Echinoderma

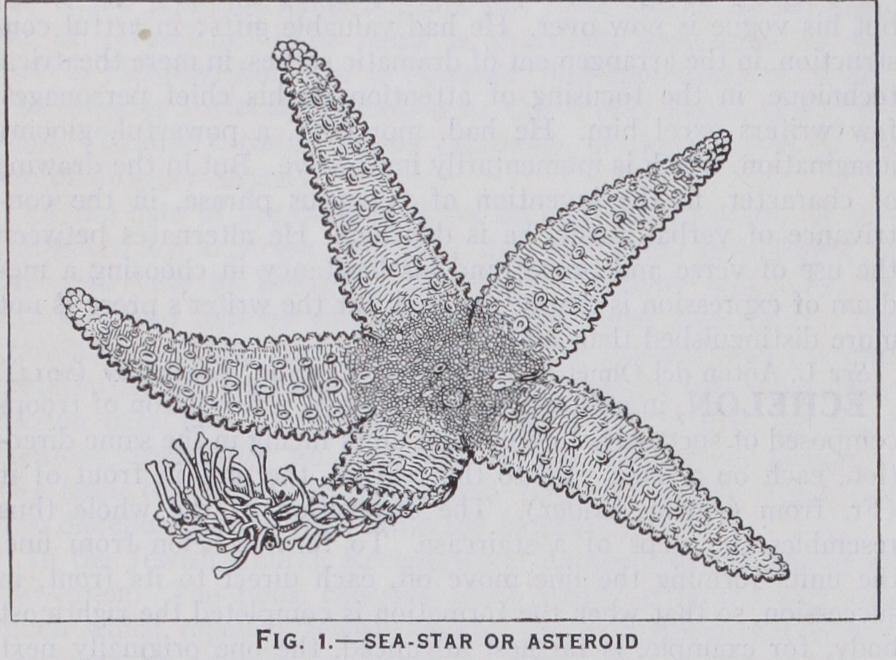

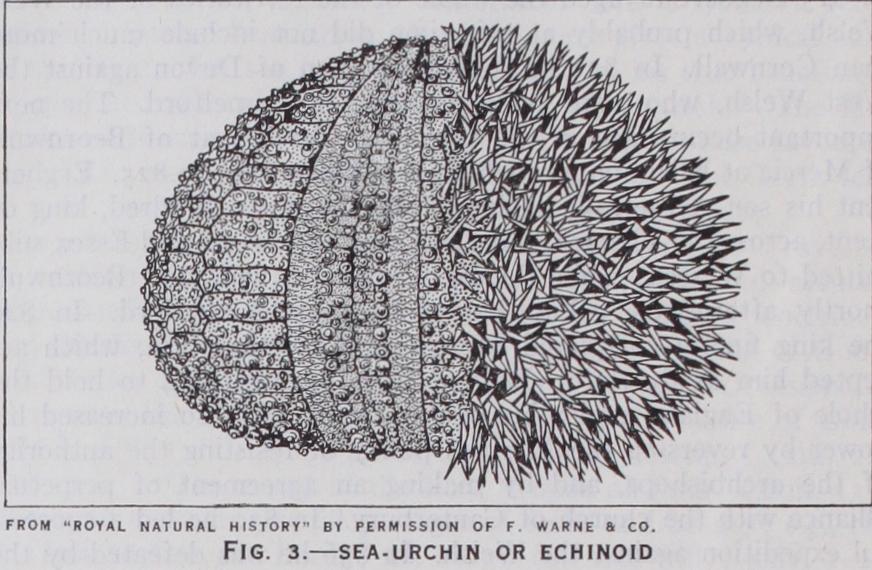

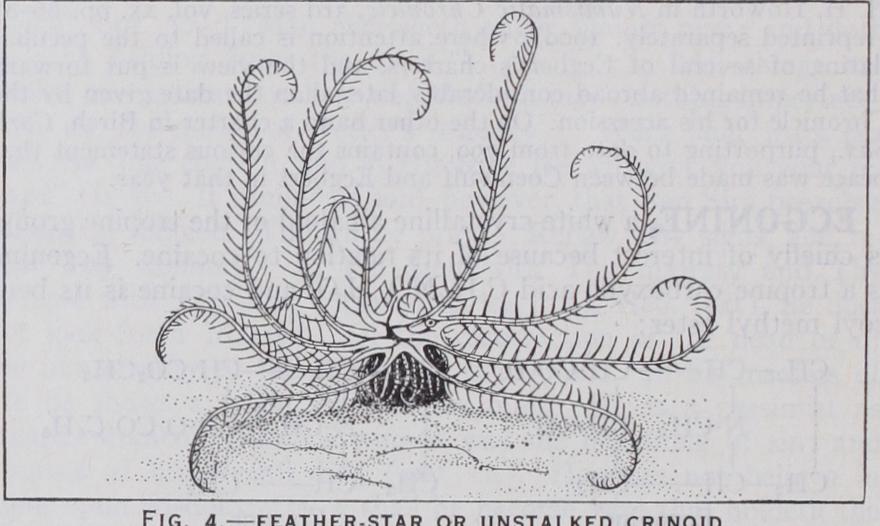

ECHINODERMA (Echinoderms), a group of animals that live in the sea and constitute one of the great branches (phyla) of the animal kingdom. Familiar examples are the sea-urchin (Echinoid), the sea-star or starfish (Asteroid) and the brittle star (Ophiuroid). Less familiar are the feather-star and sea-lily (unstalked and stalked Crinoid), and the sea-cucumber (Holo thurian) (figs. 1-5). These forms represent the five classes into which the Echinoderma now living are usually divided. In the older periods of the world's history there were other classes, none of which have survived.

The recent forms are of such diverse appearance, and for the most part so unfamiliar, that there is no vernacular English name for the branch. "Echinoderma" is a Greek word and means "prickle-skinned" ("animals" being understood). The Greeks gave the name "Echinus" to two animals of very different nature, but both protected by a coat of prickles : one the hedgehog or urchin of the land ; the other the sea-urchin, which the French call oursin. Both urchin and oursin are connected with the French herisser, to bristle. The name Echinus has been continued in use for a kind of sea-urchin. The name "Echinodermata," often applied to the whole branch, means "sea-urchin skins," and was invented in 1734 by J. T. Klein to denote only the empty shells or tests of sea-urchins.

Diverse though recent echinoderms are, all possess certain characters, some of which they hold in common with other groups of animals, while others are distinctive of the branch. The com mon characters may be mentioned briefly. The substance of an echinoderm is built of many cells ; the animals are multicellular (Metazoa, as opposed to Protozoa). An echinoderm differs from such animals as sea-anemones and jelly-fish, which are little more than sacs (Coelentera=hollow guts), in having the inside of the sac divided into a gut or digestive tube and a body-cavity or coelom (=hollow) ; in this it resembles molluscs, flat-worms, arthropods and vertebrates : such animals are called Coelomata. The fundamental plan of an echinoderm, as in all Coelomata, is bilateral, and any appearance of radial symmetry is secondary.

Radial Arrangement.

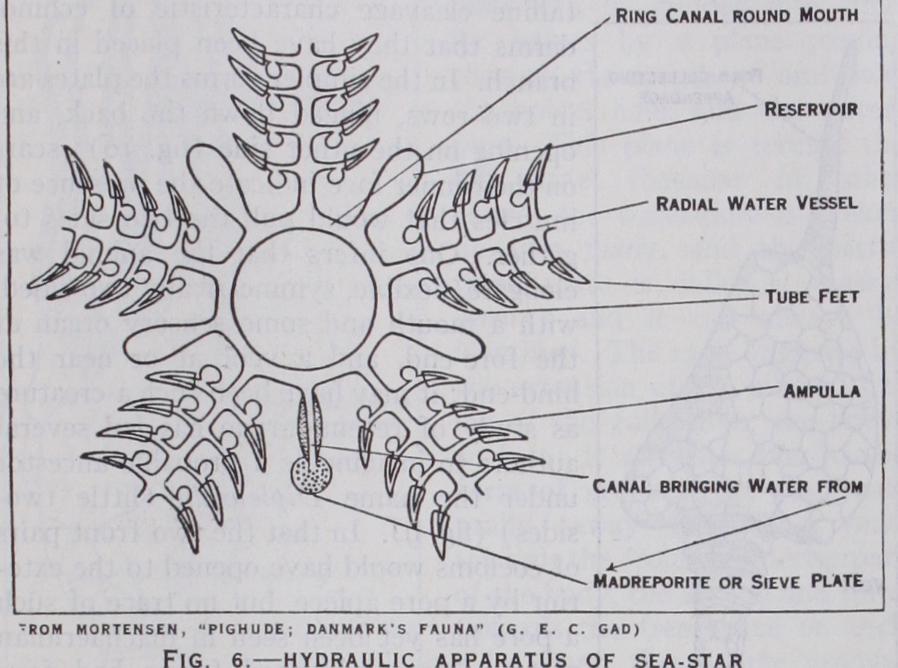

Recent Echinoderma are distinguished from the other Coelomata by the following characters :—Nearly all show a division of some of the bodily organs into five rays. The rays may fork, may increase, or may be partly suppressed; but the number five governs the plan, though it is not really primitive. The middle line of each ray is termed a radius ; a line drawn midway between two adjoining radii is termed an interradius : thus the body-surface may be mapped into five radial areas alternating with five interradial areas. In recent echinoderms the organs that show the radial arrangement most clearly are numerous sacs, canals and tubes which carry water through the body and constitute a hydraulic apparatus (water vascular system). In its most typical form (fig. 6) this consists of a ring-canal round the mouth, indirectly connected with the water outside, and sending a canal down each of the radii. From each side of this radial water-vessel small branches are given off, and their ends project from the surface of the animal as closed tubes with muscular walls; since in the sea-urchin and sea-star these tubes end in suckers and aid locomotion, they are called tube-feet or podia (fig. I). The podia, as they stand up on each side of the radial canal, look like flowers bordering a garden-walk (Lat., ambulacrum) ; hence that radial area of the test is called an ambulacrum, and the interracial areas are called inter ambulacra.

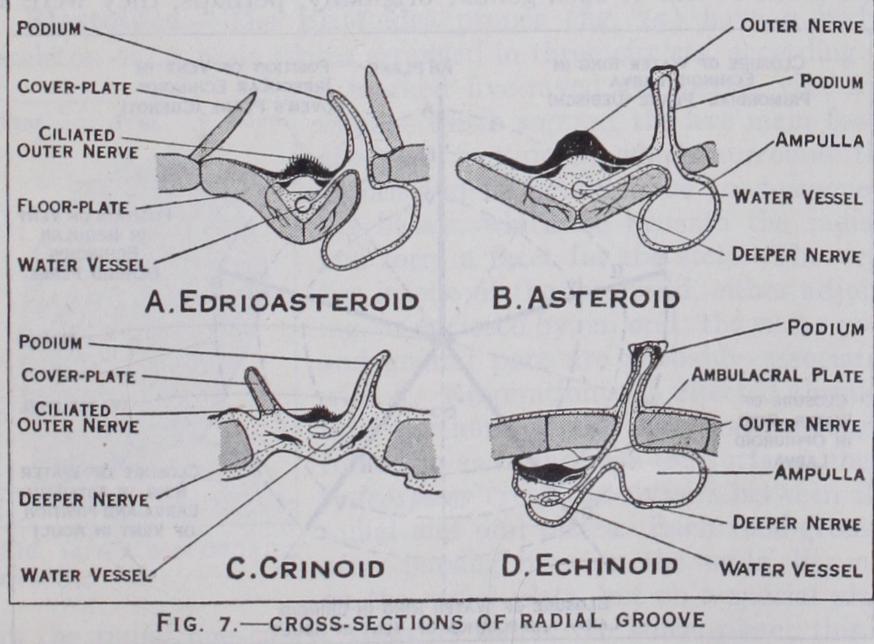

In the older and more primitive classes of Echinoderma, the hydraulic ambulacral system does not subserve locomotion, but only sensation and respiration. The five-rayed structure did not originate in this system, but was due to the extension from the mouth of five grooves lined with minute lashes (cilia), which by constant whipping drive a stream of water with food-particles towards the mouth. The food-collecting area was increased by the elongation or branching of the grooves, as in crinoids and sea stars ; and the water-vessels followed the food-grooves. In cri noids and sea-stars the food-grooves are open and in use; but in brittle-stars, sea-urchins, and holothurians they have become closed over, while the ambulacral system continues to send out its podia (fig. 7) .

Spicular Structure of Skin.

The name Echinoderma ex presses one of the chief characters of the branch. Prickles, it is true, are not so well developed in the other classes as they are in sea-urchins, though they are to be found more or less frequently in most of them. The essential feature is the presence in the deeper layers of the skin of minute spicules of crystalline car bonate of lime (calcite), which usually grow together into plates, or small bones, or prickles, all so interpenetrated with the con necting fibres of the skin that they constitute a beam-and-rafter work (fig. 8). Under the microscope a thin section of this looks like a net. Wherever the mid-layer or mesoderm occurs in the body, and not only in the skin, its cells have this power of de positing lime ; they can also re-absorb it and redeposit it, so that the shape and structure of the skeleton change as the animal grows. In all these respects the skeletal tissue of Echinoderma is paralleled only by the bone of Vertebrata; but it differs from bone in chemical composition, in the formation of the spicules within the cells and not outside them, and in the retention of a crystalline character so that each plate acts as an individual crystal. By the cleaved surface characteristic of calcite and the net-like appearance, even minute fragments of echinoderm skele ton embedded in the rocks can be distinguished from the remains of molluscs, corals, arthropods and other animals.

Other Common Characters.

The f ollowing characters of less obvious nature are also common to all recent echinoderms:— The egg develops first into an elongate, two-sided larva (figs. 9 and 21), with an untwisted gut, and with the body-cavity essen tially arising as three pairs of pouches (coeloms) ; all or part of this is somewhat abruptly changed into a radial creature with coiled gut. This characteristic metamorphosis is described later. The nervous systems are three : (I) the outer oral sensory system, chiefly composed of a ring round the mouth, and radial nerves, lying outside the water-vessels, and derived from the epithelium; (2) the deeper oral motor system, lying just below the former, supplying the muscles in the oral side of the body-wall, and derived from the mesoderm; (3) the apical motor system, most pronounced in crinoids; its centre is where the stem originates, and its cords pass down the stem and the rays to work their muscles; it is in all classes except holothurians, and is derived from endothelium. The blood system consists of a number of spaces rather than definite vessels, without heart or regular circulation ; its contents differ from the general fluid of the body cavity only in containing more albumen. In all the internal fluids float various bodies : some are red with haemoglobin (like human blood-corpuscles) and aid respiration; others are white, wander ing, amoeba-like cells, which serve many purposes, some eating the various waste-products and then squeezing their way to the exterior, for there is no definite excretory system.

Relationships.

The Echinoderma, as we have seen, differ from other radial animals, but agree with many other branches, in the separation of a body-cavity (coelom) from the primitive hollow, which persists as the gut. The various branches of the Coelomata may have sprung independently from the Coelentera, and if there was any connection between them it must have been through forms whose existence we can only infer from a study of the oldest fossils and of the earliest stages in the life-history of their living descendants. Thus we find the mode of origin of the coelom and its early division into three pairs of sacs paralleled only in that great branch of the Coelomata which includes all animals with a backbone or with its cartilaginous precursor termed "notochord." The lower Chordata (as the branch is named) comprise the lancelet (.imphioxus), the sea-squirts or ascidians, and some less-known, often worm-shaped creatures named Enteropneusta. All Chordata, except sea-squirts, show traces of this triple division of the coelom; and the growth of its middle division into lobes and tentacles is seen also in some Enteropneusta. The larva of one of the Enteropneusta (Balano glossus) was originally described as an independent animal (Tornaria) and supposed to be related to the Echinoderm larval forms—the presence of a water pore accentuates the outer simi larity. The mouth of the developing echinoderm, when it shifts from the original median position, invariably moves to the left not to the right ; in the lancelet the mouth appears first on the left side. The central nervous system of Chordata, like the outer oral nervous system of Echinoderma, is derived from the outer epidermis and sinks below the surface in the same manner; this indicates that the ancestral forms responded to certain outer stim uli by a similar mechanism. The resemblances and differences between echinodermal and vertebrate skeletal tissue have already been emphasized. All these facts suggest that the Echinoderma and the Chordata were derived from a common ancestor, differing from the ancestors of other Coelomata, but itself not yet either an echinoderm or a chordate.

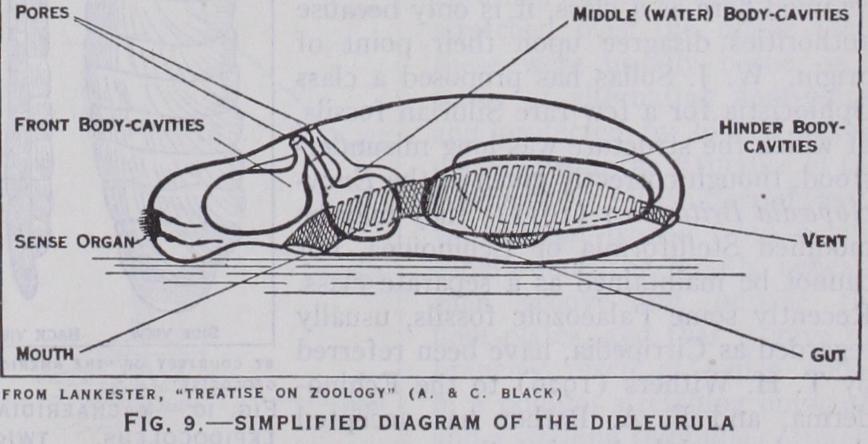

The five classes into which, as said at the outset, Echino derma now living are usually divided, are not of equal value, for the Asteroidea and Ophiuroidea diverged in a comparatively late geological period, so that the differences between them are not so profound as those that distinguish the other classes; the difficulty is met by merging them in a super-class, Stelliformia. In early Palaeozoic times there existed other classes, all of which became extinct before the Mesozoic era began. Most of those creatures resembled the crinoids in being attached to the sea-floor and in feeding on minute organisms, which they swept along ciliated grooves into their usually upturned mouths. They have therefore been grouped with the crinoids as Pelmatozoa (stalk-animals), while the remaining classes, which are free-moving and generally feed with down-turned mouth on larger organisms, have been op posed to them under the name Eleutherozoa (free animals). These names conveniently connote definite facts of structure and habit, but do not imply any closer relationship between the classes included under them. The classification here adopted embodies a few recent advances. Certain Pelmatozoa that, in editions of the Encyclopedia Brit annica after 1900, have been placed under Cystoidea as an order Carpoidea are now distinguished as a class. On the other hand the Blastoidea, though numerous and rather sharply defined, are a relatively late off shoot from the Cystoidea, and if they are retained here as a class, it is only because authorities disagree upon their point of origin. W. J. Sollas has proposed a class Ophiocistia for a few rare Silurian fossils, of which the structure was long misunder stood, though correctly given in the Ency clopedia Britannica (1911) ; they may be modified Stelliformia or Echinoidea, but cannot be maintained as a separate class. Recently some Palaeozoic fossils, usually regarded as Cirripedia, have been referred by T. H. Withers (1926) to the Echino derma, and F. A. Bather has accepted that view, while keeping them apart as a rub-branch, Machaeridia. The larger divisions of the Echinoderma here accepted may be tabulated, without implication as to their mutual affinities, thus : With no trace of Radial structure t Machaeridia tCarpoidea With more or less Radial structure f Cystoidea Pelmatozoa f Blastoidea Crinoidea f Edrioasteroidea Machaeridia.—Of the Machaeridia only the skeleton is known, and it is mainly because its plates have shown the crys talline cleavage characteristic of echino derms that they have been placed in this branch. In the simpler forms the plates are in two rows, hinged down the back, and opening on the other side (fig. Io) ; scars on their inner face indicate the presence of muscles that would pull the two sides to gether. One infers that the animal was elongate, flexible, symmetrically two-sided, with a mouth and some sensory organ at the fore-end, and a vent at or near the hind-end ; it may have been such a creature as study of recent larvae has led several authors to imagine as a probable ancestor under the name Dipleurula (little two sides) (fig. 9). In that the two front pairs of coeloms would have opened to the exte rior by a pore apiece, but no trace of such a pore has yet been seen in machaeridian plates. More advanced forms had four rows of plates, two on each side. At one end a plate was often modified in a way that suggests temporary fixation.

Carpoidea.—All Carpoidea bear traces of a stem by which the body was attached to some object on or near the sea-floor (fig. I I ) . In most the skeleton shows some two sided symmetry, if only in a part of the stem; this may have originated in the sym metry of the Dipleurula, but its gradual in crease in various series of the class is due to adaptation. Nearly all Carpoidea are flattened in a plane parallel to the sea-floor, and either the whole body-wall is flexible or one side remains flexible, so that it could expand and contract as the animal drew in or expelled water for food or aeration. The positions of intake and vent relative to the stem and to each other vary according to the particular habitat and mode of life of each genus; originally, perhaps, they were at two-sided symmetry, but in them we see the rise of radial sym metry. Study of this enables one to draw a plan by which the symmetries in other classes can be compared (fig. i a). Normally the cystoids are attached to the sea-floor by one pole of the body and take in food through a mouth at the opposite, upper pole.

Near the mouth is a water-pore, and close to it, but further from the mouth, is a genital pore ; the vent is usually in the same line, at the side of the body. Thus the body can be divided into simi lar halves by a plane passing through the mouth or oral pole, the apical hole, and the water pore. This plane is termed the M plane (because in other classes the water-pore is broken up into many, and the perfo rated plate is called a madre porite) and it can always be identified. The rays originate by the extension of the ciliated lin ing of the gullet over the body surface ; it stretches out in the form of grooves, the first, nat urally, away from the vent, towards the front or anterior part of the body, the second and third towards the free space on each side ; later, these three grooves become five by the forking of the right and left grooves. The food-collecting surface was usu ally increased by the extension of the grooves on little jointed appendages (brachioles), which did not contain prolongations of the body-cavity or of the generative system (fig. 13) . The water-system may have sent branches through the mouth-opening along the food-grooves, but did not subserve locomotion. Aeration of the body-fluids was effected through thinner portions of the test, and according to the structure of these the Cystoidea may be grouped in two sub classes :—(i) Rhombifera or Dichoporita, in which the breathing organs are folds of the test-wall, crossing the sutures of the plates (fig. 13) ; (2) Diploporita, in which the breathing organs are canals of U -shape within the test wall and not crossing the sutures (fig. 14). There are other differences between these sub classes.

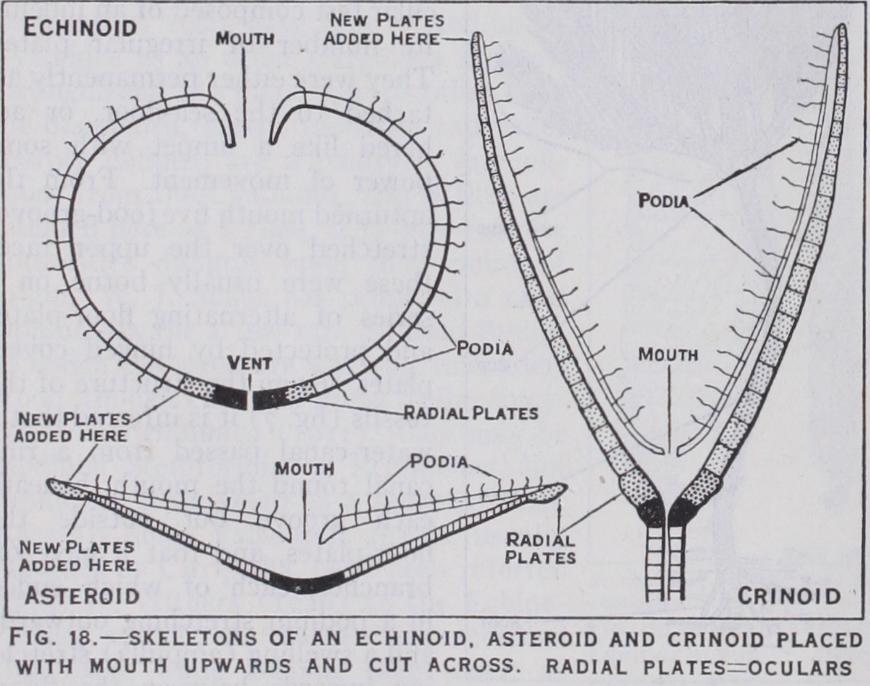

Blastoidea.—The Blastoidea proper (fig. 15) have a skeleton of 13 main plates arranged in three circlets, according to a marked five-rayed symmetry, viz., five radials, which support the five main grooves; five orals, which surround the mouth and lie between the food-grooves; the basals, which lie beneath the radials and form a facet for the stem. The vent lies in one of the interradii, either ing, or enclosed by, an oral ; the water-pore and genital pore are probably associated with it. Respiration was effected through thin portions of the test wall, strongly folded so as to increase the surface; these hydrospires cross the sutures between the radial and oral plates. Each food-groove, after passing between the orals, lies not on the radial plate, but on a special plate in the radial line called, from its shape, the lancet-plate; this is bordered by small side-plates, to which brachioles are attached. Crinoidea.—The body of the Crinoidea (fig. 16) is normally borne on a stem, has the food-collecting system upwards, and the vent in the M plane at the side or raised away from the intake on a sort of chimney (anal tube). The food-grooves are extended on five arms or brachia, which are not, like brachioles, mere ap pendages to the test, but actual outgrowths of the body (fig. 7) containing throughout extensions of the body-cavities, the genera tive organs, and the apical nervous system, as well as bearing the usual water-vessels with their side-branches and podia, and nerves from the two oral systems. The arms, which are built of suc cessive plates (brachia's), may fork or branch repeatedly, and the smaller branches may become ar ranged along the sides of the larger, forming pinnules. O. Jaekel, however, holds that the pinnules of certain forms repre sent the brachioles of cystids. The body with its arms is termed the crown; that portion of it be low the free part of the arms is the dorsal cup; the covering or lid of the cup, above the free part of the arms, is the tegmen. In the simpler crinoids the cup consists of only two or three circlets of plates : the five radials, from which spring the arms ; the (primitively) five basals, beneath the radials and alternating with them ; and often the (primitively) five infrabasals, beneath and al ternating with the basals. Infra basals are wanting in some groups (monocyclic), present in others (dicyclic), but maybe overgrown by the basals or may atrophy in the adult (cryptodicyclic). The cup may be enlarged by the incorporation of the lower parts of the arms, between which other plates (interbrachials) often arise ; to make room for the vent, or to support it, special anal plates may be added. The gut, as viewed from the oral sur face, is coiled in a clockwise direction (solar).

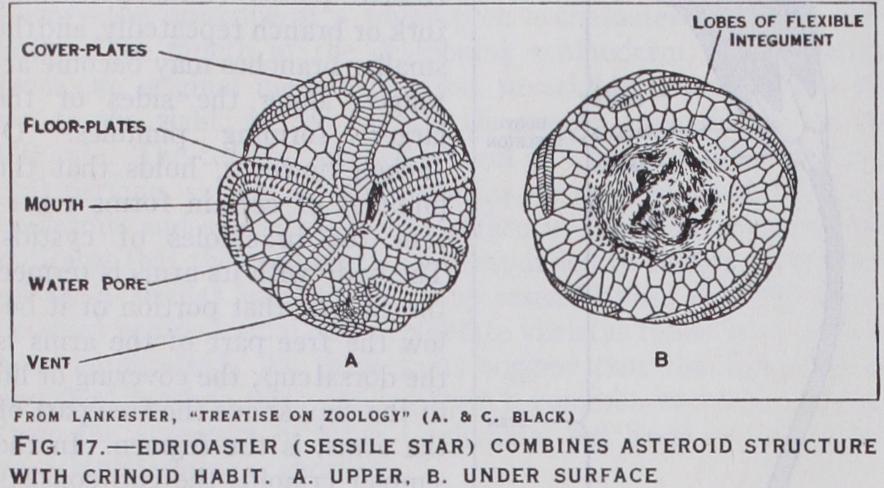

Edrioasteroidea.—The Edri oasteroidea (fig. 17) had a cir cular test composed of an indefin ite number of irregular plates. They were either permanently at tached to the sea-floor, or ad hered like a limpet with some power of movement. From the upturned mouth five food-grooves stretched over the upper face ; these were usually borne on a series of alternating floor-plates and protected by hinged cover plates. From the structure of the fossils (fig. 7) it is inferred that a water-canal passed from a ring canal round the mouth, beneath each groove but outside the floor-plates, and that it gave off branches, each of which ended in a podium stretching outwards and a swelling (ampulla) stretch ing inwards between the floor plates to form a reservoir ; no other Pelmatozoa show such a structure. There were no brach ioles. The gut seems to have had a solar coil; its vent and madre porite lay on the same side as the mouth. In some genera the depth of the food-grooves impressed a five-rayed symmetry on the generative organs.

Stelliformia.

The Stelliformia (sea-stars, brittle-stars, et al.) live as a rule with the mouth downwards ; from it radiate five ciliated grooves with a superficial nervous tract, as in Pelma tozoa; the structure of these grooves and of their associated water system is as just described for Edrioasteroidea (fig. 7). The creature indeed resembles an Edrioaster turned upside-down, but differs in that both vent and water-pore are on the apical face, which is now uppermost ; they are, moreover, no longer both in the same interradius : while the madreporite, as shown in fig. 12, still marks interradius C/D of the M plane, the vent has moved into B/C. In correlation with the overturn, food-collect ing by ciliated grooves has given place to active search for and ingestion of animal food, alive or dead, in larger portions; this again has led to modification of plates round the mouth into jaws, and to prolongation of the ambulacra on radial extensions of the body, giving the animal first the star shape (fig. i ), then the form of a disc with five arms (fig. 2). The terminal plate of each ray is separated from the apical pole by a stretch of plated integu ment; the grooves never bend round on to the upper surface. Since each terminal bears an organ sensitive to light, it is also called an ocular. According as they move by crawling or wrig gling recent Stelliformia fall into two classes : Asteroidea and Ophiuroidea.

In the Asteroidea (fig. r) the ambulacral grooves remain open and the podia change into tube-feet, each with a sucker at the end, by which the sea-star clings to objects and pulls itself along; a podium can be withdrawn into the groove by its muscles, when its fluid contents pass into the ampulla; contraction of the am pulla squeezes the fluid again into the podium, swelling it out for use. The arms are not, as a rule, sharply distinguished from the body, and they contain both genital glands and blind extensions of the digestive system (caeca). The body-fluids are aerated through thin-walled outgrowths of the body-cavity (papulae) which pass between the plates of the upper surface. Podia and papulae are protected by thorns or spikes, which are sometimes clumped (paxillae), sometimes branched and bearing a mem brane, sometimes modified into small grasping organs (pedi cellariae). Many sea-stars have more than five arms, but the arms never fork.

The Ophiuroidea (the name means snake-tail forms) owe their name to the long, thin, flexible arms, which spring abruptly from the central disc (fig. 2). The arm-groove is covered, the podia cease to act as tube-feet, the floor-plates are thickened and joined by pairs into solid bones shaped like vertebrae and connected by strong muscles. No room is left in such arms for genital glands or digestive caeca. The outer plates of both disc and arms are broad shields, without interspaces for papulae. Sometimes aera tion is through clefts at the bases of the arms. The thorns remain small and usually of simple struc ture. No ophiuroid has more than five arms, but in one order (basket-fish) the arms may fork several times and the animals cling to branched corals.

Echinoidea.

The Echinoidea (sea-urchins, figs. 3, 19) also live mouth downwards. A simple regular echinoid may be com pared to an asteroid in which the vent is at the apical pole, and the grooves have grown round on to that face of the test (fig. 18), so that their terminal ocular plates encircle the vent and are sep arated from it only by five other plates of rather larger size, each pierced by an opening for the extrusion of the genital prod ucts (hence called genital plates), and one also pierced by numer ous water-pores (madreporite). The test having become rigid as well as globular, the soft structures of the grooves have sunk be neath it, and the podia emerge through the plates (fig. 7) . The absence of papulae from the close-built test throws more res piratory work on the podia, and to aid this the canal of each is divided, and cilia sweep a current up one half and down the other; thus the pores for the podia are double like the diplopores of cystoids. The plates through which the podia pass are called ambulacrals; new evidence suggests that they correspond to the floor-plates of Asteroidea and Edrioasteroidea, not to the cover plates or to any structure in Crinoidea, Cystoidea or Blastoidea. The genital glands are much branched, and here remain inter radial.In a regular echinoid (fig. 3) the madreporite and vertical axis mark the M plane; the vent is not precisely at the apical pole, but is shifted in the direction of radius B (fig. 12). According to S. Loven, the plates of the five interradii are symmetrical with regard to the plane B-D/E, which therefore is called the echinoid plane. In a large number of later sea-urchins the vent moves towards the under-side of the test, whence such forms are called irregular echinoids (fig. 19). In most the vent passes along inter radius B/A, while the mouth moves in the other direction along radius D ; the plane thus marked is known as Loven's plane. In such urchins the groove D is termed anterior, and, with the adja cent C and E, forms the trivium, while grooves A and B form the bivium. These are not the same rays as form the so-called trivium and bivium in the other classes. The change to irregular is connected with a change in the mode of feeding. Regular echinoids have five teeth, interradially placed and held in a frame of 20 pieces, which Aristotle compared to a ship's lantern. In those later forms that take to feeding on ooze or minute food, these structures are gradually lost.

It is in the urchins that the spikes or prickles of the skin are most highly developed. They are generally called spines (Lat. spina, a thorn), but as "spine" has a different meaning, in English and anatomy, the term "radiole" is preferable. They are attached to round-headed tubercles on the test by a ball-and-socket joint, and are moved by muscles. Primarily radioles serve for protec tion, but the larger radioles may be used like stilts for locomotion or for digging. Some radioles are minute, clothed with cilia, and arranged in narrow bands (fascioles), which are supposed to sweep currents of water for aeration or sanitation. Pedicellariae are always present, and are of five different types. Holothuroidea.—The Holothuroidea (holothurians, sea-cu cumbers) resemble the Echinoidea in that the outer skin covers the grooves and is pierced by the podia. But, whereas a sea urchin moves sideways in any direction, a normal holothurian (fig. 5) moves only in the direction of its mouth, with the body stretched along the sea-floor, and the vent at the other end. The surface turned to the sea-floor is always the same, and is usually flattened; down its middle line is one of the radii (A), with radius B to its right and E to its left (fig. i 2) , the podia of these radii serve as sucking feet, but those of radii C and D, on the upper surface, are used only for feeling and aeration. Near the front or mouth end of the middle upper interradius C/D opens the duct from the single genital gland, while the water-pore opens just in front of it in the larva and in the adult too in some species; in others the pore closes and the water-system obtains its fluid from the body-cavity through openings in the stone-canal. There is no apical system of plates, and no terminal plate or special tentacle at the end of each ray. In these respects and in the symmetry of the rays the holothurians depart from other Eleutherozoa and approach such early Pelmatozoa as Edrioaster.

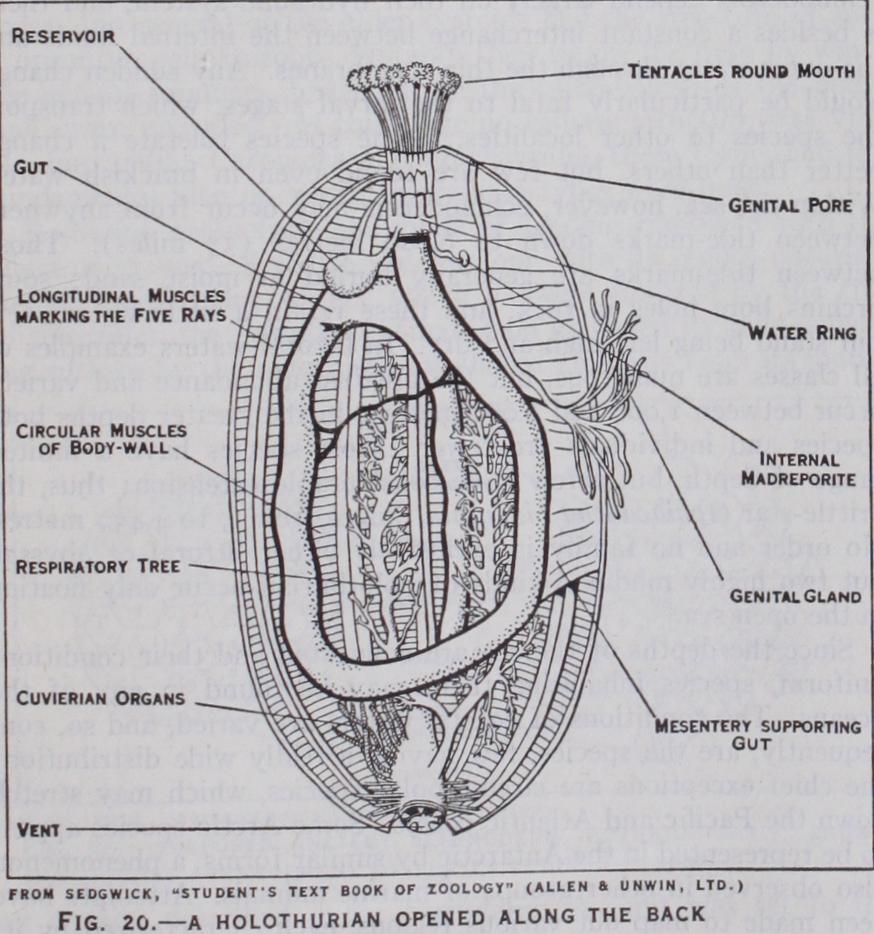

The following special features are found in most holothurians (fig. 2o). The mouth is surrounded by the ten front which have become prominent tentacles. Outside these is a rim, which can close over both mouth and tentacles. The body-wall has two sets of muscles : a transverse, circular layer, which, on contraction, compresses the contained fluids and thus elongates the body; five pairs of longitudinal muscles, alongside the radii, which on con traction shorten the body (it is hard to hold a holothurian). The gut passes from the mouth, below interradius C/D to the hinder end of the body, then forwards along interradius D/E, then downwards along A/B to the vent ; thus it has a solar coil as in crinoids and echinoids. Most holothurians suck in water through the vent for aeration ; to accommodate this the rectum is enlarged and, in numerous species, gives off two many-branched tubes with blind ends, termed the respiratory trees. In most holothurians the skeleton is greatly reduced. Round the gullet is usually a ring of five radial and five interradial pieces, which may correspond to the mouth-frame of echinoids. There are no regular plates in the body-wall, but throughout the skin and the connective tissue are scattered minute spicules, which have different shapes character istic of the various genera and species; in one or two genera some of these are enlarged to form irregular plates, and in one or two they are absent altogether.

In most echinoderms the sexes are separate, but not distin guished by any external character. The genital products are dis charged into the water, where the eggs are fertilized by the sperm. The egg then divides into a number of cells, which form a hollow ball. One end of this grows inwards, and the result is an open mouthed sac with a double wall. From the walls cells migrate into the space between, forming a middle layer. This stage cor responds to the structure of the jelly-fish, etc. (Coelentera). The body-cavity arises from the hollow of the sac as a single pouch growing out into the loose middle layer. By repeated division of this pouch arise the three pairs of coeloms shown in the diagram of the dipleurula (fig. 9). Meanwhile the sac lengthens and is flattened on one side, towards which the original cavity bends down and breaks through to form the larval mouth, leaving the original opening as the larval vent.

The larvae are free-swimming, and are modified from this ground-plan in five directions according to the class to which each belongs. They used to be regarded as distinct animals, and so received special names. Of the f our types of pelagic larvae of Eleutherozoa the simplest is the holothurian, of which an early stage is shown in fig. 21. The primitive mouth is surrounded at a little distance by a band of cilia, which by their vibration move the larva. A smaller ciliated band immediately round the mouth sweeps in food. The oral field, within the main band, is shaped like a broad MI; in later stages the two side portions are folded on their borders and look like a pair of human ears, whence this larva has been called cularia. The vent lies in the dle below the cross-piece of the FIG. 22.-LARVA FIXED TO SEA H, and the gut runs through the Fig. 22.-LARVA FIXED TO SEA H, and the gut runs through the FLOOR AND YOUNG STAR curved body to it, swelling on its way into a stomach but showing no twist. This larva has no skeleton, only some wheel-shaped spicules scattered through its substance. The larvae of brittle-stars and sea-urchins have a skele ton, in which long rods push out the side-folds and so increase the length of the ciliated band ; early stages are shown in fig. 21. A fancied resemblance of later stages to a painter's easel led J. Muller to called the larva Pluteus (easel). In the arrangement of the rods the Ophiopluteus differs somewhat from the Echinopluteus. The asteroid larva has no skeleton. It differs from the auricularia in the meeting of the two upper limbs of the RE, so that the oral field is like an A, and there are two complete ciliated bands (fig. 21) ; their apices are drawn out into long prae-oral lobes, and their margins are folded into narrower lobes or pinnae, whence the larva was called Bipinnaria. In the recent unstalked crinoids and some other echinoderms with large yolky eggs, the larva grows within the egg till it emerges as a barrel-shaped form with five bands of cilia like the hoops of the barrel; the primitive mouth, being unused, closes.

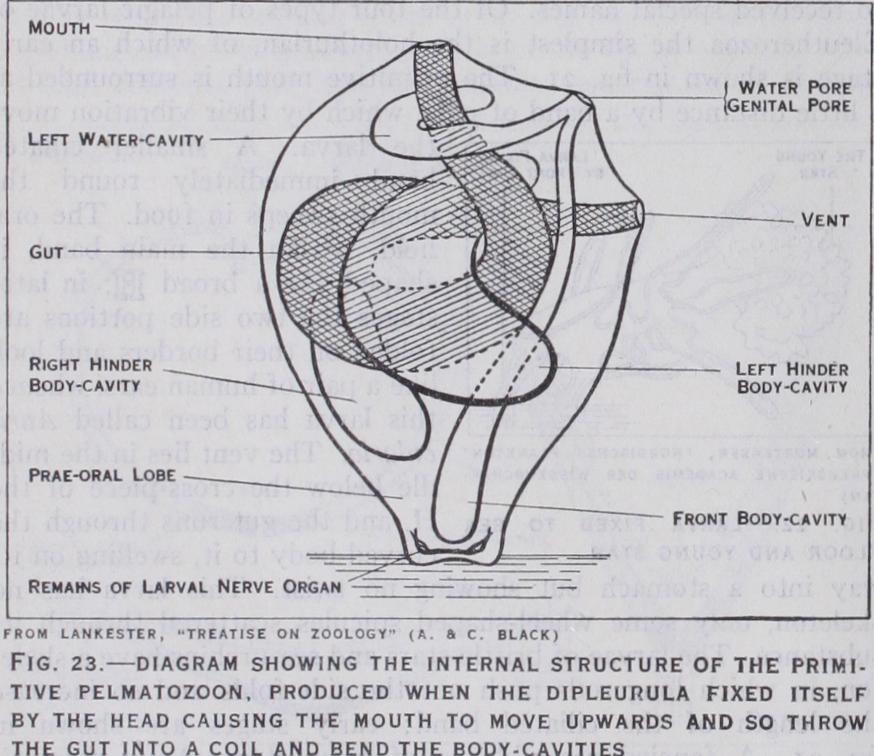

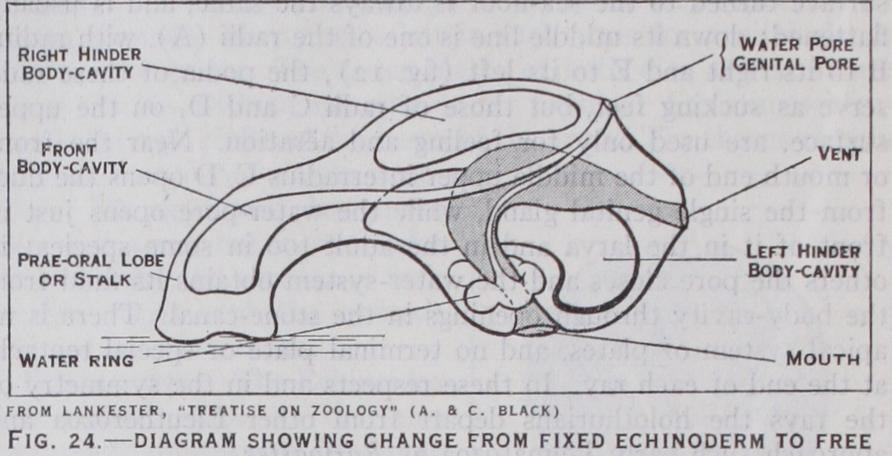

Between the larva and the adult is a series of complicated changes, during which the larval skeleton is absorbed and rede posited as the permanent skeleton, while portions of the creature are often cast aside as worn out trappings. Such a marked change is called a metamorphosis (q.v.). It is best known in some of the sea-stars, where it takes about 12 days. The larva sinks and attaches itself to the sea-floor by a portion of the prae-oral lobe (fig. 22); this is pulled out into a stalk, and the future star developed within the body of the larva. The essential change is the curving of the left hydrocoel and the left hinder coelom round the gut, till each becomes a ring. In the asteroid the oral face of the star bends downwards towards the stalk and the floor, and the water-ring closes round the stalk, which then disappears (fig. 24). In the crinoid the oral face is bent upwards, so that the water ring does not enclose the stalk (fig. 23) . As shown in fig. i 2 the water-ring closes in a different interradius with reference to the M plane in each class; this is connected with the torsions that occur during metamorphosis.

The later stages of growth are often of interest to the evolu tionist as suggesting the ancestry of the present form and the origin of its special structures. The classical instance is the rosy feather-star (Antedon bi fida) . This was thought to be an asteroid, but in 1823 J. V. Thompson, a Cork surgeon, discovered that when quite young it was fixed by a stalk like a crinoid ; the growing animal breaks away from the root, and the upper part of the stalk is condensed into a knob bearing numerous stem-tendrils or cirri. This process recapitulates the race-history traced in Jurassic fossils.

Protection of the Brood.

Free-swimming larvae probably represent an ancient stage in echinoderm history, retained in the life-history to ensure the dispersal of creatures that are slow moving or fixed in the adult. The fixed larval stage that intervenes demands food-yielding and quiet waters. When, as on ice-bound coasts or in ocean abysses, such conditions do not obtain, the eggs are furnished with yolk, and both they and the developing young remain with the mother. Brood-chambers or nurseries may be formed. The thorns of some sea-stars expand like umbrellas over the young ; in some sea-urchins the ambulacral grooves are sunk to receive the eggs ; many brittle-stars have pouches hollowed in the sides of the body between the arms; the plated holothurian, Psolus, has a nursery roofed by large plates on its back; in some other holothurians the young cling by their podia to the parent's back; the stem and root of a crinoid present a natural surface of attachment for the young.

Self-division and Regeneration.

Many echinoderms can break off portions of themselves, generally under the stimulus of danger or to get out of a difficult situation. The stem and arms of the later crinoids have special breaking-planes; the brittle-star snaps off its arms when seized and disintegrates before the dis tressed naturalist ; holothurians, when attacked, eject portions of their viscera, and to this habit the cotton-spinner owes its name. The discarded portions can be grown again ; it has even been claimed that in some cases they can themselves grow fresh bodies and become complete individuals. A sea-star (Linckia) commonly avails itself of this faculty, and one may find big arms with a small body at one end, and f our little arms growing out of it; these are known as comet-f orms. The power of regeneration is probably due to the extension of all the systems of the body into the arms, but it seems that in general a portion of the central disc must also be present. A development of this power is reproduction by spontaneous division, as practised by many sea-stars, brittle stars and holothurians ; it is indeed the usual method in the British holothurian Cucumaria lactea. Sea-stars found with groups of arms of different sizes must have divided in this way.

Echinoderms are confined to the sea, and differ in this from all but one or two branches of the Animal Kingdom. The limitation is probably connected with the density of the water, since echinoderms depend largely on their hydraulic system, and there is besides a constant interchange between the internal fluids and the outer water through the thin membranes. Any sudden change would be particularly fatal to the larval stages, which transport the species to other localities. Some species tolerate a change better than others, but few are found even in brackish water. Within the sea, however, echinoderms may occur from anywhere between tide-marks down to 6,000 metres (3-i- miles) . Those between tide-marks are generally buried in moist sand; some urchins bore holes in rock, and these retain a little water; few can stand being left high and dry. In littoral waters examples of all classes are numerous, but the greatest abundance and variety occur between i,000 and 2,000 metres; in the greater depths both species and individuals are fewer. Most species have a limited range of depth, but a few have considerable extension; thus, the brittle-star Ophiacantha bidentata ranges from 5 to 4,450 metres. No order and no family is exclusively either littoral or abyssal, but two highly modified kinds of holothurian occur only floating in the open sea.

Since the depths of the sea are connected and their conditions uniform, species inhabiting them may be found in any of the oceans. The conditions of coastal waters are varied, and so, con sequently, are the species, few having a really wide distribution; the chief exceptions are circumpolar species, which may stretch down the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Some Arctic species appear to be represented in the Antarctic by similar forms, a phenomenon also observed in other groups of marine animals. Attempts have been made to map out various regions, each characterized by its echinoderm fauna, and from these to infer past migrations and possible changes of land and sea ; but knowledge is still incom plete and opinions too diverse for summary here. Echinoderms have been said to abound more in the tropics, where certainly they are more striking in colour ; but modern dredging shows that they occur in the same enormous quantities and rich variety in polar and temperate seas. In the Atlantic brittle-stars may be brought up by hundredweights, and the "Challenger" dredged 1'0,000 unstalked crinoids at a single haul.

Geology gives only a succession of fossil forms ; the relation of these to one another is interpreted through facts of anatomy and development, and seen to be an evolution. In its main lines the race-history is now thought to have been as follows. We start with a dipleurula larva (fig. 9) , still free-floating and with none of the peculiarities of the modern adult echinoderm. The event that originated the branch was the discovery of the sea-floor, on which followed the adoption of a stationary life and the deposi tion of lime spicules in the skin. The three-rayed spicules grew into star-shaped plates loosely joined, such as are scattered in Lower and Middle Cambrian rocks. As the plates grew, they were more firmly united, and completer skeletons were preserved. These, at the outset, show a divergence. The Machaeridia (fig. Io) may represent the elongate stage before fixation. If the elongate form became fixed by the middle of its body, the mouth and the vent would be on the two sides of the base of attachment, and from such a creature all the nonradiate Carpoidea (fig. I I) may have descended. They are found only from Middle Cambrian to Devonian.

Origin of Radiate Forms.

Radiate forms had a different origin. The dipleurula, apprehending the floor by its sensory front end, fixed itself, not by the ciliated pole, but a little to one side, the right side being chosen for a reason we cannot yet fathom. The result was the passage of the mouth to the upper surface (fig. 23). As it passed up along the left side, the gut caught hold of the left water-sac and pulled it upwards, curving it in the process. Since this was attached to the left duct from the front body-cavity, that structure was also pulled up and its pore came to lie between mouth and vent, while the stretched part of the front cavity formed a canal lying along the outer wall. The gut, as it coiled, drew the left hinder coelom also upwards in a curve, while the stomach pressed the right hinder coelom down to the fixed end, where it was involved in the elongation of that region. Not only can these changes be traced in the developing Antedon today, but several of the older cystoids had the structure of such a primitive pelmatozoon. Notably they retain the pore by which the genital products, formed from the canal alongside the body wall, were extruded. At this stage no radiate structure was visi ble, but, unlike Carpoidea and Machaeridia, these forms had the fundamental plan on which the radiate types were built.Radiation arose from the mode of feeding combined with the effect of gravity. Fixed to the sea-floor, with its mouth upturned to the food-bearing waters, which it swept inwards by the cilia of the gullet, the primitive pelmatozoon extended its food-collect ing surface by the outgrowth of ciliated channels from its mouth as already described under Cystoidea. A limit was set to this increase by the size of the body itself.

Crinoids and Feather-stars.

Another class, based on a better plan, appeared first at the close of Cambrian time and by the close of Devonian time had taken the place of the cystoids; this class was the Crinoidea. Here the length of the food-grooves was increased by the actual outgrowth of the body-wall in the direction of the five rays, but upwards; the outgrowths became jointed, and repetition of the process led eventually to the long and many-branched arms of the crinoids, in which the grooves sometimes reach the combined length of a quarter of a mile. The Crinoidea early blossomed into some half-dozen orders and be came adapted to every habitat which the sea provides. A single instance may be taken from certain shore-dwellers which in Juras sic times found safety by shortening their stem while retaining the whorls of cirri; with these, when torn away by the waves, they could grasp the nearest object. Eventually the stem was fused with the lower part of the cup into a hemisphere covered with cirri. Acquiring some power of free locomotion, this type spread into the group of Comatulida (feather-stars), which today corn prises hundreds of species, divided among 98 genera (fig. 4).

Sea-stars and Brittle-stars.

Among the oldest known echi noderms is a genus of Edrioasteroidea, a class in which radia tion had affected not only the food-grooves but the hydraulic system. Though clearly Pelmatozoa, they provide a starting-point for all classes of Eleutherozoa. Most adhered by a sucking action of the flexible under-side to smooth surfaces. Through the thin skin of that side, the genital products, it is suggested, were ex truded. At that time, if at no other, the creatures were liable to be overturned, and those that could use their podia for locomo tion would have an advantage. A sea-star is little more than an overturned Edrioaster, and some even now retain the power of feeding in the pelmatozoan way. The anatomical changes in adaptation to the new mode of life have been explained under Stelliformia (fig. 24). Fossils of the crawling asteroid type are known from the top of the Cambrian, but are rare until the Upper Silurian and Lower Devonian, when some adopted a wriggling habit and a structure tending towards the ophiuroid type. Genera with arm-grooves completely closed and with all their floor-plates turned into "vertebrae" are of doubtful occurrence earlier than the Carboniferous. Ophiuroids with elaborate vertebrae of modern type appear first in the Trias.

Sea-urchins.

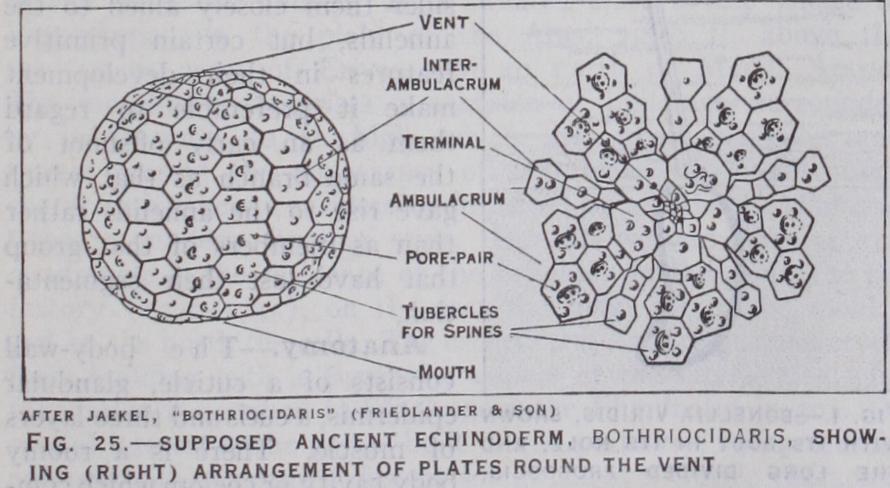

The first echinoids may also have been derived from overturned edrioasteroids ; the vent, as it passed up, was dragged a little farther back, leaving room for the madreporite, with which it became closely associated at the apical pole. The earliest known are from the top of the Ordovician. For half-a century Bothriocidaris (fig. 25), a small fossil from Esthonia, has been regarded as an ancestral echinoid, but T. Mortensen, after fresh examination, refuses to accept it. This leaves in the Ordo vician and Silurian only many-plated forms with flexible test; they cannot be derived immediately from Edrioaster since they already have well-developed jaws. The family Lepidocentridae, to which they belong, continues to the Carboniferous. Nearly all Palaeozoic echinoids have more than the 20 columns of plates found in later genera; among them the Archaeocidaridae, ap parently existing in the Devonian, are nearest the simple cidarid type, which has a solitary representative in the Carboniferous and another in the Permian. The early cidarids retained some flex ibility in the union between ambulacral and interambulacral ares; in the Triassic period this gradually gave place to a rigid union, and at the same time appeared the diademoid type, with external gills, close-set podia, and more numerous radioles. Cidaroida and Diademoida have persisted to our own day, the former relatively unchanged, the latter giving rise to successive suborders. Among these, some Jurassic genera show the beginning of that movement of the vent towards the margin which characterizes the irregular urchins. A side-branch originating in Cretaceous times was the Clypeastroida (shield-urchins) as an adaptation to life just below the sand of the shore. Another modification led to elongate urchins in which the jaws were gradually lost as the animal took to extracting nutriment from ooze. The extreme of this line is reached in the modern Spatangidae (heart-urchins).

Sea Cucumbers.

The coiled gut and radiate hydraulic system of the Holothuroidea suggest that this class also was derived from a primitive pelmatozoon. At an early stage the creature took to locomotion in the direction of the mouth, with consequent worm like lengthening of the body, possibly facilitated by the less calci fied integument. Already in Middle Cambrian shales are found the compressed imprints of soft-bodied animals with apparent holothurian structure. The closure of the food-grooves, the elab oration of mouth-tentacles, the suppression of the unused podia on the back, and the retention of the single genital gland with its pore, were all natural consequences of this mode of life. Spicules ascribed to holothurians have been found fossil from the Car boniferous onwards, but the general absence of other skeletal structures prevents one from tracing the history of the class.Echinoderms are sluggish and frequently immobile for con siderable periods. The brittle-stars are the most rapid movers. Free forms shun the light, and hide or bear a cloak of sea-weed by day. Their of ten brilliant colouring can rarely have protective value. Some sea-stars light the depths with glorious phosphor escence, and many littoral brittle-stars phosphoresce when stim ulated. This also may be a useless by-product of some activity. The general mode of life and nutrition have been mentioned under the various classes, and further details are given under STAR-FISH and SEA-URCHIN. Holothurians feed by sweeping minute creatures into the mouth with large shield-shaped tentacles, or by catching them with the slimy surface of bushy tentacles, which they push into the mouth and withdraw cleansed. Abyssal holothurians live in and feed on the ooze, breathing by the podia of the back, which are often monstrously developed. In some holothurians portions of the respiratory trees consist of slime-secreting cells; when irritated, the animal compresses its body and forces the tubes out of the vent ; the slime absorbs water and swells enormously, finally splitting into sticky threads in which an enemy can be hopelessly entangled. Many animals live in or on echinoderms as messmates: among them are protozoans, sponges, annelids, arthropods, mol luscs, and, most notably, a fish, Fierasfer, which enters the respiratory trees of holothurians. Parasites are even more numer ous. Besides the groups mentioned, they include nematodes, trematodes, a myxomycete, and the myzostomes, of uncertain affinity, found chiefly on crinoids. Many of these uninvited guests assume the livery of their host, and frequently compel structural changes.

Economic Aspects.

In the economy of Nature, echinoderms play a larger part than in that of man. The crinoids and other Pelmatozoa seem useless ; yet they have extracted from the sea millions of tons of lime and built up huge masses of rock. Derby shire marble, Belgian petit granit, the Trochiten-kalk of Germany, and many of the Oolitic freestones are largely formed of their remains. Holothurians in the sea, like earthworms on land, pass the loose detritus perpetually through their bodies, extracting the organic nutriment, and thus acting as cleansers. The same task is performed by many heart-urchins, while most of the other free moving forms, especially the sea-stars, are scavengers on a larger scale. An ocean without echinoderms might become a putrid cess pool. Unfortunately sea-stars do not confine themselves to carrion, but attack living molluscs, among them oysters and mussels, doing terrible damage (see STAR-FISH). On the other hand some of the smaller kinds are eaten by bottom-fishes, and thus help to turn Nature's waste into marketable food. For the im mediate food of man most echinoderms are unsuitable, but some holothurians are used in the East (see BECHE-DE-MER), and in various parts of the world the ovaries of the larger regular sea urchins are much appreciated. The ease with which the eggs of echinoderms can be fertilized and the early stages of development reared in the laboratory has led to their extensive use as material for research into fundamental problems of life and growth.

History.

During the 18th and first half of the 19th centuries, echinoderms were described by many eminent naturalists : Echi noidea by J. T. Klein, C. Linnaeus, N. G. Leske, E. Desor and L. Agassiz; Stelliformia by J. H. Linck; Crinoidea by J. S. Miller; Cystoidea by L. v. Buch; but it was the researches of Johannes Muller (184o-5o) that laid the foundation for a scientific treat ment of the branch. For the host of later writers on this large and varied group, reference must be made to the works cited in the bibliography.