Ecclesiasticus

ECCLESIASTICUS (abbreviated to Ecclus.), an alterna tive title of the apocryphal book otherwise called "The Wisdom of Jesus the son of Sirach." The Latin word ecclesiasticus means "churchly," and might be used of any book which was read in church or received ecclesiastical sanction. The name of the book appears in the authorities in a variety of forms. The writ er's full name is given in 1. 27 (Heb. text) as "Simeon the son of Jeshua (i.e., Jesus) the son of Eleazar the son of Sira." In the Greek text this name appears as "Jesus son of Sirach Elea zar of Jerusalem." The name is shortened sometimes to Ben Sira in Hebrew, Bar Sira in Aramaic, and sometimes to Sirach. The wotk is variously described as the Words (Heb. text), the Book (Talmud), the Proverbs (Jerome), or the Wisdom of the son of Sira (or Sirach).

Of the date of the book we have no certain indication. It was translated by a person who says that he "came into Egypt in the 38th year of Euergetes the king" (Ptolemy VII.), i.e., in 132 B.c., and that he executed the work some time later. The translator believed that the writer of the original was his own grandfather (or ancestor, iraoriros). Arguments for a pre-Mac cabean date may be derived (a) from the fact that the book contains apparently no reference to the Maccabean struggles, (b) from the eulogy of the priestly house of Zadok which fell into disrepute during these wars for independence.

In the Jewish Church Ecclesiasticus hovered on the border of the canon. The book contains much which attracted and also much which repelled Jewish feeling, and it appears that it was necessary to pronounce against its canonicity. In the Talmud (Sanhedrin Ioo b) Rabbi Joseph says that it is forbidden to read (i.e., in the synagogue) the book of Ben Sira. In the Chris tian Church it was largely used by Clement of Alexandria (c. A.D. 200) and by St. Augustine. Jerome (c. A.D. 390-400) writes: "Let the Church read these two volumes (Wisdom of Solomon and Ecclesiasticus) for the instruction of the people, not for establishing the authority of the dogmas of the Church" (Prae fatio in libros Salomonis). In the Vulgate Ecclesiasticus immedi ately precedes Isaiah. The council of Trent declared this book and the rest of the books reckoned in the Thirty-nine Articles as apocryphal to be canonical.

The text of the book raises intricate problems which are still far from solution. The original Hebrew (rediscovered in frag ments and published between 1896 and 1900) has come down to us in a mutilated and corrupt form. There are marginal readings which show that two different recensions existed once in Hebrew. The Greek version exists in two forms—(a) that preserved in cod. B and in the other uncial mss., (b) that pre served in the cursive codex 248 (Holmes and Parsons). Owing to the mutilation of the Hebrew the Greek version retains its place as the chief authority for the text.

The restoration of a satisfactory text is beyond our hopes, for we cannot doubt that the translator amplified and paraphrased the text before him. It is probable that at least one considerable omission must be laid to his charge, for the hymn preserved in the Hebrew text after ch. li. 12 is almost certainly original. Ancient translators allowed themselves much liberty in their work, and Ecclesiasticus had no reputation for canonicity in the 2nd century B.C. to serve as a protection for its text.

The uncertainty of the text has affected both English versions unfavourably. The A.V., following the corrupt cursives, is often wrong. The R.V., on the other hand, in following the uncial mss. sometimes departs from the Hebrew, while the A.V. with the cursives agrees with it. Thus the R.V. omits the whole of iii. 19, which the A.V. retains, but for the clause, "Mysteries are revealed unto the meek," the A.V. has the support of the Hebrew. Sometimes both versions go astray in places in which the Hebrew text recommends itself as original by its vigour; e.g., in vii. 26, where the Hebrew is: Hast thou a wife? abominate her not. Hast thou a hated wife? trust not in her.

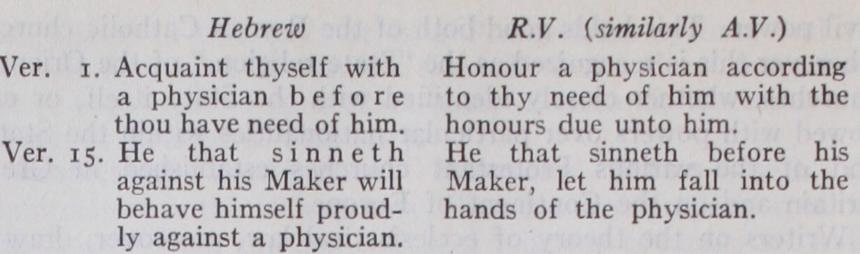

Again in ch. xxxviii. the Hebrew text shows its superiority over both English versions.

In the second instance, while the Hebrew says that the man who rebels against his Heavenly Benefactor will a fortiori rebel against a human benefactor, the Greek text gives a cynical turn to the verse, "Let the man who rebels against his true benefactor be punished through the tender mercies of a quack." The He brew text is superior also in xliv. 1: "Let me now praise favoured men;" i.e., men in whom God's grace was shown. The Greek text of v. i "famous men," is nothing but a loose paraphrase.

In character Ecclesiasticus resembles the book of Proverbs. It consists mainly of maxims, moral, utilitarian and secular. Occasionally the author attacks prevalent religious doctrines, e.g., the denial of free-will (xv. or the assertion of God's indifference towards men's actions (xxxv. 12-19). Occasionally he touches the highest themes, and speaks of the nature of God: "He is All" (xliii. 27) ; "He is One from everlasting" (xlii. 21, Heb. text) ; "The mercy of the Lord is upon all flesh" (xviii. 13) . The book contains several passages of force and beauty; e.g., ch. ii. (how to fear the Lord) ; xv. 11-20 (on free-will) ; xxiv. 1-22 (the song of wisdom) ; xlii. 15-25 (praise of the works of the Lord) ; xliv. 1-15 (the well known praise of famous men). Many sayings scattered throughout the book show depth of insight or practical shrewdness. A few examples may be cited. "Call no man blessed before his death" (xi. 28) ; "He that toucheth pitch shall be defiled" (xiii. I) ; "God hath not given any man license to sin" (xv. 2o) ; "Man cherisheth anger against man; and doth he seek healing from the Lord?" (xxviii. 3) ; "All things are double one against another: and He hath made nothing imperfect" (xlii. 24, the motto of Butler's Analogy) ; "Work your work be fore the time cometh, and in His time He will give you your re ward" (li. 3o). It cannot be said, however, that Ben Sira preaches a hopeful religion. Though he prays, "Renew Thy signs, and re peat Thy wonders. . . . Fill Sion with Thy majesty and Thy Temple with Thy glory" (xxxvi. 6, 14 [19], Heb. text), he does not look for a Messiah. Of the resurrection of the dead or of the immortality of the soul there is no word. In his maxims of life he shows a frigid and narrow mind. He is a pessimist as regards women: "From a woman was the beginning of sin; and because of her we all die" (xxv. 24). He does not believe in home-spun wisdom : "How shall he become wise that holdeth the plough?" (xxxviii. 25). Artificers are not expected to pray like the wise man: "In the handywork of their craft is their prayer'' (v. 34). Merchants are expected to cheat: "Sin will thrust itself in between buying and selling" (xxvii. 2).