Earthenware

EARTHENWARE, a term generally associated with a coarser type of domestic pottery, although such cups and saucers and other table ware of thin pottery, are often called china (q.v.) in error. Earthenware can be made almost as thin as china, but it lacks translucency ; it is opaque. Its chief feature is that it will absorb moisture under the glaze, whereas china will not. A test adopted by the British customs officials is the application of red ink to the ware at a point where the glaze has been removed. If the ink is absorbed then it is classed as earthenware.

Earthenware embraces a wide range of pottery known under a variety of names, which usually indicate the place where the ware was first introduced. William Burton, a well-known author ity (see CERAMICS) , writes : "The word earthenware in its widest sense might be used to cover all varieties of pottery, as they are all made from some form of earthen or mineral substance taken out of the ground. In this broad sense a brick, a drainpipe and a Chinese vase might be equally described as earthenware, but though the chemical differences between them are slighter than would be supposed, they are so far apart in technique and final result that the names earthenware, stoneware and porcelain are very conveniently used to differentiate between them. In this restricted sense, the title `earthenware' covers all articles made from a single natural clay, or from mixtures of clay and other mineral substances which, wizen sufficiently fired for practical use, still remain porous, and need, therefore, if they are to be used for culinary, domestic, or decorative purposes, to be completed by the addition of an outer skin of glaze or glass melted on them. . . " A handbook compiled by British experts in conjunction with the educational committee of the Pottery and Glass Trades' Benevo lent Institution, gives the following definition of earthenware : "All ware may be termed earthenware which is porous in the material itself, and requires to be glazed before it can be applied to domestic use. Earthenware is opaque; it will not transmit light." The porosity of the "body" (the pottery itself without a glaze) may give a wrong impression to those who are not familiar with the ceramic industry. For instance, Bourry, a noted authority on the industry, points out that terra-cotta and stoneware are quite distinct in their properties. One of the chief characteristics of stoneware is its impermeability, whereas terra-cotta has a porous body. If the distribution of the temperature of the kiln is irregu lar, some of the ware, says Bourry, will be impervious and rightly termed "stoneware," whilst other ware, in the same kiln, will have a porosity between that of terra-cotta and stoneware. Judged on the basis of porosity, an article, Bourry points out, might be de fined as "stoneware" if viewed from one side and as "terra-cotta" if viewed from another ! Therefore it will be seen that earthenware and other types are not easily defined ; but for general purposes the term "earthenware" may be applied to pottery which is ab sorbent under the glaze.

Types of Earthenware.

Earthenware can, however, appear under several names, each chosen to distinguish a special type of ware. These are sometimes distinguished in the trade as agate ware, onyx ware, marbled ware, porphyry ware, that is, earthen ware made to imitate these various natural stones by mixing different coloured clays and glazing with a rich soft glaze.Delft ware is a general term applied to earthenware covered by an opaque tin enamel. It takes its name from Delft in Holland, where it was already largely made about 1600. Afterwards it was imitated at Lambeth, Bristol and Liverpool (England).

Faience ware is an earthenware with a soft rich glaze, generally decorated under the glaze ; named after the place of its origin, "Fayence." Majolica ware is the name given to an earthenware which is glazed with soft-coloured glazes. It takes its name from "Majorca." Queensware is a yellow or cream-coloured English earthenware first made about 175o by Josiah Wedgwood of Etruria (England). Many imitations of it have been made, which vary much in char acter, colour, hardness and quality.

Semi-porcelain and ironstone china are only trade names given to a harder form of earthenware. They are not in reality either porcelain or china.

The above descriptions cover in the main table ware and deco rative pottery; but earthenware is also used for more prosaic purposes, such as sanitary utensils, and containers for food and drink. Earthenware is also produced in almost every civilized country of the world, but the quality varies considerably. In this respect Great Britain has an enviable reputation for its earthen ware, just as it has for china.

Not only will the ware itself differ in its quality, according to the country of origin, but the decorations also are in most cases char acteristic of the nation that produces the earthenware, unless it is made specially for export. For instance, an eastern country like Japan expresses its artistic character in its pottery decora tions, but to capture the trade in western countries forsakes its national decorative schemes and adopts those common in the Western Hemisphere.

The principal raw materials used in the manufacture of earthen ware are : china clay, ball clay, flint and china stone.

China-Clay.

This mineral is found in many parts of the world, but the English mines at Cornwall and Devon are con sidered to produce the best clay for china-making. The clay is, of course, consumed largely by the British potters, but large quantities are exported, particularly to the United States, which have not a clay of the English quality, although quite good clays are found in Georgia.The British trade returns do not show the exports of china clay separately, but group them with china-stone. Of these two minerals 651,990 tons were sent abroad during 1926, more than half the quantity (361,797 tons) going to the United States. Belgium follows with 64,891 tons, and the Netherlands ranks third with 40,421 tons.

According to the last census of production, published in a series of preliminary reports during 1926, the output of British china clay was 8o5,000 tons, valued at £ 1,448,000. The previous census taken in 1907 gave the production of china-clay and china-stone together, the total being 726,000 tons, valued at £542,000.

Perhaps the next most important deposits of china-clay are to be found in Czechoslovakia, where an output of 40,000 tons per year is obtained. The best clay in Czechoslovakia is mined at Sedlice and Karlovy Vary. Czechoslovak clay is also exported to the extent of about 20,000 tons per year, a large part of this being sent to Germany.

China-clay is said to have resulted from the decomposition of granite through many centuries. Its main constituents are silica and alumina, and may be described generally as a white, amor phous powder. The clay is not usually mined in the ordinary way, but is washed down from the sides of the mine by huge jets of water thrown out of hosepipes at a high pressure. The water brings down the fine clay to the bottom of the mine, where any sand is allowed to settle out. The watery mixture of clay is then pumped up to the ground level, and run through a series of troughs, known as "micas," where it undergoes a process of levi gation, which consists of running the mixture into a trough from which the clay and water overflow into another trough, and so on throughout the series. While the mixture is passing through the "micas," the heavier materials—the impurities such as mica —gradually settle out and are left behind. On emerging from the "micas" the clay, now pure, is run into settling pits. From here it will pass to storage tanks and then to drying kilns. Finally it travels, in the form of lumps, to the storage room or "linhay," from which it will be loaded into railway trucks or conveyed to ships. It is the china-clay that gives plasticity to the mixture of materials used by the potter.

Ball Clay.

This is found principally in Devon and in Dor setshire, and is sometimes known as blue clay, owing to its grey ish-blue colour, which is due to organic matter. When fired at a moderate temperature it becomes white and remains absorbent; but some clays, if subjected to intense heat, are, according to Sandeman, rendered so hard that they are not easily scratched with a knife. Under such conditions these clays turn a yellowish colour and become non-absorbent.The clays vary, and the producer grades his clays into several qualities. Deposits will in some instances be found quite near the surface, while in other cases shafts will be sunk and the clay mined in branching "lanes," which vary in height according to the thickness of the vein of clay. It is necessary to "weather" the clay before sending it to the potter. To do this it is piled in heaps and exposed to the weather, and to the sun, rain and frost, probably for years, the whole being turned over at least once, so that all the clay may benefit from the exposure. This weather ing is said to increase the plasticity of the clay, an important matter to the potter.

The production of ball clay in the United Kingdom according to the census published in 1926 was 146,00o tons, which had a selling value of £128,000. The United States bought 17,87o tons in 1926, more than half the quantity exported that year, Italy and Belgium following with 4,669 and 2,167 tons respectively.

Flint.

Almost everyone is familiar with the pebbles or pieces of flint which are washed smooth by the waves on the sea-shore. These find their way into the body of earthenware. Not all flints are equally suitable ; the best are found in France, although there are many other sources of supply. To reduce the flints to a powdery mass so that they can be incorporated into the clay, the pebbles are heated (or calcined), a process which not only turns them white, but makes them more amenable to grinding. They are first of all crushed and then ground into very small particles in water, so that a white, or greyish, thin liquid paste is produced.The flint can withstand very high temperatures and therefore makes what might be termed a framework for the clay and other materials in the earthenware. The census of production for the United Kingdom published in 1926 gives a total of 188,000 tons for flints (including crushed and broken flints).

China-Stone.

This is an important ingredient in pottery, and there are deposits of a high quality in Cornwall, England, where the stone is mined by inserting explosive charges in holes drilled by compressed air boring machines. The stone has four recognized qualities or grades: hard purple (a white, hard rock with a purple tinge) ; mild purple (similar but softer) ; dry white or soft (a soft white rock) ; buff (similar to dry white, but with a slight yellow tinge).Silica is the principal constituent, amounting to about 74% in the dry white and over 8o% in the three other varieties. Oxide of alumina is the next important ingredient, amounting to about 18% in the dry white and from 7 to io% in the other varieties. The British output, according to the preliminary census reports published in 1926, was 51,000 tons, valued at £82,000. China stone gives the china "body" its translucency.

Manufacture of Earthenware.

Earthenware may be "thrown" on the potter's wheel or made under semi-mechanical conditions. In the case of the potter's wheel the prepared ball or lump of clay, revolving at the will of the potter on a small cir cular platform, is moulded by hand into whatever shape is aimed at. But for commercial production on a large scale, the thrower may form the ware in a mould, which shapes the exterior, the clay being pressed inside until the desired thickness is attained; or the clay and other materials may be introduced in the form of "slip" (a mixture of the materials with water) into a plaster of parts mould.A further method is that of "jolleying." In this process a mould forms one side of the article. If "flat" ware, such as saucers, plates, etc., is being made, the mould shapes the top or inside, and the under-side of the ware, which is on top in this process, is fashioned by cutting away the clay, as it revolves, by means of a tool which is cut to represent the profile of article to be made. The lathe also plays a part in finishing raw, or "green," clay articles. These processes are described and illustrated under CHINAWARE (q.v.).

Unlike china, earthenware, has little beauty of its own; also, as already stated, it is necessary to cover it with a hard glaze before it can be used for domestic or most ornamental purposes. Its decoration may be applied by painting or printing designs under or over the glaze ; or the decoration may consist of coloured glaze, in one colour or a variety of shades. A glaze is really a glass, and this may be coloured with various metallic oxides. The oxides produce different colours according to the temperature of the kiln and the method of heating. A variety of colour schemes is possible, but it is a speculative method of decoration for it is difficult accurately to predict what the colours will be when they emerge from the kiln. This element of chance is made use of by some potters, for it truthfully can be said that no two pots decorated in such a manner will be identical.

To perfect the decoration of pottery by the fusing of metallic oxides and a flux on the ware the potter needs to have a scientific knowledge ; that is, he must understand the chemical and physical properties of the metallic compounds, so that he may judge what their behaviour will probably be when subjected to heat in the kiln. With such knowledge some beautiful effects may be pro duced ; but many glorious combinations of coloured glazes have been the result not of predetermined efforts, but of unforeseen happenings in the kiln.

When the "green" or raw clay article has been made, it is fired or heated in an "oven." The glaze is then applied and the ware is fired again.

These processes are illustrated under CHINAWARE. Statistics.—The quantity of general earthenware, semi-porce lain and majolica produced in the United Kingdom, according to the census published in 1926, was 997,000 cwt., with a selling value of f2,691,000. These figures include only the returns in which weight was stated ; other returns gave selling value only, and the total in this case was £3,288,000, making a selling value of £5,979,000 for the year. Sanitary earthenware had a selling value of £1,252,000. Returns regarding the weight of the ware produced were only partially made and gave a total of 360,000 cwt., with a selling value of £854,000. Imports of general earthen ware (except high-grade earthenware resembling china), semi porcelain and majolica into the United Kingdom during 1926 amounted to 291,232 cwt., the largest consignments coming from Germany (195,158 cwt.), Czechoslovakia ranking second with 53,744 cwt. and France, third, with 15,748 cwt. Exports for the same year amounted to 716,724 cwt., as compared with cwt. in 1925. The United States is by far the best customer for British earthenware and china ; for although earthenware is pro duced in America, English pottery is eagerly bought. Canada is not far behind the United States, the next most important market being Australia, while other countries in the British empire and South America take substantial proportions of the output of the British factories.

Czechoslovakia produces large quantities of pottery for export. China has been dealt with under CHINAWARE. Italy is well known earthenware generally, Italy's imports are greater than her exports. Like other countries, France imports pottery as well as sending its own products overseas. Of faience and majolica the exports of French manufacture are considerable.

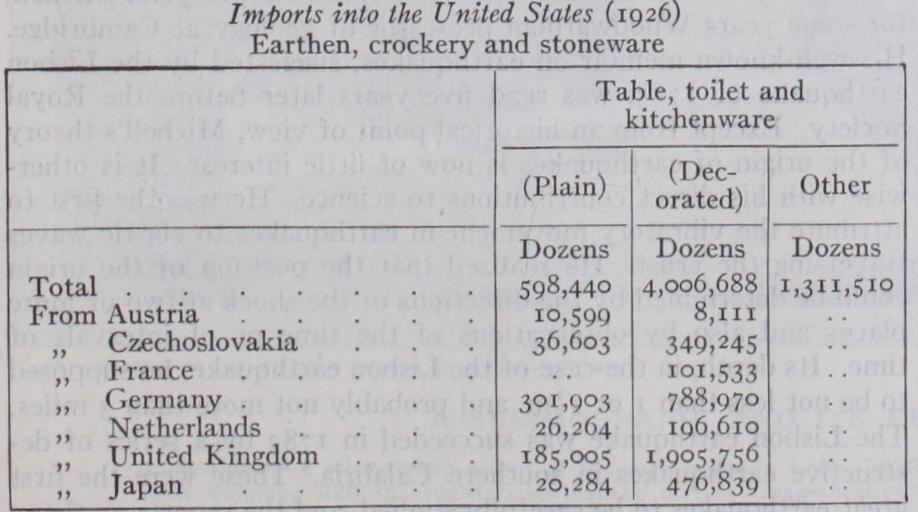

Classifications of pottery vary in almost every country. In the United States stoneware is grouped with earthenware and we get the record of imports in the table above.

The above countries are the principal sources of American import supply : smaller centres of production make up the grand totals.

See also CHINAWARE.

Bibliography.-W.

Burton, History and Description of English Earthenware and Stoneware (1904) : this book covers the history of the earthenware and stoneware made in England ; M. L. Solon, History and Description of Italian Majolica (190 7) ; A. Hayden, Chats on English Earthenware (1909), a collector's handbook; E. A. Sandeman, Manufacture of Earthenware (1917) ; A. Malinovszky, Ceramics (1922) , a book for chemists and engineers in the industry ; C. F. Binns, The Potter's Craft (1922), for the studio potter, schools, etc., Manual of Practical Potting (edit. C. F. Binns, 1922), gives numerous recipes for a great variety of bodies, glazes and colours; Text Book for Salespeople Engaged in the Retail Section of the Pottery and Glass Trades (1923), written by an expert committee in conjunction with the education committee of the Pottery and Glass Trades' Benevolent Institution for the guidance of students; R. Hain bach, Pottery Decorating (trans. C. Salter, 1924) ; E. Bourry, Treatise on Ceramic Industries (1926) ; C. J. Noke and H. J. Plant, Pottery (2nd ed., 1927), a popular account of the processes. (G. C.)