Eclipse

ECLIPSE. One heavenly body is said to be eclipsed by an other when the second body passes between the observer and the first body so as to obscure part or all of it. Thus an eclipse (from Gr. kXa t'es, failing to appear) of the sun occurs when the moon comes between the earth and the sun. If the more remote body be completely obscured by the nearer body the eclipse is said to be total, otherwise it is termed partial. If the distant body be visible all round the nearer body at any moment the partial eclipse is then termed annular.

We shall divide the consideration of eclipses as follows: I. General considerations.

II. Eclipses of satellites of Jupiter.

III. Eclipsing binary stars.Iii. Eclipsing binary stars.

IV. The calculation and prediction of eclipses (explained in detail for eclipses of the sun) laws and cycles of eclipses of the sun and moon.

V. Phenomena of eclipses of the sun.

VI. "

" " " " moon.VII. Table of eclipses in the aoth Century.Vii. Table of eclipses in the aoth Century.

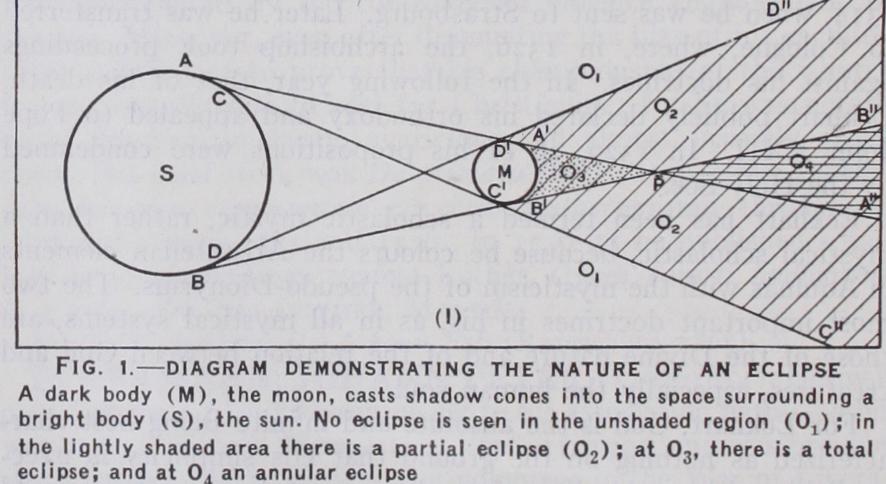

A convenient way of regarding an eclipse is to consider the shadow cast by a dark body (such as the earth or moon) into the space surrounding a bright body (such as the sun). Thus if fig. I represents a section through the centres S and M of a bright body S and a dark body M, and AA', BB' be the exterior and CC', DD' the interior common tangents respectively we see that to an observer situated, as at outside the cone formed by CC', DD', there will be no obscuration of S ; from an observer situated within the cone, as at part of S will be hidden; and if he be within the cone formed by AA', BB' and between its apex P and M, as at the whole of S is hidden from him.

If we know the sizes of S and M and their motions we can determine the form and position of the shadow cones at any mo ment, and hence can say whether any other body (e.g., the earth or a particular point on it) falls within them.

In fig. 2 if S represents the sun, M the moon and E the earth we have in (r) the configuration necessary for an eclipse of the moon, in (2) that required for an eclipse of the sun.

If all the members of the solar system revolved in orbits which were in the same plane, then there would be an eclipse at every revolution of a satellite around its primary. Thus once a month we should have an eclipse of the sun when the moon was between us and the sun (i.e., at a time of new moon) and an eclipse of the moon a fortnight later when we were between the sun and moon (i.e., at a time of full moon). The orbits are not coplanar but slightly inclined to one another, and so it can happen that the axis of the shadow cones passes above or below the more distant body and no eclipse visible on the planet may occur. We shall explain the matter in detail for eclipses of the sun, and it will be seen that the considerations advanced apply mutatis mu tandis to eclipses of the moon or other bodies. The planets be tween the earth and the sun (Venus and Mercury) clearly may pass between us and the sun. These occurrences are technically termed transits, but the calculations concerning them are essen tially the same as for eclipses.