sulphate here employed is oxi dized by the chromic acid to a ferric salt, which serves as a carrier of oxygen to the aniline. This method of dyeing is easily carried out, and it gives a good black ; but since much of the colouring matter is precipitated on the fibre superficially as well as in the bath itself, the colour has the defect of rubbing off. Another method is to impregnate the cotton with a solution containing aniline hydrochloride (35 parts), neutralized with addition of a little aniline oil, copper sulphate (1.6 part), sodium chlorate (r o parts), ammonium chloride (r part). Another mixture is 1.8 part aniline salt, 12 parts potassium ferrocyanide, 200 parts water, parts of potassium chlorate dissolved in water. After squeez ing, the material is passed through a special oxidation chamber, the air of which is heated to about 5o°C. and also supplied with moisture. This oxidizing or ageing is continuous, the material pass ing into the chamber at one end in a colourless condition, after about 20 minutes passing out again with the black fully de veloped. A final treatment with hot potassium bichromate and soaping is necessary to complete the process. In this method probably chlorate of copper is formed and this being a very unstable compound, readily decomposes and the aniline is oxi dized by the liberated chlor-oxygen compounds. The presence in the mixture of a metallic salt is very important in aiding the development of the black (Lightfoot's observation) . Salts of vanadium and cerium may be substituted for copper. In the of ter chroming process, chromium is fixed on the fibre and in all methods some mineral substance is fixed ; chromium in the dyed black and iron in the prussiate black. The organic compound on the fibre is produced by oxidation which proceeds in four stages to nigraniline and the condensation of this substance with aniline. At the end of the ageing process there should be some unchanged aniline to condense and produce an ungreenable black in the chroming process. On the fibre, chromate of nigraniline may be formed. There is still much material for further investi gation especially concerning the prussiate black. One of the serious disadvantages of aniline black is the liability to tender the cotton. It is by no means certain whether this is due to oxidation of the cellulose or to the action of acid upon it during ageing. The latter is probable, for substances which prevent drying during ageing also prevent tendering.(2) The insoluble azo colours are produced as insoluble col oured precipitates by adding a solution of a diazo compound to an alkaline solution of a phenol, or to an acid solution of an amido compound. The necessary diazo compound is prepared by allowing a solution containing nitrous acid to act upon a solution of a primary aromatic amine. It is usually desirable to keep the solutions cool with ice, owing to the unstable nature of the diazo compounds produced. (Products can be obtained which are stable and only decompose on acidifying.) The colour obtained varies according to the particular diazo compound, as well as the amine or phenol employed, f3-naphthol being the most useful among the latter. The same coloured precipitates are produced upon the cotton fibre if the material is first impregnated with an alkaline solution of the phenol, then dried and passed into a cold solution of the diazo compound. The most important of these colours is para-nitraniline red, which is dyed in enormous quantities on cotton pieces. The pieces are first prepared by running them on a padding machine through a solution made up of 3o grms. j3-naphthol, 20 grms. caustic soda, 5o grms. turkey-red oil, and 5 grms. tartar emetic in r,000 grms. (1 litre) water. They are then dried on the drying machine, and are passed, after being allowed to cool, into the diazo solution, which is prepared as follows : 15 grms. para-nitraniline are dissolved in 53 c.c. hydro chloric acid (34°Tw.) and a sufficiency of water. To the cold mixture a solution of roe grms. sodium nitrite is added while stirring. The whole is then made up to 1,200 c.c. and just before use 6o grms. sodium acetate are added. The colour is developed almost immediately, but it is well to allow the cotton to remain in contact with the solution for a few minutes. The dyed cotton is squeezed, washed, soaped slightly, and finally rinsed in water and dried. A brilliant red is then obtained which is fast to soap but not to light. If the para-nitraniline used in the foregoing process is replaced by meta-nitraniline, a yellowish-orange colour is obtained; with a naphthylamine, a claret red; with amido-azo toluene, a brownish red ; with benzidine, a dark chocolate ; with dianisidine, a dark blue; and so on. The dyed colours are fast to washing and are much used in practice, particularly the para nitraniline red, which has served as a substitute for turkey-red, although it is not so fast to light as the latter. Superior results can be obtained by substituting Naphthol A.S. (the anilide of -oxynaphthoic acid) and other related products for f3-naphthol. The combinations of these compounds with various diazotized amines result in shades which sometimes differ from those with 0 -naphthol, generally giving improved appearance and almost always colours of superior fastness. Some will stand the full bleaching process. A further advantage is that the cotton shows decided direct affinity for Naphthol A.S. products and there is no necessity to dry the material after padding. E. Higgins (1927) has given valuable information regarding the behaviour of in soluble azo colours.

(3) Mineral colours. These include chrome yellow, iron buff, prussian blue, manganese brown and khaki.

Chrome yellow is only useful in cotton dyeing as a self-colour, or for conversion into chrome orange, or, formerly in conjunction with indigo, for the production of fast green colours. The cotton is first impregnated with a solution of lead acetate or nitrate, squeezed, and then passed through a solution of sodium sulphate or lime water to fix the lead on the fibre as sulphate or oxide of lead. The material is then passed through a solution of bichromate of potash. The colour is changed to a rich orange by a short, rapid passage through boiling milk of lime, and at once washing with water, a basic chromate of lead being thus produced. The colour is fast to light, but has the defect of being blackened by sulphuretted hydrogen.

Iron buff is produced by impregnating the cotton with a solu tion of ferrous sulphate, squeezing, passing into sodium hydrate or carbonate solution, and finally exposing to air, or passing through a dilute solution of bleaching powder. The colour ob tained, which is virtually oxide of iron, or iron-rust, is fast to light and washing.

Prussian blue is applicable to wool, cotton and silk, but since the introduction of coal-tar blues its employment has been very much restricted. The colour is obtained on cotton by first dyeing an iron buff, according to the method just described, and then passing the dyed cotton into an acidified solution of potassium ferrocyanide, when the blue is at once developed. A similar method is employed for silk. Wool is dyed by heating it in a solution containing potassium ferricyanide and sulphuric acid. The colour is developed gradually as the temperature rises ; it may be rendered brighter by the addition of stannous chloride. On wool and silk prussian blue is very fast to light, but alkalis turn it brown (ferric oxide).

Manganese brown or bronze can be applied in wool, silk and cotton dyeing. The animal fibres are readily dyed by boiling with a solution of potassium permanganate, which, being at first absorbed by the fibre, is readily reduced to insoluble brown man ganic hydrate. Since caustic potash is generated from the per manganate and is liable to act detrimentally on the fibre, it is advisable to add some magnesium sulphate to the permanganate bath in order to counteract this effect. Imitation furs are dyed in this manner on wool-plush, the tips or other parts of the fibres being bleached by the application of sulphurous acid. Cotton is dyed by first impregnating it with a solution of manganous chloride, then dyeing and passing into a hot solution of caustic soda. There is thus precipitated on the fibre manganous hydrate, which by a short passage into a cold dilute solution of bleaching powder is oxidized and converted into the brown manganic hy drate. This manganese bronze or brown colour is very susceptible to, and readily bleached by, reducing agents; hence when exposed to the action of an atmosphere in which gas is freely burnt, the colour is liable to be discharged, especially where the fabric is most exposed. In other respects manganese bronze is a very fast colour.

Khaki is a mixture of iron buff and chromium oxide. The green shades of khaki are as a rule most sought after and on this account it is necessary to secure the deposition of much chromium on the fibre. This may be done by tanning and then destroying the tannic acid with sodium bichromate ; otherwise this would destroy the cotton.

Dyeing on a Large Scale.

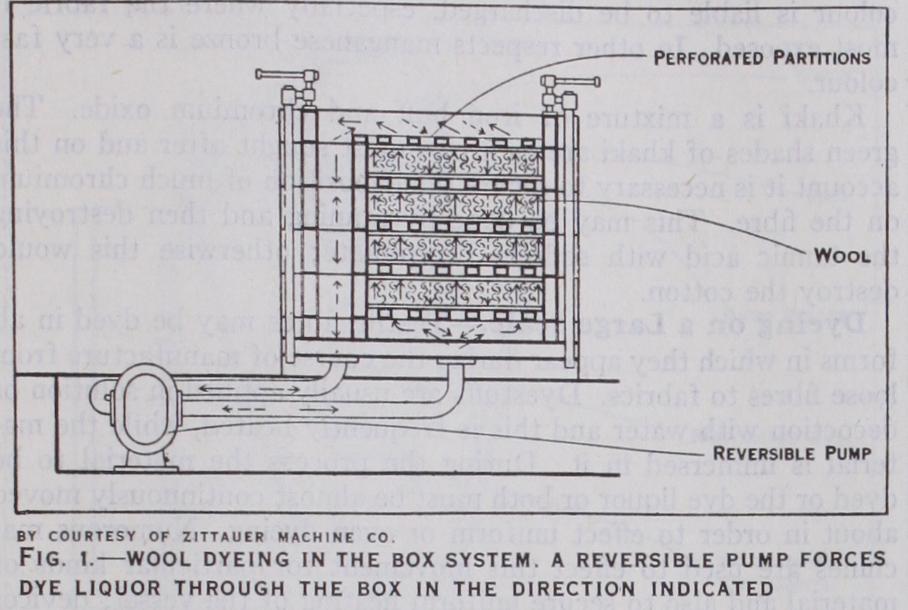

Textile fibres may be dyed in all forms in which they appear during the course of manufacture from loose fibres to fabrics. Dyestuffs are usually applied in solution or decoction with water and this is frequently heated, while the ma terial is immersed in it. During the process the material to be dyed or the dye liquor or both must be almost continuously moved about in order to effect uniform or even dyeing. Numerous ma chines are used to effect this movement for particular kinds of material and also to secure uniform heating of the vessel; devices are fitted for preventing the material from coming into contact with the steam pipes. Loose material is liable to become matted together so machines have been arranged with hooks or fingers to prevent this. It is best dealt with by circulating the liquor through the material (fig. 1). Loose dyed wool is especially useful in pro ducing fancy fabrics with fibres dyed in different colours.

Yarn Dyeing.

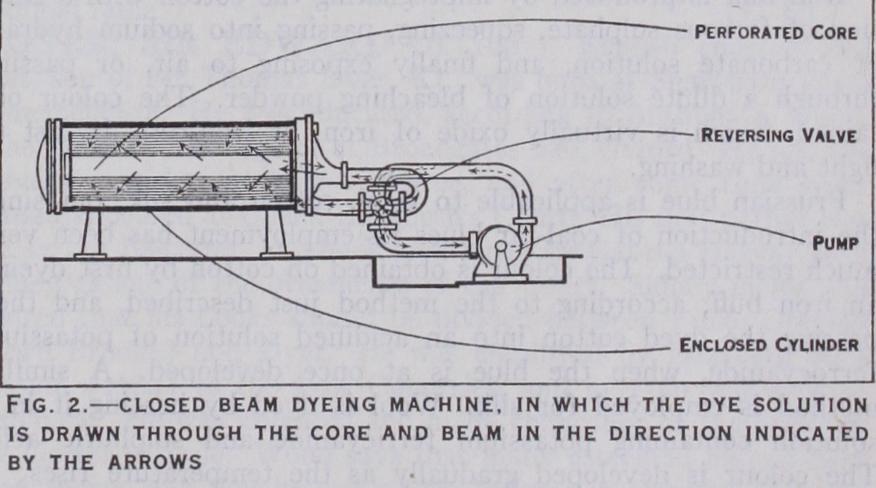

Yarn is dyed in the form of hanks, warps, cops and cheeses. The hank form involves the most simple devices for obtaining even results by turning the material. Machines made to imitate the effect of turning the yarn by hand over wooden pegs, take the form of a series of reels each holding about 2 lb. of yarn which are arranged so that large batches can be lifted in and out of the liquid automatically. In other machines the yarn is arranged on rods or carriers which revolve on a central axis into half cylin drical dye vats and, during the revolution, the rods are turned so that the yarn moves to another position. Machines have been in troduced for dyeing warps on the beam, the dye liquor being caused to circulate through the material, and the system meets with considerable success.

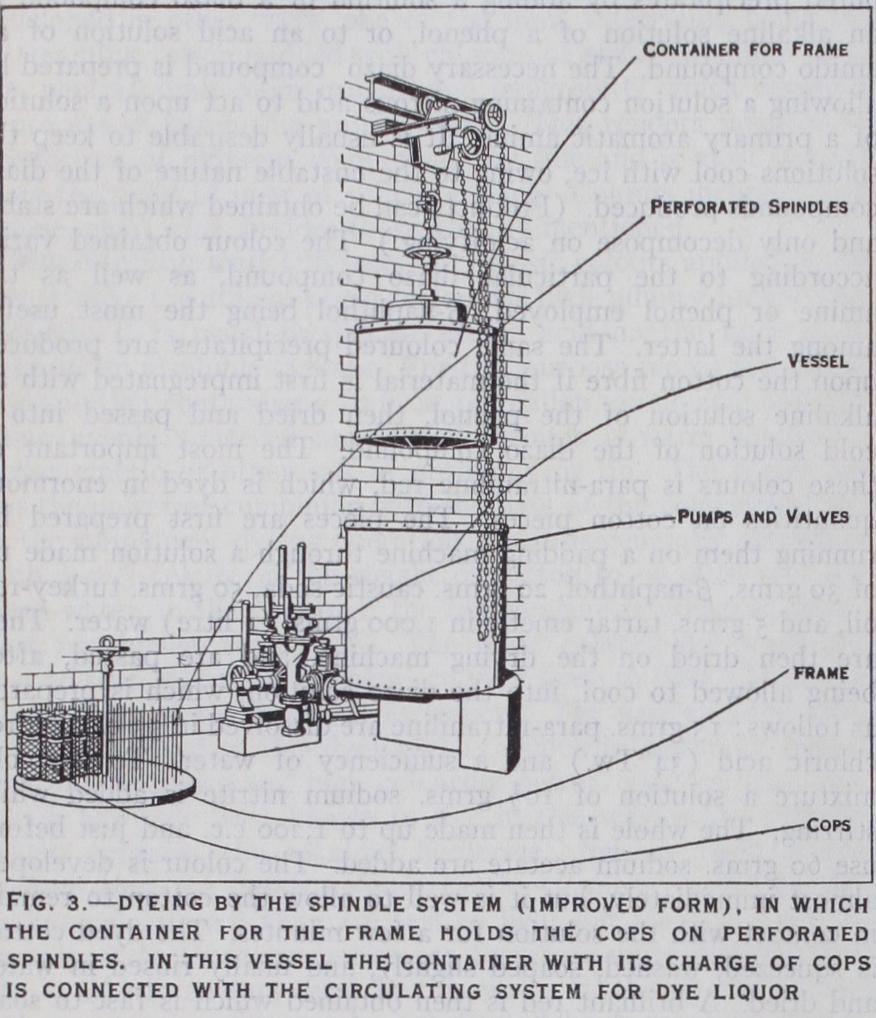

Large quantities of yarn, especially cotton, are dyed in the cop, for weft. The main advantage of this method is at once apparent, inasmuch as the labour, time and waste of material incurred by reeling into hanks and then winding back into compact form, so as to fit into the shuttle are avoided. A thin tapering perforated metallic tube is inserted in the hollow of each cop. The cops are then attached to a perforated disc (which constitutes the lid of a chamber or box) by inserting the protruding ends of the tubes into the perforations. The chamber is now immersed in the dye-bath and the hot liquor is drawn through the cops by means of a cen trifugal pump and returned continuously to the dye-bath. This principle is known as the skewer or spindle system.

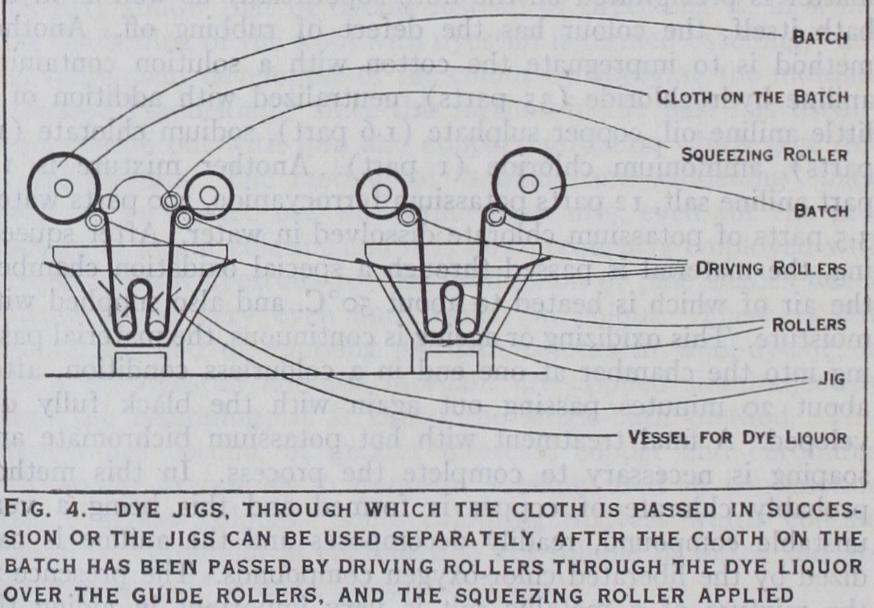

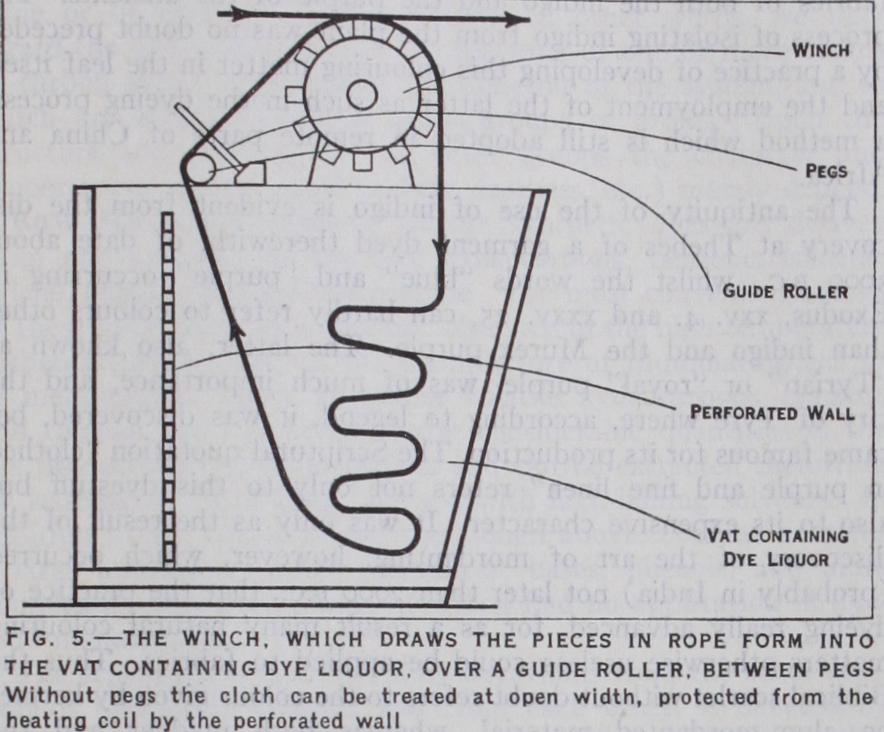

In the so-called "compact" system of cop dyeing the cops are packed as closely as possible in a box, the top and bottom (or the two opposite sides) of which are perforated, the interstices be tween the cops being filled up with loose cotton, ground cork or sand. The dye liquor is then drawn by suction or forced by pres sure through the box, thus permeating and dyeing the cops. Dyeing of Pieces.—Plain shades are usually dyed in the piece, this being the most economical and at the same time the most expeditious means of obtaining the desired effect. In the dye-jigger (fig. 4) the goods are passed backwards and forwards over guide rollers between two batching rollers. The arrangement admits of treating a large quantity of material with comparatively little dye liquor. Another machine is that shown in fig. 5. This is suitable for heavy fabrics. The pieces are stitched end to end in a band which passes over a winch. Washing off may be done on the same machine.

Except for the dyeing of light shades only the preliminary oper ations of bleaching (washing and scouring) are carried out before dyeing.

Theory of Dyeing.

The peculiar property characteristic of dyestuff s, as distinguished from mere colouring matters, namely, that of being readily attracted by the textile fibres, notably the animal fibres, appears to be due to their more or less marked acid or basic character. Intimately connected with this is the fact that these fibres also exhibit partly basic and partly acid characters due to the presence of carboxyl and amido groups. The behaviour of magenta is typical of the basic colours. Rosaniline, the base of magenta, is colourless, and only becomes coloured by its union with an acid, and yet wool and silk can be as readily dyed with the colourless rosaniline (base) as with the magenta (salt). The ex planation is that the base rosaniline has united with the fibre, which here plays the part of an acid, to form a coloured salt. It has also been proved that in dyeing the animal fibres with magenta (rosaniline hydrochloride), the fibre unites with rosaniline only, and liberates the hydrochloric acid. Further, magenta will not dye cotton unless the fibre is previously prepared, e.g., with the mor dant tannic acid, with which the base rosaniline unites to form an insoluble salt. In dyeing wool it is the fibre itself which acts as the mordant. In the case of the acid colours the explanation is similar. In many of these the free colour-acid has quite a differ ent colour from that of the alkali-salt, and yet, on dyeing wool or silk with the free colour-acid, the fibre exhibits the colour of the alkali-salt and not of the colour-acid. In this case the fibre evi dently plays the part of a base. Another fact in favour of the view that the union between fibre and colouring matter is of a chemical nature is that by altering the chemical constitution of the fibre its dyeing properties are also altered; oxycellulose, nitrocellulose and acetate silk for example, have a greater attraction for basic colours than cellulose. Such facts and considerations as these have helped to establish the view that in the case of dyeing animal fibres with many colouring matters the operation is a chemical process, and not merely a mechanical absorption of the dyestuff. A similar explanation does not suffice, however, in the case of dyeing cotton with the direct colours. These are attracted by cotton from their solutions as alkali salts, apparently without decomposition, the affinity existing between the fibre and colouring matter is distinctly feeble in comparison with wool. This fibre is capable of taking up as much as 20% of acid colour without appearing bronzey. Cotton absorbs under favourable conditions about 2% of actual direct colour.The dyeing of cotton is most probably of a physical character but there are different opinions as to the nature of this. Some fa vour colloidal, some purely mechanical (solid solution) and some electrical theories. The latter explains phenomena which occur during dyeing and in some instances supports the chemical as well as the mechanical theory. In the case of colours which are dyed on mordants the question is merely transferred to the nature of the attraction which exists between the fibre and the mordant. G. T. Morgan finds that the co-ordination theory of valency ex plains and correlates known facts with regard to mordant dyeing.

The trend of advance in the industry in America, in Great Britain and on the Continent is shown by a real endeavour to meet the demands for fast dyeings and a greater value and utiliza tion of scientific methods in the investigation of processes and the effects produced by them. Colour measuring and matching instruments have been greatly improved and may prove of value in giving a more definite expression to fastness. Products pro duced by the action of light on vat colours have been isolated, the first of these being the oxidation product, isatin, from indigo dyed cotton (1927). In Great Britain the Society of Dyers and Colourists has appointed a committee with F. Scholefield as chairman to consider the whole question of fastness and already contributions have been made towards elucidating some of the problems. Many of these can only be solved by steady co-opera tion of workers. In December 1925 the dyeing industry suffered a severe loss by the death of Edmund Knecht, who had enriched tinctorial and analytical chemistry by important researches, many of which are recorded in the pages of the Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists. "A Manual of Dyeing" by E. Knecht, C. Rawson and R. Loewenthal is a work of reference of inter national fame. (E. HI.)