Earthquake

EARTHQUAKE. Though, from very early times, the chief phenomena of earthquakes have been well-known, it was not until the middle of the 19th century that the science dealing with them received a name. In 1858, the term Seismology was introduced by Robert Mallet. "The observation of the facts of earthquakes and the establishment of their theory," he says, "constitute Seismology (from qetoµos, an earthquake, a movement like the shaking of a sieve) ." History.—Over the conceptions of the ancient writers, we need not linger. Earthquakes find a place in many of their works, and especially in those of Aristotle, Seneca and Pliny. It was, indeed, natural that they should be interested in them, for in no other European countries are earthquakes so frequent or so violent as in Italy and Greece. On the facts as described by them, most writers relied until the middle of the i8th century, and it was only when they had freed themselves from their authority and trusted to their more complete knowledge of (then) recent earthquakes, that seismology can be said to have existed as a science. For this re lease, we are indebted, more than to anyone else, to John Michell, for some years Woodwardian professor of geology at Cambridge. His well-known memoir on earthquakes, suggested by the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, was read five years later before the Royal Society. Except from an historical point of view, Michell's theory of the origin of earthquakes is now of little interest. It is other wise with his direct contributions to science. He was the first to attribute the vibratory movement in earthquakes to elastic waves traversing the crust. He realized that the position of the origin could be determined by the directions of the shock at two or more places and also by observations of the time or of intervals of time. Its depth, in the case of the Lisbon earthquake, he supposed to be not less than 1 or I Zm. and probably not more than 3 miles. The Lisbon earthquake was succeeded in 1783 by a series of de structive earthquakes in southern Calabria. These were the first great earthquakes to be carefully studied, and the reports on them, by G. Vivenzio and by the committee appointed by the Neapolitan Academy are the earliest of a long series of important earthquake monographs. A succession of great earthquakes drew attention to many points of interest, and to none more significant than the changes of level that occurred during the New Madrid earthquake of 1811, the Kutch earthquake of 1819, and the Chilian earth quakes of 1822 and 1835.

In the first half of the 19th century, our knowledge of earth quakes received many additions. K. E. A. von Hoff, for instance, compiled a catalogue of earthquakes for the whole world. He also issued annual lists of earthquakes from 1821 to 1832. Von Hoff and others thus prepared the way for the general interest shown in the subject about the middle of the century. With this revival, the names of Alexis Perrey in France and Robert Mallet in Eng land are chiefly associated. Perrey's work lay mainly in three di rections. He published annual lists of earthquakes from 1843 to 1871, as well as a valuable series of regional memoirs, in which the greater part of the world was covered; but the subject to which he always turned with unfailing interest was the periodicity of earthquakes. He is now, perhaps, best known by the three laws in which he asserted that earthquakes are most numerous about the times of new and full moon, when the moon is nearest the earth, and when it crosses the meridian of the place of observa tion. The laws have been much criticized. It is possible that the third has no foundation ; the others have not yet been definitely proved or disproved.

The impress left by Robert Mallet on the science has been much more lasting. In his first memoir (1846), he applied the laws of wave-motion in solids to the explanation of earthquake-phe nomena and treated the subject "in a more determinate manner and in more detail than any preceding writer." He followed it up by his four reports to the British Association (1850-58). The third consists of his great catalogue of 6,831 earthquakes. In the fourth, he discussed this catalogue and published his valuable seismic map of the world. Mallet's last and most important work was his investigation of the Neapolitan earthquake of 1857, in which he applied several new methods of investigation. He deter mined the position of the epicentre and found the mean depth of the focus to be about 62 miles. Mallet also advanced several terms still in use, such as seismic focus, angle of emergence, isoseismal line and meizoseisinal area.

Development of Seismology.

While Mallet's work was draw ing to a close, the study of earthquakes was continued in other countries. In Italy, L. Palmieri constructed his electromagnetic seismograph in 1855, and installed it in the new observatory on Vesuvius. From 1869 to 1878, T. Bertelli observed and measured earth-tremors with unfailing diligence. In 1874, M. S. De Rossi founded the Bollettino del Vulcanismo I taliano, the first journal devoted solely to earthquakes and volcanoes. He also devised his scale of seismic intensity, to be combined a few years later with one proposed by F. A. Forel. In 1878, A. Heim and Forel founded the Swiss Seismological Commission, by which Swiss earthquakes were studied for more than 3o years. It was then merged in the existing Government department of the Swiss earthquake service.Far more important was John Milne's foundation, in 188o, of the Seismological Society of Japan. It is not too much to say that, during its years' existence, seismology became an exact science. Accurately recording seismographs were invented by J. A. Ewing, T. Gray and Milne, and, for the first time, revealed the real nature of the movements of the ground during an earthquake. Most of the society's work was done by Milne, who organized a system of observers throughout a large part of the country, catalogued the great earthquakes of Japan and studied their distribution in space. Shortly before the Seismological Society ceased its useful work, the provinces of Mino and Owari were visited by the de structive earthquake of Oct. 28, 1891. A few months later the Imperial Earthquake Investigation Committee was founded. The objects set before it were to discover means of predicting earth quakes and to fix the design of earthquake-proof buildings. The committee, however, wisely took all seismology for their province, extended the system of observers begun by Milne, even studying the volcanoes of the country, and accomplished valuable work.

Somewhat briefer references must be made to some other com mittees founded for the study of earthquakes. After the Ischian earthquake of 1883, the Italian meteorological office was extended so as to include a special section of geodynamics. In 1895, the Italian Seismological Society started its Bollettino, one of the most useful of seismological journals. The Laibach earthquake of 1895 led to the creation of the Austrian earthquake service. The Seismological committee of the British Association was appointed in 1895. The services of the International Association of Seismol ogy, founded in 1903, were unfortunately ended in 1914. After the Californian earthquake of 1906, the Seismological Society of America began its promising career. In its Bulletin, many valuable memoirs have already been published.

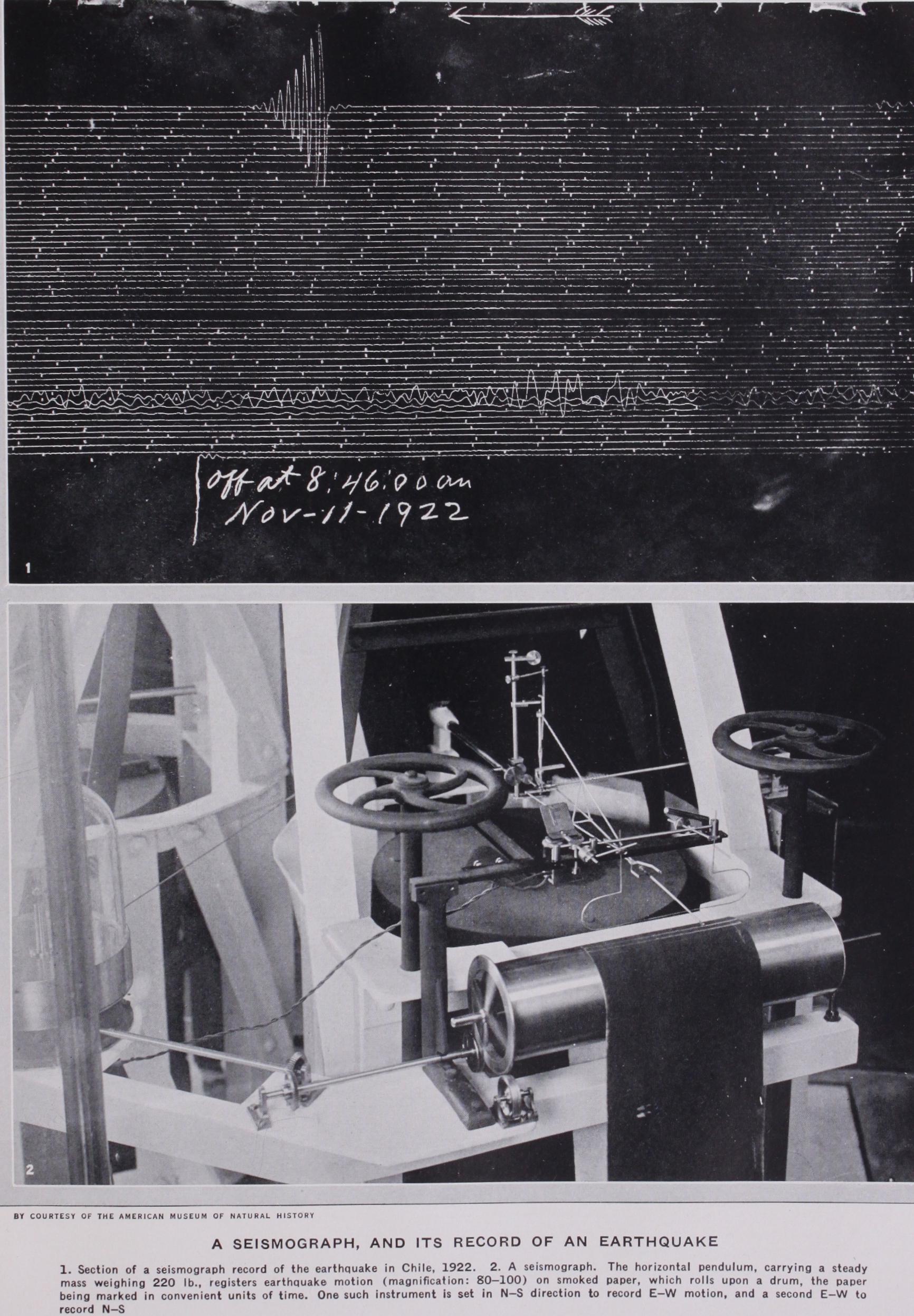

Lastly, the latest and most interesting development of seis mology—the registration of distant earthquakes—must be referred to. Isolated records of this kind had been made at various times from the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 to the Riviera earthquake of 1887. In 1889, systematic observations were begun with a horizontal pendulum by E. von Rebeur-Paschwitz, and carried on until his death five years later. Milne shortly afterwards had recorded distant earthquakes with his seismograph in Japan, and, on his return to England in 1895, he founded his well known ob servatory at Shide in the Isle of \\Tight. Here, aided by grants from the British Association, he carried on the work of the Seis mological committee until his death in 1913. His seismograph was erected at observatories in all the chief British possessions and at many foreign stations. To-day, the Milne-Shaw seismographs, of an improved pattern, and many similar instruments, are to be found in every civilized country. The light which these have thrown on the nature of the earth's interior, can hardly be over estimated.

Some Typical Earthquakes.

Before describing these earth quakes, it may be convenient to mention a few of the special terms in general use. An earthquake is due to some sudden displacement within the earth. The region within which this occurs is usually called the seismic focus, or simply the focus, sometimes also the origin, centre or hypocentre. The point on the surface vertical ly above the centre of the focus is the epicentre. A line drawn through all places at which the intensity of the shock is the same is termed an isoseismal line. The area within which the shock is strongest, say, that bounded by the innermost isoseismal line, is known as the meizoseismal area, and that within which the shock is perceptible without instrumental aid as the disturbed area When earthquakes occur in series, the most important member is the principal shock. The others are divided into fore-shocks and after-shocks according as they occur before or after the principal shock.Lisbon, l755.—One of the greatest of all known earthquakes was that which ruined Lisbon on Nov. 1, 1755. The epicentre was submarine and some distance to the west of Lisbon. How far the shock was actually felt is uncertain, for many observations, such as those reported in England, cannot refer to the earthquake. It seems, however, to have been felt all over Portugal and Spain, and in the south of France and the north of Africa, so that the disturbed area was probably more than a million sq. miles. The earthquake came without warning. Three great shocks in succes sion threw down all the houses in the lower part of Lisbon. Ob servers near the coast noticed that the sea retired, laying bare the bar, and then rolled in, it is said, to a height of 4oft. above the ordinary level. For the whole of that day and the next night the sea continued to ebb and flow. Similar waves were observed along the coast of Spain, at Tangier and Funchal, along the coast of Holland, the south and east coasts of the British Isles, and even across the Atlantic to Antigua, Martinique and Barbadoes. Such waves occur with every great submarine earthquake. The feature of the Lisbon earthquake that is unique, or almost unique, among known earthquakes, is the agitation of inland waters far beyond the limits of the disturbed area. In Italy and Switzerland, lakes were set in oscillation, pools, rivers and lakes in Great Britain, as far as Loch Ness, I,32om. from the epicentre, and even the lakes of Sweden and Norway, at a distance of I , 7 5om. In Loch Lomond (1,22om.), the water rose to a height of 2ft. 4in., then subsided, and continued to rise and fall every ten minutes for an hour and a half.

Southern Calabria, 1783.—Less than 3o years later, in 1783, southern Calabria was desolated by a series of violent shocks. From Feb. 5 to March 28 there were six great earthquakes, and, up to Oct. 1, 1786, there were besides at Monteleone 38 very strong shocks, 198 strong, 303 of moderate strength and 642 slight shocks, a total of 1,187 earthquakes. The first great shock on Feb. 5 occurred without any warning, except for occasional slight shocks from 178o onwards. Lasting about two minutes, with undulations vertically upwards and from every direction, all houses on the plain were destroyed within a few seconds, while those built on the firm ground of the hills escaped serious damage. The meizoseismal areas of the six great earthquakes were all of small size, and the intensity declined so rapidly outside them that one town might be entirely ruined while another only 5m. away suffered little. The disturbed areas were small, not one of them exceeding roo,000sq.m. From this, it is clear that the foci were situated close to the surface. The most interesting feature about these earthquakes was the rapid migrations of the foci. The first occurred on Feb. 5 near Palmi ; the second on Feb. 6 near Scilla, rom. to the S.W. ; the third on Feb. 7, at 8.20 P.M., near Monte leone, 35m. N.N.E. of Scilla ; the fourth, at To P.M. on the same day, near Messina and Scilla; the fifth, on March r, near Monte leone again ; and the sixth, which was as strong as the first, on March 28, near Girifalco, about 2om. E.N.E. of Monteleone. Thus the movements took place over a length of 65 miles.

Since 1783, many earthquakes of great interest have occurred, some of which have revealed to us new phenomena. It will be sufficient to refer here to the Assam earthquake of June 12, 1897, and the Japanese earthquake of Sept. 1, 1923, and to the slight shocks of Great Britain.

Assam, 1897.—On the Assam earthquake, we have an admi rable report by R. D. Oldham. It was an earthquake remarkable for the vast extent of its meizoseismal area and the distortions of the crust within it. The shock itself was felt over about one and three-quarter millions sq.m., or nearly half the size of Europe. Serious damage to buildings occurred in a district containing about i 6o,000sq.m., or more than twice the size of Great Britain. The meizoseismal area, lying about 250m. N.E. of Calcutta, covered more than 6.000sq.m., i.e., about the size of Yorkshire. From such figures. we can only conclude that. unlike the Cala brian earthquakes, the Assam earthquake originated at an unusu ally great depth. At Shillong, the ground vibrated visibly like a storm-tossed sea, only with more rapid undulations. At several places in the meizoseismal area, stones were projected from the ground, showing the maximum acceleration there must have been greater than 9,600mm. per sec. per sec. Within the meizoseismal area, distant places became clearly visible that before were hid den by intervening ridges. Changes in the slope of stream-beds led to the formation of pools. Fractures without superficial dis placement occurred in the solid rock, one 7m. in length. Close to it, trees were snapped in two, and large blocks of stone were rent or dislodged. Besides these fractures, fault-scarps were formed, one i 2m. long with a maximum throw of 35 feet. In many parts of the meizoseismal area, there were isolated centres of after-shocks, all, with the distortions described above, being evidently the results of some vast deeply-seated movement.

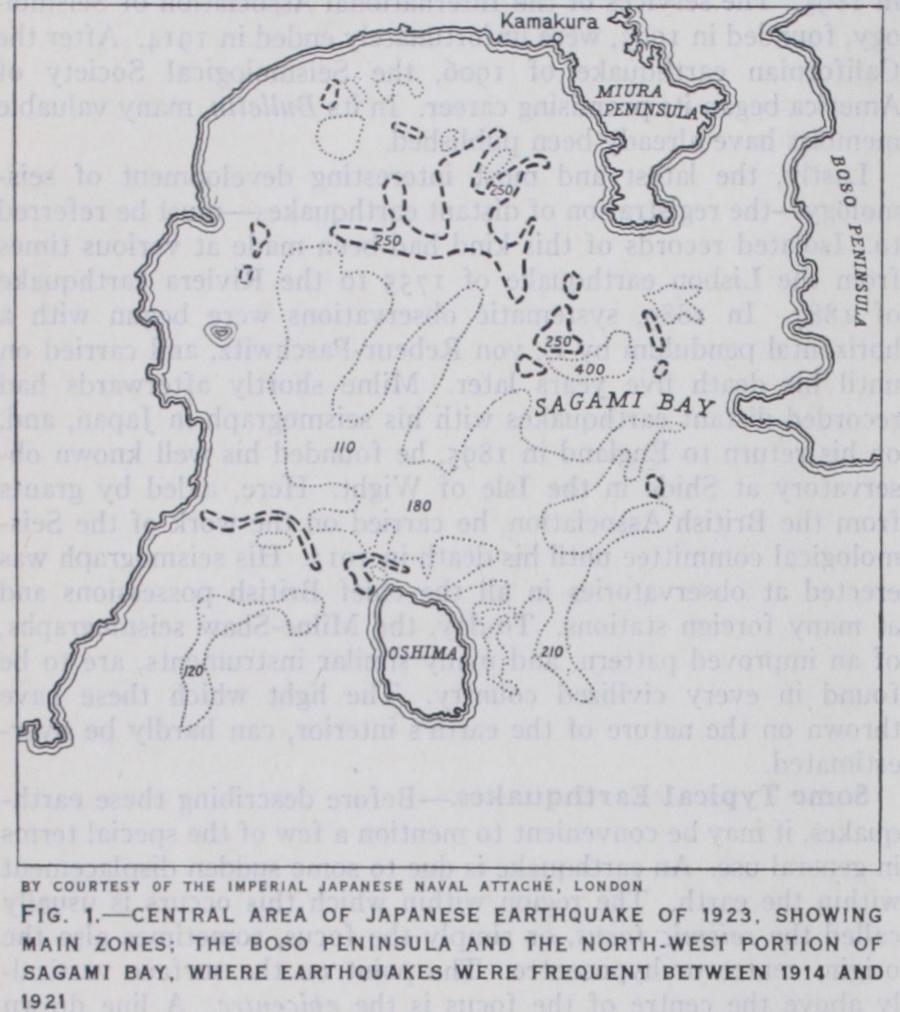

Japan, 1923.—In the present century, one of the greatest dis asters known to us was the Japanese earthquake of 1923, though most of the loss to life and property was due, not to the earth quake, but to the great fires that followed it. From seismo graphic records at Tokyo and elsewhere, it was found that the epicentre lay beneath Sagami bay, a short distance to the north of Oshima (fig. I), and that the mean depth of the focus was 3o miles. Soon after the earthquake, re-surveys were begun, both of the sea-bed and of the coastal regions of Sagami bay. The most remarkable changes were those in the bed of the bay. The broken lines in fig. i represent curves of elevation of 5o fath oms, and the dotted lines curves of equal depression. The figures within the curves give the greatest changes in fathoms. They reveal an uplift of more than 25o fathoms in one place, and, about a mile away, a depression of more than 40o fathoms, a dif ference of three-quarters of a mile. Clearly, a change of this magnitude could hardly occur without faulting. On land, the changes of elevation were much less marked. The main areas of uplift occurred along and beyond the north shore of Sagami bay and in the southern half of the Boso peninsula. In both, the greatest uplift measured was six and a half feet. Elsewhere, the change was usually one of subsidence, as a rule less than i6in., and only in one place reaching 5ft. 4in. In addition to the changes of level on land, the new survey revealed some horizon tal movements. The island of Oshima was shifted r 2ft. 5in. a little east of north, while the north shore of Sagami bay moved about 9ft. E.S.E. The displacements at these and other places show that the whole district made a clockwise twist about a vertical axis in Sagami bay.

British Earthquakes.—From 974 to r916, the total number of earthquakes known in Great Britain is 1,190, of which 310 occurred in England, 822 in Scotland and S4 in Wales. Not more than 22 of them attained destructive intensity, 13 in England, seven in Scotland and two in Wales, the strongest known being that which occurred near Colchester on April 22, 1884. In Scot land, nearly all the earthquakes are connected with well known faults. Close to Inverness, four strong earthquakes have occurred from 1816 to 19o1, probably through slips of the great fault that crosses Scotland along the line of the Caledonian canal. The most celebrated earthquake district in the country is the village of Comrie in Perthshire, which lies close to the Highland border fault. Here, from 1 788 to 1921, 421 earthquakes were felt or heard, three-fourths of them between 1839 and 1846. A third region lies on the south side of the Ochil Hills. From Bridge of Allan to Alva, nearly 200 earthquakes have been observed during the present century. In England and Wales, there are many earthquake-centres, the most important being near Hereford, in the midland counties of England, and in the southern counties of Wales. Some of the strongest earthquakes in England and Wales are those known as twin-earthquakes. In these, the shock con sists of two distinct parts separated by an interval of two or three seconds. The impulses which cause them originate at some depth, in two detached foci from about 8m. to 2om. apart, and in many of them so closely together that the second focus is in action before the vibrations from the first have time to cross the intervening space.

Nature of Earthquake Motion.

In slight earthquakes, a low rumbling sound is usually heard, in a second or two, the sound becomes louder and with it a weak tremor is felt, the tremor rapidly merges into a few distinct vibrations and then movement and sound die away, the whole lasting from five to ten seconds. In great earthquakes, the order is the same, but the vibrations are strong oscillations, each of which may last a second or more, and the total duration may amount to four or five minutes. In the greatest of all, the ground may suddenly move as a whole and with such violence that no work of human hands can withstand the motion.Seismographic records of earthquakes also reveal three stages of motion. In the preliminary tremor the vibrations are small in amplitude and short in period, from five to 12 occurring every second. It is succeeded by the principal portion, in which the vibrations are of much greater amplitude and from half to one or even two and a half seconds in period. In the end portion, the vibrations are of small amplitude but remain of long period. In most earthquakes, the range or double amplitude of the vibra tions is less than Imm.; in a semi-destructive earthquake, it may reach 73mm., and, in a destructive earthquake, 223mm. (about 9in.) or more. The intensity is usually measured by the maxi mum acceleration of the vibrations. In an earthquake that is just sensible, this is about 17mm. per sec. per sec. In destructive earthquakes, the maximum acceleration must exceed 3oomm. per sec. per sec., but it often reaches much higher figures, such as 2,000mm. per sec. per sec. in the Californian earthquake of 1906 and the Messina earthquake of 1908, about 3,840mm. per sec. per sec. in the Japanese earthquake of 1923 and more than 9,600mm. per sec. per sec. in the Assam earthquake of 1897. These figures represent the intensity in the central areas of the earthquakes. To show how the intensity declines as the distance from the epicentre increases, series of isoseismal lines are drawn, the intensity along each depending on the degrees of some arbitrary scale, such as the Rossi-Forel or the Mercalli scale. The out ermost isoseismal line bounds the disturbed area. In Great Britain, the largest dis turbed areas known are about I oo,000sq.

miles. In destructive earthquakes the area may amount to as much as ogle and three quarters or two million sq.m., as in the Assam earthquake and the Kangra earth quake of 1905.

The sound that accompanies an earth quake is a very deep rumbling noise, so deep that it may pass unheard by many ob servers. When it is heard, some of the vibrations may be inaudible, and thus the sound may be referred to different types, such as a lorry or train passing, thunder, wind or a chimney on fire, loads of stones falling, the fall of a heavy body, an ex plosion, etc. The variation in audibility throughout the disturbed area may be rep resented by a series of isacoustic lines, along each of which the same percentage of observers hear the sound. In great earth quakes, the sound-area occupies a rather small region surrounding the epicentre; in slight ones, it may extend beyond the dis turbed area on one or all sides. Occasion ally, the sound alone is heard, and series of such earth-sounds have been observed in the island of Meleda in the Adriatic sea, East Haddam in Connecticut and Guanajuato in Mexico.

Dislocations of the Crust.

In some of the greatest earth quakes, there are no features more remarkable than the disloca tions of the crust, the renewal of movement along the fault that may follow one general direction for many miles. The displace ment along the fault may be mainly horizontal, as in the Cali fornian earthquake of 1906, vertical as in the Assam earthquake of 1897, or partly vertical and partly horizontal, as in the Mino Owari (Japan) earthquake of_ 1891. In a few earthquakes, such as the Messina earthquake of 1908, the movement takes the form of a warping of the crust, no actual fault being visible on the surface.When the movement is horizontal, the fault may appear as a crack or fissure or may be revealed by the severing of roads, fences, etc., the ends of which may be separated by several feet. The Californian earthquake of 1906 was due in part to a move ment along a remarkable fault, the San Andreas rift (fig. 2) . The portion of the rift displaced runs close to the coast, and its total length is about 27o miles. The rift has been traced still farther to the south for another 3oom. into the desert region of southern California. Here, the features of the rift retained their sharpness for many years, and there are clear signs of horizontal displacement in the past. For instance, in one place four deep ravines that descend the mountain slopes on the east side of the rift are displaced abruptly at the fault-line and reappear on the west side of the fault about 5oyd. farther to the north-west. Such movements are no doubt the sum of many displacements. In 1906, the total horizontal shift varied as a rule from six to i 5f t., in one place reaching 21 feet. From the shifting of fences, etc., it was unknown which side had moved, but a new survey of the district proved that the rock on both sides had been dis placed, that on the south-west side to the north-west, and that on the north-east side to the south-east. The movements decreased with increasing distance from the rift, ceasing at about 4m. on the north-east side, but at not less than 23m. on the other.

Much more remarkable in appearance, but less persistent in range, are the vertical displacements of the ground. When the throw is small, the result may be a mere slope of the surface; but, if it should exceed two or three feet, it appears as a low scarp or cliff. While the elevation is usually in one direction only, its amount is subject to wide and rapid variations. One of the faults of the Assam earthquake of 1897, the Chedrang fault, was about 12m. long. The movement was everywhere vertical, and the east side was invariably left the higher, except in two places where there was no throw. In the three portions into which the fault was thus divided, the maximum uplift was 2 5f t. in the southern portion, 35ft. in the middle and 32ft. in the northern. In this fault, it is unknown whether the east side was raised or the west lowered. In the Alaskan earthquakes of 1899, the meas urements were all made with reference to the sea-level. Six years later, dead barnacles still clinging to the rocks showed that, on the west side of Disenchantment bay, there had been an uplift (the greatest known to us) of 47ft. 4in. Here again, there were rapid variations, from 42ft. on the same coast to Soft. a mile to the west, and to 9ft. a quarter of a mile farther.

The displacements that are partly horizontal and partly vertical are more common than either of the others. One of the most re markable examples is that which occurred with the Mino-Owari earthquake of 1891. This fault, which almost crosses the main island of Japan in a general north-westerly direction, was traced for a distance of 4om., and there can be little doubt that its total length was 7o miles. Its course is independent of the slope of the ground, for it cuts across hill and valley alike. Throughout its whole length, the ground on the north-east side of the fault was shifted to the north-west relatively to the other, usually 3ft. or 4ft., sometimes as much as 13ft. In some places, there has been no uplift, but, when it is perceptible, it is always a depression of the north-east side by from 3ft. to 2of t., except in one place, where the north-east side was left 2oft. above the other.

In a few earthquakes, a new series of levels has revealed a general bulging or subsidence of the crust without superficial fracturing. In the Kangra (India) earthquake of 1905, a slight rise of not more than sin. was measured. In the Messina earth quake of 1908, there appears to have been a general subsidence, of as much as 2ft. at Reggio and 2ft. 4in. at Messina.

Sea-Waves.

When the origin of an earthquake is submarine, the shock along the coastal region may be followed by the inrush of a sea-wave, often, but erroneously, called a tidal wave. Esti mates of the height of the wave are usually excessive, but, in the Messina earthquake of 1908, the height was certainly 28ft. on the Sicilian coast and 35ft. on the other. In the Sanriku (Japan) earthquake of 1896, the height was not less than 93 feet. So strong are the waves that vessels may be driven inland 2ooyd., trees may be uprooted, or a mass of concrete, iocu.yd. in volume, may be torn from a pier and drifted 2oyd. away. The sea-waves sometimes travel to great distances. The sea-waves of the San riku earthquake were registered at San Francisco (4,787m.), and those of South American earthquakes have been recorded in Japan after travelling distances of about Io,000 miles. After such journeys the water slowly sweeps up a beach and back again, like tides of short period, of 20 or 3om., the total rise and fall being as much as eight feet. There can be little doubt that the sea-waves are caused by some displacement of the ocean-bed, like that which occurs on land when fault-scarps are formed, for changes of level have occurred on land with many earthquakes followed by sea-waves. On the other hand, in the Californian earthquake of 1906, the fault was in part submarine, but the crust displacements were horizontal and no sea-waves were observed.

After-Shocks of

a great earthquake, the ground near the epicentre may remain for days in almost inces sant motion. So frequent are the after-shocks, sometimes so con tinuous, that it may be impossible to count them without instru mental aid. After the Mino-Owari earthquake of Oct. 28, 1891, a seismograph at Gifu recorded 3,365 shocks by the end of 1893. Other Japanese earthquakes have been similarly followed, the earthquake of 183o by 68i shocks in six months, that of 1847 by 93o in 31 days, and that of 1923 by 1,256 at Tokyo in the first month. Even in Great Britain, the Inverness earthquake of 19o1 was succeeded by 16 shocks in less than two months. On the other hand, with the Californian earthquake of 1906, there were comparatively few after-shocks, the greatest number observed at any place in 14 months being 153. As there were vertical dis placements of the crust in the Assam and Mino-Owari earth quakes, and none of any consequence in the Californian earth quake, it would seem that the number of after-shocks depends on the direction of the crust displacement. Usually, after-shocks are of slight intensity, but they sometimes reach destructive strength and are then followed by their own trains of after shocks. After the first few days, they decline rapidly in fre quency. At Gifu during the first week after the Mino-Owari earthquake, the daily numbers were 318, 173, 126, 99, 92, 81 and 78. Omori has shown that, if small variations are neglected, the decline in frequency may be represented by the formula y — x+h, where h and k are constants and y is the number of after-shocks within a given interval at time x after the earthquake. Their epi centres lay along all parts of the fault described above, they were frequent for some time near the terminal regions and finally were almost confined to the central district. A similar law gov erned the distribution of the after-shocks of the Inverness earth quake of 1901, and these were also marked by a continual approach of the foci towards the surface of the earth.

Secondary Effects of Earthquakes.

Whenever strong earthquakes occur in hilly districts, they may give rise to ava lanches so large and so numerous that hillsides previously cov ered with forest are left bare. Avalanches along one side of a valley may divert a river-course, from both sides they may pond back the river into lakes. When the earthquakes occur among snow-covered mountains, as in Alaska in 1899, the de scending glaciers may be shattered, and snow-avalanches may cause a temporary advance of the glaciers.Even on level ground, many changes occur through the corn pression of the alluvium. Rice-fields in Assam and Bengal that were level before the earthquake of 1897 became gently undu lated, the difference between crest and hollow being two or three feet. Railway lines are often buckled or twisted into loops. The ground is extensively fissured. When they occur near a river, the fissures run parallel to the bank, being due to the oscillation of ground unsupported on one side. Usually, they are a few hun dred yards in length and two or more feet wide. They are dis tinguished from the permanent dislocations of the crust by their short length and variable direction. Others are formed on hillsides by incipient landslips and are horseshoe-shaped. They may also occur quite apart from any slope or excavation. They are then aligned in parallel series, and have been seen to open as the visible waves passed. The underground water-system is naturally dis turbed by such changes. As a rule, the level of water in wells rises, but occasionally the supply is reduced, the variations being con nected with changes in the width of the underground water-chan nels. When the surface-beds overlie water-bearing sands, the com pression of the latter forces water through the fissures above in jets that may rise to a height of several feet and bring up sand and earth with them. As the current of water diminishes, the sand is left round the opening in the form of a shallow crater or saucer, sometimes loft. in diameter: Distribution of Earthquakes.—How unequally earthquakes are distributed over the world is well known. There are coun tries, like Italy, China, Japan or Peru, in which earthquakes are of frequent occurrence and of destructive strength. There are others, such as Switzerland, in which earthquakes are numerous but seldom cause damage ; and there are a few, like Egypt or Brazil or the centre of Russia, in which they occur but rarely and are always weak. To give some numerical illustrations : in the years 1891-1920, 4,954 earthquakes were observed in Italy, an average of 165 a year; in the years 1893-98, 3,187 earthquakes were felt in Greece, or 531 a year; in the years 1885-92, 8,331 earthquakes were recorded in Japan, or 1,o41 a year. In Switzer land, 998 earthquakes were felt in 1880-1909, an average of 33 a year; in Great Britain, 366 in 1889-1916, or 13 a year. In Brazil, 39 earthquakes were recorded during the 19th century. If we confine ourselves to the earthquakes that desolate cities, there were during the last century 39 in China, 22 in Japan, 21 in the Philippines, 19 in Greece, 16 in Italy, II in Chile and 8 in Peru.

In his earthquake-map of the world, Mallet coloured the dis turbed area of each earthquake with a tint depending on its in tensity. Such a method of mapping obscures details, but never theless the map led to results of general interest, namely, that earthquakes occur in bands of from 5° to 15° in width, that these bands follow as a rule the lines of elevation that divide the great oceanic or continental areas of the earth and so lie along the lines of mountains and volcanic vents, and that the areas of least disturbance are the central portions of great oceanic and continental areas or large islands in shallow seas. More detailed results are obtained from the methods of mapping meizoseismal areas or epicentres. Montessus' world-map is based on his great catalogue of nearly i6o,000 earthquakes. The principal conclusion at which he arrived is expressed in the following law : The earth's crust trembles almost only along two narrow bands which lie along great circles of the earth, the Mediterranean or Alpino-Caucasian Himalayan circle and the circum-Pacific or Ando-Japanese-Ma layan circle. Earthquakes are not uniformly distributed along these bands; there are gaps in them in which few or no shocks occur. But that the great seismic zones cling to them is evident from Montes sus' figures. Out of every 1 oo earthquakes, 53 occurred along the Mediterranean circle, 38 along the circum-Pacific circle and nine elsewhere. In this map, Montessus made use of all recorded earth quakes whatever their intensity. Milne relied only on earthquakes registered by seismographs over an area not less than about one tenth of the whole surface of the earth. In essentials, his map is not unlike that of Montessus. There is the same great terrestrial region ranging west and east from Italy to the Himalayas and con taining 21 % of all the earthquakes. Six regions border the Pacific ocean with 68%, while four small oceanic regions include the re maining I I % of the earthquakes.

These maps show the distribution of earthquakes on a large scale. Coming to details, the most important law is that which Montessus expressed thus : "in a general way, we may say that, of two contiguous regions . . . the more unstable is that which presents the greater average slope." Milne, dealing with the earth quakes of Japan, came to a similar conclusion. The earthquakes of Japan, indeed, furnish one of the best examples of the law. Of the strong earthquakes from 1885 to 1905 (257 in number), Omori found that 145 originated in zones bordering the Pacific coast and only nine n the Japan sea coast. The Japan sea oc cupies a depression no place deeper than 1,646 fathoms, the gradient of the sea-bed ranging from i in 67 to I in 220. On the other side, the sea-bed slopes rapidly, with gradients of in 27 and i in 16, into the basin of the Tuscarora Deep (4,376 fathoms) .

One other law of distribution should be referred to. It is gen erally supposed 'that there is an intimate connection between earthquakes and volcanoes. Milne's seismic map of Japan shows, however, that "the central portions of Japan, which are the moun tainous districts where active volcanoes are numerous, is singu larly free from earthquakes." In Central America, the old town of Guatemala, built on the flank of an extinct or almost extinct volcano, was ruined seven times by earthquakes from 1541 to 2775. The new town, close to an active volcano, has never been destroyed.

Frequency of Earthquakes.

If we confine ourselves to earthquakes perceptible to man, one of our earliest estimates is that of Perrey, who in 1843 assigned a frequency of only 33 earthquakes a year to the whole of Europe and adjacent parts of Asia and Africa. For the first half of the 19th century Mallet re corded 65 a year. In 1900, Montessus estimated the annual num ber of earthquakes at about 3,83o. Including slight tremors, Milne suggested that there were not less than 30,00o a year, or about two a minute. Of great earthquakes—those which reduce towns to ruins—Mallet recorded one a year in the first half of the 19th century, and Milne four a year during the last quarter. A noteworthy point about destructive earthquakes is their ten dency to occur in groups. In Italy, according to G. Mercalli, from 16o1 to 1881, 182 destructive earthquakes occurred in 103 years and 27 in the remaining 178 years. Similarly in Japan, as Omori remarks, the destructive earthquakes since 1301 have occurred in 41 groups separated by an average interval of about 13 years. This tendency to clustering, as Milne showed, is char acteristic of the great earthquakes of the whole world. They occur in groups of two or three to 15 or more; the groups last from one to three days, seldom more than six days, and the in terval between successive groups ranges from two to seven weeks. Milne also pointed out that, in widely separated regions, such as Italy and Japan or the opposite sides of the Pacific, alternations of activity were to some extent synchronous.

Periodicity of Earthquakes.

The clustering of earthquakes leads naturally to their periodicity, to the inquiry whether there is any regularity in the recurrence of clusters. Whatever the causes of such periodicity may be, it is not to be supposed that they produce the earthquakes, but merely that they tend to precipi tate movements that are almost on the point of taking place. They may be more or less superficial in their action, or they may be deeply-seated within the earth or even quite outside it. We have thus two groups of periods, one of a year and a day, the other of 21 minutes, 429 days and 11, 19, etc., years.Of these periods, the annual period has been longest known, since 1834, when P. Merian noticed that the earthquakes felt at Basle were more frequent in winter than in other seasons. This variation has been confirmed by many other seismologists. The chief result is that the maximum epoch, or epoch of greatest fre quency, occurs in winter in both hemispheres. But there are many exceptions to this law. It does not apply to the most de structive of all earthquakes, and, in insular and peninsular re gions, the frequency is greatest in summer. The diurnal period is less pronounced than the annual period, and can only be de tected in earthquakes recorded by seismographs, for shocks are naturally felt more frequently during the quiet hours of the night. For ordinary earthquakes, the maximum epoch occurs near local noon in each district. For the after-shocks of strong earthquakes, it occurs at first shortly after midnight, but after a few months returns to noon. Several causes have been suggested for these periods, the variations of atmospheric pressure being the most probable.

The second group of periods, depending more or less on the structure of the earth or on its relations to the rest of the solar system, are of great interest. The shortest is one of 21 min utes. The period of 429 days was noticed by Milne in 'goo. He showed that great earthquakes are frequent near the times when changes occur in the direction of the polar movements. Shortly afterwards, Omori found that the connection holds for strong, but not for slight, earthquakes in Japan. Recently, other periods have been added to the list. Making use of the destructive earth quakes from 1701 to 1899 recorded in Milne's great catalogue, it has been shown that there are periods of i 1, 22, 33 and 19 years in the earthquakes of the northern hemisphere, the first maxima of which occurred in 2709, 1716, 1724 and 1715-16, respectively. The epochs are the same for different centuries, for different seasons of the year and for every large region of the northern hemisphere.

Position of the Epicentre.

The first element to be de termined in the study of an earthquake is the position of its epicentre. Various methods have been suggested, depending on observations of the time, direction or intensity of the shock.Time-records, as a rule, are not accurate enough for the pur pose. They have been used by Seebach and others with results of doubtful value. It is easier to estimate the interval between two events than the precise time of either, and thus the only time-method used with profit is one proposed by Omori. This depends on the duration of the preliminary tremor at not less than three stations. If x is the duration in seconds of the tremor at a place not more than i,000km. from the origin, Omori showed that the distance in kilometres between the station and the origin is 7.27x+38. Knowing, then, the distances of the origin from three stations, circles drawn with the stations as centres and the corresponding distances as radii, should intersect close to the epi centre. This method is much used in Japan, especially for locat ing the epicentres of submarine earthquakes. The second method, depending on the lines of direction of the shock at two or more places, was used by Mallet in his investigation of the Neapolitan earthquake of 1857. Most of the 78 lines of direction in this earthquake passed close to the village of Caggiano. Greater ac curacy can be obtained by using the means of a large number of observations. In the Hereford earthquake of 1896, the position of the principal epicentre was fixed by the lines of mean direction in London and Birmingham. The last method, which makes use of the intensity of the shock, is the one most frequently applied. In a violent earthquake, the area of greatest destruction must include the epicentre. In weak or moderately strong earthquakes, the centre of the innermost isoseismal line cannot be far distant from it.

Depth of the Focus.

Up to the present time, though many attempts have been made to determine the depth of the focus— one of the most interesting problems of seismology—we can lay claim to no more than approximate results. The methods sug gested for the purpose depend, as with the epicentre, on observa tions of the time or intervals of time, and on the direction and intensity of the shock. Seebach's method is of theoretical, rather than practical, interest, owing to the difficulty of obtaining exact time records. It has been used for five German earthquakes, giv ing depths ranging from seven to 24 miles. For near earthquakes, Omori's method, involving the duration of the preliminary tre mor, is less open to objection. Knowing the distance of the focus by the duration of the tremor and also the distance of the epicentre, it is a simple matter to estimate the depth of the focus. In this way, he found the mean focal depth in 729 non-eruptive earthquakes of the volcano Asama-yama to be about 2m. below the base of the mountain. He also applied the method to 21 earthquakes felt in Tokyo, and found the depth to lie between 10 and 3' with an average value of 20 miles. The well known method devised by Mallet was the first in actual use. In his study of the Neapolitan earthquake, he measured the inclinations of fissures in many buildings. Assuming the direction of the shock to be at right angles to the fissures, he obtained 26 lines of di rection which he took to point directly to some part of the focus. The position of the epicentre at Caggiano being known, he found the depth of the focus to lie between 3.2 and 9.3m., the mean value of all the estimates being 6.6 miles. Mallet's method has been employed in several later earthquakes, the results being about one-third of a mile for the volcanic Ischian earthquakes, and from 63m. to io4m. for four other earthquakes. Similar to Mallet's method is one used by Milne, in which the lines of direction were obtained from the horizontal and vertical com ponents of the motion as given by seismographs. In the Yoko hama earthquake of 1880, he found the depth to lie between 1 and 5 miles. Two later estimates, by Omori, are 5.6 and miles.Of the methods depending on variations in the surface inten sity, the best known is that devised by C. E. Dutton in his in vestigation of the Charleston earthquake of 1886. Assuming that the intensity of the shock varies inversely as the square of the distance from the focus, Dutton showed that the rate of decline in the intensity of the shock is greatest at a distance from the epicentre which, when multiplied by 1.732, gives the depth of the focus. In the Charleston earthquake, there were two foci, the depths of which were calculated in this way to be 12m. and 8 miles. In five later earthquakes, the depths were found by the same method to lie between 4m. and aim. Dutton's method, apart from the difficulty of applying it, is open to the objection that it takes no account of the loss of energy that the waves suffer in traversing the crust. From a comparison of the intensi ties at the epicentre and along an isoseismal line, the objection has been partly met by R. D. Oldham, who found that of 5,605 recent Italian earthquakes, 90% originated at depths less than 63m. and only 1% at depths greater than 19 miles.

Teleseismology.

We come now to the most recent and fas cinating development of seismology—the registration of distant earthquakes. The instruments by which they are recorded are described under the heading SEISMOMETER (q.v.). Here, we are concerned only with the results obtained from a study of the seismograms or records. A brief glance at one of them shows a series of waves, small at first, then rapidly increasing in magni tude, and concluding with long, slow undulations—corresponding to the preliminary tremors, the "principal" portion and the "end" portion of the early writers on the subject. A closer inspection shows that the preliminary tremors consist of two phases. The first phase, known as the first preliminary tremors or primary waves, begins with a small but sudden displacement, followed by rapid vibration of a few seconds in period, and including at times re inforcements of the motion. The second preliminary tremors or secondary waves begin with a comparatively large vibration, suc ceeded by irregular vibrations, among which sudden reinforce ments may appear as in the first phase. As the secondary waves end, the third phase, that of the long waves or large waves, begins, at first with large and irregular undulations of perhaps more than half a minute in period. Then come still larger waves, 12 to 20 sec. in period, concluding with smaller and irregular undulations forming the end portion. The whole movement may last one or two hours, sometimes more. In great earthquakes, after the end portion closes, a detached group of small long period waves may be seen, followed, perhaps, by a second group of still smaller range. There are other movements traceable in the records, but these are the principal features.The first vibrations of the above phases are usually denoted by the letters P, S and L, respectively, the reinforcements in the earlier phases by PR, SR or PR,, etc., when there is more than one. The groups of small waves following the end portion are denoted by and referring to the first passage of the long waves.

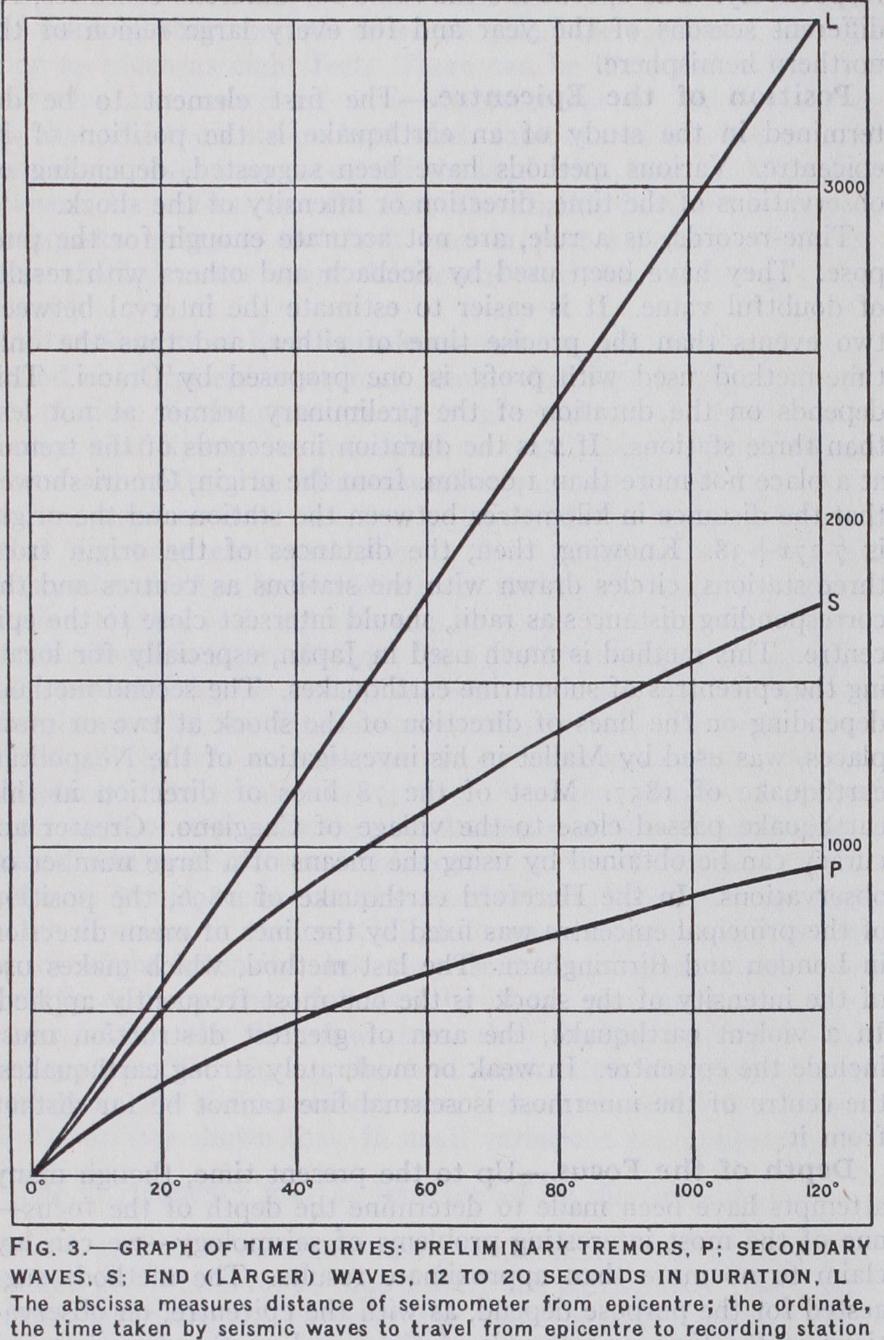

One of the most interesting points about the P and S waves is that they do not travel with uniform velocity along the surface of the earth. The variations in velocity may be represented by time-curves or hodographs. In these, the distance of a station from the epicentre along the great circle joining them is meas ured along the horizontal axis of the diagram, and the time taken by the waves to travel this distance along a line at right angles to that axis. A time-curve may be drawn in this way for any earthquake. The curves in fig. 3 are average time-curves. In them points are plotted corresponding to the times of traversing given distances for a number of earthquakes, and the curves are drawn through or near these groups of points. The time-curve for a given earthquake may thus differ slightly from the average curves, the divergences depending in part on the depth of the focus, and, indeed, furnishing some clue as to that depth.

The first point to be noticed in these curves is that, while the line L is straight, the lines P and S are both so curved that, as the surface distance increases, the time required to traverse it does not increase in the same proportion. In other words, as the sur face distance increases, the velocities of both P and S waves also increase. Near the epicentre, the velocities of these waves are, respectively, 7.1 and 4•okilo. per sec. At distances of 3o°, 6o°, 9o° and 120°, the velocities of the P waves along the surface are, respectively, 8.6, 10.9, 12.6 and 13.6kilo. per sec. ; those of the S waves are 4.8, 6.o, 6.9 and 7.7kilo. per sec. The only in ference that we can draw from these increases is that both waves travel, not along the surface, but along curved paths through the earth, and that the velocities increase generally with the depth below the surface.

Earthquake Waves.

From the straightness of the line L in fig. 3, we conclude that the time taken to travel any distance along the surface is proportional to that distance, that is, that the long waves travel along the surface with constant velocity, namely, 3.8kilo. per sec. Now, the great circle that passes through the epicentre and a given station is divided into two arcs, the minor and the major arcs. The first long waves that reach a station are of course those that travel with the above velocity along the minor arc. The waves continue their journey to the antipodes of the epicentre, cross there and pursue their way back towards the epicentre. They thus pass the given station a second time, that is, after traversing the major arc, and appear on the record there as the waves called the mean value of the velocity being 3.7kilo. per sec. Crossing at the epicentre, they again travel along the minor arc and, if strong enough, are recorded as the waves their mean velocity being 3.4kilo. per sec. The lower velocity for the waves is no doubt due to the fact that they are the rep resentatives of the most prominent but later of the long waves L. The mean time taken by the long waves to travel completely round the globe (that is, is 3hr. 20min. 46sec.Returning to the P and S waves and their curved paths through the body of the earth, we have the valuable suggestion by R. D. Oldham, in 1899, that the primary waves consist of compressional vibratio is and the secondary waves of distortional vibrations. It is now recognized that both types of vibrations (owing to re peated reflections and refractions in the outer layers of the crust) occur in both primary and secondary waves, but that compres sional vibrations predominate in the former and distortional vibra tions in the latter.

Estimates have been made by several seismologists as to the forms of the paths followed by the primary and secondary waves, those by C. G. Knott, founded on Turner's tables, being the most detailed. Assuming that the earthquake originates at a small depth below the surface, he has calculated the forms of ten curves or rays for the primary waves and seven for the secondary waves. He found that all the rays that emerge at the surface at distances less than 6o° from the epicentre are concave towards the surface throughout. The ray that emerges at a distance of is, in its deeper portion, slightly convex towards the surface, and this shows that, at a depth of about three-tenths of the earth's radius, the velocity has ceased to increase with the depth. This is further shown by the comparative straightness of still deeper rays in their central portions.

Two other points in connection with these waves must be re ferred to. The first is that, at distances of more than from the epicentre, the secondary waves seem to disappear. The sig nificance of this fact will be referred to later. The second is that, besides the waves either primary or secondary that proceed di rectly towards a station, there are others of the same types that reach the surface at some intermediate place, are reflected there, and, travelling on to the station, appear as reinforcements of the motion known by the letters PR, SR, etc.

Observational Methods.—Several methods have been used to determine the position of a distant epicentre. It will be sufficient to refer to two that are frequently employed. The first method, which is practically the same as Omori's for near earthquakes, depends on the duration of the primary waves ; that is, on the in terval S-P. For the average earthquake, this is shown to be constant at the same distance from the epicentre. For instance, if S-P were 6min. 42sec., then the distance measured along the surface would be 45° or 5,000km. If the distances were known for two other stations, the epicentre must lie near the point of intersection of the three circles drawn with the stations as centres and the corresponding distances as radii. In practice, it is found advisable to make use of the observations at several or many stations. By the second method, Galitzin's, the position may be determined from observations at one station only. The distance of the epicentre is given, as before, by the value of S-P. The direction of the epice:tre is taken as that of the resultant of the N—S and E—W components of the first displacement. The epi centre must therefore lie at one end of the diameter in this di rection of the circle of radius corresponding to S-P, which of the two ends is decided by the vertical component of the initial motion.

Seismographic observations on both near and distant earth quakes have thrown much welcome light on the nature of the earth's interior. They have shown that there is, first, an outer crust consisting of two layers, an upper granitic layer roughly Tim. in thickness and a lower basaltic layer about twice as thick. Below the latter lies the homogeneous layer of great thickness. It probably reaches nearly half-way to the centre of the earth, for, at about this depth, the rigidity begins to break down. Within it is the central core. This allows the primary waves to pass, but with a velocity one-third less than that just outside it. It does not, however, transmit the secondary waves, as is shown by their disappearance at the distance of about 12o° from the epicentre, and, on this account, it has been supposed that the core is fluid.

Origin of Earthquakes.—The distinction between volcanic earthquakes and earthquakes that occur far away from active vol canoes has long been recognized. In 1878, R. Hoernes divided earthquakes into rock-fall, volcanic and tectonic earthquakes. The first may be neglected as of little consequence, but lately an important addition has been made of very deep-seated move ments, the origin of which may be at a depth that may be a per ceptible fraction of the earth's radius. To these, Oldham has given the name of bathyseisms. The different classes, however, cannot always be kept distinct. Tectonic earthquakes may occur in immediate connection with a volcanic eruption, and bathyseisms may merge into tectonic earthquakes.

Volcanic earthquakes are confined to the neighbourhood of a volcano, which may be active (as Etna), dormant (as Monte Epomeo in Ischia) or extinct (as the Alban Hills near Rome). In the first case, they usually precede a volcanic eruption and de cline in frequency as the eruption begins. The most significant features of volcanic earthquakes are their small disturbed areas (seldom more than ioo or 2oosq.m.) and their great intensity near the centre. These point unmistakably to very shallow foci, as a rule, only a fraction of a mile ; that is, to foci within or just below the mass of the volcano. With regard to the origin of most volcanic earthquakes, there can be little doubt. The slight shocks felt before or with the eruptions are due to explosions or to the injection of lava into fractures or cavities in the volcano. The sharp earthquakes that follow an eruption after some months or that occur near dormant or extinct volcanoes are probably caused by the slipping of the rock adjoining a fracture, the slipping being due to the contraction or displacement of the magma.

Coming next to the origin of tectonic earthquakes proper, by far the most numerous of all, it is generally held that they are due to the formation of faults. In some rare cases, perhaps, they may be caused by the actual fracturing, but nearly always by the growth of the faults. With every step in such growth, it is evi dent that an earthquake must occur—a slight tremor or earth sound when the movement is a mere creep over a small section of the fault, a strong or destructive earthquake when the displace ment is considerable over an area many miles in length. Such a connection is evident when there are permanent dislocations of the crust along a pre-existing fault. In slight earthquakes, such as those which visit Great Britain, the displacement may be no more than a small fraction of an inch, and it must die out far below the surface. In such earthquakes, the longer axes of the isoseismal lines are usually parallel to well-known faults, the centres of the curves lie on the downthrow side of the faults; and, when a series of earthquakes occur in a district, such as with the Inverness earthquake of 190r, the epicentres migrate to and fro within a narrow band parallel to the direction of the fault.

In every earthquake country, it is found that a prolonged in terval of recovery follows a great earthquake. The interval may extend to hundreds of years, even to i,000 years or more. The Lisbon earthquake of 1755 has had no successor yet to compare with it in magnitude. Before an earthquake occurs, we may imagine a continual growth in the forces that will ultimately over come all resistance. Here and there on the fault-surface, there are obstacles that must first be cleared away, and each such re moval will give rise to a fore-shock. When the effective forces have become uniform over a large region of the fault-surface, it will then be possible for a general movement to take place, and it is to this movement that the principal shock is due. It is of course followed by a sudden readjustment of the stresses that produced the motion, to an increase chiefly along the lateral and upper margins of the focus. Thus it follows that after-shocks are at first more frequent near the terminal and central regions of the meizoseismal area, that they gradually forsake the former and become concentrated in the central portion, as in the Mino-Owari earthquake of 1891 and the Inverness earthquake of 1901.

In recent years, the conception of a simple focus has been ex tended for many earthquakes to that of a complex origin. The twin-earthquakes of Great Britain originate in two detached foci from 8m. to tom. apart. Calabrian earthquakes belong to several foci, at some times successively in action, at others almost simul taneously. Foci more complex or more extensive than these are in many earthquakes the mere surface manifestations of deep seated movements or bathyseisms. In the Californian earthquake of 1906, the focus certainly reached up to the surface; the depth of the main portion has been variously estimated at from 12 2m. to 67 miles. The Assam earthquake of 1897, with its vast meizoseis mal area and its widely scattered movements, was probably due, as Oldham suggests, to a great bathyseismic displacement. How great may be the depth of these displacements is evident from their seismographic records. It has been variously estimated at from 3o to Boo miles. Even if we regard the latter figure as excessive, we have the conclusions drawn by H. H. Turner from many observations that the majority of these great movements originate at a depth of about 12 5m. and some even as far as 375 miles.

Destructiveness of

Earthquakes.—To most persons, the loss of life and the damage to property are the chief features of a great earthquake. The number of persons killed within a few minutes is sometimes appalling, such as 5o,000 in the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, Ioo,000 in the Messina earthquake of 1908, i8o,000 in the Chinese earthquake of 192o, 200,000 in the Jap anese earthquake of 1703, and, highest of all known, 300,00o in the Indian earthquake of 1737. Figures such as these may be exaggerated, but there can be no mistaking those for the Japanese earthquake of 1923, namely, 99,331 killed, 103,733 wounded and missing, figures which of course include deaths by fire as well as by earthquake. If we reckon the loss by the percentage killed of the total number of inhabitants, the death-rates in the Japanese earthquake were only 2. 7 % in Tokyo and 5.5 % in Yo kohama. Far higher are the rates for some Italian earthquakes, for instance, 41% at Casamicciola in the Ischian earthquake of 1883, about 5o% at Messina in the earthquake of 1908, 71% at Montemurro in the Neapolitan earthquake of 1857, and, in the Marsican earthquake of 1914, 91% at Avezzano and 94% and 9 7 % in two neighbouring villages. In Great Britain, only one life is known to have been lost, an apprentice being killed in Lon don by a falling stone during the earthquake of 1580.We may endeavour to lessen the destructive power of earth quakes in two ways, by forecasting the occurrence of earthquakes, or, and at present more usefully, by a proper choice of site and modes of building. The prevision of earthquakes is as yet in its initial stage. One rather hopeful method depends on the study of the fore-shocks. As the obstacles to slipping are situated in all parts of a fault, it follows that the epicentres of the fore-shocks must mark out roughly the fault-system, or the part of it in which displacement is about to occur. In the case of the Mino Owari earthquake of 1891, the whole region was so outlined within year or two of the great earthquake. Another method has lately been put into practice. From a study of the earthquakes felt at Tokyo from 1914 to 1921, Omori outlined two zones in which earthquakes were then frequent, one covering the Boso peninsula (fig. I), the other the north-west portion of Sagami bay and beyond. Between them lies part of the epicentral area of the earthquake of 1923. Omori inferred that activity would return to the intermediate region when the frequency of earth quakes in the others showed signs of lessening, as it did in the years 192o-2I. Lastly, it has been suggested, that before sliding along a great fault takes place, the crust on either side would show signs of distortion that might be detected by the displace ment of pillars erected along a line at right angles to the fault.

At present, more can be done to counter the destructiveness of earthquakes by the choice of a suitable site and the proper design of buildings. In every earthquake the damage to property is always least on hard rocks ; it is more in houses built on soft ground; greatest of all on recently "made" land, especially on that filling up a marsh or creek. Sites on hard ground should therefore be se lected, while the neighbourhood of unsupported openings, such as the edges of cliffs or river-banks, should be avoided.

In Japan and other earthquake countries, much attention has been paid to the proper form and structure of buildings. In ordi nary works, yielding first shows itself at the base of a pier or wall, and thus such structures as the piers of bridges are made wider and stronger below and tapering upwards. In a so-called earth quake-proof house, the roofs are exceedingly light, chimneys are short and thick, arches are avoided, rafters run from the ridge pole to the floor-sills. The essential point, as was well shown in the Japanese earthquake of 1923, is that the building should be so framed and braced that it will move bodily as one block with its foundations. Thus, in brick buildings crumbled down at once into ruin. Wooden houses withstood the shock fairly well, but were an easy prey to the fires that followed. The modern steel-brick buildings offered a stout resistance to both earthquake and fire, and nearly half of those in Tokyo passed through the trial unharmed.

only work dealing with the history of the science is C. Davison's Founders of Seismology (1927). Among text books may be mentioned F. de Montessus de Ballore's La Science Seismologique (19o7) ; C. G. Knott's Physics of Earthquake Phe nomena (1908) ; G. W. Walker's Modern Seismology (1913) ; and C. Davison's Manual of Seismology (1921) . The most important monographs on earthquakes are those by R. Mallet, The Neapolitan Earthquake of 18S7 (1862) ; C. E. Dutton, "The Charleston Earth quake of Aug. 31, 1886," U.S. Geol. Surv., Ninth Annual Rep., (1889) ; T. Taramelli and G. Mercalli, "I1 terremoto ligure del 23 febbraio 1887," Ann. dell'Uff. Centr. di Meteor. e di Geodin., vol. viii., pt. 4 (Rome, 1888) ; B. Koto, "The cause of the great earthquake in Central Japan, 1891," Journ. Coll. Sci. Imp. Univ. Japan, vol. v. (1893) ; R. D. Oldham, "Report on the great earthquake of June 12, 1897," India Geol. Surv. Rep., vol. xxxix. (1899) ; R. S. Tarr and L. Martin, "The earthquakes of Yakutat Bay, Alaska, in September 1899," U.S. Geol. Surv. Prof. Paper No. 69, (1912) • A. C. Lawson (ed.), The Californian Earthquake of April 18, 1906 (Washington, Carnegie Institution, 2 vols., 1908-1o) ; and M. Baratta, La Catastrofe Sismica Calabro-Messine, 28 Dicembre 1908 (Soc. Geogr. Ital., Rome, 191o) . Descriptions of various earthquakes are given by C. Lyell, Principles of Geology, 12th ed., (1875) ; C. Davison, A Study of Recent Earthquakes (1905) • and F. de Montessus de Ballore, La Geologic Sismologique (1924) . Many regional monographs have been published, including a long series by A. Perrey (1844-66) , and a later series by F. de Montessus de Ballore, culminating in his Geographie Seismologique (1906) . More detailed works are those by M. Baratta, I Terremoti d'Italia (19oi) , and C. Davison, A History of British Earthquakes (1924) . The most important world-catalogues of earth quakes are those compiled by R. Mallet, "Catalogue of recorded earth quakes" (16o6 B.c.-A.D. 1842) , Brit. Ass. Rep., 1852, 1853 and 1854; and J. Milne, "A catalogue of destructive earthquakes" (A.D. 1-1899), Brit. Ass. Rep., 1911. Among the chief periodical works relating to seismology are the reports of the Seismological Committee of the British Association (from 1896), the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, the Bollettino of the Italian Seismological Society and the Bulletin of the Earthquake Research Institute (Tokyo) .

(C. D.) In late April and early May 1928 the modern city of Corinth was almost completely destroyed by repeated earthquake shocks of great intensity and thousands of citizens were rendered home less. The country districts were also badly affected and in Bul garia many towns and cities were shaken to their foundations. Smyrna and other cities in Asia Minor were very badly damaged.

A severe earthquake occurred in Burma (193o), killing several hundred and virtually obliterating Pegu. This was immediately followed by a shock of equal force in Persia. Another at Managua, Nicaragua (1931) brought death to hundreds and gave the United States marines a chance to employ themselves humanely in the succour of the thousands left homeless. In January 1934 a violent tremor shook all of India, destroying about 6,000 lives. (X.)